Description of previous item

Description of next item

Butler Beach and Jim Crow

Published May 5, 2014 by Florida Memory

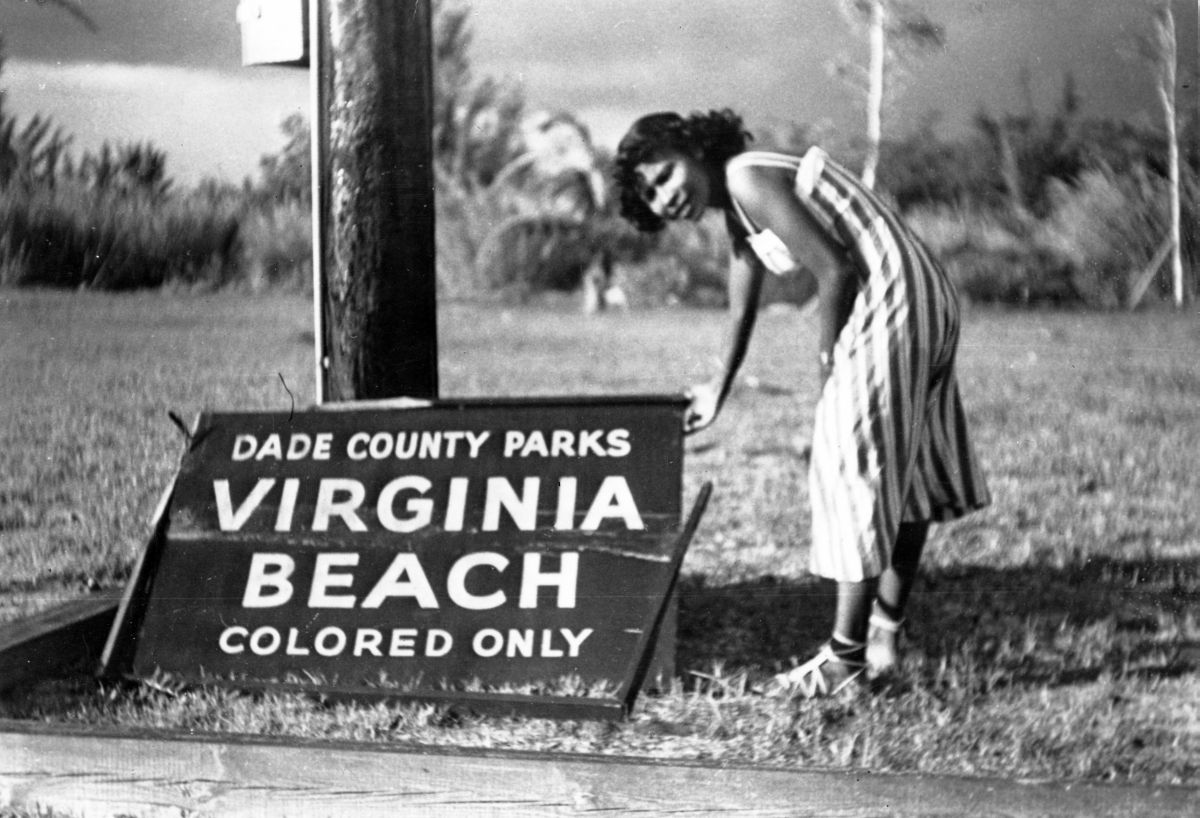

Millions of visitors and locals alike enjoy Florida’s beaches every year, along with the public facilities built to enhance them. That privilege was restricted for many years, however, by Jim Crow laws that prohibited African-Americans from sharing those beaches with their fellow citizens who were white. In some areas, public authorities provided separate beaches designated for use by African-Americans, such as Miami’s Virginia Beach, shown below.

A woman stands by the sign for Virginia Beach in Miami, which was designated for African-American use only. The sign had been blown down in a recent storm (1950).

Elsewhere, private individuals took the initiative. African-American businessman Frank B. Butler responded to beach segregation in northeast Florida by purchasing and opening his own beach on Anastasia Island.

An interior view of the Palace Market in the predominantly African-American Lincolnville district of St. Augustine. Owner Frank B. Butler stands at right (circa 1930s).

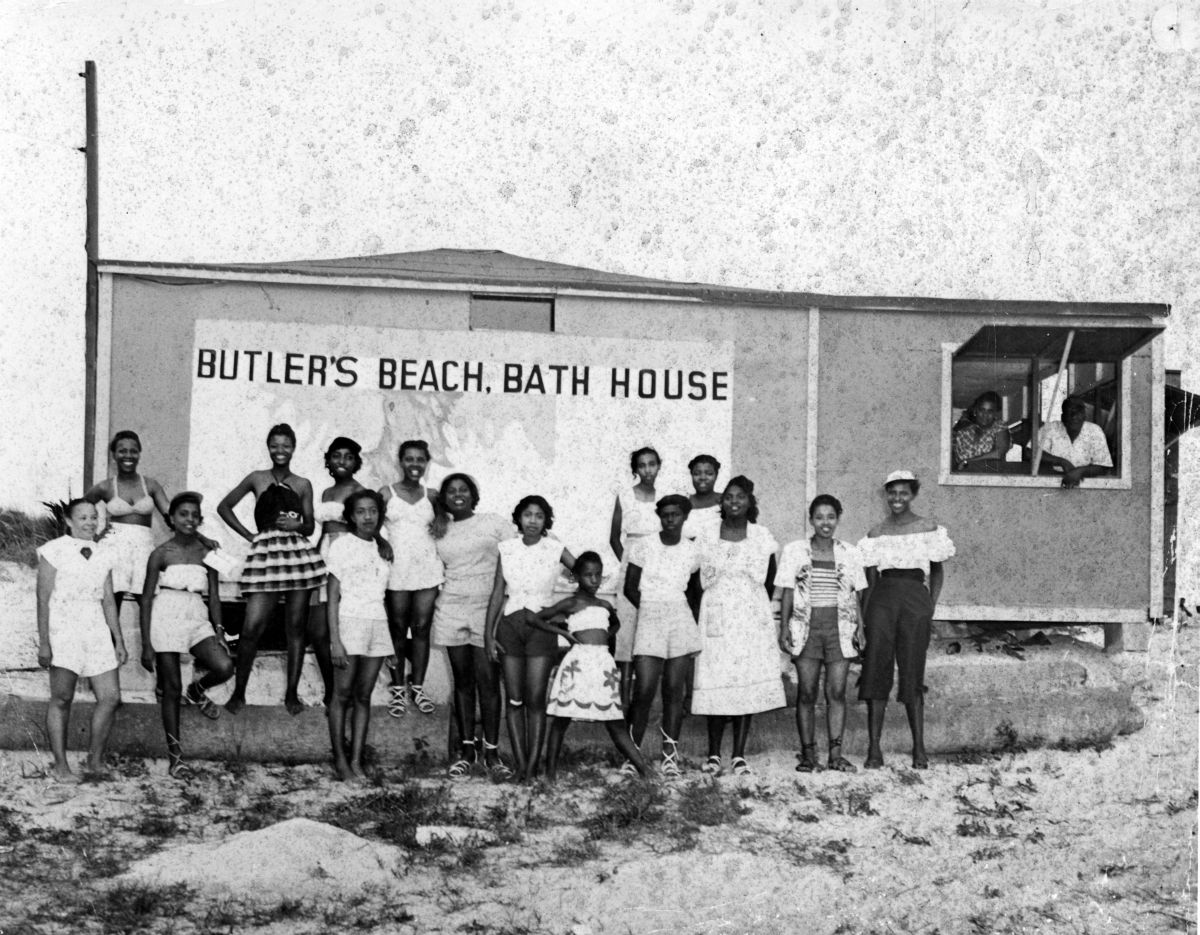

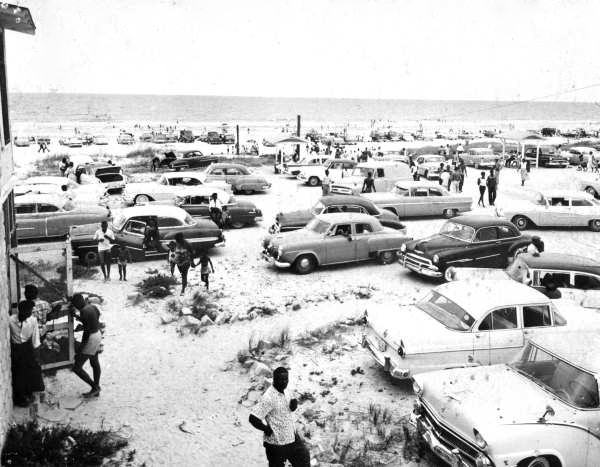

Butler, who owned the Palace Market in the Lincolnville district of St. Augustine, began buying land on Anastasia Island in 1927. Over time, he developed a residential subdivision, casino, motel, and beach resort for African-Americans. By 1948, at least eleven African-American-owned businesses operated in the area, and “Butler Beach” was a thriving tourist attraction. This was reputedly the only beach between Jacksonville and Daytona that African-Americans were allowed to use. These photos depict Butler Beach at the height of its popularity in the 1950s.

Cars pack the parking area at Butler Beach, as visitors enjoy a sunny day on Florida’s Atlantic coast (circa 1950s).

Later, Butler Beach was operated by the Florida Park Service. Eventually, St. Johns County took over the park, which it still operates today for the enjoyment of all citizens (circa 1960s).

Teachers, you may find our Black History Month resource guide to be helpful when planning for lessons about civil rights, Jim Crow segregation, or other aspects of the African-American experience in the United States.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Butler Beach and Jim Crow." Floridiana, 2014. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295168.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Butler Beach and Jim Crow." Floridiana, 2014, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295168. Accessed March 10, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2014, May 5). Butler Beach and Jim Crow. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295168

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program