Description of previous item

Description of next item

Researching State and County Officers

Published June 6, 2018 by Florida Memory

Do you have an ancestor who served in public office at the county or state level? Are you trying to determine who was sheriff or tax collector or county judge at a certain point in your county’s history? Good news! The State Archives can help you get some answers!

One of the primary responsibilities of the secretary of state (or territory prior to 1845) is to keep track of who has been officially appointed or elected to each office, both for the state and its various counties. This information is documented in several kinds of records here at the State Archives, which can come in handy if you’re researching a local history topic or the life of an ancestor who was a public servant.

To explain the kinds of records we have available and how to use them to research a specific person, let’s start with an example. Let’s say you know you have an ancestor named J.W. Applegate who lived from around the 1830s to about 1919, and you’ve always heard he was either a member of the school board or the superintendent of public instruction in Clay County, but you don’t know exactly when.

Step 1: Consult the State and County Officer Directories (Series S259 and S1284).

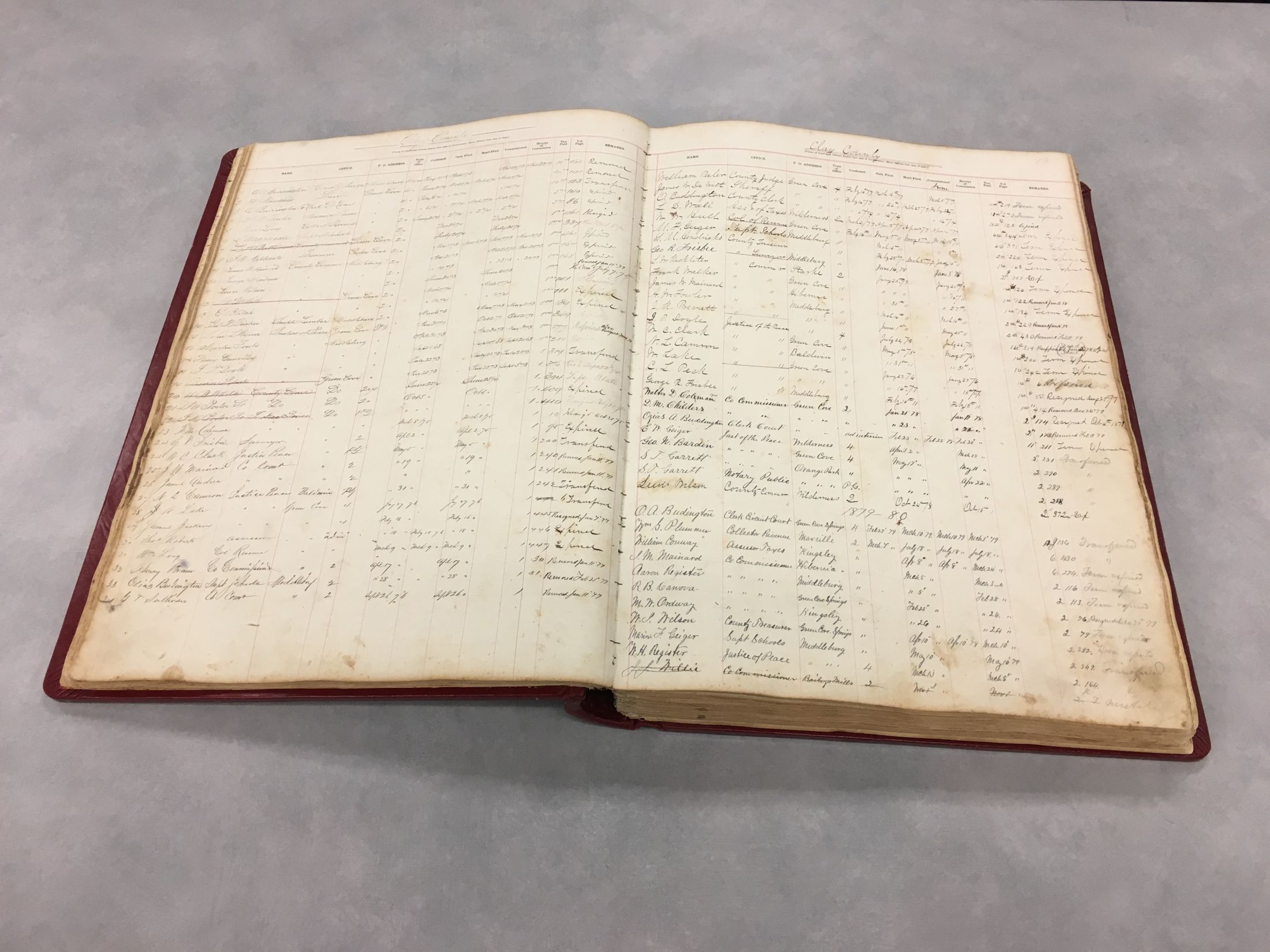

The easiest way to begin is to look for the person in the State and County Officer Directories. These are a series of bound ledgers containing lists of county and state officials. Series S259 covers the Territorial Era and the early years of Florida’s statehood, while Series S1284 runs roughly from 1845 to about 1989, overlapping slightly with Series S259. Each entry lists the officer’s name, date of commission, election or appointment, and remarks explaining how their term of office ended. Usually their term simply expired according to law, but sometimes the person resigned, died, moved away from the state or was removed from office by the governor. After about 1870, the volumes also list the person’s post office address, which can be very handy if you’re tracking down an ancestor who gave the census takers the slip! Here’s an example of what the ledgers look like:

Volume 7 of the State and County Officer Directories (Series S1284).

Returning to our example, let’s look for J.W. Applegate. The volumes in Series S259 and S1284 are arranged chronologically, so let’s look at volumes from when he was at about the right age for public service, maybe his 30s and 40s. Lo and behold! Here we find him listed in Series S1284, Volume 7, which covers the period from 1871 to 1889. It looks like he actually held more than one office during this period:

Page from Volume 7 of Series S1284 showing commission data from officers of Clay County in the 1870s. J.W. Applegate shows up with two different commissions, one as county treasurer and one as superintendent of public instruction (Click the image to enlarge).

Just from this one record, we can see that J.W. Applegate held two commissions in the 1870s, one as superintendent of public instruction and one as county treasurer. We also can see that he lived in Green Cove Springs at the time. For his commission as superintendent of public instruction, we get the date of his actual commission, as well as the day his written oath of office was filed with the Secretary of State. For his term as county treasurer, we get a little more. Since county treasurers had to be bonded, we can see the date his bond was received by the Secretary of State. In both cases, we get the length of time he was to serve, verification that he had paid his taxes, and some information about how his term ended. Applegate’s term as county treasurer expired according to law, meaning someone was elected to take his place. He resigned, however, from his position as superintendent of public instruction, and in this case we don’t get the date that occurred.

What else can we learn?

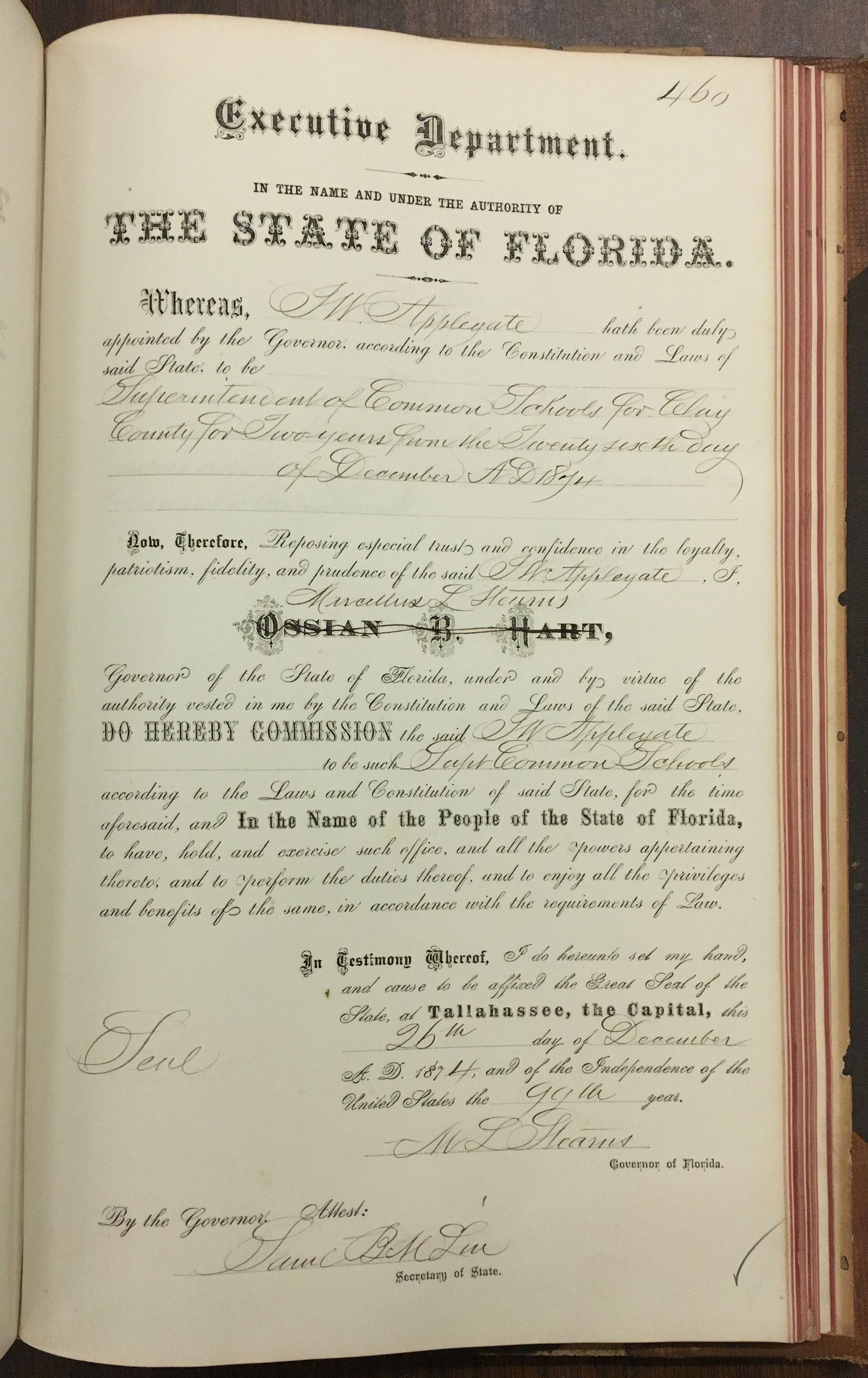

Step 2: Find the person’s commission.

In many cases, the State Archives has more than just an index entry documenting a person’s public service. We also usually have a copy of the person’s commission, their signed oath of office, and a copy of their bond if it was required by law for them to have one.

Let’s start with the commission. This is simply the governor’s official notice to a state or county officer that they are confirmed in office and can begin exercising their duties. Here’s the one J.W. Applegate received when he became superintendent of public instruction for Clay County in 1874:

J.W. Applegate’s commission as superintendent of public instruction for Clay County, in Volume 4 of the Secretary of State’s Record of Commissions (Series S1285), State Archives of Florida.

Commissions for public officers were recorded in different ways over time, so tracking one down can take some digging. Here are the catalog records for the record series where most commissions may be found:

Series S1285: Commissions for State and County Officers, 1845-1900

Series S1286: Commissions for State Appointed Officers, 1898-1964, 1969-78

Series S1287: Commissions for County Appointed Officers, 1901-1951

Series S1288: Commissions for County Elected Officers, 1898-1963, 1969-78, 1989-2004

Series S1289: Commissions for Officers Elected to Ad Interim Positions, 1906-1935

Series S1290: Commissions for Senate-Confirmed Officers, 1913-1963

Series S623: Commissions for Judges, 1935-1942

If you’re looking for a commission that falls outside these categories, contact the State Archives Reference Desk for further assistance.

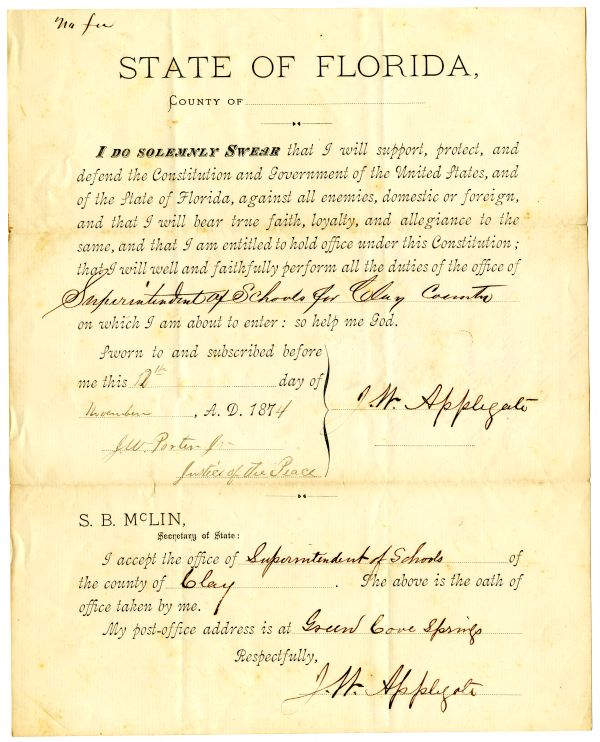

Step 3: Find the person’s oath and bond (if applicable).

All public officials typically had to sign an oath swearing to uphold the state constitution and discharge the duties of their office to the best of their ability in accordance with the law. The signed oaths were filed in the office of the secretary of state, and many are available in the State Archives’ collections. Here, for example, is the one J.W. Applegate signed after he was elected superintendent of public instruction for Clay County in 1874.

Oath of J.W. Applegate, superintendent of public instruction for Clay County (1874), in Box 3, Folder 2, Oaths and Bonds of State and County Officers (Series S622), State Archives of Florida.

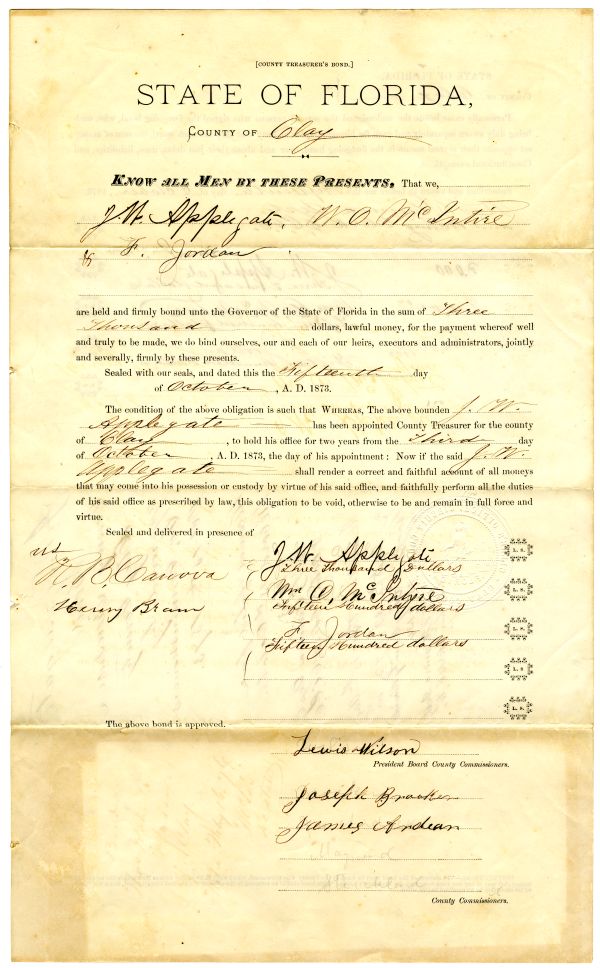

Additionally, in some cases state law required a person to be bonded if he was going to be handling money or financial transactions on behalf of the county. Applegate was not required to be bonded for his position as superintendent of public instruction, but he did need a bond to be county treasurer, and here it is:

Bond of J.W. Applegate, county treasurer – Clay County (1873) in Box 3, Folder 2, Oaths and Bonds of State and County Officers (Series S622), State Archives of Florida.

Most oaths and bonds for county and state officers between 1845 and the mid-20th century are found in Series S622, with a few exceptions. Oaths and bonds for notaries who held office between 1845 and 1897, for example, are in Series S16.

Step 4: Check for related documentation about the person’s service.

While the county courthouse is your best bet for finding records relating to the work a person did while serving in a county office, the State Archives sometimes has a few additional helpful documents. In J.W. Applegate’s case, for example, we see from his entry in the State and County Officer Directory that he resigned his post as superintendent of public instruction, although we’re not given a date. Sometimes we can get a few clues as to why a person may have resigned from their position by determining the date of the resignation and checking to see if their letter of resignation to the governor has survived.

There are two main ways to find out when a person resigned from a county or state office. One is to look at the State and County Officer Directory and see if the secretary of state’s office made a note in the “Remarks” column dating the event. In Applegate’s case, we only get the fact he resigned. The second method is to look for the governor’s acceptance of the resignation. Luckily, governors from 1868 to 1975 kept track of all the resignations they accepted in a single set of volumes contained in Series S260. The 10 handwritten volumes in the series are essentially in chronological order and many have indexes.

Those records can tell us when a person resigned, but what about why? For that information, the best source is the officer’s own explanation in a letter of resignation. Resignation letters can be found in one of several places depending on the time period. For mid-to-late 19th century cases like our friend J.W. Applegate, the best place to start is Series S1326, which includes letters of resignation written to the governor and filed by the secretary of state, as well as notices from the governor that he had removed an official by executive authority. This series is far from exhaustive, but it contains some interesting insights into 19th century politics and the lives of public servants from that era, which we explored in a recent post titled ‘I Quit!!!’ In the case of Mr. Applegate, no letter of resignation was available to document his decision to quit the role of superintendent of public instruction, but there is a letter from the governor announcing his decision to remove Applegate from his other job as county treasurer:

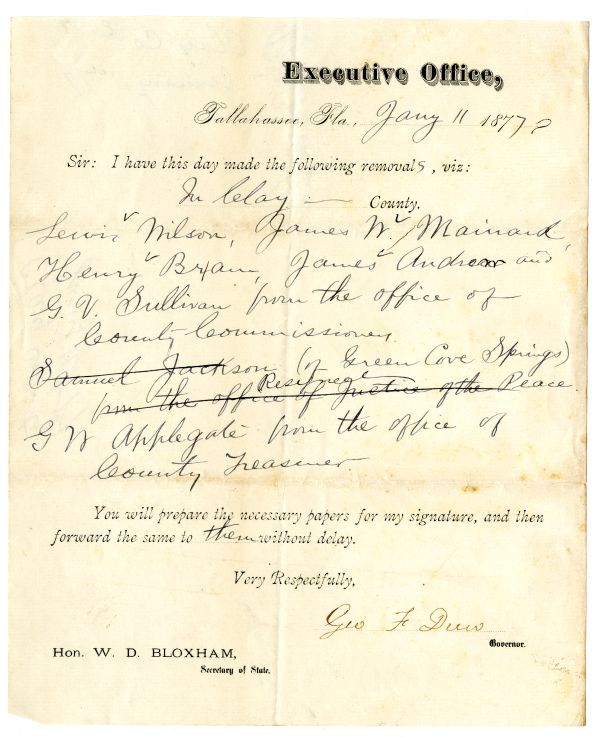

Letter from Governor George Franklin Drew to Secretary of State William D. Bloxham announcing several removals from office for Clay County (January 11, 1877). Found in Box 1, folder 3 of Resignations and Removals (Series S1326), State Archives of Florida.

Even though this document doesn’t give us a clear reason for Applegate’s departure from either the office of county treasurer or superintendent of public instruction, we can use a little historical context to make an educated guess. Notice the date of this removal notice from Governor Drew – January 11, 1877. Drew had just been voted into office as the first Democrat to serve as governor since the end of the Civil War. Applegate, as well as everyone else named in the letter, had been appointed by Drew’s Republican predecessors during Reconstruction. The political divide between the two major parties was acrimonious during this period, and upon taking office Drew took every opportunity he could to remove his political opponents from power. This caused, as you can imagine, a considerable amount of paperwork in the form of removal notices and new commissions, oaths and bonds, which are well documented in the State Archives collections. Considering J.W. Applegate was removed at the same time as the entire Clay County Board of Commissioners right after Drew took office, he was almost certainly part of this purge. Additional research in the papers of Governor Drew or local sources in Clay County would help verify this hypothesis.

Researching in These Records

The records described in this blog are all open for public research here at the State Archives, or you can contact the State Archives Reference Desk to verify an officer’s dates of service or get copies of their commission, oath, or bond if it has survived. When you call or email, make sure you include the person’s full name, the county they served in, the office you think they served in, and as close as possible to the dates they would have served. If you aren’t sure about the dates, have the person’s birth and death dates ready – that will at least narrow down the search. Consult the State Archives’ fee schedule to find out the cost of receiving copies or scans.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Researching State and County Officers." Floridiana, 2018. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/333285.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Researching State and County Officers." Floridiana, 2018, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/333285. Accessed March 14, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2018, June 6). Researching State and County Officers. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/333285

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program