Description of previous item

Description of next item

Bone Dry: The Road to Prohibition in Florida

Published July 7, 2014 by Florida Memory

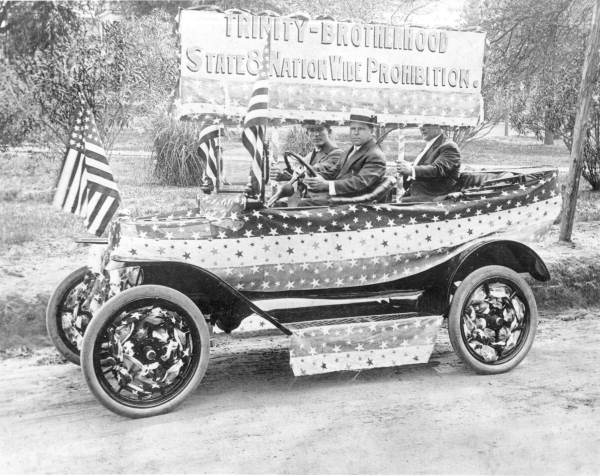

Most folks are aware of the United States’ “noble experiment” with prohibiting the manufacture and sale of liquor, which lasted from the passage of the Volstead Act in 1919 until it was repealed in 1933. Some Floridians may or may not, however, be aware that Florida had quite the head start on national prohibition, and even managed to elect a governor on the Prohibition Party ticket in 1916.

The question of whether and how to regulate or prohibit the sale of strong drink had been brewing in the individual states long before Congress dealt with the matter. In Florida, as in many states, the issue was hotly contested. Advocates of prohibition, or the “drys,” argued that liquor production and consumption was destructive to society and ought to be outlawed for the sake of health and the integrity of the family. Those who opposed prohibition, known as “wets,” countered that the government had no business interfering so deeply into the personal lives of citizens. Breweries and liquor distilleries added that to outlaw strong drink would destroy the jobs they provided to their workers.

The solution in Florida, for a time, was to provide each county with the option of whether to allow the sale or manufacture of liquor. A number of counties did become “dry” by vote of the local citizens, and they assured the rest of the state they were quite satisfied with the results. A.G. Campbell, the mayor of DeFuniak Springs, wrote in 1907 that he was sure that the crime rate in his town was very favorable to that of any wet town of the same size. W.B. Thomas, mayor of Gainesville reached much the same conclusion that year, noting that the total value of taxable property in the city was at least twice what it had been before the county went dry.

As time moved forward, prohibition became more political. The nationwide Anti-Saloon League began reporting on the progress of individual states toward prohibition, taking note of which politicians did or did not favor ending the sale and production of liquor. Carry Nation, the infamous anti-saloon activist who gained notoriety for smashing up bars with her hatchet, toured the Sunshine State in 1908 promoting a statewide prohibition law. She also endorsed Governor Napoleon Broward, who shared her views on spirituous drink and was up for reelection that year.

Carry Nation’s notoriety and reputation as a force for prohibition was remembered long after she died in 1911. Pictured here are women at a Casa Loma hotel tea social in honor of Carry Nation’s memory, in Coral Gables, Florida (February 20, 1925).

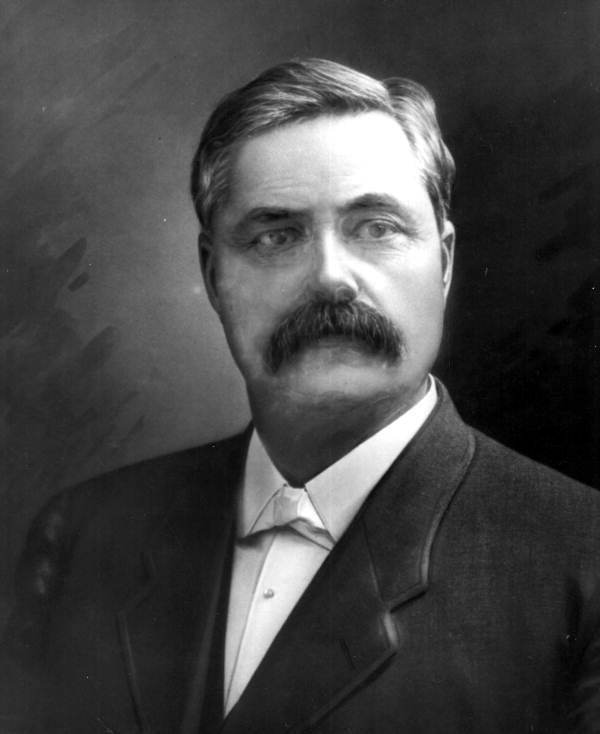

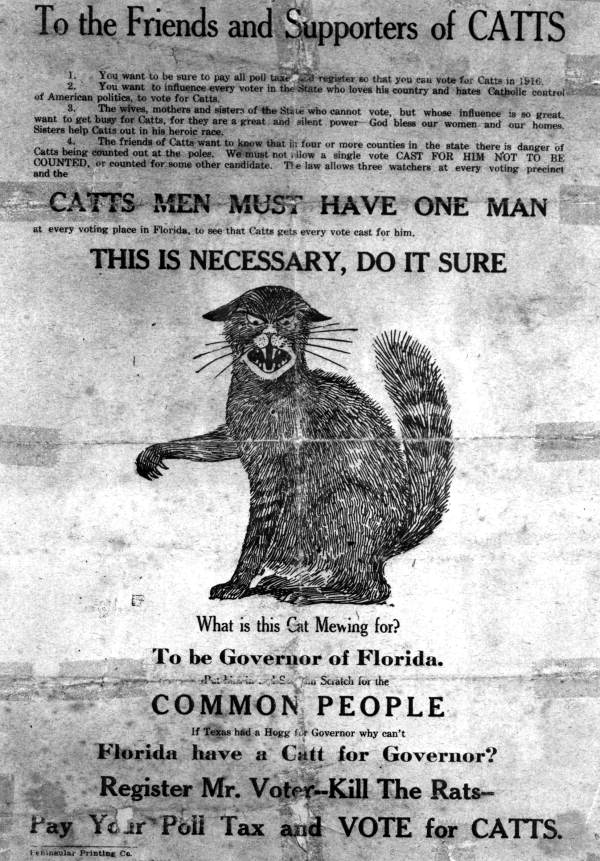

In 1916, the movement for statewide prohibition received an unexpected boost. The Democratic Party in Florida had several candidates vying for the party’s nomination for governor that year. One was William V. Knott, at the time serving as the state’s comptroller and enjoying considerable political popularity. Another was Sidney J. Catts, a Baptist minister from DeFuniak Springs who had dabbled a bit in politics as well, but seemed to have little chance of being nominated. Knott chose to conduct a very limited campaign, emphasizing the press of state business in the comptroller’s office and relying on his friends to make the speeches. Catts, on the other hand, took to the roads in his Model T Ford to reach into the most remote corners of the state, denouncing Catholicism, regulation of the shellfish industry, and the “liquor interests.”

Catts took the Democratic Party establishment by surprise when he was declared the winner of the Democratic nomination following the primary in June 1916. The margin between him and Knott was small, however, and Knott demanded a recount. The Florida Supreme Court granted the recount, and the results flipped the vote in favor of Knott by a mere twenty-one votes. Catts and a large number of his followers denounced the recount as a theft of the nomination from the people’s choice, and Catts agreed to run for governor on the Prohibition Party ticket.

Whatever the voters’ beliefs on prohibition, no third party had come anywhere close to defeating the Democrats in Florida since Reconstruction. Catts renewed his campaign efforts, however, and on Election Day in November 1916 he came away with the victory as governor of Florida. Sidney Catts would be the only non-Democrat to win the governorship between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and the election of Republican Claude Kirk, Jr. in 1966.

By this time, the number of counties having voted to prohibit the sale and manufacture of liquor had increased, but statewide prohibition was still on the table. Bolstered in part by Catts’ encouragement and also by the nationwide movement toward prohibition, the issue was finally approved by the state legislature in 1917, ratified by the voters in 1918, and put into effect in 1919. The legislature also approved the 18th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the sale and manufacture of liquor nationwide. Although Florida would be the setting for many violations of the prohibition law during its short lifetime, the Sunshine State would mostly be, as the saying goes, dry as a bone.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Bone Dry: The Road to Prohibition in Florida." Floridiana, 2014. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295191.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Bone Dry: The Road to Prohibition in Florida." Floridiana, 2014, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295191. Accessed February 13, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2014, July 7). Bone Dry: The Road to Prohibition in Florida. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295191

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program