Description of previous item

Description of next item

The Tri-State Defense of the Apalachicola River

Published November 11, 2012 by Florida Memory

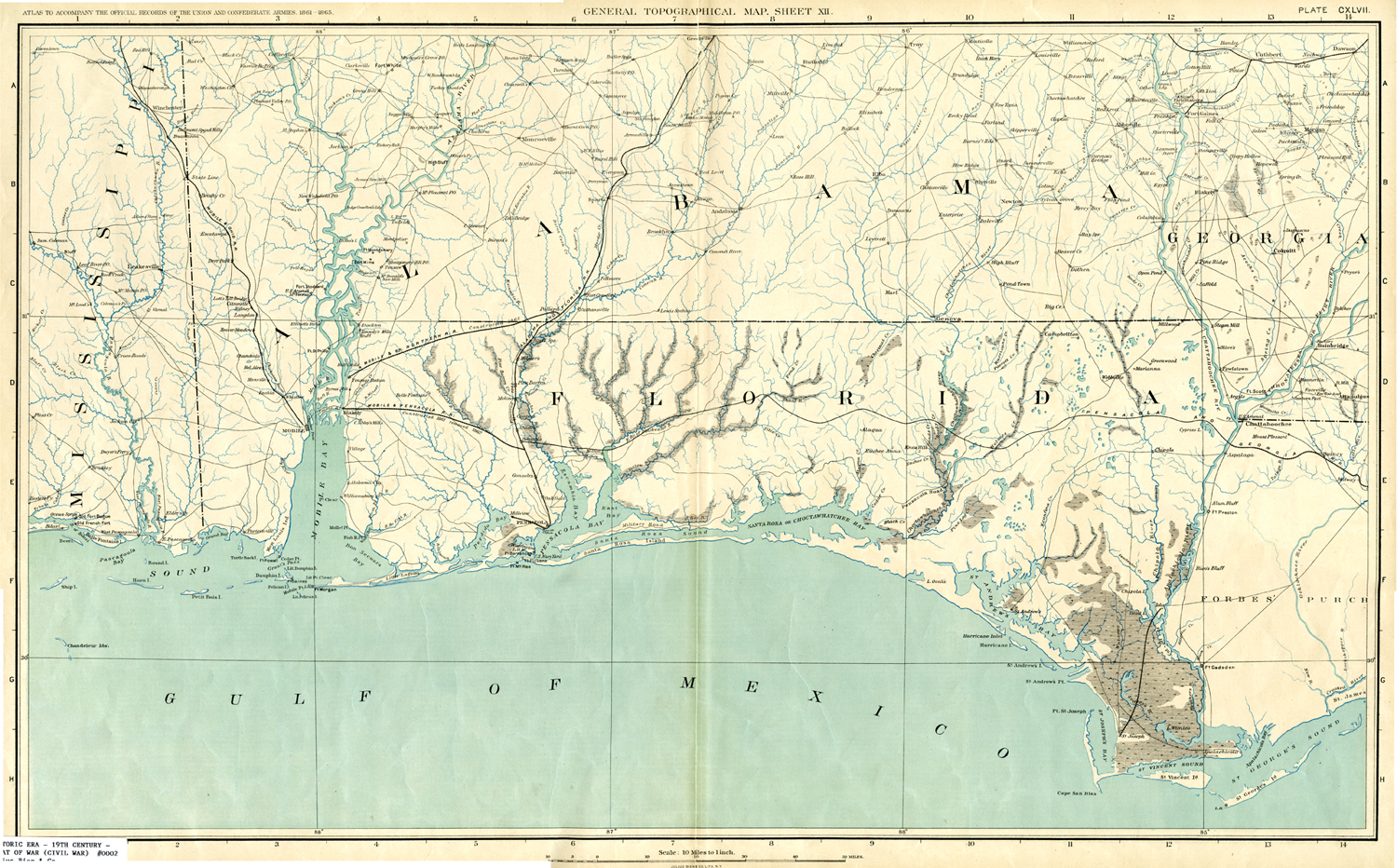

Historians have long pointed to lack of cooperation between state governors and the central government in Richmond as one of the principal reasons for the defeat of the Confederacy. Added to that problem was contention between many of the governors about how best to wage the war. Since bad news sells better than good news, instances of cooperation between Confederate governors or between the governors and Richmond are less well known. One such episode occurred in Florida in November 1862, when the Confederate government agreed to support the creation of a new military department to strengthen the defense of the tri-state region bordered by Alabama, Florida and Georgia.

Florida Governor John Milton conceived the idea of the tri-state military district. In doing so, Milton acted on his long-held belief that the Apalachicola River was the most promising avenue for a Union invasion of Florida. He feared that Union capture of the port of Apalachicola and an advance up the river would allow the Yankees to capture and destroy the rich cotton fields of Gadsden and Jackson counties—Jackson was also Milton's home county—before proceeding to the tri-state border, where the Apalachicola meets the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers flowing down from Georgia and Alabama, respectively. Union forces could then push on to Columbus, Georgia, the Chattahoochee's most important port and one of the Confederacy's few industrial centers. Milton hoped that a tri-state military department providing for the defense of portions of West and Middle Florida, southeast Alabama, and southwest Georgia would enable him to call on the bordering states for troops to help defend Florida, where only a small number of Confederate troops remained after the spring of 1862.

Milton first proposed the tri-state defense department in a letter to Jefferson Davis as early as October 29, 1861, barely more than three weeks after becoming governor. At the same time, he wrote to Governor Joseph E. Brown of Georgia and Governor A. B. Moore of Alabama requesting their support for the idea. At that time, his fellow governors were not enthusiastic—they did not see the need for such a department—and Davis passed on Milton's proposal to the Confederate War Department, which ignored Milton's request. A year later, however, Brown and Alabama's governor John Gill Shorter were more receptive. They realized that with Florida's denuded defenses their states were more vulnerable to attack from the south. In addition, both states had invested heavily in salt production along Florida's Gulf Coast. Thousands of Georgians and Alabamians were producing salt in Florida and their citizens, along with the rest of the Confederacy, depended on the vital supply of salt from Milton's state.

In October 1862, Milton again asked President Davis to support the tri-state department. This time he agreed. Davis may have changed his mind due to Milton's loyal support for the unpopular conscription law, which Davis had pushed the Confederate Congress to pass in April 1862. Assured of Davis' backing, Milton, Brown and Shorter submitted a formal request for the creation of the department to Davis on November 11, 1862. The governors' proposal placed the following counties within the department: Henry, Dale, Barbour, Russell, Covington, Coffee, and Pike in Alabama; Decatur, Thomas, Miller, Early, Baker, Clay, Calhoun, Randolph, Quitman, Stewart, Muscogee, Chattahoochee, Mitchell, and Dougherty in Georgia; and Leon, Gadsden, Wakulla, Jefferson, Madison, Liberty, Washington, Jackson, Calhoun, and Franklin in Florida.

Despite Davis' initial support, Milton again ran into difficulties with the Confederate War Department. They did, however, split the Department of Middle and East Florida into two districts: the District of Middle Florida, covering the area between the Choctawhatchee and Suwannee rivers; and the District of East Florida, which consisted of the rest of Florida east of the Suwannee River. Milton also failed to get Richmond's approval to incorporate the Alabama counties into the new defensive arrangement. The Confederate army's adjutant and inspector general, General Samuel Cooper, informed Milton that since the Alabama counties fell outside the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, those counties could not be part of the new Florida district. Fortunately for Milton, Cooper agreed that the Georgia counties could be under the new District of Middle Florida. Milton had finally gotten Richmond to take notice of the Apalachicola region, even though Florida would remain at the bottom of the Confederate government's defensive priorities.

For information on relations between Florida and its neighboring states during the war see Ridgeway Boyd Murphree, "Rebel Sovereigns: The Civil War Leadership of Governors John Milton of Florida and Joseph E. Brown of Georgia, 1861-1865" (Phd. dissertation, Florida State University, 2006).

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Tri-State Defense of the Apalachicola River." Floridiana, 2012. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257289.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Tri-State Defense of the Apalachicola River." Floridiana, 2012, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257289. Accessed March 9, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2012, November 11). The Tri-State Defense of the Apalachicola River. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257289

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program