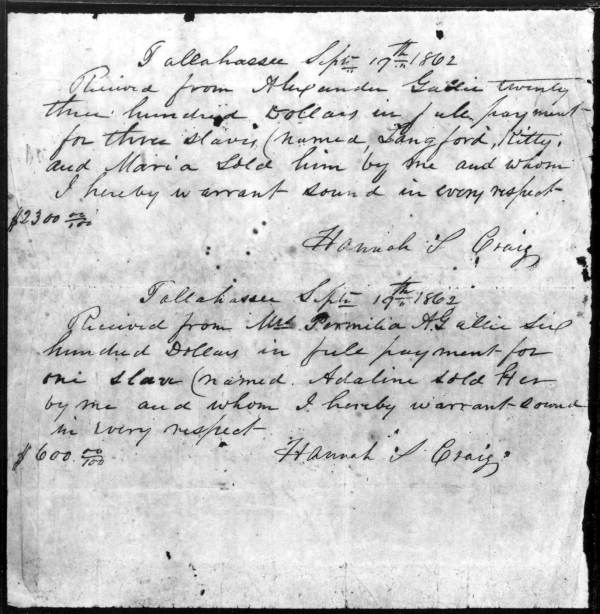

Description of previous item

Description of next item

Unheralded Emancipation (May, 1862)

Published May 5, 2012 by Florida Memory

On May 9, 1862, Union Major General David Hunter declared freedom for all slaves living in the states of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

Although his declaration was not the first emancipation measure during the war (Major General John C. Frémont had previously ordered the freeing of Rebel-owned slaves in Missouri), Hunter’s action shocked both the Confederate and Union governments.

The seceded states had long portrayed the Republican administration of Abraham Lincoln as a government of radical abolitionists. Lincoln, however, pursued a conservative approach to emancipation, which he did not officially endorse until September 1862 with the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

While he personally abhorred slavery and hoped for its eventual extinction, Lincoln argued that secession, not the existence of slavery in the South, was the reason for the war. He believed that a crusade for emancipation would lose the slave-owning Border States (Missouri, Kentucky and Maryland) to the Confederacy. This concern led him to revoke Frémont’s order and remove the general from command.

Unlike Frémont’s order, which only applied to slaves owned by persons actively supporting secession, Hunter’s order called for the liberation of all slaves, whether owned by Confederates or Unionists, within the area of his command (South Carolina, Georgia and Florida).

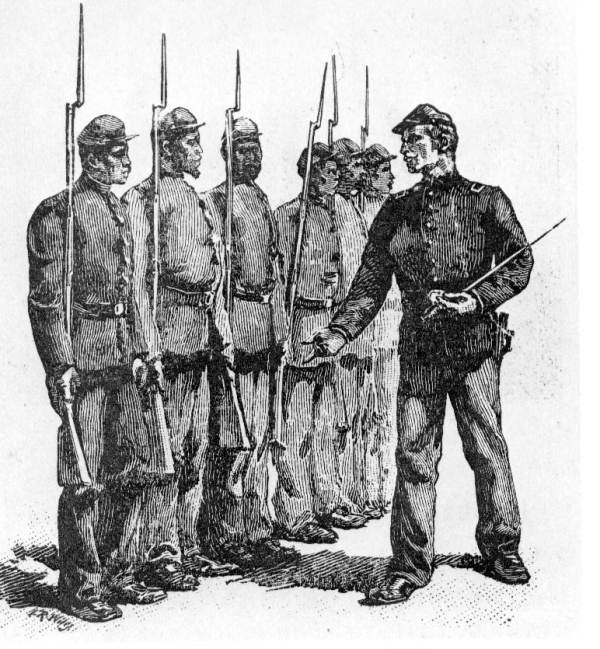

It did not differentiate between slaves actively employed in Confederate war work and those engaged in civilian labor such as agriculture, which was the previous requirement for releasing slaves under the Union’s Confiscation Act of 1861. Hunter then used his order to enlist freed slaves into the Union Army.

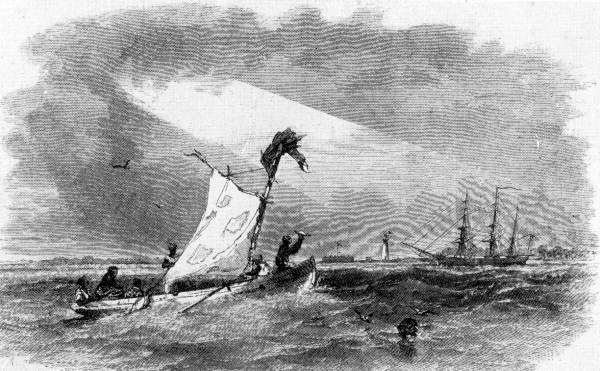

Contrabands (runaway slaves) escaping to the Unites States bark Kingfisher off the coast of Florida (1862)

Lincoln insisted that only the President as commander-in-chief could issue an emancipation order. He announced that his government had no prior knowledge of Hunter’s intent to issue such a proclamation and declared the order void.

The War Department ignored Hunter’s effort to create a black regiment. While Hunter’s policies made him popular with abolitionists, most Northerners in the spring of 1862 were not ready for emancipation or the arming of freed blacks.

The South’s view of Hunter’s policies was obviously even less enthusiastic. Emancipation and arms for blacks fed the long-held Southern fear of confronting an insurrectionary slave population.

The Confederate government viewed Hunter’s actions as a call for slave rebellion and a racial outrage. It proclaimed General Hunter an outlaw. If captured, he would not be entitled to the rights of a prisoner of war but liable for execution at the discretion of the President of the Confederate States.

Ironically, Jefferson Davis, the president who would have signed Hunter’s death warrant, had known Hunter for over 30 years; they had been friends since first meeting as young army officers in 1829.

For a complete picture of Hunter’s fascinating and controversial career—he also served as president of the military commission that tried the suspects in the Lincoln assassination conspiracy—see Edward A. Miller, Jr., The Biography of David Hunter: Lincoln’s Abolitionist General (University of South Carolina Press, 1997).

Of course the biggest potential impact of Hunter’s emancipation order and recruitment of blacks was on slaves in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Only a month before Hunter’s proclamation, several escaped slaves who had flocked to Union gunboats off of Jacksonville, which the Federals had captured in March, were forcibly returned to their Confederate masters after the Union evacuated the city in April 1862.

A year later, however, when the Union occupied Jacksonville for a third time, it was black soldiers of the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry regiments who greeted the escaped slaves. No longer unheralded, the black soldiers’ expedition filled the columns of newspapers across North and South.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Unheralded Emancipation (May, 1862)." Floridiana, 2012. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/252635.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Unheralded Emancipation (May, 1862)." Floridiana, 2012, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/252635. Accessed March 9, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2012, May 5). Unheralded Emancipation (May, 1862). Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/252635

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program