Florida Memory is administered by the Florida Department of State, Division of Library and Information Services, Bureau of Archives and Records Management. The digitized records on Florida Memory come from the collections of the State Archives of Florida and the special collections of the State Library of Florida.

State Archives of Florida

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- State Archives Online Catalog

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- ArchivesFlorida.com

State Library of Florida

Related Sites

Description of previous item

Description of next item

Lower Court

Date

Box

Folder

Transcript

1852

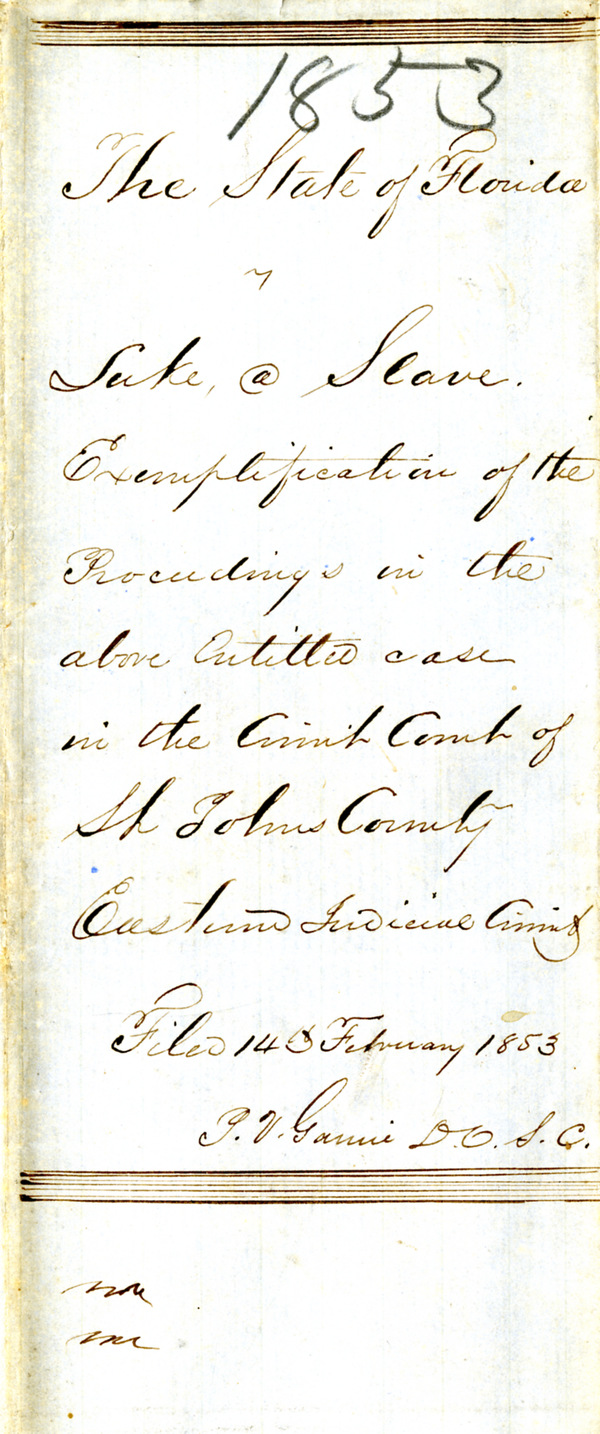

The State of Florida

Vs.

Luke @ Slave

Exemplification of the

Proceedings in the

Above Entitled case

In Circuit Court of

St. Johns County

Eastern Judicial Circuit

Filed 14[th] February 1853

Y.V. Ganui D.O.S.C

Title

Subject

Description

In 1853, the Florida Supreme Court considered the case of Luke, a slave v. State of Florida. Luke stood accused of committing a crime at the behest of his master, Abraham Dupont. Following his master's orders, Luke killed mules belonging to Joseph M. Hernandez, a Florida militia commander during the Second Seminole War (1835-42). The animals, according to Dupont, had ravaged crops on his land. Adam, a slave and head driver for Hernandez, discovered the mules dead along the road that connected the two plantations with St. Augustine; he traced the source of the deed to Luke.

The Circuit Court of St. Johns County had, in 1851, found Luke guilty of "malicious destruction of property" under Florida's penal code of 1832. Another issue of note from this case was that Dupont had allowed Luke to carry a firearm, as evidenced by his shooting of the mules. Florida law was unclear about this point. In practice, masters strictly prohibited slaves from keeping firearms, except in cases such as Luke's where the weapon had a specific purpose.

Luke's lawyer, McQueen McIntosh, challenged the Circuit Court decision on the grounds that slaves were not afforded protection under the penal code as revised in 1832. The 1832 law outlined separate punishments for blacks and whites who committed the same offense. The debate then turned to whether the 1832 law adequately covered the questions raised by the crimes committed by Luke, or if he should be tried under an earlier law of 1828, specifically, in accordance with the slave codes reserved for bondsmen. In essence, the case boiled down to whether or not Luke was capable of exerting free will, or if he had to kill the mules because he was ordered to do so by his master? If he had no choice in the matter, should his master instead be charged with the crime?

These questions proved too complex for the court to fully consider and the case was vacated on procedural grounds. The judge found that in order to perpetuate the institution of slavery and the superiority of whites over blacks, Luke could not be charged under the 1832 law. The case also brought forward issues involved with the interpretation of the 1828 slave codes, but the court declined to engage the myriad problems arising from the 1828 and 1832 laws as they related to slaves.

This case demonstrated the powerlessness of the enslaved in the antebellum legal system in Florida. As made clear in the case of Luke, white jurists would rather forgive his crimes than allow a slave to stand trial on equal footing with white men.

The Luke decision helped establish precedent for other cases involving slavery in Florida before the Civil War, including Clem Murray, plaintiff in error, v. State (1860).

Creator

Source

Date

Format

Language

Type

Identifier

Coverage

Folder

Box

Lower Court

Total Images

Image Path

Image Path - Large

Transcript Path

Thumbnail

Chicago Manual of Style

Florida Supreme Court. State v. Luke, a Slave. 1853. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. <https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/260659>, accessed 24 February 2026.

MLA

Florida Supreme Court. State v. Luke, a Slave. 1853. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. Accessed 24 Feb. 2026.<https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/260659>

AP Style Photo Citation

(State Archives of Florida/Florida Supreme Court)

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program