Description of previous item

Description of next item

St. Vincent Island

Published April 4, 2016 by Florida Memory

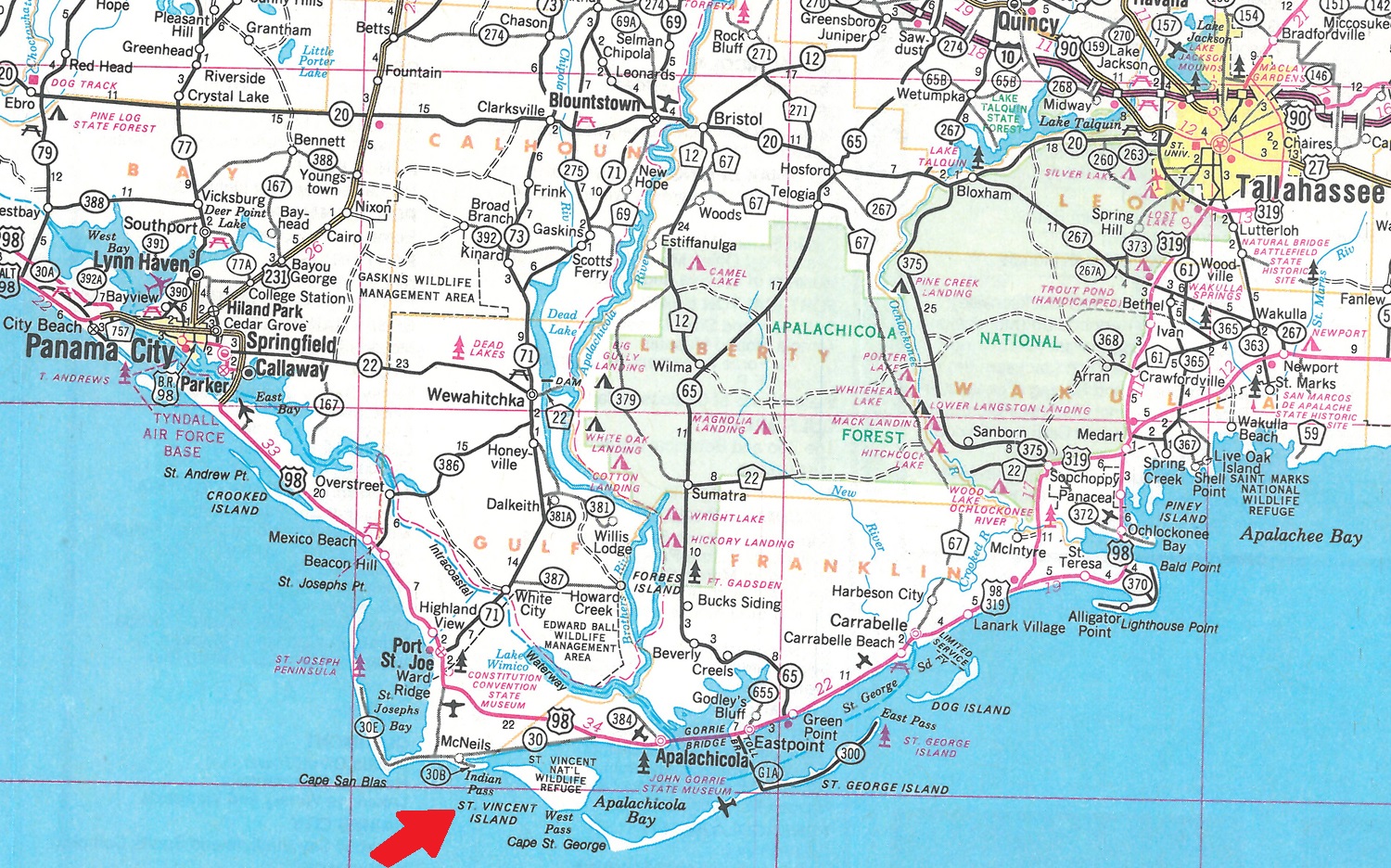

How much history can one island hold? If you’re looking at the barrier islands and keys off the coast of Florida, the answer is quite a lot. Take St. Vincent Island, for example. It’s a barrier island guarding the western entrance to Apalachicola Bay in the Florida Panhandle. Geologists estimate the island to be a mere 4,400 years old, but in that time it has been an outpost for Confederate soldiers, a cattle ranch, a resort and hunting preserve for rich tourists, a Spanish military camp, and a home for Native Americans.

Excerpt of a 1992 Florida Department of Transportation map showing St. Vincent Island and the surrounding area. Click the map to enlarge it.

St. Vincent Island is about 12,300 acres in size, with fourteen miles of beaches on the eastern and southern shores. It is sandwiched between St. George Island on the east and a small spit of land jutting out from Cape San Blas on the west. Indian Pass, which separates the island from the mainland, has historically been too shallow for major ship traffic, but the gap between St. Vincent and St. George islands (known as West Pass) was once a critical commercial entrance to Apalachicola Bay. The terrain is a microcosm of Florida itself, featuring small freshwater lakes, hills, forests of virgin pine growth, and swamps. Its first human residents were Native Americans who lived about 2,000 years ago. Archaeologists have located pottery shards and shell middens testifying to their stay.

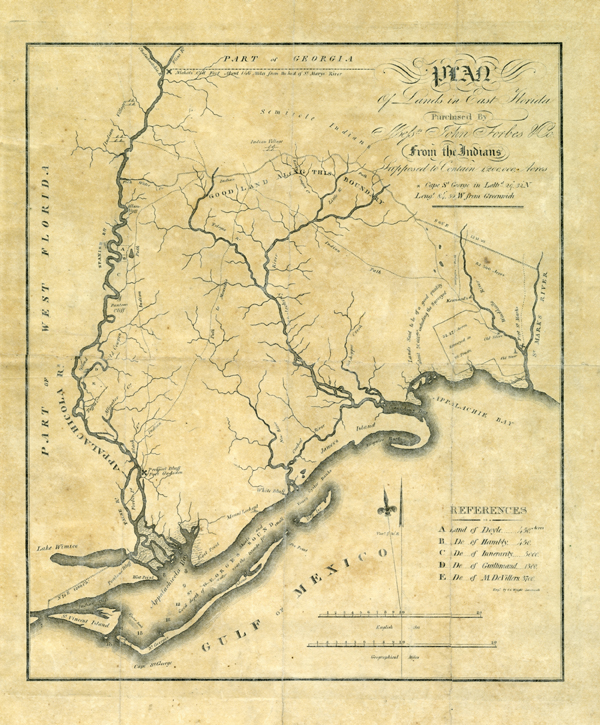

Documentation of the island’s naming is scant, but the reigning theory is that Franciscan friars working with the Apalachee tribes during the first Spanish colonial period named the island after St. Vincent, a martyr of the fourth century. Creek and Seminole Indians eventually made it to St. Vincent Island, replacing the earlier native tribes whose numbers dwindled from disease and battle following the arrival of the Europeans. Spanish forces also used the island in 1815 as a temporary refuge while operating in the Apalachicola River valley.

In 1811, Creek and Seminole leaders added St. Vincent Island to a large land grant designed to settle their debts to John Forbes and Company, a British trading firm. This land grant was known as the Forbes Purchase, and ultimately consisted of about 1.5 million acres of territory between the Apalachicola and Wakulla rivers.

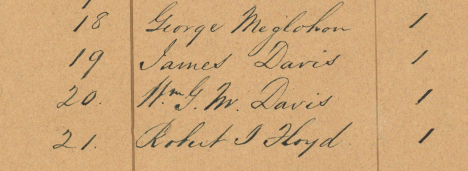

The validity of the Forbes Purchase was challenged once Florida became a U.S. possession in 1821, but the successors of the Forbes firm held title to St. Vincent Island until 1858, when they sold the land to Robert Floyd, a lawyer in nearby Apalachicola. Floyd and his young son Gabriel lived on the island, most likely at a point overlooking West Pass. The elder Floyd was serving as a collector of customs for the United States government as of 1860.

Excerpt on an 1845 election return from Franklin County showing Robert J. Floyd as a voter. Click on the image to view the entire return, part of the 1845 Election Returns collection on Florida Memory.

Despite its strategic view over the western route into Apalachicola Bay, St. Vincent Island played a relatively limited role in the Civil War. Several companies of the Fourth Florida Infantry commanded by Colonel Edward Hopkins occupied the island during the summer of 1861, but Governor John Milton ordered the island and all supplies and equipment removed later that year. The Confederates did build a small fort on the island, which they called Fort Mallory in honor of Stephen Mallory, Confederate Secretary of the Navy. It was short-lived, however. When Union naval personnel from the East Gulf Blockade Squadron landed on St. Vincent in December 1861, they reported that the fort had been dismantled and deserted.

Letter appointing Dr. C.C. Burke as Surgeon for Confederate troops on St. Vincent Island (1861). Click the image to enlarge it.

By the time the war had ended and things were getting back to normal, Gabriel Floyd had died, leaving the ownership of St. Vincent Island in turmoil yet again. George Hatch, a banker and former mayor of Cincinnati, purchased the island for $3,000 at public auction and lived there for a time. He died in 1875 and was buried on the island, making his the only marked grave on St. Vincent.

Grave of George Hatch, owner of St. Vincent Island from 1868 to his death in 1875. This is the only marked grave on the island (photo 1970).

Hatch’s family remained on St. Vincent Island for a number of years before selling it in 1890. Ownership passed in 1907 to Dr. Raymond Vaughn Pierce, a physician from Buffalo, New York. Pierce had made a fortune manufacturing patent medicines with names like “Dr. Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery” and “Dr. Pierce’s Pellets.” He also published a book entitled The People’s Common Sense Medical Advisor in Plain English.

Pierce decided to transform the island into a resort and hunting preserve. He constructed a number of cottages and buildings for his family and guests, and imported a variety of exotic wildlife, including the Sambur or India deer, Japanese deer, and Chinese antelope. He also maintained a number of food crops and a herd of cattle to supply his table. A thousand wild hogs and three to four hundred head of cattle were estimated to roam the island during the 1920s.

Dr. Pierce died on St. Vincent Island in 1914, but his descendants continued to run the island for a number of years. During World War II, large portions of the island’s virgin yellow pine timber were cut and transported over a makeshift bridge to the mainland. The Pierce family also began leasing oystering rights to outside parties in order to make money. The family sold St. Vincent Island in 1948 to brothers Henry and Alfred Loomis, who sold it in 1968 to the Nature Conservancy. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service promptly designated St. Vincent Island as a National Wildlife Refuge, which it remains today.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "St. Vincent Island." Floridiana, 2016. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321976.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "St. Vincent Island." Floridiana, 2016, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321976. Accessed February 13, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2016, April 4). St. Vincent Island. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321976

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program