Description of previous item

Description of next item

A Brush with the Black Death

Published April 4, 2018 by Florida Memory

If you thought bubonic plague only caused epidemics in medieval Europe, think again! Pensacola experienced an outbreak of the infamous disease in 1920 that resulted in at least seven deaths. The episode turned out to be a transitional moment for public health in the city, as local, state and federal officials took action to prevent future attacks.

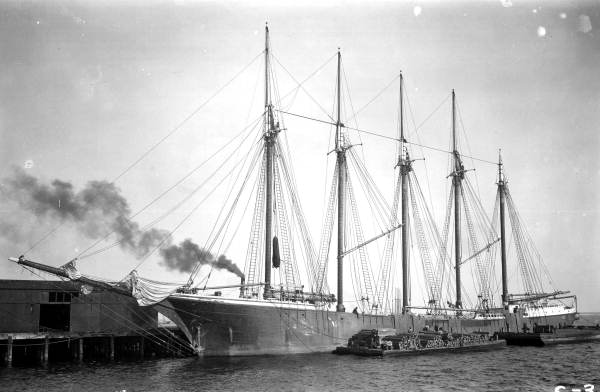

A schooner loading lumber in Pensacola Harbor, ca. 1900. Ships like this one may have been the source of the rats (and fleas) that transmitted the bubonic plague to humans during the outbreak of 1920.

Bubonic plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, typically spread by infected fleas on small rodents like mice or rats. Vaccines don’t do much to prevent the plague, but it responds well to several kinds of antibiotics. Unfortunately, those medicines were not around in the 14th century when the bubonic plague struck Europe, resulting in the deaths of somewhere between 30 and 60 percent of the population. The term “Black Death” is often used to describe this European outbreak, likely a reference to the dark lesions infected patients would develop under the skin as a result of internal bleeding. In reality, people at that time usually called the epidemic the “Big Death” or “Great Mortality.” After a series of later historians continued to use “Black Death” instead, however, the name stuck.

Bites from fleas like this one are typically responsible for transmitting the bubonic plague to humans. Image courtesy of the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

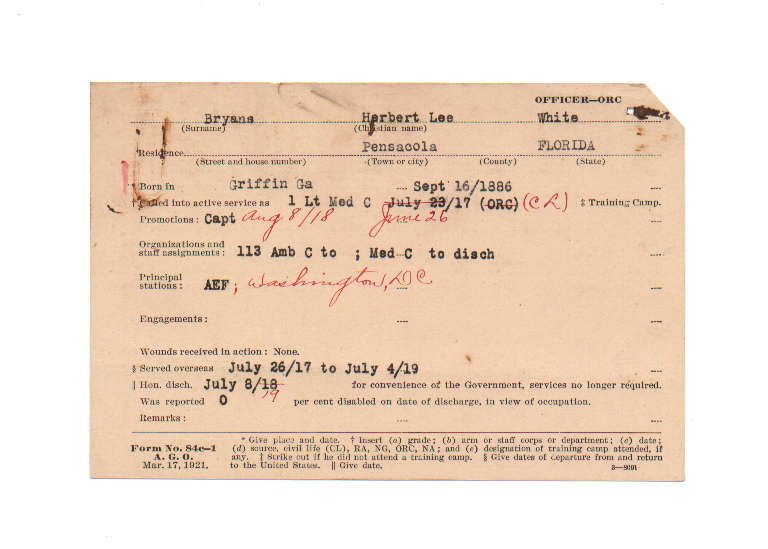

The bubonic plague didn’t die with the Middle Ages. Outbreaks have occurred in every century since the Black Death, including as recently as 2017 in Madagascar. The plague outbreak in Pensacola was discovered by local physician Dr. Herbert Lee Bryans in June 1920 when one of his patients became very suddenly ill and delirious with fever. When the patient also developed a telltale “bubo” (a swollen and darkened gland infected by plague bacteria) near his groin, Bryans suspected something unusual and contacted the state bacteriologist, Dr. Fritz Albert Brink. After personally examining the patient, Brink quickly diagnosed the disease as the bubonic plague.

The World War I service card of Dr. Herbert Lee Bryans, the physician who first sounded the alarm in the Pensacola outbreak of plague in 1920. Dr. Bryans served in the U.S. Army Medical Corps and was briefly on detached duty with the British Royal Army Medical Corps in England, Belgium and France. Click to enlarge the image.

To verify his suspicions, Brink took samples from the bubo, which he then injected into two guinea pigs. He also prepared slides to view under a microscope. All tests confirmed his original diagnosis. The guinea pigs quickly developed symptoms of plague and died, and the slides revealed bacteria consistent with Yersinia pestis.

To stop the disease from spreading further, its source needed to be identified quickly. Bryans’ patient had not left Pensacola or been aboard a ship anytime recently, which ruled out the possibility that he had brought the disease into the city from someplace else. Still, several more cases appeared in June 1920. Since the modern bubonic plague generally cannot spread from person to person, this meant the source of infection had to be the fleas infesting local rodents.

Public health officials blamed rodents like this rat for harboring the fleas that transmitted the plague bacteria to humans.

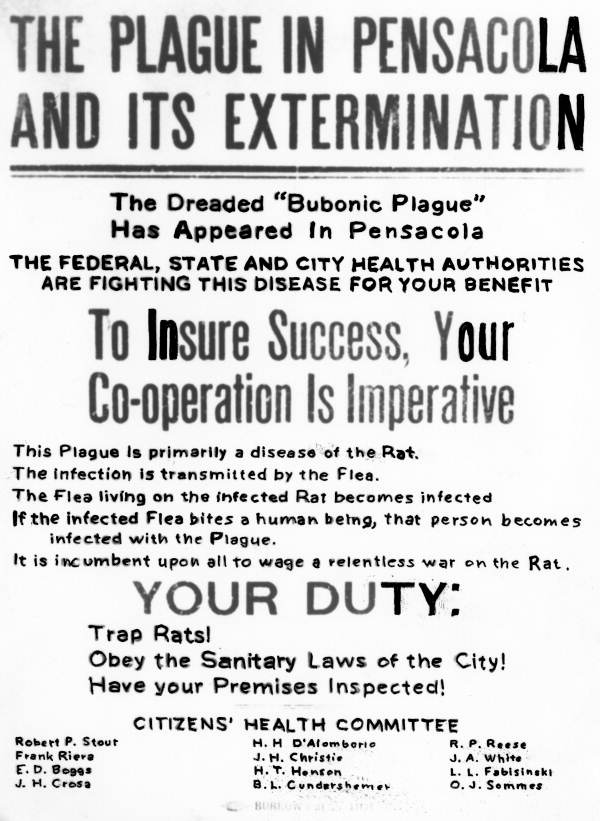

Florida’s State Board of Health sprung into action, with support from the U.S. Public Health Service. The state officials already had a laboratory in Pensacola at the corner of Palafox and Cervantes streets, which became the control center for the eradication effort. Federal health authorities also brought in Hamilton, a mobile laboratory train car, to assist. The human plague victims were isolated and those who consented were treated with serum. Out of 10 total cases, seven victims died.

Flier urging Pensacola citizens to cooperate with public health officials to help end the bubonic plague outbreak (1920). Box 1, Folder 22, Florida Health Notes Photographs (Series 917).

Meanwhile, city, state and federal authorities launched an all-out effort to eradicate the rodents responsible for harboring the infected fleas. The public health experts captured, examined and disposed of over 35,000 rats and mice from June 1920 to July 1921, carefully studying the fleas that came with them. The program’s final report gives 211 as the largest number of fleas found on a single rat, although the average was closer to about 10. City officials encouraged the public to do their share by trapping rats, covering them in oil to kill the fleas and turning them in to the public health experts for processing.

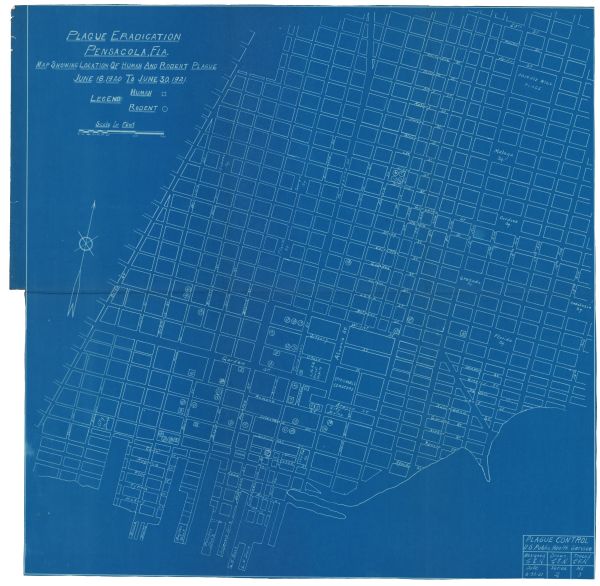

Map showing the locations of rats and humans found to be infected with bubonic plague bacteria. Both categories of infected cases are numbered in order of their discovery. Box 1, Folder 9, State Board of Health Subject Files (Series 900).

Wherever rats infected with plague bacteria were found, a team followed behind to clean up whatever conditions had made the property attractive to them. The eradication program ultimately used 1,228 pounds of cyanide and 1,854 pints of sulphuric acid to fumigate buildings. The team also demolished seven houses and hauled 280 truckloads of trash and debris to the city dumps. The city government did its part to prevent future rodent infestations by passing new ordinances requiring business owners and residents to ratproof their buildings. Plank sidewalks, which offered rats and mice a convenient space to live, were outlawed and replaced with stone, brick or concrete. Under the new laws, incoming ships had to attach rat shields to their mooring lines, and ramps and gangplanks leading from the ship to the wharf had to be taken up when not in use.

Pensacola’s brush with the bubonic plague was brief, but it still cost the city seven lives. Local citizens took the matter seriously, however, and acted quickly in ways that ultimately made Pensacola a safer, healthier place to live and work.

If you enjoyed reading about this episode in the history of Florida’s public health, check out our online exhibit, Pestilence, Potions, and Persistence: Early Florida Medicine.

Sources:

John Kelly. The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time. New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "A Brush with the Black Death." Floridiana, 2018. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332830.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "A Brush with the Black Death." Floridiana, 2018, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332830. Accessed February 12, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2018, April 4). A Brush with the Black Death. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332830

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program