Description of previous item

Description of next item

Here Today, Gone Tomorrow

Published March 3, 2016 by Florida Memory

Florida has long been a place where people come to make a fresh start. In some cases, eager newcomers have built entire communities from scratch, hoping either to strike it rich or to carve out a safe space to practice a particular way of life. Hall City, a planned community located near the southwest shore of Lake Okeechobee in what is now Glades County, was built with both objectives in mind. First advertised around 1910, it was designed to turn 30,000 acres of piney woods and Everglades muck into a thriving Christian agricultural and educational center.

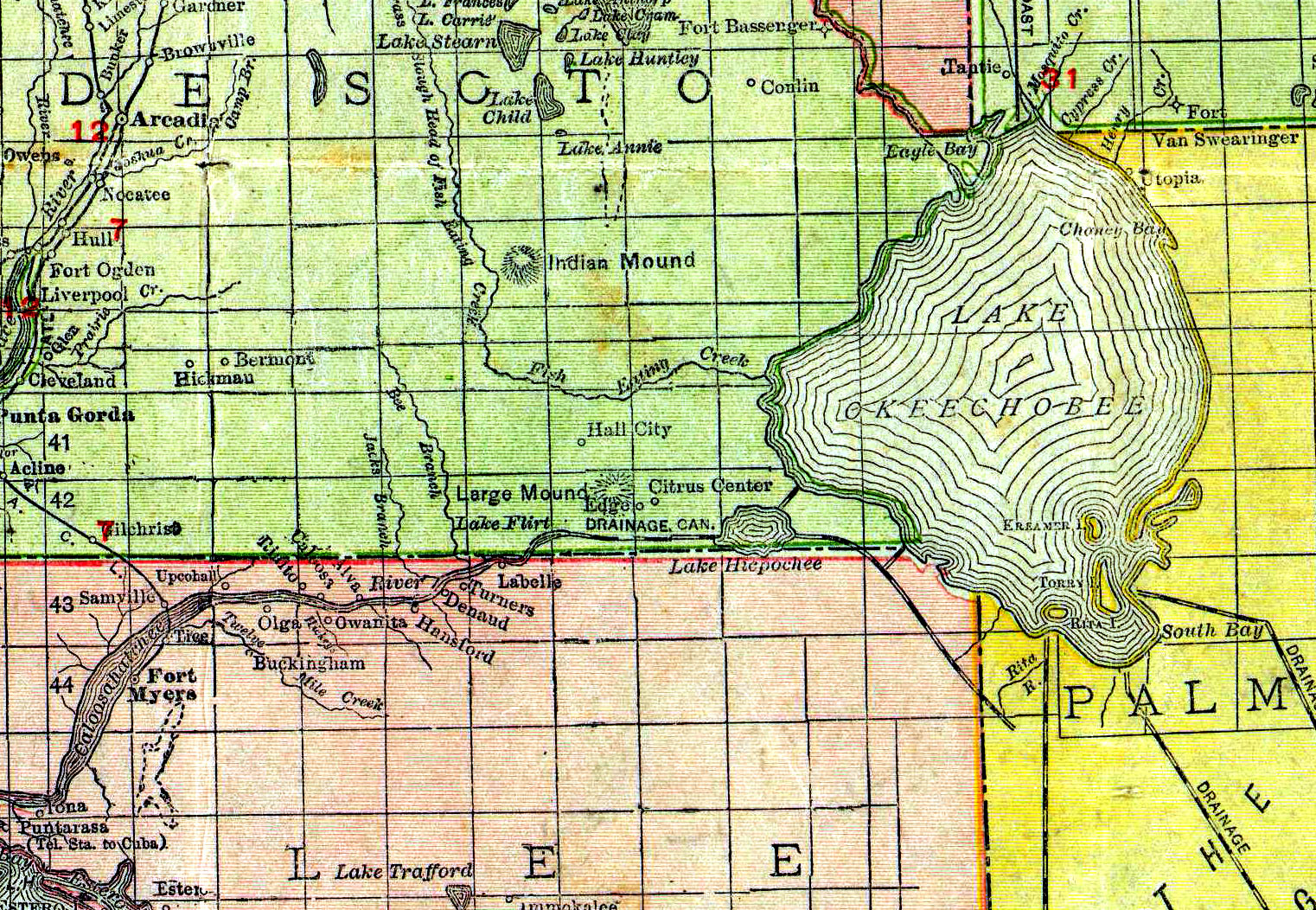

Excerpt of a 1912 Rand McNally map showing Hall City and the surrounding area. Notice that at this time Hall City was located in DeSoto County. In 1921, four additional counties were carved out of DeSoto, including Glades County, which now contains the Hall City site. Florida Map Collection, State Library of Florida. Click the map to enlarge it.

Hall City was the brainchild of Dr. George Franklin Hall, an Iowa native who established himself as a pastor and prolific writer in the Midwest in the late 19th century. He moved in 1900 to Chicago, where he pastored his church without salary while supporting his family on the proceeds of his writing and his investments. Around 1910, Hall began running newspaper ads for “La Belle Park,” a Christian colony in South Florida where temperance-minded families could build farms in a wholesome environment devoid of intoxicating drink. Hall was already busy breaking the land into 10-20 acre parcels, which he offered for sale at about $30 per acre. The settlement should not be confused with the nearby town of La Belle, which was settled decades before Hall came on the scene.

George Hall spared no effort to praise La Belle Park land as capable of growing everything from oranges to eggplants to strawberries to – as he put it – “everything else that tastes good and commands a high price in the Northern markets in January, February, and March.” The pastor-promoter promised easy terms for land, and offered to reward cash buyers with free town lots in Hall City, the planned capital of this new Christian utopia. Hall envisioned a bright future for his namesake town, including service from three railroads, escalating land values, and even a Christian college to be called Hall University. Hall set aside 160 acres for this institution adjoining the Hall City town site. He planned to plant 120 acres of the tract in citrus trees, which the students would manage themselves in order to offset the cost of tuition. By a combination of Christian teaching and purposeful labor, Hall intended for his university to become “a real developer of mind, muscle, and morals.”

The pastor’s enthusiasm for attracting new residents had a few limits. In newspaper advertisements, Dr. Hall stated that he would sell no land to African-Americans or “recently imported foreigners from the south of Europe.” Also, the town’s temperance theme was more than just a suggestion – it was legally woven into the residents’ land titles. Hall required all purchasers to sign deeds containing a “perpetual prohibition clause” forswearing the consumption of alcohol on the premises.

Despite these restrictions, settlers began purchasing the land and Hall City began to take shape over the next year. Hall sent his son George Barton Hall to run the operation, and soon the fledgling town had a general store, a hotel, several homes, and a post office. Curbs and sidewalks went in, and the Atlantic Coast Line established a depot for Hall City on its spur line headed south to Everglades City.

Even with these early signs of success, however, Hall City was in for a rough ride. It turned out that the swamp and piney woods surrounding the town were not as fertile as Dr. Hall had led the settlers to believe. Also, the Atlantic Coast Line spur was the only railroad that ever entered the town, which left residents without convenient connections to either coast. There was no major highway nearby; in fact the only Hall City automobile ever registered with the state was the one pictured above belonging to George Barton Hall. The biggest blow was the entry of the United States into World War I, which drew many of Hall City’s residents into the military or war-related industries elsewhere.

George Barton Hall, Jr., the first child born in Hall City. The building across the street was the office of his father George Barton Hall, Sr., general manager of the planned community (photo 1915).

By 1918, the only business left operating in town was the Hall City Mercantile Company store, and it was living on borrowed time. The post office had already closed; mail service was routed through nearby La Belle or Palmdale. The Atlantic Coast Line eventually abandoned the spur passing near Hall City and took up the tracks. Most of the land was forfeited for taxes and bought up by large corporations, although Glades County officials have received inquiries from heirs of the original owners as recently as the 2000s. The Hall City town site is inaccessible to the public, as it is surrounded by privately owned land with no public roadways running through it.

Little evidence of the town remains aside from a few sandy roadbeds and fragments of sidewalk here and there. According to Glades County old-timers, most everything of value was removed from Hall City for use elsewhere once it was clear the settlement had failed.

Hall City’s story is remarkable, but not unusual. Hundreds of similar ghost towns and “map dots” are located throughout the state, each with its own story of rise and decline. What ghost towns or “map dots” exist in your Florida county? What has been done to preserve their stories? Get the conversation started by sharing this post on social media, or leave us a comment below.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Here Today, Gone Tomorrow." Floridiana, 2016. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321974.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Here Today, Gone Tomorrow." Floridiana, 2016, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321974. Accessed February 13, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2016, March 3). Here Today, Gone Tomorrow. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321974

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program