Description of previous item

Description of next item

Florida and the Civil War (September 1863)

Published September 9, 2013 by Florida Memory

Lost Victory: The Battle of Chickamauga and the Floridians Who Fought There

The Battle of Chickamauga (September 19-20, 1863) was the last major Confederate victory of the Civil War. It was also one of the bloodiest: the Confederates suffered 18,000 casualties and the Federals 16,000. The battle was the second largest battle of the war, only Gettysburg was larger.

Chickamauga was also important for Florida. All six of Florida’s regiments in the war’s western theater (the territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River) were engaged in the battle. As a result of their fighting at Chickamauga, General Braxton Bragg, commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, created the “Florida Brigade of the West” by combining the Florida regiments into one formation.

Bragg’s victory at Chickamauga was surprising. During the month leading up to the battle, the Union Army of the Cumberland, under Major General William S. Rosecrans, outmaneuvered the Army of Tennessee, threatening the Confederates’ supply lines in a series of outflanking movements. Bragg was forced to evacuate Chattanooga, Tennessee, perhaps the most important railroad hub of the war, and retreat out of the state into northwest Georgia. Demoralized by this retreat, the Army of Tennessee was also plagued by internal dissension among its top commanders, most of whom despised Bragg and wanted him replaced.

Despite a long and significant military career, which included service in Florida during the Second Seminole War and as commander of the Confederate forces at Pensacola during the first year of the Civil War, Bragg was easy to dislike. He was a draconian disciplinarian who was quick to order corporal punishment or even the firing squad for slackers and deserters. And his handling of the Army of Tennessee resulted in a failed campaign in Kentucky in 1862 and now the loss of Tennessee. Bragg was not alone in responsibility for these failures, however. His corps commanders were notorious for disobeying his orders and one of them, Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk, was an incompetent commander but also General Bragg’s most persistent and disruptive critic. Given this state of affairs, it is amazing that Chickamauga turned out to be Bragg’s and the Confederacy’s greatest victory in the west.

The Battle of Chickamauga is named for Chickamauga Creek, a meandering tributary of the Tennessee River and the southeastern boundary of the battle, which occurred between the creek and Missionary Ridge to the northwest. After his retreat from Chattanooga, Bragg reorganized and reinforced his army behind the Chickamauga in preparation for a counteroffensive against Rosecrans’ three corps, which were pushing into Georgia along three separate roads each running through mountain passes. The principal sources of Bragg’s reinforcements came by rail from Virginia and Mississippi. Confederate president Jefferson Davis ordered General Robert E. Lee to dispatch Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s corps from Virginia to Georgia, and Bragg received a portion of General Joseph E. Johnston’s army from Mississippi.

Included in the Mississippi reinforcements were three Florida infantry regiments: the 1st, 3rd, and 4th. In addition, after consolidating Confederate forces from East Tennessee into his army, Bragg gained several more regiments, including the 1st Florida Cavalry, Dismounted, and the 6th and 7th Florida infantry regiments. During the Battle of Chickamauga, the Florida regiments formed two brigades under the respective commands of Brigadier General Marcellus Stovall (1st, 3rd, and 4th) and Colonel Robert C. Trigg (1st cavalry Dismounted, 6th and 7th). Trigg’s brigade joined the units of Longstreet’s corps, which formed the left wing of Bragg’s battle plan, while Stovall’s men were attached to the right wing under Bragg’s nemesis, General Polk.

The battle began on the morning of September 19, when Union forces met advanced units of Polk’s wing, which along with the rest of the Army of Tennessee was moving across the Chickamauga hoping to catch the Union forces off guard. As Polk’s men engaged the Federals during the morning, Longstreet’s corps moved into position on the left and launched attacks against the Union center and right.

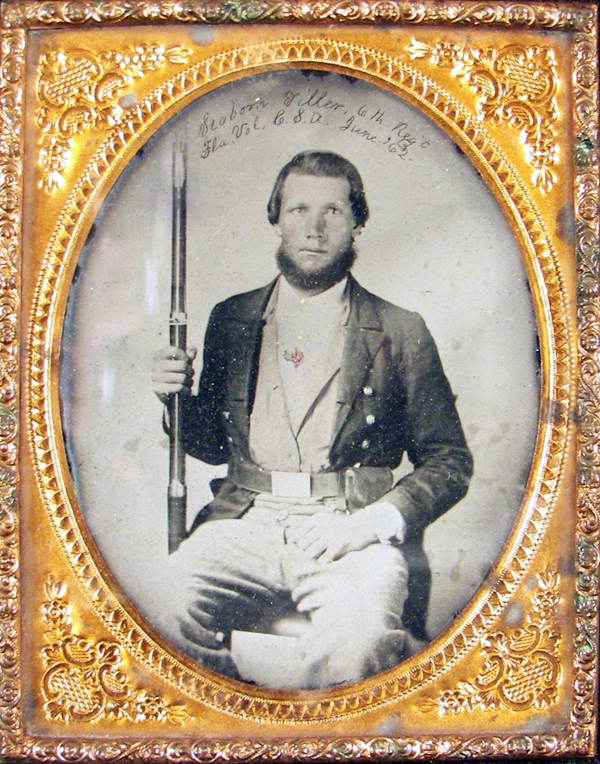

Trigg’s brigade was one of the leading Confederate units in the assault on the Union right, which got underway by the afternoon. The 1st Florida Cavalry was the first Florida regiment to come under Federal fire. Federal mounted infantry dismounted to pepper the horseless Florida cavalrymen with rife fire which was eventually compounded by Union artillery barrages. The 1st Florida Cavalry retreated from this barrage, moving back to reform with the rest of the brigade. Meanwhile the 6th and 7th regiments attacked Union positions at Viniard Farm and, like the 1st’s cavalrymen, came under withering Federal artillery fire. The 6th was the most exposed regiment and experienced the worst of Trigg’s brigades fighting on the 19th. By the end of the day, the Union lines remained unbroken and Bragg’s army regrouped to attack on the following day. The Florida units had performed well, but the toll had been high, especially for the 6th Florida, which ended the day with 35 killed and 130 wounded.

Bragg’s army had much more luck on the 20th, but not at first. General Polk was supposed to attack the Union left during the early morning, but he dithered and did not launch the assault for several hours. Before noon, however, Longstreet’s wing took advantage of an unsupported movement by one of Rosecrans’ divisions which opened up a gap in the Union line. Longstreet’s men poured through the gap, causing panic in the Union center and right.

As those sectors of the Union line collapsed, the Confederates, including the Florida brigades, pressed the attack on the Union left, where troops under General George H. Thomas defended a series of small hills known as Horseshoe Ridge. Thomas’ men withstood repeated Confederate assaults and managed to hold out long enough for the Army of the Cumberland to avoid total defeat as it retreated to Chattanooga, which Bragg’s army soon besieged. Once again, it was the 6th Florida which sustained the most casualties among the Florida regiments as it tried to break the Union line along Horseshoe Ridge.

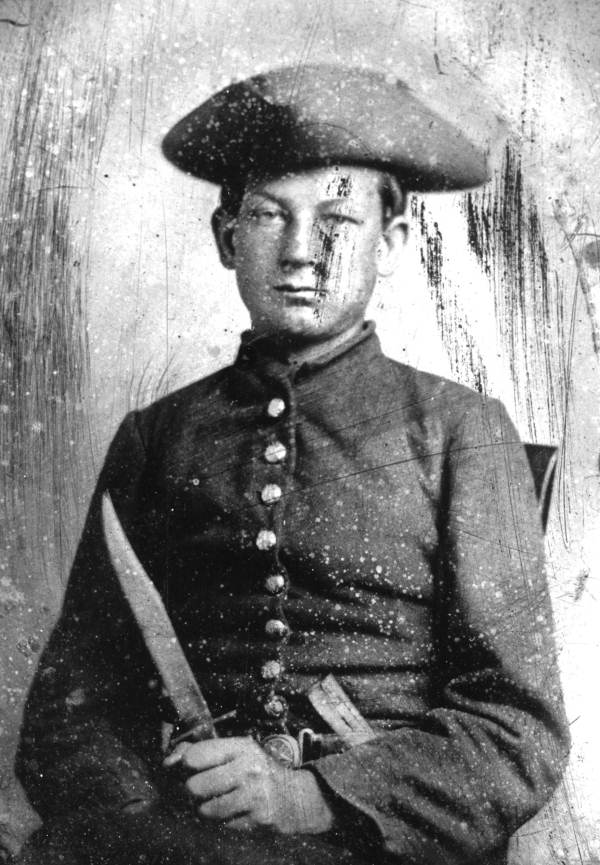

At the end of the battle on the evening of the 20th, Washington M. Ives Jr., a young soldier in the 4th Florida, observed a portion of the appalling butcher’s bill that was Chickamauga: “During Sunday night the 20th inst I walked and rode nearly all over the bloody battle field of Chickamauga. Hundreds of dead lay on the ground, bloody and ghastly, most with faces upward and some with the arms sticking up as if reaching for something . . . .”

After the battle, the Army of Tennessee was also reaching for “something,” the recapture of Chattanooga, but failed to achieve it. Instead of destroying the Army of the Cumberland, within two months, Bragg’s army would endure its most devastating defeat and lose all of the gains that it had won at Chickamauga.

Washington Ives’ letters to his family are available for research in the manuscript collection of the State Library of Florida, where you will also find a copy of the history of the “Florida Brigade of the West”: Jonathan C. Sheppard, By the Noble Daring of Her Sons: The Florida Brigade of the Army of Tennessee (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2012).

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Florida and the Civil War (September 1863)." Floridiana, 2013. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295126.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Florida and the Civil War (September 1863)." Floridiana, 2013, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295126. Accessed March 9, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2013, September 9). Florida and the Civil War (September 1863). Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295126

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program