Description of previous item

Description of next item

The Mariel Boatlift of 1980

Published October 10, 2017 by Florida Memory

Between April and October of 1980, approximately 125,000 Cubans seeking refuge from Fidel Castro’s regime packed into a total of 1,700 boats in Mariel Harbor, Cuba, and journeyed to southern Florida. Twenty-five thousand more Haitians escaping the dictatorship of Jean-Claude Duvalier also arrived during this period. The mass exodus opened a new chapter in America’s long immigration history and permanently altered Florida’s cultural identity.

As the Mariel Boatlift got underway, the media converged on the south Florida points of entry, eager to record history in the making; local Key West photographer Dale McDonald was among them and later donated his images of the boatlift to the State Archives of Florida. McDonald’s photographs illustrate how the Mariel Boatlift unfolded on Florida’s southern shores.

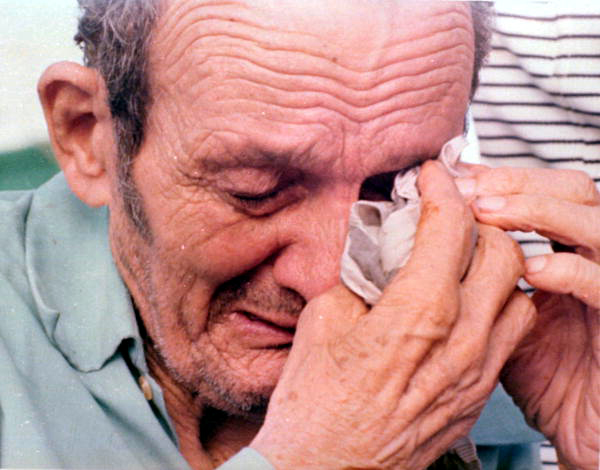

Cuban refugee breaks down after arriving in Key West during the Mariel Boatlift. Photograph by Dale McDonald, 1980.

Cuba, Florida and Cold War Immigration Policies

Though the sudden influx of Cubans definitively reshaped Florida’s demographic makeup, the exodus of 1980 was preceded by 20 years of steady Cuban immigration to Miami. In 1959, Fidel Castro had led the Cuban Revolution, overthrowing the American-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista and installing a new communist government.

Castro restricted American influence on the island and by the early 1960s had seized American-owned property in Cuba. Two incidents in the early 1960s, the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis, further strained tensions between the two nations. Many Cubans, especially the well-heeled and those with ties to Batista, feared they would be targeted by Castro. Thousands fled to the United States. In light of this Cold War reality, President John F. Kennedy approved the Cuban Refugee Assistance Program (CRA) in 1961 to provide health, employment and educational services to Cuban refugees. The Florida Department of Public Welfare oversaw the program until 1974.

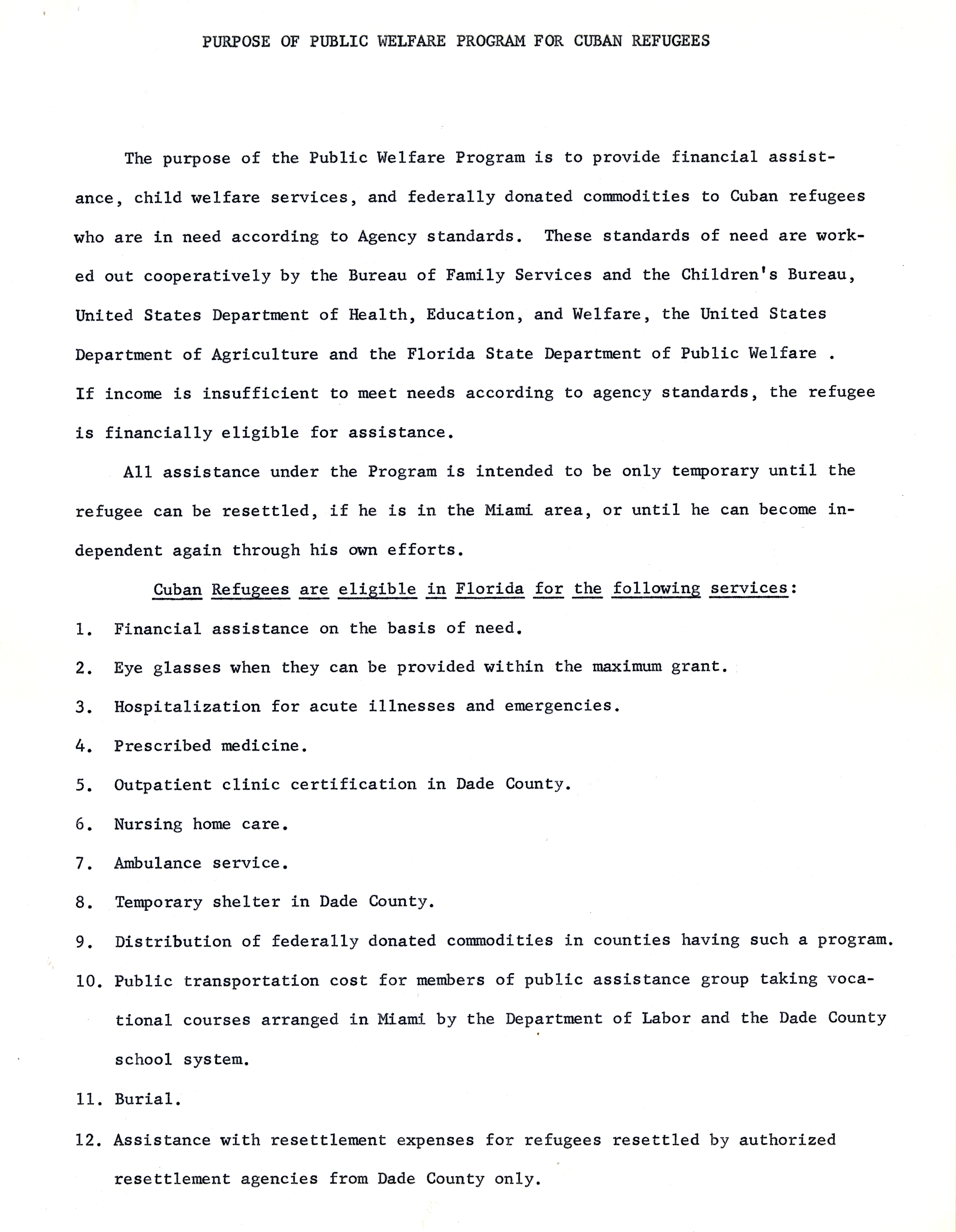

This document was intended for distribution to Cuban refugees to help them understand the assistance available through the CRA, 1963. Click to enlarge and view full record. Click here to view additional resources on the Cuban experience in Florida.

By the late 1970s, over 700,000 refugees had fled Cuba for the United States. Considered political asylum seekers, the majority settled in Dade County, where a distinct Cuban-American enclave emerged in Miami. In 1978, tensions between the United States and Cuba thawed and a series of conferences, known as Dialogos (dialogues), took place between Cuban officials and prominent members of the exile community. The Dialogos resulted in the creation of a travel policy that allowed approximately 100,000 exiles living in the United States to visit Cuba. The relaxation of Cuban-U.S. relations in the late 1970s inadvertently increased pleas from Cubans wishing to leave the island

The 1980 Cuban Exodus

In March 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed the 1980 Refugee Act which established standardized guidelines for refugee resettlement in the United States. Though the law capped the number of refugees permitted to enter the country through 1982 to 50,000, it did grant the president authority to increase the refugee limit for “humanitarian purposes.” Political unrest brewing in Cuba would soon test that caveat.

In early April 1980, a group of 10,000 Cubans, frustrated with the depressed economic climate of the communist regime, stormed the Peruvian Embassy in Havana and demanded political asylum.

Days later, on April 20, President Castro responded to the outbreak of social dissent. He announced that all Cubans wanting to leave the island could do so, as long as they left from Mariel Harbor, a port 25 miles west of the capital of Havana, and had someone waiting to retrieve them.

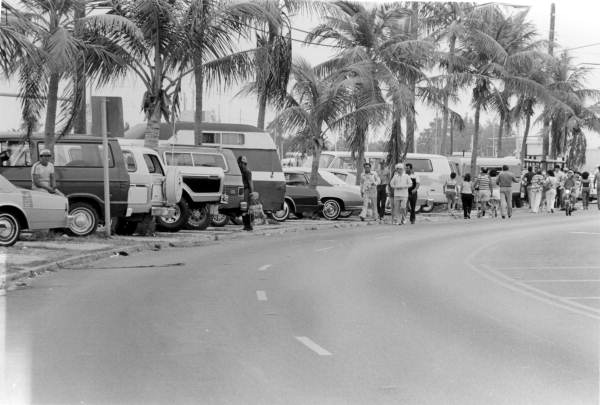

Parked cars line N. Roosevelt Street in Key West as hundreds of Cuban exiles walk to nearby Garrison Bight Marina with the intention of retrieving family members in Mariel, Cuba. Photograph by Dale McDonald, 1980.

Boats sit docked at the Garrison Bight Marina before embarking on the 125-mile journey from Key West to Mariel, Cuba. Some private boat owners took financial advantage of the Cuban exile community’s desperation to meet their relatives at Mariel, selling rides for upwards of $10,000 and charters for not much less. Photograph by Dale McDonald, 1980.

Within hours of Castro’s decree, the freedom flotilla began. Cuban exiles living in south Florida began making arrangements, such as buying or chartering boats from local private owners, to pick up relatives still living on the island. On April 21, the first boat from Mariel docked in Key West with 48 Marielitos, as this wave of Cuban refugees became known.

By April 25, a reported 300 boats were waiting in Mariel Harbor. While some refugees boarded boats supplied by family members, Cuban officials packed thousands more into old fishing vessels.

The shrimp boat “El Dorado” arrives in Key West packed with Cuban refugees from Mariel. Overcrowded boats were at risk of capsizing and a total of 27 refugees died en route to Florida during the Mariel Boatlift. Photograph by Dale McDonald, 1980.

Haitian “Boat People”

At the same time that the Marielitos began arriving in Florida en masse, thousands of Haitian “boat people” did, too. Beginning in the late 1950s, soon after the totalitarian Duvalier regime took hold, Haiti’s exiled politically-connected and middle-class professionals first began immigrating to south Florida, often by way of airplane. Then, in the 1970s, Haiti’s rural and urban poor also started fleeing the country for Florida via boat, for which they became known as Haitian “boat people.” By 1979, an estimated 10,000-23,000 Haitians resided in south Florida. When Castro announced the opening of the port at Mariel the next year, droves of Haitians would take the opportunity to join the Cuban exodus and immigrate to the United States.

Florida and the Mariel Boatlift

Already mired in foreign policy controversy with the ongoing Iranian Hostage Crisis, President Carter waited three weeks before authorizing the direct involvement of federal government officials to help with the intake of Marielitos.

Private vessels “Foxy Lady” and “Matilde” filled with Cuban refugees from Mariel docked at Pier “B” in Key West. After disembarking, passengers walked from the pier to the makeshift immigration processing center at the Key West Latin Chamber of Commerce. Photograph by Dale McDonald, 1980.

Thus, during the first month of the Cuban exodus, as the federal government weighed the risks of federal involvement in the Cold War controversies surrounding the boatlift, much of the responsibility associated with the unexpected processing, relocating and absorption of Marielitos became the primary charge of Florida’s state and local officials, the extant Cuban-American community and volunteers.

Ports in Key West, Opa-Locka and Miami opened makeshift immigration processing centers to accommodate the flood of Marielitos. As the southernmost point in Florida and shortest distance from Mariel, the small island town of Key West was especially overwhelmed by the wave of nearly 3,000 immigrants that arrived within the first 20 days of the exodus.

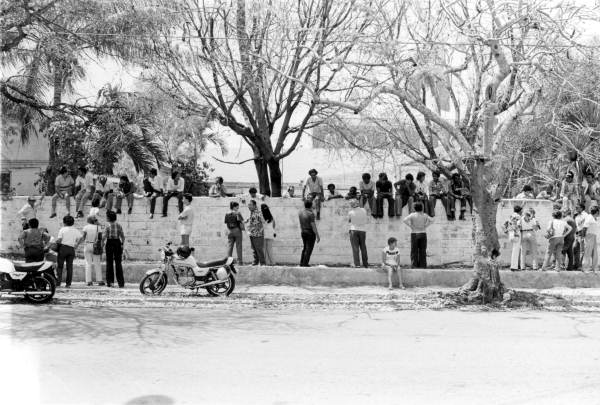

Family and friends of Cuban refugees arriving from Mariel wait outside of the Key West Latin Chamber of Commerce of the Lower Keys, located in the old United Services Organization (USO) building at the intersection of Southard and Whitehead streets. In Key West, approximately 150 local volunteers and medical staff – including physicians from the medical branch of the Cuban Confederation of Professionals in Exile and several nurses from a Cuban nursing home in Hialeah – worked in shifts to operate a 24-hour infirmary and processing center for incoming Marielitos which provided medical care, food and clothing. Photograph by Dale McDonald, 1980.

Bracing for the arrival of thousands more refugees, with no word on aid from the federal government, Florida Governor Bob Graham declared a state of emergency in Monroe and Dade counties on April 28.

According to a U.S. Coast Guard report, 15,761 refugees had arrived in south Florida for processing by early May. These staggering figures made clear to President Carter that the flood of immigrants could not be stemmed, prompting him to take action.

Refugees wait to be processed by U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) agents in a temporary housing center located at an old naval seaplane hangar at Trumbo Point in Key West. The centers became so clogged with refugees in need of processing that many were forced to live for weeks, and sometimes months, in nearby tent camps while awaiting approval. About half of the total Cuban entrants of the 1980 Mariel Boatlift were registered at makeshift immigration processing centers in the south Florida cities of Key West, Opa-Locka and Miami. Photograph by Dale McDonald, 1980.

A Monroe County school bus filled with Marielitos passes Trumbo Point as it heads to Naval Air Station Boca Chica, also in Key West, to await final transfer at a processing center in Miami.

Mariel-era Immigration Policy

On May 6, Carter officially declared a state of emergency in the areas of Florida most “severely affected” by the influx of Cubans and Haitians. He also announced an open-arms policy in response to the boatlift which would “provide an open heart and open arms to refugees seeking freedom from Communist domination.” The next month, on June 20, the Cuban-Haitian Entrant Program was established, whereby Haitians that arrived during the Mariel-era (ending on October 10, 1980) would receive the same temporary status as Cubans and both groups would have access to the same rights as refugees.

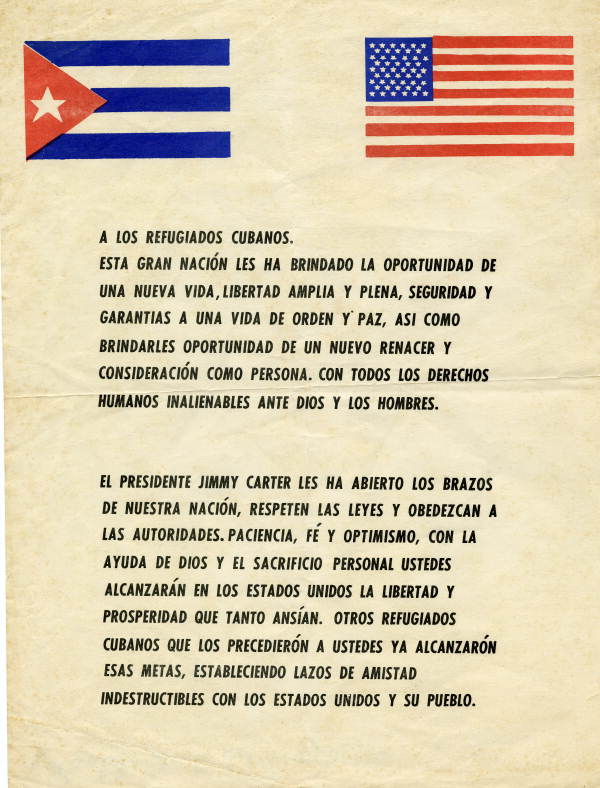

Flier circulated on behalf of President Carter to Cuban refugees arriving in the United States during the Mariel Boatlift. Translation: “To the Cuban refugees: …President Jimmy Carter has opened the arms of our nation, respect the laws and obey the authorities.” Click to enlarge and read full translation.

In light of the open-arms policy, Castro called for the forced deportation of convicted criminals, the mentally ill, homosexuals and prostitutes. In an effort to halt the entry of such individuals, Carter called for a blockade of the flotilla and deployed members of the U.S. Coast Guard to seize incoming boats.

Aerial view of impounded vessels seized by the U.S. Coast Guard during the Mariel Boatlift Blockade. Photograph by Dale McDonald, 1980.

While guards did take possession of at least 1,400 boats, numerous others slipped by and a stream of 100,000 more Cuban and Haitian refugees continued to pour into Florida over the next five months.

Florida Marine Patrol officer monitors the Florida Straits as boats arrive with refugees. After the U.S. Customs Office announced its intention to arrest any private boaters attempting to charge Marielitos for their travel, Florida Marine Patrol officers were sent to ensure that all refugees disembarked at designated locations and were not simply dropped ashore.

After the high volume of entrants had inundated the immigration processing centers already set up in south Florida, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) opened refugee resettlement camps at Eglin Air Force Base in northern Florida; Ft. McCoy in Wisconsin; Ft. Chaffee in Arkansas; and Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania. These alternative centers ultimately processed and resettled 62,000 new immigrants, but the time-intensive vetting process required refugees to wait at the camps for weeks, sometimes months.

In Ft. Chaffee, after a group of entrants grew frustrated with their uncertain status in the resettlement camp, a riot broke out in June 1980. Riots also occurred at the Eglin facility and at a federal penitentiary in Atlanta. These incidences bolstered existing rumors that Castro had unleashed Cuba’s criminal and mentally ill populations on the United States. Popular films such as Scarface (1983) helped perpetuate this stereotype. However, academic studies of Marielitos proved these rumors to be exaggerated. In fact, only 4 percent of Marielitos had criminal records, and of these, many had been imprisoned for political reasons. Over 2,000 entrants were jailed or detained upon arriving in Florida during the exodus. Some were deported back to Cuba, but many remained imprisoned for several years after the boatlift ended.

The Mariel Boatlift ended by mutual agreement between the United States and Cuba in October 1980.

In 1984, the Mariel refugees from Cuba obtained permanent legal status under a revision to the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966. However, this law did not classify Haitian entrants as political refugees; Haitians were instead considered economic refugees, making them ineligible for the same residency status as Cubans and subject to immediate deportation.

Two years later, under the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, all Cuban-Haitian entrants that had immigrated during 1980 were eligible to apply for permanent residency.

The Legacy of the Mariel Boatlift

Between 60,000 and 80,000 “Mariel” Cubans resettled in south Florida. Seventy-one percent of those entrants arriving in 1980 were working-class and black or mixed-race, a departure from the disproportionately white, wealthy and educated wave of Cubans that had immigrated in the prior two decades. Though they faced initial economic and social limitations, one report found that within six years of coming to the United States, most of the 1980 Cuban entrants had found jobs, improved their income levels and carved out a niche in Miami.

The same report, however, found that Haitians who had arrived in south Florida in 1980 had diminished levels of education, English literacy and employment compared with those that had immigrated in the 1960s and 70s. They were further stigmatized as carriers of HIV and generally experienced a harder time finding work and social acceptance. As of 1986, 33 percent of Haitian males and 80 percent of Haitian females living in the Florida were unemployed, though those numbers saw steady improvement in the 1990s.

The massive influx of Cubans in 1980 forever changed Miami’s Cuban community and, in turn, Florida’s, by creating an ethnic immigrant enclave much more representative of the social, economic and racial demographics in Cuba.

Selected Sources:

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Mariel Boatlift of 1980." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332816.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Mariel Boatlift of 1980." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332816. Accessed January 24, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, October 10). The Mariel Boatlift of 1980. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332816

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program