Description of previous item

Description of next item

Thomas Sidney Jesup and the Second Seminole War

Published October 10, 2012 by Florida Memory

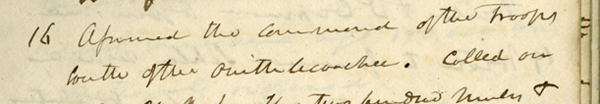

October 16, 1836

The Secretary of War ordered General Thomas Sidney Jesup to Florida in October 1836. In this entry, he acknowledged the beginning of his service in Florida. However, this was not his first experience with American Indian warfare. Prior to receiving these orders, Jesup was deployed in a military campaign against the Creek Indians in Alabama and Georgia. Tensions erupted in violence in the Creek Country as white settlers encroached upon Indian lands.

The lands in question had been guaranteed to the Creeks under the treaties of Fort Jackson (1814) and Indian Springs (1821 and 1825). The Treaty of Fort Jackson formally ended the Red Stick War (1813-1814), which began as a civil war among the Creeks. After an attack on Fort Mims, north of Mobile, Alabama, by the rebel Creeks, Andrew Jackson and militia from Tennessee joined the Creeks friendly to the United States. Jackson's entry into the war contributed to the eventual defeat of the rebel Creeks, or Red Sticks, at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Shortly thereafter, Jackson arranged a punitive treaty that resulted in the transfer of over 14 million acres of Creek land to the United States.

Two other agreements took place between the Creeks and the United States in 1821 and 1825 at Indian Springs. The Creek leader William McIntosh, also known as Tustunnugee Hutkee, and his faction received allotments of land for themselves, while at the same time ceding control of much of what remained of the Creek Country. In April 1825, Creeks who opposed the treaty killed McIntosh and others in his party for signing the agreements. Settlers and land speculators flooded into the Creek territory following the second Treaty of Indian Springs. In several instances, armed confrontations occurred between Creeks and settlers. These confrontations led to the outbreak of the Second Creek War (the Red Stick War is considered the First Creek War).

In 1836, Creeks hostile to the United States launched a series of attacks against white settlements. The state governments of Georgia and Alabama demanded protection against what they considered unwarranted Indian depredations. As a result of these pleas for assistance, Thomas Sidney Jesup arrived to subdue the rebel Creeks.

The Second Creek War ended shortly after it began. The majority of Creeks were evicted from their lands and forced to emigrate to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. Only a few families remained in the east. In the 20th century, this small band gained federal recognition as the Poarch Band of Creek Indians.

November 27, 1836

"They brought newspapers which announced that Gen. J[esup] had been ordered to take command of the Army and that an officer had been sent from Washington on the 4th with orders to that effect."

On November 27, 1836, Jesup learned of his appointment as commander of all U.S. troops operating in Florida against the Seminoles.

When he first arrived in Florida in October 1836, General Jesup assumed command of U.S. troops operating south of the Withlacoochee River. Governor Richard Keith Call commanded troops north of the Withlacoochee and presided over military operations in the territory of Florida.

Jesup arrived in Florida amidst controversy. While serving in the Second Creek War, Jesup disagreed with General Winfield Scott, his superior officer, on how to conduct the campaign against the Creeks. Jesup argued for swift action against Creek towns hostile to the United States. Frustrated by inaction on the part of Scott, Jesup went ahead without orders in hand.

In a fortunate turn of events for Jesup, his campaign worked and likely shortened the war. Scott, on the other hand, received criticism for his delay. In order to defend his reputation, Scott challenged Jesup to a review by a court of inquiry. Several months later, while Jesup was serving in Florida, the court of inquiry ruled in Jesup's favor. Jesup's bold move against the Creeks likely paved the way for his appointment as commander of military operations against the Seminoles in Florida.

December 3, 1836

"L[ieutenant] Col[onel] [David] Caulfield returned about 9 AM with forty one negro prisoners, having surprised the village, captured the greater part of its inhabitants, and burnt the houses and the property which they could not bring in."

On December 3, 1836, Lieutenant Colonel David Caulfield captured 41 black Seminoles after destroying their towns near the Ocklawaha River.

General Jesup was ordered to force the Seminoles and their African allies out of their villages in central Florida and compel them to emigrate west of the Mississippi River. He intended to achieve this by building a series of forts and supply depots surrounding the Seminole Country, and launch raids against their villages. When his troops encountered American Indian and African settlements, they were instructed to burn crops, destroy homes and round up livestock.

In this entry, Jesup reported that Lt. Col. Caulfield captured 41 "negroes" near the Ocklawaha River. Historians struggle to find an appropriate term for persons of African descent living in the Seminole Country. From the earliest beginnings of African slavery in the Americas, runaway slaves sought refuge among Native American tribes. From the mountains of Jamaica and Brazil, to the swamps of Florida, Africans formed independent communities and forged alliances with Native peoples.

In Florida, these people came to be known to the Americans as "black Seminoles" or "Seminole Maroons." Prior to the Seminole Wars, black Seminole communities could be found near Old Town on the Suwannee River, east of Tampa at Piliklakaha, and near modern day Sarasota at a settlement known as Angola. Other smaller settlements of black Seminoles existed throughout this range. After Andrew Jackson's slave raid into Spanish Florida, also known as the First Seminole War (1816-1818), some American Indian and African towns took refuge in the remote interior sections of central Florida.

In early 1836, Seminoles and their African allies launched a series of attacks on sugar plantations located along the east coast of Florida. Africans enslaved on these plantations fled during the chaos and in many cases joined black Seminole towns.

One of Jesup's primary objectives in the early stages of the Second Seminole War was to uncover and destroy black Seminole towns. From the perspective of plantation owners, the existence of free-blacks and runaway slaves among the Seminoles was the primary cause of the war. To most non-Indians, all blacks living among the Indians were slaves. They did not understand the often complex relationships between Africans and Native Americans.

The Seminoles held few Africans in bondage in the manner practiced on southern plantations. Instead, most black Seminoles played important roles as military allies and contributors to herding, hunting and planting activities. A few black Seminoles such as Abraham served as advisors and interpreters for Seminole leaders. Abraham interpreted and provided council for Micanopy, the principal leader of the Seminoles until 1837, at all of the major negotiations covered in the Jesup diary.

As with the majority of the Seminoles, the U.S. Army removed most of the black Seminoles from Florida during the Second Seminole War. Very few black Seminoles remained in Florida after the Third Seminole War (1855-1858) and by the 20th century, only a couple Seminole families traced their roots back to the black Seminoles.

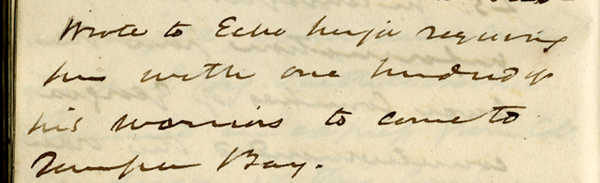

December 24, 1836

When Jesup arrived in Florida he had already formed alliances with Creek Indians in Alabama and Georgia. These Creeks were friendly to the United States, and some had been party to treaties with the Americans. When the Second Creek War broke out, Indian leaders loyal to the United States joined American troops in punitive raids against rebel Creeks; some also served in Florida against the Seminoles.

In this entry from the diary, Jesup wrote to friendly Creek leader Echo Harjo, who was already operating in Florida against the Seminoles, to request he bring 100 warriors to Tampa Bay. At this point in the campaign, Jesup was planning an incursion into the Seminole territory. The Creeks under Echo Harjo's command served as valuable guides and interpreters, as they spoke the same language as the Seminoles (Muscogee) and were familiar with the territory.

Fighting against Seminoles and their African allies was nothing new to Creeks friendly to the United States. During the First Seminole War, Creeks under the leadership of William McIntosh participated in attacks on the Negro Fort, the Suwannee Old Towns, and other villages in Florida. Nearly 800 Creeks joined American forces fighting Seminoles in Florida during the Second Seminole War.

The warriors under Echo Harjo's command did not necessarily come to Florida by choice. They were told that loyal service in Florida guaranteed the welfare of their families in Alabama and Georgia. News of the troubles stemming from the Second Creek War caused great discontent among Echo Harjo's warriors. Some defected to the Seminoles rather than continue to fight as allies with the Americans (see Jesup diary, March 11, 1837). Echo Harjo and other friendly Creek leaders reported on several occasions that they heard rumors of abuses suffered by their families. Jesup reassured them that their families would not suffer unduly from the fighting in the Creek Country.

After the conclusion of the Second Seminole War, most of the friendly Creeks returned to their homes. Despite their military service to the United States against the Seminoles, within a few years most were forced to emigrate to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

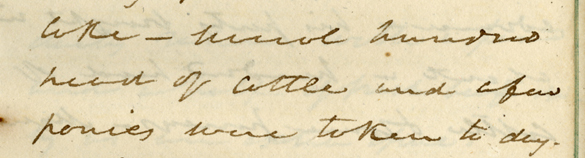

January 28, 1837

Florida Indians herded cattle long before the outbreak of the Second Seminole War. Indian (and African) cowboys tended Spanish livestock as early as the 17th century. After the destruction of Spanish Missions in northern Florida by the Creeks and white settlers from Carolina (1702-1704), Muscogee-speaking Indians migrated south into the vacant lands.

By the late 18th century, these Muscogee-speaking migrants came to be known as Seminoles. The largest of the Seminole settlements was Cuscowilla, located on the Alachua Prairie near modern day Micanopy, Florida. The naturalist William Bartram, who came to Florida in the mid-1770s, wrote that the Seminoles worked thousands of cattle on the Alachua Prairie. They sold hundreds of animals yearly to the Spanish and the British. The leader of the Alachua Seminoles during Bartram's time was appropriately known to the British as the "Cowkeeper."

After Florida became a territory of the United States in 1821, Seminoles increasingly came into conflict with white settlers over land, cattle and runaway slaves. The ill-defined boundaries between Seminole and American lands resulted in numerous instances of violence along the frontier. Whites stole Seminole cattle, and vice versa. The issue of slavery compounded the problem, as plantation owners often ventured into the Seminole Country in search of runaway slaves.

The Second Seminole War began after a series of coordinated attacks by Seminoles and their African allies in late 1835 and early 1836. The swiftness of these offensives caught the Americans off guard and required a significant change in strategy on the part of the U.S. Army. Jesup arrived in Florida to implement this plan, which included building a network of forts and supply depots and conducting raids into the heart of Seminole territory.

Seizing cattle and burning crops formed the basis of undercutting the Seminoles' ability to sustain their war effort. In this entry, Jesup reports the capture of "several hundred" head of Seminole cattle near the Withlacoochee River. Jesup regularly reported that his men rounded up hundreds of animals (cattle and horses) at a time. Nearly every week of the diary includes references to the depletion of Seminole herds.

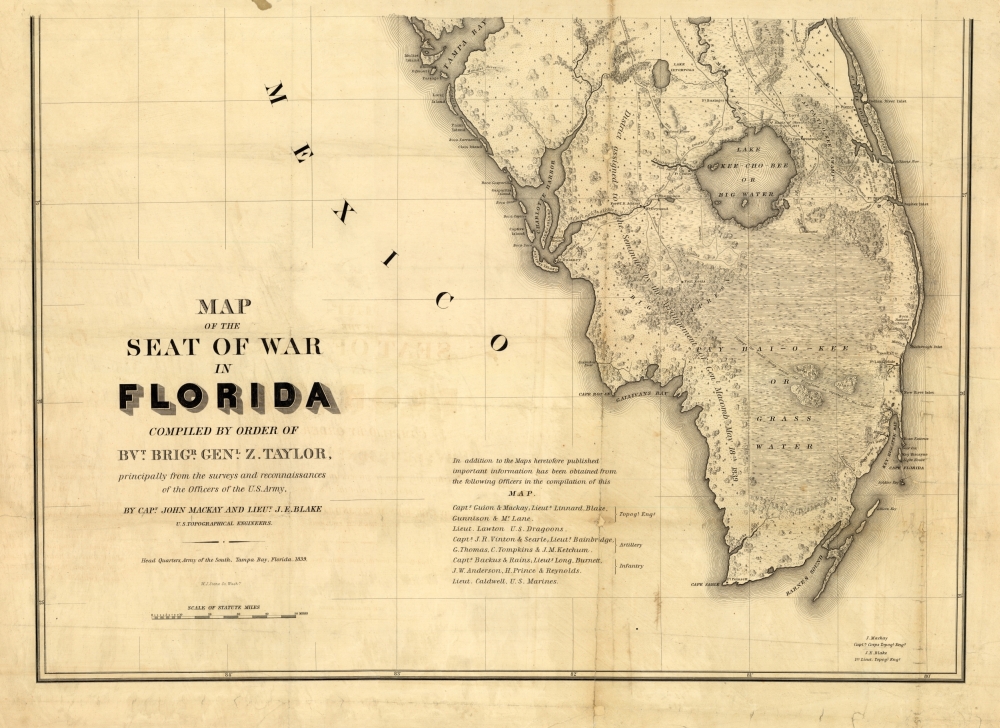

Excerpt from "A Map of the Seat of War in Florida," by Captain John Mackay and Lieutenant J. Blake, U.S. Topographical Engineers (1839)

During negotiations with Jesup, Seminole leaders insisted that they be allowed to drive their animals west as a condition of their agreement to emigrate. Jesup refused and instead offered compensation for livestock left behind in Florida (see Jesup diary, March 5-6, 1837). Through the efforts of the U.S. Army, Seminole cattle were reduced to near zero by the end of the Seminole Wars in 1858. Federal Indian agents in the early 20th century counted only a handful of oxen owned by Seminole camps.

It was not until federal programs in the 1930s and 1940s that cattle again became a mainstay of Seminole life. Today, the Seminole Tribe is one of the largest cattle owners in the state of Florida.

February 3, 1837

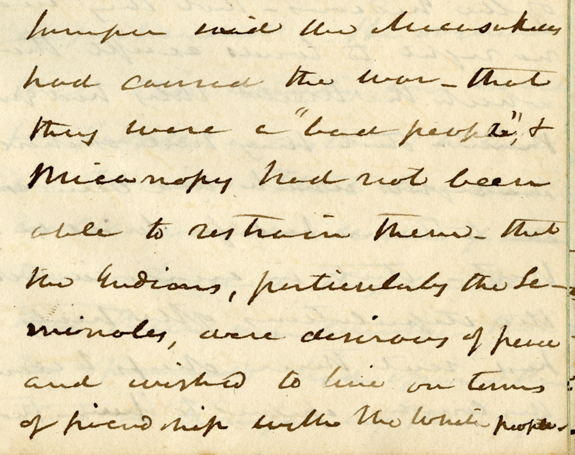

"Jumper said the Miccosukees had caused the war—that they were a "bad people" & Micanopy had not been able to restrain them—that the Indians, particularly the Seminoles, were desirous of peace and wished to live on terms of friendship with the white people."

Native Americans living in Florida during the Seminole Wars were not, in fact, all Seminoles. However, from the perspective of the United States government, all Florida Indians were Seminoles. It was more expedient to deal with Native peoples inhabiting a particular region as if they were a single entity, with one set of political views, rather than recognize their diversity. This practice was foundational to the Indian policy of the United States in the early 19th century; all Indians in Alabama and Georgia were Creeks, and all Indians in Florida were Seminoles.

The reality was that the Creeks and Seminoles were not one political entity unto themselves; nor did they always act independently without joint council. The conflicts between the so-called "friendly" and "rebel" Red Stick Creeks were only one of several ways Creeks (and Seminoles) divided themselves. They considered themselves first as a member of a clan, second as a resident of a town, and third, part of a larger collection of towns that comprised a confederacy. Scholars disagree over which—clan, town, or nation—was most important in influencing the identity and daily life of southeastern American Indians.

When Jesup arrived in Florida he quickly learned that a great difference of opinions existed among the Seminoles on the issue of removal. Because of his experience in the Second Creek War, he was already aware that not all Creeks considered themselves part of a single political entity. In this way, military officers on the ground often differed from policy makers far removed from the theater of war; Jesup learned to respect the internal divisions in Indian society even if his superior officers remained ignorant of the same.

In this entry from his field diary, Jesup reports that Jumper, also known as Otee Emathlar, echoed the sentiments of other Seminoles that the Miccosukees (also spelled Mikasuki and several other ways) had started the war. Jesup had previously heard this statement from the black Seminole Abraham, interpreter and adviser for Micanopy (see Jesup diary, January 31, 1837).

The Miccosukees migrated to Florida in the early 18th century. They spoke a dialect of the Muscogee language known as Hitchiti, which although related to was mutually unintelligible from the main Muscogee tongue. Their early date of arrival in Florida from the north made the Miccosukees the first Native American immigrants into the territory after the destruction of the Spanish Missions in 1702-1704.

According to Seminole leaders who met with Jesup, the Miccosukees refused to negotiate and intended to remain hostile to the United States. The division between Seminoles and Miccosukees is not as clear-cut as it may seem, and these were certainly not the only factions of Florida Indians involved in the war. Jesup also became aware of Creeks, Red Sticks, Tallahassees and Uchees (also spelled Yuchi or Euchee) involved in the fighting. With the exception of the Creeks friendly to the United States, most Florida Indians resisted removal.

Another factor that complicates Jumper's statement is his intent. Jesup believed that Seminole leaders were delaying removal by blaming the war on the Miccosukees. It would have been impossible for Jesup to tell a Miccosukee from a Seminole unless they declared themselves to him. Assigning blame to the Miccosukees for causing the war might have been a tactic designed to frustrate and stall the Americans. While the negotiations dragged on, the Seminoles continued to receive federal rations. Since most of their livestock were driven off and their fields burned by the U.S. Army, the government-supplied rations were necessary for survival.

Evidence from the period after the end of the Seminole Wars in 1858 may support Jumper's claim about divisions between Seminoles and Miccosukees. In the 20th century, the federal government became aware that Florida Indians considered themselves to be at least two distinct groups. Seminoles lived in the Kissimmee River Valley north of Lake Okeechobee and spoke Creek (or Muscogee), Miccosukees lived in the Big Cypress Swamp and near the Miami River and spoke Hitchiti (or Mikasuki).

The movement to federal reservations, which began in the 1930s, further highlighted these differences. In the 1950s and 1960s, internal political divisions led to the creation of two federally recognized tribes in southern Florida: the Seminole Tribe of Florida, and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida. Some Florida Indians refused to join either of these Tribes, and remain independent to the present day.

March 18, 1837

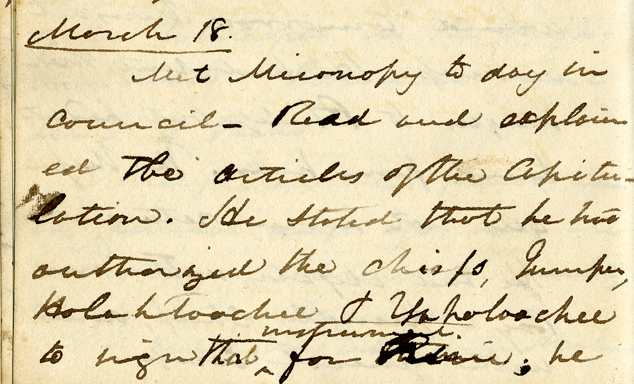

"Met Micanopy to day in council—Read and explained the articles of the Capitulation. He stated that he had authorized the chiefs, Jumper, Holahtoochee & Yaholoachee to sign that instrument for him, he…"

"…agreed to every article, and formally ratified it. He, Aligator, and John Hopony a friendly chief, dined with Gen[era]l J[esup]. Had a talk with Aligator after dinner in relation to the movement of his people to Tampa & thence west."

On March 18, 1837, Micanopy agreed to the articles of capitulation negotiated by Jumper, Holatoochee, and Cloud.

After the initial military successes by the Seminoles in December 1835 and early 1836, the United States Army responded with search and destroy-style tactics in order to undermine the Seminole resistance.

As noted in this entry, by March of 1837 several Seminole leaders had begun negotiations with General Jesup to end the war. Prior to the meeting of March 18, Micanopy's advisor and interpreter, the Black Seminole Abraham, met with Jesup on several occasions to outline the leader's position. Micanopy belonged to a line of hereditary leaders among the Alachua Seminoles. It appears that he was likely related to King Payne and the Cowkeeper, previous leaders of the Alachua Seminoles, through his mother's family.

Like other southeastern Indians, Seminoles traced descent through the mother's line. Anthropologists refer to this form of social organization as matrilineal. Hereditary leaders did not have absolute power. Their words probably carried more weight than any other single individual, but they ruled by persuasion rather than coercion. Other individuals such as war leaders, religious leaders, and advisors like the black Seminole Abraham also influenced decisions that impacted the Seminoles as a whole. Micanopy's power, therefore, was somewhat more limited than Jesup likely understood. In reality, his authority extended probably no further than the boundaries of his own home village and its constituent parts.

During times of war the power structure changed. For all intents and purposes, Micanopy became the principal leader of certain bands of Seminoles during the Second Seminole War. Jesup considered his word binding on the Seminoles as a whole, even if the dispersed bands themselves thought otherwise.

The Articles of Capitulation agreed to by Micanopy on March 18 related to previous treaties between the Seminoles and the United States. When Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, one of the primary concerns of the new government was what to do with Seminoles who occupied prime agricultural lands desired by planters. In 1823, several Seminole leaders agreed to the Treaty of Moultrie Creek. This treaty, among other things, created a large reservation in central Florida, provided rations and assistance for relocation therein, and required the Seminoles to prevent fugitive slaves from residing among them.

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek was supposed to be in effect for 20 years, at which time another agreement would be drafted. However, problems resulted from the treaty almost immediately. Since not all Seminoles were present at or party to the treaty, some refused to abide by its terms. The ill-defined boundaries of the Seminole reservation invited trespassing by whites seeking escaped slaves and cattle, and likewise, Seminoles in search of game and trade ventured beyond the bounds set at Moultrie Creek.

In 1830, the United States Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. This act required all Indians living east of the Mississippi River to emigrate to the Indian Territory. Each tribe had to arrange its own eventual departure with an Indian agent assigned by the U.S. government. In 1832, Indian Agent Wiley Thompson and a group of Seminole leaders agreed to what is known as the Treaty of Payne's Landing. Before the treaty could take effect, a delegation of Seminoles would travel to the lands assigned to them in the west and thereby determine if they met the needs of the tribe.

What happened next is steeped in controversy and strikes to the very heart of the dishonorable history of U.S. Indian policy. The delegation did in fact visit the lands in question, at which point they were forced to sign another agreement, known as the Treaty of Fort Gibson. The Seminole people were informed that the delegation had already agreed to the terms of Payne's Landing and that emigration would commence in 1835. This caused outrage among the various political factions of Florida Indians.

It became immediately apparent that the vast majority of Florida Indians had no intention of leaving the territory. Many were determined to fight to protect their lands. Several Seminoles emerged at this point and became nationally known figures. Perhaps the most famous was the warrior known as Osceola. Osceola was so enraged with what took place at Fort Gibson that he engaged in a verbal altercation with the Indian agent Wiley Thompson.

For his verbal threats towards the Indian agent, Thompson placed Osceola in chains. After being released Osceola vowed to avenge this humiliation. His anger set the stage for the beginning of the Second Seminole War. In late December 1835, Osceola attacked and killed Wiley Thompson near Fort King. He also led an assault against Charley Emathla the previous month, a member of the delegation to Fort Gibson. At about the same time as Thompson died at the hands of Osceola and his band, another group of warriors routed a column of troops under command of Major Francis Dade as they traveled north from Fort Brooke on the Fort King Road.

The Seminoles and their African allies then conducted a series of raids on plantations along the east coast in the first half of 1836. It was in the context of the early successes of the Seminoles that General Thomas Sidney Jesup was sent to Florida in October 1836.

Jesup's strategy appeared to be working from his perspective. He thought the agreement reached with Micanopy on March 18, 1837, would finally end the war. Micanopy and other leaders had agreed to cease fighting. Many brought their people in to Fort Brooke and assembled for emigration. Despite these positive signs, as it turned out, Jesup was wrong.

The situation took a dramatic turn on the evening of June 2, 1837. Warriors led by Osceola and Sam Jones (Abieka) liberated several hundred Seminoles detained near Fort Brooke. This event convinced Jesup of the need for more brutal tactics against the Seminoles. He raised additional troops and again penetrated the interior of the peninsula in search of their camps. It was during this time that Jesup devised a strategy for ending the war that ended up defining the rest of his military career.

Under the commonly accepted rules of war, discussions taking place under a white flag of truce carried the expectation that all parties were free to leave. Jesup began using the white flag of truce to lure Indian leaders into talks from which he never intended their escape. Most infamously, Jesup captured Osceola using this tactic in October 1837. The famed warrior later died at Fort Moultrie in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. Instantly, the press seized on the dubious circumstances of his apprehension, and held Jesup responsible. This tarnished an otherwise lengthy career in the U.S. military for the Army's longest-serving Quartermaster.

Always at the forefront of Seminole-American negotiations was the status of Seminole property in the event of forced resettlement in the west. The issue of cattle was not easily solved, as the Seminoles depended on livestock for their livelihood.

Even more contentious was the issue of the Black Seminoles. Leaders such as Micanopy made it clear to Jesup that emigration was only possible if the Black Seminoles accompanied them to the west. Jesup had hoped to make this concession as a means towards ending the war, but met stiff resistance from southern planters and politicians. His opposition claimed that many of the blacks in Florida were seized during the war, and therefore, belonged to white plantation owners and not the Seminoles. The Seminoles maintained that this was not the case, and feared that their African allies would be taken immediately upon arriving in either Tampa, or New Orleans (the point of entry into the Mississippi River for the trek to the Indian Territory). These fears played out in the aftermath of the Battle of Loxahatchee in January 1838, when slave catchers re-enslaved many Black Seminoles despite previous agreements.

Another layer of drama resulted from the fact that the negotiations over the issue of the Black Seminoles had always involved African interpreters, such as Abraham and John Horse. Since Abraham helped council Micanopy and conduct the business of negotiating with the Americans, it can be assumed he did everything in his power to ensure a favorable outcome for the Black Seminoles.

Any conclusions Jesup felt had been reached by the March meetings quickly proved short-lived after the raid on Fort Brooke on the night of June 2, 1837, and in the ensuing five years of conflict.

Jesup left Florida in 1838. The mood of many Americans had turned against the General following the dubious capture of Osceola under a white flag of truce in October 1837. Northern politicians and abolitionists were especially critical of Jesup, particularly vocal opponents of Indian Removal. The time had long passed since Native Americans dominated the New England frontier, and northern politicians did not sympathize with their Southern counterparts.

Abolitionists, on the other hand, based their objections on the existence of slavery in the Southern states. They saw the Seminole Wars as more of a slave rebellion than anything else. Based on statements made early in the war, Jesup tended to agree. Abolitionists argued that if slavery did not exist there would be no runaway slaves, and hence, no Seminole Wars. Perhaps the best known abolitionist tract on the Seminole Wars is Joshua R. Giddings, The Exiles of Florida (1858).

Zachary Taylor assumed command of U.S. troops in Florida following Jesup's departure. He was the next in line of a succession of officers that attempted to bring about a conclusion to the war, but it was not until 1842 that the conflict came to an end. Unlike other wars in U.S. history, there was neither a decisive battle, nor a detailed treaty that ended the Seminole Wars. The U.S. Army simply decided to stop pursuing the enemy. Most Seminoles had relocated to the deep recesses of the Everglades, and the troops lost the desire and the political backing to follow. By 1842, the government estimated that no more than 500 Seminoles remained in Florida.

Jesup would have welcomed the end of the war. Shortly after being relieved of his command in Florida, Jesup lobbied on behalf of the Seminoles to allow them to remain in South Florida. He concluded that the war did little good opening up new lands for settlement, as the area south of Lake Okeechobee was considered nothing more than an expansive, malarial swamp. The aftermath of the battles of Okeechobee and Loxahatchee had significantly reduced the number of Black Seminoles in Florida and thereafter escaped slaves ceased to be the primary concern of the U.S. Army.

However, tensions between the Americans and the Seminoles did not end in 1842. Another war nearly broke out in the late 1840s and, in 1855, a surveying team destroyed property at Billy Bowlegs' camp in the Big Cypress Swamp. Bowlegs retaliated and thereafter began the Third Seminole War, which lasted until 1858. The war ended when Bowlegs agreed to surrender and emigrate with his people to the Indian Country west of the Mississippi River. When the steamboat Grey Cloud embarked from Tampa on May 8, 1858, it marked the last forced removal of Seminoles from Florida.

In the early 1880s, government officials attempted the first census of the Seminoles since the end of the third war. Two different enumerators found 208 and 296 Seminoles in Florida, respectively. It is likely that others, understandably suspicious of the government, hid from the census takers. In any case, the Seminole population in Florida had been reduced from approximately 5,000 to less than 300 as a result of forced removal and warfare.

The Seminole population recovered over the next several decades. They developed innovative means of adjusting to the new environmental realities of life in South Florida. The animal hide trade of the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought relative prosperity to Seminole families. For example, through the acquisition of sewing machines during the hide trade, Seminoles created the vivid patchwork clothing styles now synonymous with their culture. Patchwork designs are just one example of the new traditions invented by Florida Indians following the trauma of the Seminole Wars.

Life was certainly not easy for the Seminoles who remained in South Florida. The collapse of the hide trade impoverished Seminole communities from the 1920s until the emergence of income from casino gaming in the 1980s. The few bright spots for the Seminoles during their years of want were federally funded cattle, education, and health programs.

The present-day association of Seminoles with casino gaming has obscured the long and difficult history experienced by these people. The story told in this series on the Jesup's field diary is certainly one of the darkest chapters in Seminole history. Nevertheless, the diary and the larger context in which it was produced have much to tell us about the changing nature of Anglo-American Indian-African relations, and the important place of the Seminole Wars in United States history.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Thomas Sidney Jesup and the Second Seminole War." Floridiana, 2012. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/255861.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Thomas Sidney Jesup and the Second Seminole War." Floridiana, 2012, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/255861. Accessed February 13, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2012, October 10). Thomas Sidney Jesup and the Second Seminole War. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/255861

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

![They brought newspapers which announced that Gen. J[esup] had been ordered to take command of the Army and that an officer had been sent from Washington on the 4th with orders to that effect. They brought newspapers which announced that Gen. J[esup] had been ordered to take command of the Army and that an officer had been sent from Washington on the 4th with orders to that effect.](/fmp/learn/floridiana/images/tsjnov271.jpg)

![_tsjdec3p1 L[ieutenant] Col[onel] [David] Caulfield returned about 9 AM with forty one negro prisoners, having surprised the village, captured the greater part of its inhabitants, and burnt the houses and the property which they could not bring in.](/fmp/learn/floridiana/images/tsjdec3p1.jpg)

![_tsjdec3p2 L[ieutenant] Col[onel] [David] Caulfield returned about 9 AM with forty one negro prisoners, having surprised the village, captured the greater part of its inhabitants, and burnt the houses and the property which they could not bring in.](/fmp/learn/floridiana/images/tsjdec3p2.jpg)

![…agreed to every article, and formally ratified it. He, Aligator, and John Hopony a friendly chief, dined with Gen[era]l J[esup]. Had a talk with Aligator after dinner in relation to the movement of his people to Tampa & thence west. …agreed to every article, and formally ratified it. He, Aligator, and John Hopony a friendly chief, dined with Gen[era]l J[esup]. Had a talk with Aligator after dinner in relation to the movement of his people to Tampa & thence west.](/fmp/learn/floridiana/images/tsjmarch18p21.jpg)