Description of previous item

Description of next item

When Florida Touched the Mississippi

Published September 9, 2015 by Florida Memory

The calm, winding Perdido River currently serves as Florida’s western boundary, but that hasn’t always been the case. In fact, for much of the 18th and early 19th centuries, Florida’s territory extended all the way to the Mississippi River!

The story of how the humble Perdido ended up as Florida’s western edge is a complex but important one. Today’s blog uses maps from the State Library of Florida to explain how this boundary shifted over time.

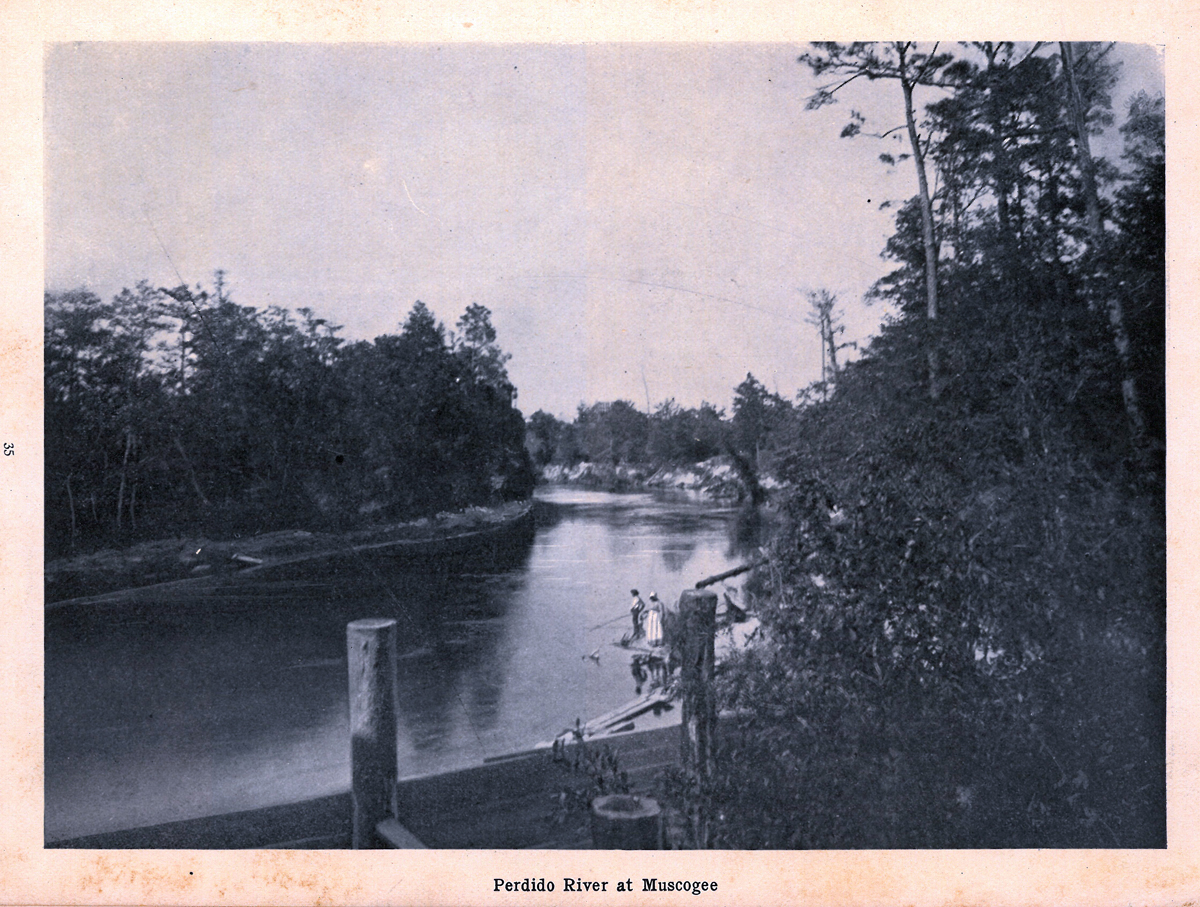

The Perdido River near Muscogee, Florida – photo from The Perdido Country, a promotional pamphlet issued by the Southern States Lumber Company (1903). A copy is available in the State Library’s Florida Collection.

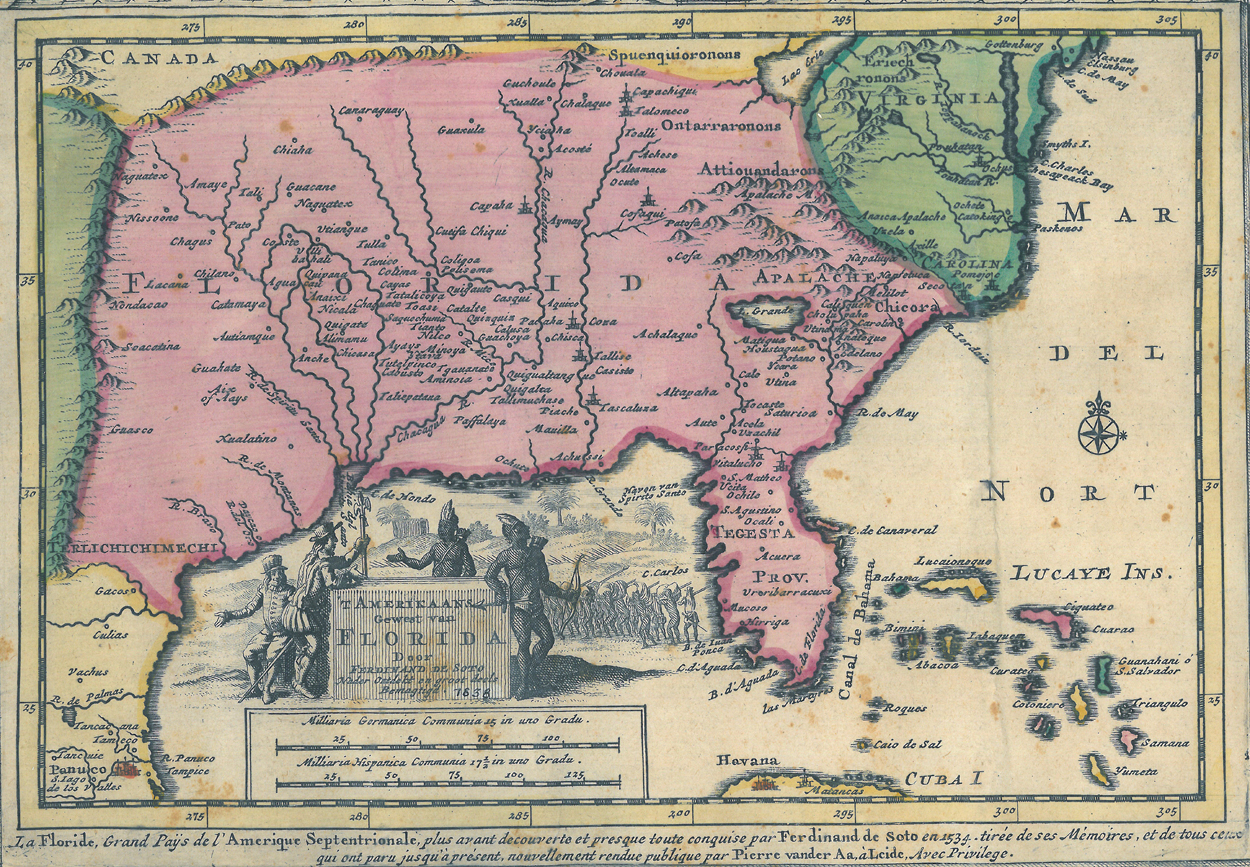

The frequent changes in Florida’s boundaries before 1821 were symptomatic of a broader competition between European empires (and later the United States) for territory on the North American continent. Spain, France, and Great Britain all established colonies that expanded, contracted, and shifted according to their respective fortunes and priorities. As a result, early maps of North America generally give a very vague sense of where Florida was supposed to be. After Juan Ponce de Leon claimed Florida for Spain in 1513, the Spanish continued exploring the present-day Southeastern U.S. and expanding their claims to the land. At various times maps show Spanish Florida reaching as far west as Texas and as far north as the Carolinas and the present-day Midwest!

An example of Florida’s once-enormous boundaries. Pictured here is “‘T Amerikaans gewest van Florida door Ferdinand de Soto,” a map prepared by Pieter van der Aa (circa 1710s). Click the map to enlarge it.

Florida’s western boundary came into slightly sharper focus once the French began establishing themselves in the Mississippi Valley in the 17th century. In 1682, explorers Robert de La Salle and Henri de Tonti followed the Mississippi River southward from present-day Illinois toward the Gulf of Mexico. They claimed the entire Mississippi Valley for France, naming it Louisiane in honor of King Louis XIV. This conflicted with Spain’s claims to the Gulf South region, and the Spanish began sending out missions to see what the French were up to. Finding that the French were indeed active in the area, Spanish authorities rushed to establish a presence at Pensacola Bay in 1698.

They did so just in time, as French explorer Pierre le Moyne d’Iberville arrived at the mouth of the bay in January 1699. The Spanish denied d’Iberville passage into the bay, and to their relief his ships eventually headed back west, the explorers satisfying themselves by founding Biloxi and Mobile. So long as the French held Louisiana, however, they never entirely forgot about Pensacola Bay. Indeed, they later invaded and occupied the settlement for a few years during the 18th century.

Evidence for a treaty establishing an exact boundary between Spanish and French possessions along the Gulf is sketchy, but some historians have claimed such an agreement was reached in 1702, with the Perdido River as the dividing line. Regardless of whether an actual treaty was signed, the Perdido River generally came to be accepted as the effective line of demarcation, since French influence had been checked by the presence of the Spanish at Pensacola.

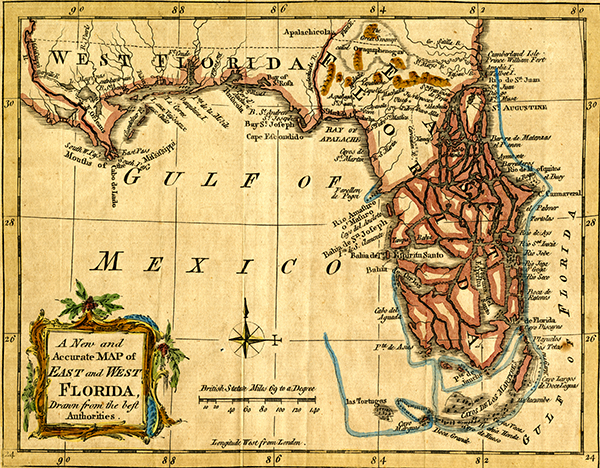

Fast forward to the 1760s. France and Spain were allied against Great Britain in the French & Indian War (or Seven Years’ War), and losing badly. At the treaty negotiations that followed the conflict, Spain gave up Florida to the British in exchange for Havana. The French also ceded the eastern half of Louisiana to Britain, effectively giving the British possession of all the territory from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River that they didn’t already have. The British decided to carve two “Floridas” out of the coastal region they had just acquired. East Florida would contain the Florida peninsula and the Panhandle west to the Apalachicola River. West Florida would contain everything from the Apalachicola River west to the Mississippi River, including the former Spanish settlement at Pensacola and the French outposts at Mobile and Biloxi.

This map shows the boundaries of the new provinces of East Florida and West Florida right after they were created following the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. The map is entitled “A New and Accurate Map of East and West Florida.” Florida Map Collection, State Library. Click the map to enlarge it.

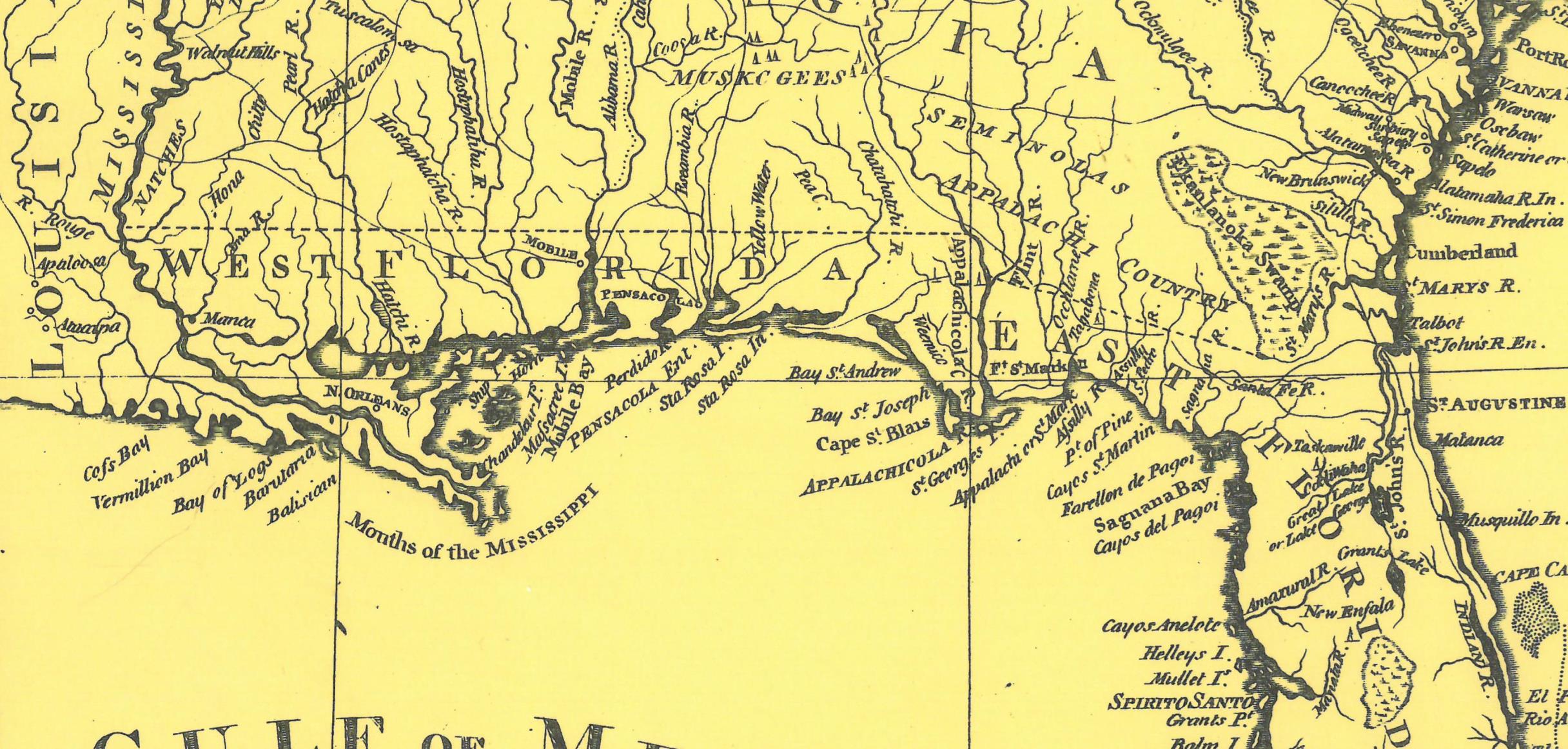

The British held onto the two Floridas until the treaty negotiations following the end of the American Revolution in 1783. The United States acquired the former British colonies as far south as Georgia, but Spain acquired East and West Florida in a separate agreement. The Spanish had already received what was left of French Louisiana by this time, which meant the Spanish once again had control of the entire northern rim of the Gulf of Mexico. Administratively, however, the Spanish kept “Florida” and “Louisiana” separate, as we see below.

Joseph Purcell’s map of the Southern States, plus East and West Florida (1792). Florida Map Collection, State Library. Click the map to enlarge it.

In 1800, Spain ceded Louisiana back to France under the Treaty of Ildefonso, but retained East and West Florida. Three years later, U.S. and French authorities negotiated the Louisiana Purchase, which transferred the over 800,000 square miles of French Louisiana territory to U.S. ownership.

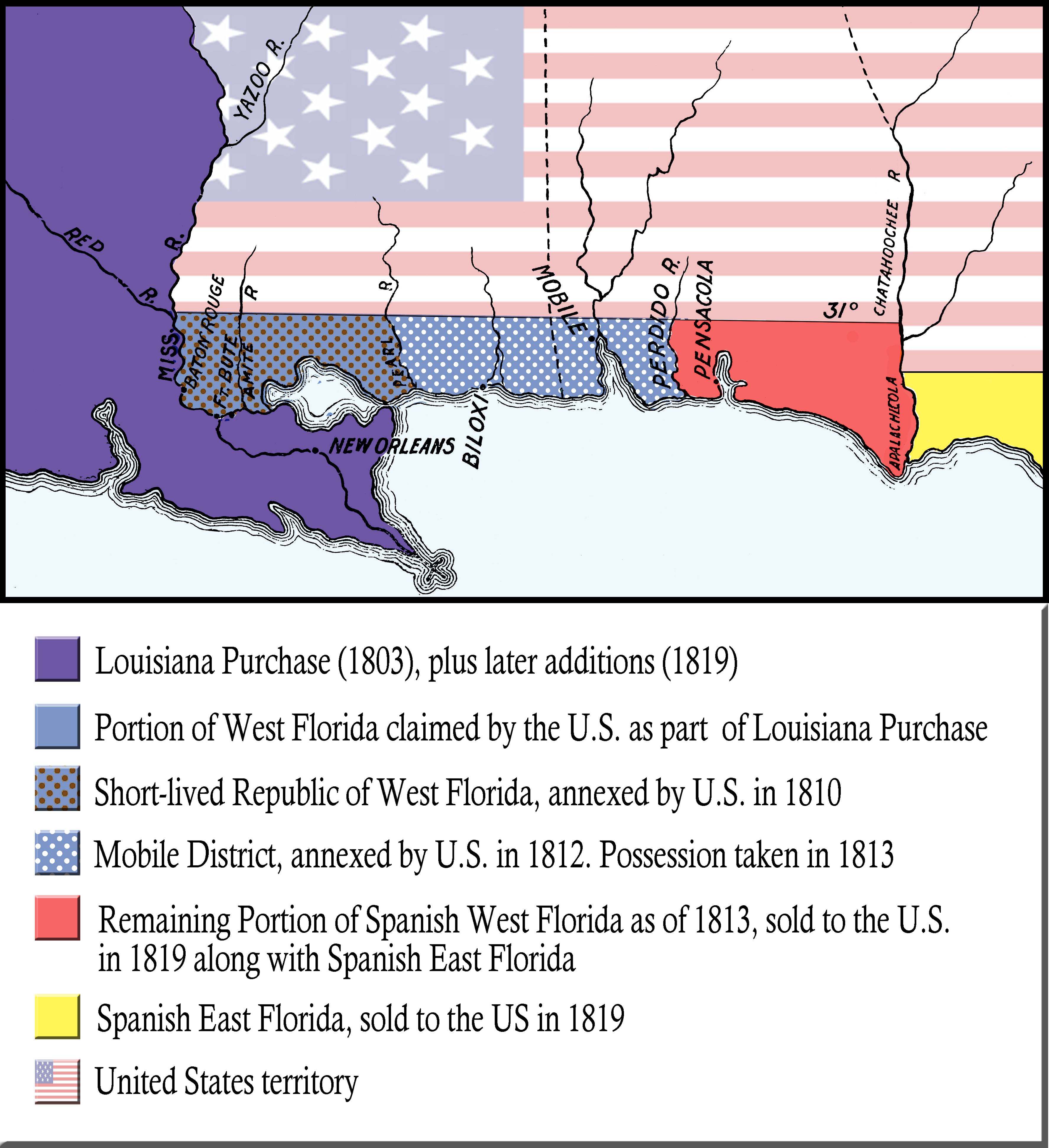

Here’s where things got a little tricky. The U.S. claimed that West Florida was part of the Louisiana Purchase, since West Florida up to the Perdido River had been part of Louisiana when the French first established the province in the 17th century. Spain, owner of East and West Florida since 1783, protested strongly, but it was facing bigger problems at the time and had little appetite for resistance. U.S. settlers began moving into West Florida, despite the fact that Spain was still claiming ownership up to the Mississippi River.

This state of affairs was bound to lead to trouble, and in 1810 it did. A group of English-speaking West Floridians rebelled against the local Spanish governor, overwhelmed the Spanish garrison at Baton Rouge, and declared the portion of West Florida between the Mississippi and Pearl rivers an independent republic. The West Floridians promptly reached out to U.S. authorities to negotiate for annexation or admission as a state. President James Madison declared, however, that West Florida was already U.S. property because of the Louisiana Purchase. In December 1810, the U.S. military governor of the neighboring Orleans territory, William C.C. Claiborne, took possession of the short-lived republic of West Florida. It was eventually incorporated into the state of Louisiana, although it is still known locally as the “Florida Parishes” region.

Map showing the transformation of West Florida (1803-1819). Based loosely on a map in Henry Edward Chambers’ “West Florida and Its Relation to the Historical Cartography of the United States,” Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science XVI, no. 5 (May 1898). Modified by the Florida Memory staff for clarity.

The rest of Spanish Florida wasn’t far behind in falling to United States control. In 1813, U.S. General James Wilkinson sailed from New Orleans to Mobile and demanded the surrender of the Spanish commander there. The official complied, giving the United States control of the so-called “Mobile District” between the Pearl and Perdido rivers. This land was annexed to the Mississippi Territory, which was later split into Mississippi and Alabama.

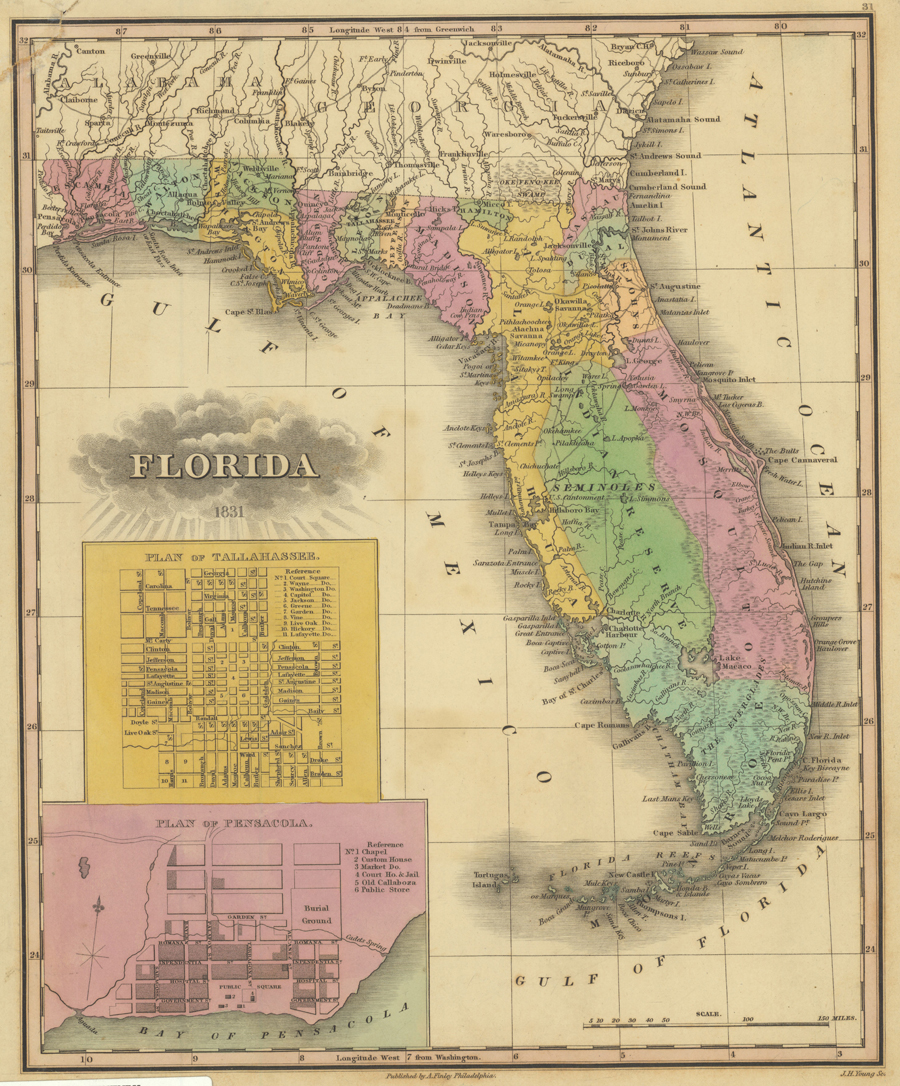

That left Spain holding only the piece of West Florida between the Perdido and Apalachicola rivers, plus all of East Florida. In 1819, Spanish authorities agreed to sell these Floridian possessions to the United States, whose leaders then combined the two Floridas into the unified Florida we know today. The Perdido River became the permanent western boundary, because by that time the parts of West Florida west of the Perdido were already incorporated into Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

A. Finley’s map of Florida (1831), showing Florida’s current boundaries, except for a small error near the St. Marys River. Florida Map Collection, State Library. Click the map to enlarge it.

The State Library’s Florida Map Collection contains over 2,000 historic maps and charts illustrating the geography of Florida, North America, and the Western Hemisphere. A selection of these maps are available for viewing on Florida Memory.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "When Florida Touched the Mississippi." Floridiana, 2015. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/297532.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "When Florida Touched the Mississippi." Floridiana, 2015, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/297532. Accessed February 13, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2015, September 9). When Florida Touched the Mississippi. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/297532

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program