Description of previous item

Description of next item

Step Aboard for the Gospel of Good Health!

Published July 7, 2017 by Florida Memory

From livestock and citrus to passengers and freight, Florida’s intricate railroad network has served the commercial interests of the state since the mid-19th century.

But, between 1915 and 1917 the railroads also helped meet the public health needs of the state.

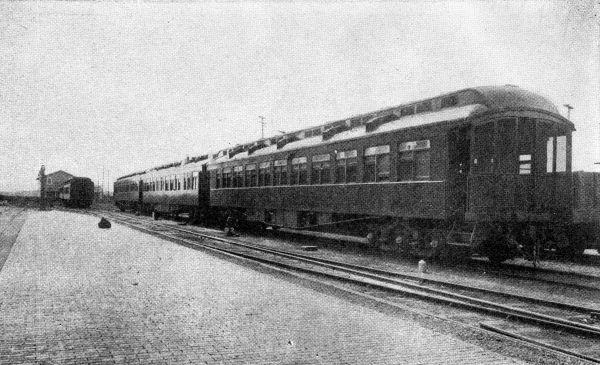

In those years, Florida State Board of Health officials kept the rail lines hot as they traveled aboard Florida’s Educational Health Exhibit Train, or exhibit cars equipped with the latest techniques for preventing disease and preserving good health. The health train stopped at nearly every juncture in the state, ready to share the “gospel of good health” with any Floridian who would listen.

The abbreviated history of the Florida health train illuminates how the private-public partnership between southern rail lines and the state health board worked to educate people on how to maintain good health.

View of Florida’s health exhibit train, 1916. Florida Health Notes, January 1916, page 416, State Library of Florida.

Florida’s Expanding Railroads

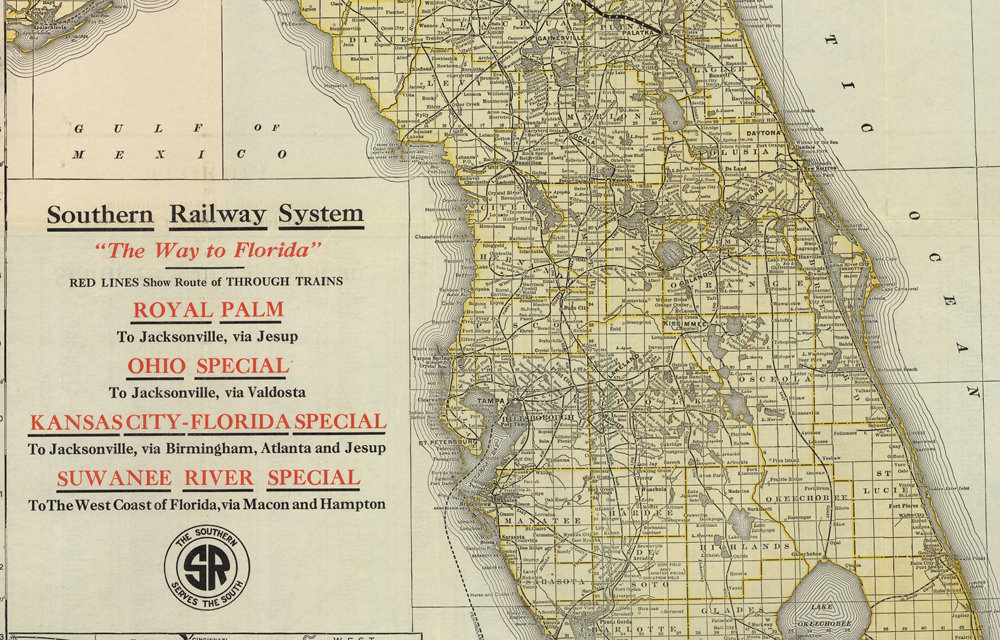

Map of Florida’s railroads, 1915. Florida Map Collection, State Library of Florida. (Click to enlarge and view full record.)

Beginning in the 1880s, Florida’s railroad infrastructure underwent rapid expansion. Powerful railroad investors like Henry Flagler, Sir Edward James Reed and Henry Plant oversaw the creation of expansive statewide rail systems with the hopes of attracting more tourists, permanent residents and industry to Florida. By 1900, over 3,000 miles of track weaved through the Sunshine State, and by 1912 Henry Flagler’s Florida East Coast Railway stretched from Jacksonville to Key West. The spread of the rails succeeded in bringing more people to the once sparsely populated state, expanding Florida’s population from 269,000 people in 1880 to 752,000 in 1910.

Disease by Rail

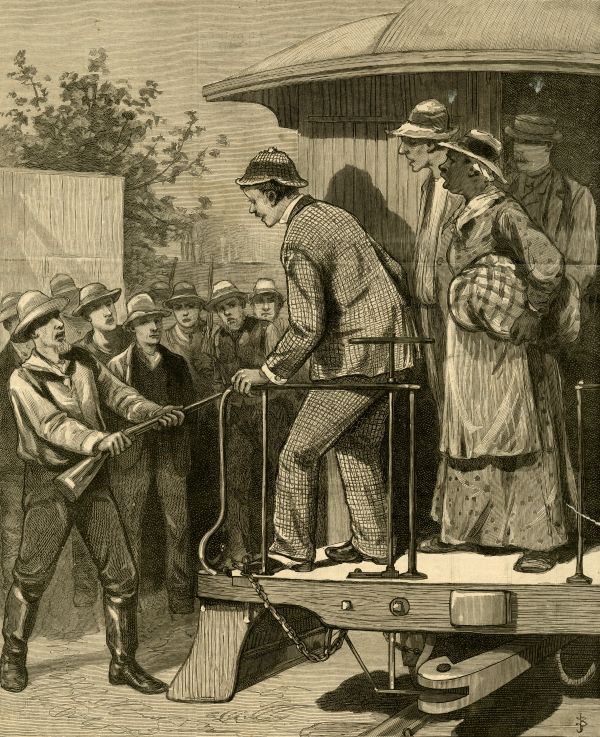

However, the spread of infectious disease began to emerge as an unintended, and deadly, consequence of the increased human interaction brought on by the the expansion of Florida’s mighty railroad empires. Mobs of southerners affected by Florida’s deadly yellow fever outbreaks of the 1870s, 80s and 90s frequently directed their anger and sense of helplessness toward the railroad companies, who, they believed were responsible for the spread of the disease.

Illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, depicting how during the yellow fever epidemic in Florida, “refugees were not allowed to leave the trains for fear of spreading the disease,” 1888.

For instance, in the summer of 1888, armed residents living in the tiny, but critical railroad junction of Callahan, Florida, threatened to destroy the local tracks if the Savannah, Florida and Western Railroad Company did not cease operations. But, the company refused to halt travel through the afflicted town and the disease spread. Thousands continued to perish of yellow fever until 1900, when scientists recognized it as a mosquito borne illness.

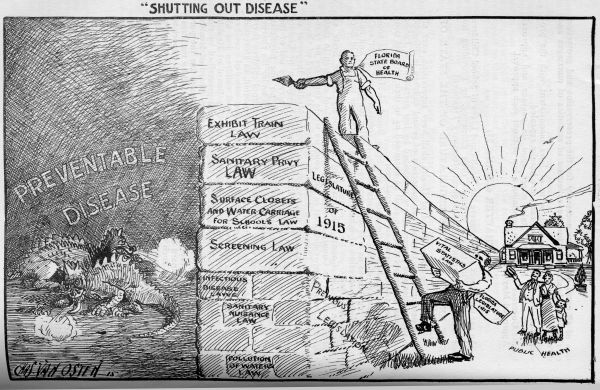

In the next few decades, the state reacted by passing several pieces of legislation aimed at mitigating future public health crises. Mandatory screens on windows, improved sewage infrastructure and potable water requirements were among the solutions. However, healthcare professionals warned that without proper education on these new techniques, lasting public health improvements would not occur. Indeed, smallpox, typhoid fever, malaria, hookworm and bad hygiene practices continued to claim countless lives well into the 1900s.

Flier for the anti-mosquito conference in Daytona, 1910. Florida’s incessant mosquito problem was proven as the cause of many diseases and health concerns. Prior to the health trains, state health officials traveled the state lecturing on mosquito-borne illness prevention techniques. Florida Bureau of Health Printed Matter (.S 908), Box 1, Folder 7, State Archives of Florida.

Even though state health officials had a new understanding of how these deadly diseases spread by the early 20th century, a lack of access to education on proper health habits, especially in Florida’s many rural communities, stalled public health progress.

Florida’s Educational Health Exhibit Train

Determined to educate all Floridians on how to stay healthy, State Health Office Joseph Y. Porter first created a large traveling exhibit intended for display in hotels, conference centers and other public spaces. Though the program was well-received, there were so many panels and displays that it proved too difficult to transport it throughout Florida as originally intended.

Florida’s health exhibit on display in an auditorium, January 1915. Florida Health Notes, January 1915, page 4, State Library of Florida.

Porter thought about how he could condense his message and reach more people. The health director looked to the innovative health train programs already chugging through Louisiana, North Dakota and Michigan for his answer. Doctors, nurses and attendants staffed these health trains and disseminated important health information to the public in a variety of formats.

Porter and his team sought to bring the traveling health exhibits to Florida. They were met with full support from the Railroad Commission, but the program required legislative consent.

Cartoon depicting the Florida State Board of Health “shutting out disease,” 1915. Note the allegorical brick with the label ‘exhibit train law’ on the top of the wall. Florida Health Notes, June 1915, page 204, State Library of Florida.

In 1915, the legislature approved the operation of the Educational Health Exhibit Train (Chapter 6894, Laws of Florida, 1915) among several other public health measures. The law “authoriz[ed] the purchase of cars for [use in the exhibits], and [permitted] the free transportation of them by any railroad compan[y].” The Pullman Company sold the board three wooden cars, equipped for exhibit features, for the reduced price of $500.00 each. The cars typically sold for no less than $15,000 apiece.

When the health train first pulled away from a Jacksonville depot in late 1915, officials expressed high hopes for its impact on public health:

“The entire state will be covered, stops being made at practically every railroad station thus bringing to every section of Florida, no matter how remote, the gospel of good health and disease prevention,” suggested a report published in the January 1916 volume of Florida Health Notes, the official bulletin of the State Board of Health.

The Exhibits

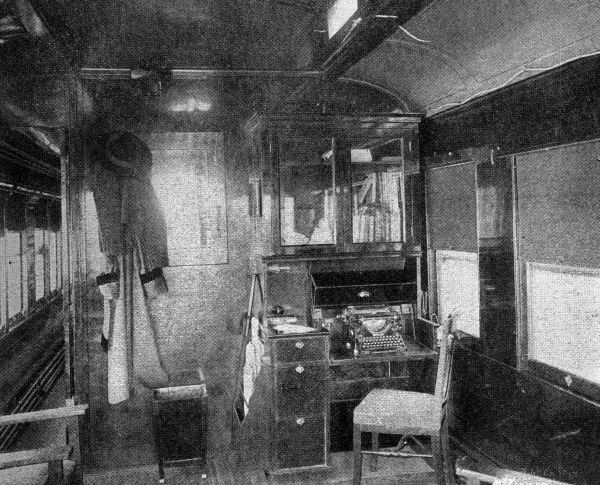

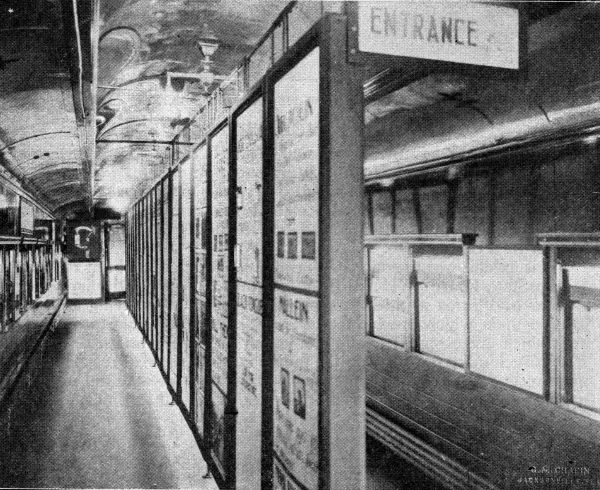

The traveling educational health exhibit consisted of three Pullman cars used to promote new sanitary living conditions and preventative health measures. One car was used exclusively for staff living quarters, while the other two housed educational film presentations, slideshows, public health demonstrations, models, electric devices, panel texts and numerous other instructional devices.

Interior view of car number one, which served as living quarters for Florida health train staff, 1916. Florida Health Notes, January 1916, page 415, State Library of Florida.

Interior view of the first exhibit car of the Florida health train, 1916. Florida Health Notes, January 1916, page 416, State Library of Florida.

The March 1916 volume of Florida Health Notes described the two exhibit cars in further detail:

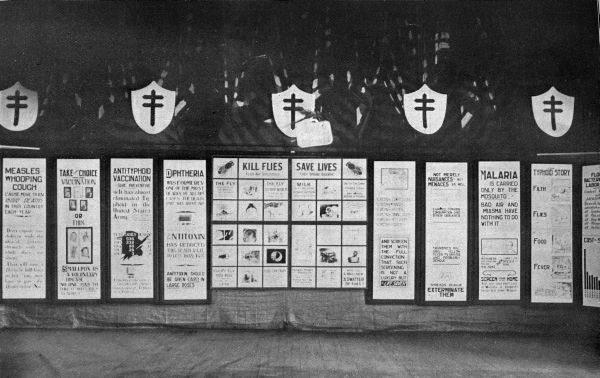

The larger part of the car is devoted to the installation of various models, as that illustrating the Imhoff sewage disposal system, another showing how water in driven or open wells is contaminated by drainage from stable, outhouse and polluted surface water. A miniature model shows a dipping vat for ridding cattle of the ticks, A model dairy is illustrated in the same manner; the proper feeding and clothing of babies and the open-air treatment of tuberculosis and many other practical questions of sanitation and disease prevention are similarly illustrated. … Car number three is divided through most of its length by a partition on which are displayed 36 panels. They carry… warnings and advice on sanitary subjects and disease prevention. Numerous electrically operated models and a large steremotograph (automated slide machine)… are also arranged[.]

State public health officials, including doctors and nurses, kept a tight schedule as they traveled all over Florida spreading the word about public health advancements. The program made regular stops in towns and cities along existing railroad routes, pulling in for a day or two at each location.

When the health train rolled into town, it typically attracted hundreds of visitors. School officials often planned a field trip around the train’s visit, sending their students to soak up the valuable hygiene lessons. Some teachers even awarded prizes to the student with the best essay describing what they had learned.

Interior view of the first exhibit car on the health train, 1916. Florida Health Notes, January 1916, page 147, State Library of Florida.

Gladys Brown, a seventh grade student from Green Cove Springs, a community near Jacksonville, published her observations in the April 1916 volume of Florida Health Notes.

Brown wrote about how when she first walked into the exhibit there was a model of an unsanitary kitchen. In it there were no screens and food had been left out on the dinner table, leaving it open to flies and possible contamination.

On the opposite side from this was shown a house… barn and other out houses. There was a large pile of fertilizer near by and the flies flew from this into the home, where of course, they [sit] on food, etc. There were chickens in the barnyard. One was dead, maybe of cholera. … Through the kitchen window I saw a kettle streaming on the stove. There were no screens to this window either–everything open to flies.

As Brown moved through the health train, she described informational panels about proper dental hygiene and slides with instructions on how to care for snake bites, dizziness and broken bones. Another display emphasized infant mortality, highlighting insufficient prenatal care, tuberculosis, diphtheria, whooping cough and scarlet fever as causes of death.

Brown documented that the exhibit concluded with a model of a sanitary home, replete with screened-in windows to keep flies and other bugs out and proper sewage.

“The last was a little bell which I had been hearing ring. It tapped every minute to remind you that someone died from a preventable disease.”

Closeup view of one the health education displays likely seen by patrons of the health train, 1915. Florida Health Notes, January 1915, page 5, State Library of Florida.

Although the trains ceased operation during the stifling summer months, the traveling health exhibit reached about 25 to 30 locations per month. Some of the stops included Cocoanut Grove, West Palm Beach, Titusville, New Smyrna, Walton, Maytown, Daytona, Palatka, Lake City and Jacksonville.

No community was too big or too small to receive the so-called gospel of good health, and by the close of 1916 the health train had visited a total of 126 towns in Florida.

Dr. Porter took great pride in the innovation, writing in his 1916 Annual Report to the State Board of Health:

It can be said without any undue boast or immoderate brag, that the Educational Health Exhibit Train has been the crowning feature of the health administration of the past four years…The Train affords the means of bringing the subjects which the State Board of Health believes to be of prime importance to the welfare of the people in Florida in their health and happiness…along the lines of rail communication. (This) moving school of instruction… represents a striking effort toward the sole object of improving the human health…and the State…hopes through this means to impress the people…with useful lessons of not only how to live healthily and therefore happily, but also how to live long and monetarily profitably. The…fruitful benefit resulting from the visit of these cars equipped with an exhibit is purely educational in character of a sanitary and hygienic nature…is clearly shown by request from the people…for literature giving additional information on disease prevention and improved manner of keeping in the health.

In 1917, the program reached another 78 towns, but the successes of the Educational Health Exhibit Train were short-lived. When Dr. Porter resigned later that year, interest in the program faded. With that, the state sold the exhibit to a carnival and the health trains became history.

Selected Sources:

Huffard, Scott R., Jr. “Infected Rails: Yellow Fever and Southern Railroads.” Journal of Southern History. 79.1 (Feb. 2013): p. 80.

Turner, Gregg M. A Journey into Florida’s Railroad History. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008.

Florida Health Notes, 1915-1917. State Library of Florida.

Annual Report of the Florida State Board of Health, 1916. State Library of Florida.

(.S 900) Florida State Board of Health Subject Files. State Archives of Florida.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Step Aboard for the Gospel of Good Health!." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332809.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Step Aboard for the Gospel of Good Health!." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332809. Accessed February 13, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, July 7). Step Aboard for the Gospel of Good Health!. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332809

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program