Description of previous item

Description of next item

Somebody Give That Cow a Bath!

Published September 9, 2014 by Florida Memory

Why in the world would someone want to bathe a cow? Better yet, why would someone bathe an entire herd of cows? They’re just going to get dirty again anyway. Yet for a number of years in the early 20th century, it was very common for cattle ranchers to lead their cattle, one by one, through a vat designed to douse them from top to bottom. The practice was called cattle dipping, and it had little to do with keeping the cows clean.

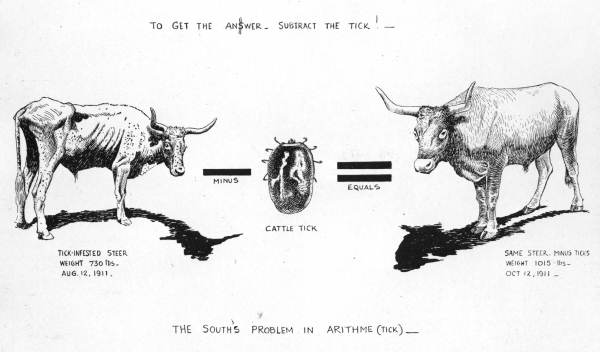

Cattle dipping was a major part of an all-out battle to eradicate Texas tick fever from Florida’s otherwise prosperous cattle industry. The fever, actually a blood infection caused by parasites, was spread through ticks, which presented a big problem for Florida ranchers, who still largely practiced the free-range system for cattle production. Rather than sticking to one fenced pasture, a rancher’s cattle might roam at will over miles of territory until their owner rounded them up. Branding kept the cattle from different ranches separate in cases where multiple herds mixed together. Under the circumstances, the cattle were bound to pick up ticks as they moved about in the woods, and there just wasn’t much to be done about it.

But they had to try. Texas tick fever was becoming a major drain on the industry’s profitability. Some farmers attempted to control tick infestations by keeping cattle and other farm animals out of a pasture for several months if an infected animal had grazed there. The idea was that if the infectious ticks had nothing to feed on for a long enough period of time, they would die and the fever vector would be gone.

Counties heavily involved in the cattle industry sometimes set up checkpoints to inspect animals for ticks before allowing them to pass, hoping to stop the spread of the fever-causing bugs. These methods had limited success. Ticks preyed on a variety of animals, both wild and domestic, so measures affecting only some animals would not protect healthy cattle from being bitten.

Early on, a few farmers experimented with the idea of washing their cattle in some sort of chemical to discourage ticks from biting them. At first, ranchers considered it a far-fetched idea, but it proved effective with a little trial and error. Over time, an arsenic solution was adopted as the most efficient agent for protecting the cattle. So long as the solution was mixed correctly and the cattle did not stay in it too long, the cow would be safe, but any ticks attempting to bite it would be poisoned.

Cow making its way through a dipping vat in Duval County, while a man marks it to show it had been dipped (circa 1920s).

Cattle dipping appeared to be a viable solution for preventing Texas tick fever, except it was difficult to get every rancher in Florida to do it. Setting up the dipping vats was expensive, and rounding up free-range cattle to be dipped every few weeks was time-consuming. Many Florida ranchers at this time had small operations, and barely had the time and help to round up the cattle a few times a year, let alone every time they would require dipping. The tick fever threat was serious, however, and eventually the state stepped in.

The Legislature passed a law in 1923 requiring every cattleman in the state to comply with a full tick eradication program, which included dipping cattle every two weeks. The new law met with mixed reactions from the state’s cattle ranchers. Some believed the state’s actions would help save the industry, while others dismissed the entire affair as needless meddling. To make the cattle dipping requirement less onerous, the State Livestock Sanitary Board contracted with private companies to build dipping vats all across the state, so that even owners of smaller cattle concerns would not have as far to travel to dip their cows.

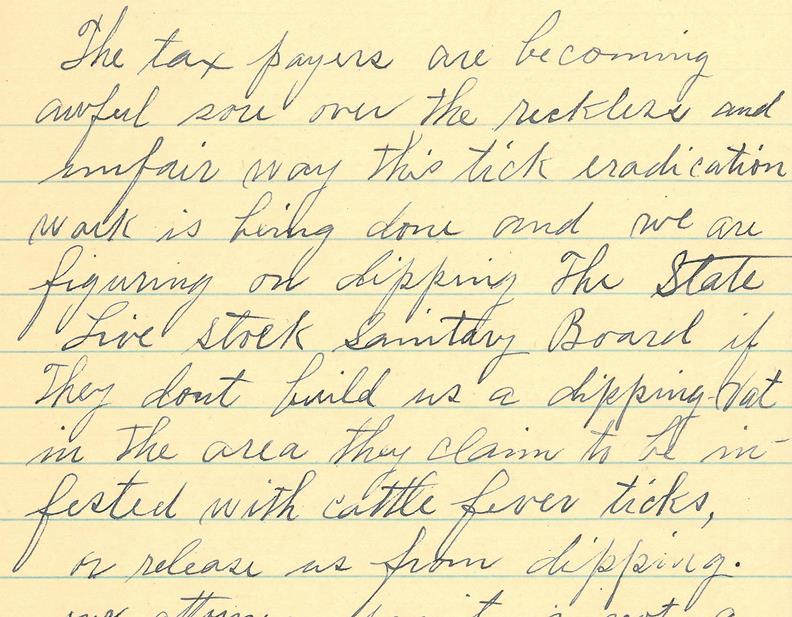

Dipping was still a chore, of course, and the records of the Livestock Sanitary Board at the State Archives are full of letters complaining about the inefficiency of the system at times. By the mid-1930s, however, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that conditions had improved enough that most areas could be released from quarantine.

Excerpt from a letter to State Veterinarian J.V. Knapp from High Springs farmer C.S. Douglass, dated Jan. 29, 1933. Douglass writes: “The tax payers are becoming awful sore over the reckless and unfair way this tick eradication work is being done and we are figuring on dipping the State Live Stock Sanitary Board if they don’t build us a dipping vat in the area they claim to be infested with cattle fever ticks, or release us from dipping” (State Livestock Sanitary Board Tick Eradication files [Series 1888], Box 2, folder 3 – State Archives of Florida).

Cattle and other stock farming is still a major Florida industry. Tell us about your experiences with raising cattle or other livestock when you share this article on Facebook or Twitter.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Somebody Give That Cow a Bath!." Floridiana, 2014. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295217.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Somebody Give That Cow a Bath!." Floridiana, 2014, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295217. Accessed February 13, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2014, September 9). Somebody Give That Cow a Bath!. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295217

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program