Florida Memory is administered by the Florida Department of State, Division of Library and Information Services, Bureau of Archives and Records Management. The digitized records on Florida Memory come from the collections of the State Archives of Florida and the special collections of the State Library of Florida.

State Archives of Florida

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- State Archives Online Catalog

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- ArchivesFlorida.com

State Library of Florida

Related Sites

Description of previous item

Description of next item

Source

Description

Date

Contributors

Format

Coverage

Topic

Subjects

African American universities and colleges

African American women

African Americans -- Biography

Avery Normal Institute

Barber-Scotia College

Bernes, Miss

Bethune, Albertus

Bethune, Alert M., Jr.

Bethune, Alert M., Sr.

Bethune-Cookman College (Daytona Beach, Fla.)

Bomer, Hattie

Bowen, Irene Smallwood

Cantey, Rebecca

Cathcart, Miss

Chrisman, Mary

Daytona Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls (Daytona Beach, Fla.)

Gamble, James Norris, 1836-1932

Garner, George Robert, III, 1892-1971

Haines Normal and Industrial Institute

Harrison, Estelle Roberts

James, A. L.

Laney, Lucy Craft, 1854-1933

Lyons, Judson Whitlocke, 1860?-1924

McLeod family (Mayesville, S.C.)

McLeod, Beauregard

McLeod, Carrie

McLeod, Cecelia

McLeod, Hattie Bell

McLeod, Julia

McLeod, Kelly

McLeod, Kissie

McLeod, Magdalena

McLeod, Monday

McLeod, Patsy McIntosh

McLeod, Rebecca

McLeod, Sally

McLeod, Samuel

McLeod, Samuel, Jr.

McLeod, Satira

McLeod, William Thomas

Miller, M. D.

Miller, M. D., Mrs.

Moody Bible Institute

National Council of Negro Women

Pius XI, Pope, 1857-1939

Poro College

Procter & Gamble Company

Roosevelt, Eleanor, 1884-1962

Shankle, Janie

Simmons, Mr.

Washington, Booker T., 1856-1915

Watkins, C. J.

Webb, E. A.

Webb, E. A., Mrs.

White Sewing Machine Company

White, Thomas Howard

Williams, John

Williams, Wilberforce

Wilson, Ben

Wilson, Emma

Geographic Term

General Note

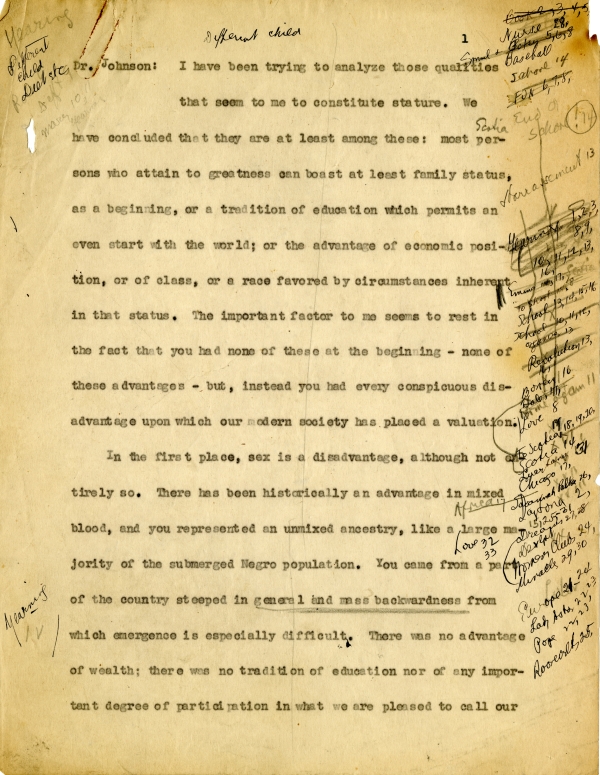

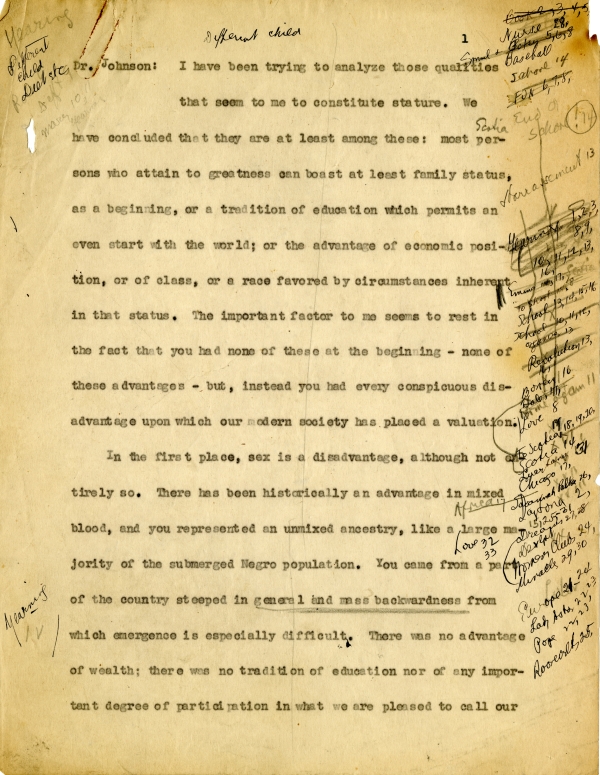

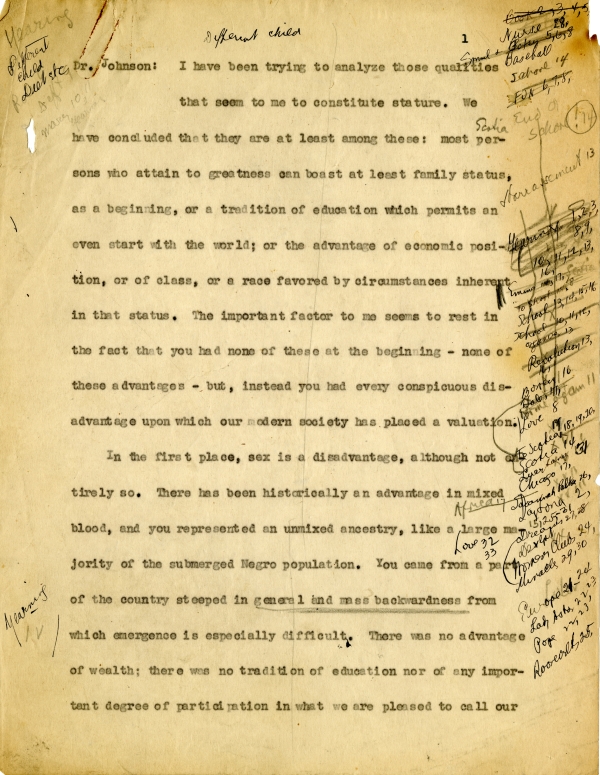

Dr. Johnson: I have been trying to analyze those qualities that seem to me to constitute stature.

We have concluded that they are at least among these: most persons who attain to greatness can boast at least family status, as a beginning, or a tradition of education which permits an even start with the world: or the advantage of economic position, or of class, or a race favored by circumstances inherent in that status.

The important factor to me seems to rest in the fact that you had none of these at the beginning – none of these advantages – but, instead you had every conspicuous disadvantage upon which our modern society has placed a valuation.

In the first place, sex is a disadvantage, although not entirely so. There has been historically an advantage in mixed blood, and you represent an unmixed ancestry, like a large majority of the submerged Negro population. You came from a part of the country steeped in general and mass backwardness from which emergence is especially difficult. There was no advantage of wealth; there was no tradition of education nor of any important degree of participation in what we are pleased to call our American civilization.

Dr. Johnson: I have been trying to analyze those qualities that seem to me to constitute stature.

We have concluded that they are at least among these: most persons who attain to greatness can boast at least family status, as a beginning, or a tradition of education which permits an even start with the world: or the advantage of economic position, or of class, or a race favored by circumstances inherent in that status.

The important factor to me seems to rest in the fact that you had none of these at the beginning – none of these advantages – but, instead you had every conspicuous disadvantage upon which our modern society has placed a valuation.

In the first place, sex is a disadvantage, although not entirely so. There has been historically an advantage in mixed blood, and you represent an unmixed ancestry, like a large majority of the submerged Negro population. You came from a part of the country steeped in general and mass backwardness from which emergence is especially difficult. There was no advantage of wealth; there was no tradition of education nor of any important degree of participation in what we are pleased to call our

Title

Subject

Description

Creator

Source

Date

Contributor

Format

Language

Type

Identifier

Coverage

Geographic Term

Thumbnail

Display Date

ImageID

topic

Subject - Corporate

Subject - Person

Transcript

Dr. Johnson: I have been trying to analyze those qualities that seem to me to constitute stature.

We have concluded that they are at least among these: most persons who attain to greatness can boast at least family status, as a beginning, or a tradition of education which permits an even start with the world: or the advantage of economic position, or of class, or a race favored by circumstances inherent in that status.

The important factor to me seems to rest in the fact that you had none of these at the beginning – none of these advantages – but, instead you had every conspicuous disadvantage upon which our modern society has placed a valuation.

In the first place, sex is a disadvantage, although not entirely so. There has been historically an advantage in mixed blood, and you represent an unmixed ancestry, like a large majority of the submerged Negro population. You came from a part of the country steeped in general and mass backwardness from which emergence is especially difficult. There was no advantage of wealth; there was no tradition of education nor of any important degree of participation in what we are pleased to call our American civilization.

Dr. Johnson: I have been trying to analyze those qualities that seem to me to constitute stature.

We have concluded that they are at least among these: most persons who attain to greatness can boast at least family status, as a beginning, or a tradition of education which permits an even start with the world: or the advantage of economic position, or of class, or a race favored by circumstances inherent in that status.

The important factor to me seems to rest in the fact that you had none of these at the beginning – none of these advantages – but, instead you had every conspicuous disadvantage upon which our modern society has placed a valuation.

In the first place, sex is a disadvantage, although not entirely so. There has been historically an advantage in mixed blood, and you represent an unmixed ancestry, like a large majority of the submerged Negro population. You came from a part of the country steeped in general and mass backwardness from which emergence is especially difficult. There was no advantage of wealth; there was no tradition of education nor of any important degree of participation in what we are pleased to call our

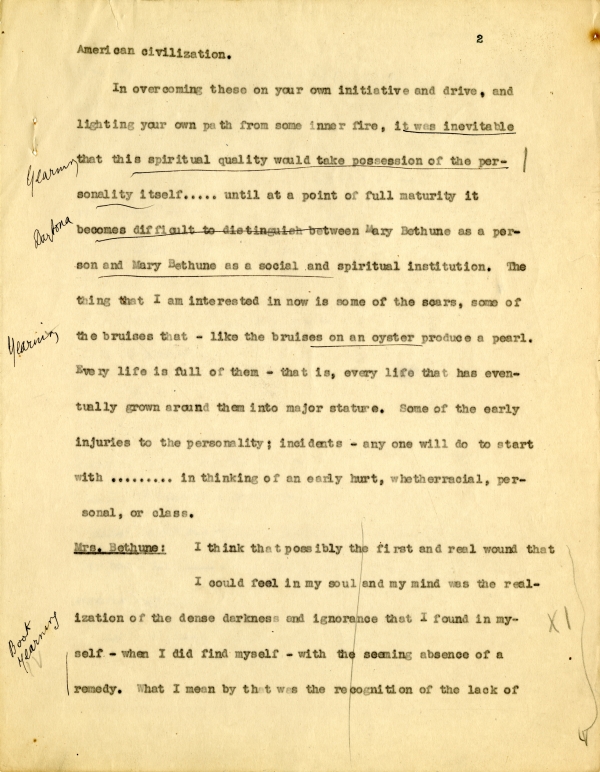

American civilization.

In overcoming these on your own initiative and drive, and lighting your own path from some inner fire, it was inevitable that this spiritual quality would take possession of the personality itself….. until at a point of full maturity it becomes difficult to distinguish between Mary Bethune as a person and Mary Bethune as a social and spiritual institution.

The thing that I am interested in now is some of the scars, some of the bruises that – like the bruises on an oyster produce a pearl.

Every life is full of them – that is, every life that has eventually grown around them into major stature. Some of the early injuries to the personality: incidents – any one will do to start with………in thinking of an early hurt, whether racial, personal, or class.

Mrs. Bethune: I think that possibly the first and real wound that I could feel in my soul and my mind was the realization of the dense darkness and ignorance that I found in myself – when I did find myself – with the seeming absence of a remedy. What I mean by that was the recognition of the lack of

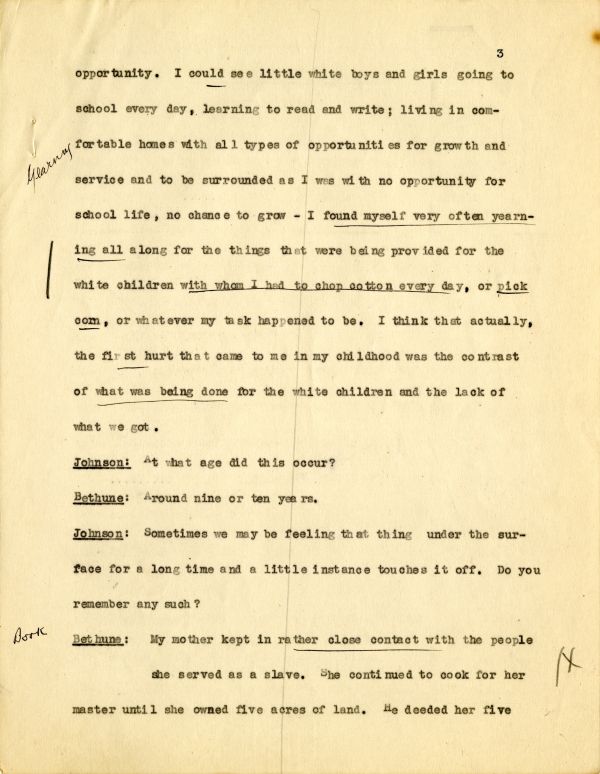

opportunity. I could see little white boys and girls going to school every day, learning to read and write; living in comfortable homes with all types of opportunities for growth and service and to be surrounded as I was with no opportunity for school life, no chance to grow – I found myself very often yearning all along for the things that were being provided for the white children with whom I had to chop cotton every day, or pick corn, or whatever my task happened to be.

I think that actually, the first hurt that came to me in my childhood was the contrast of what was being done for the white children and the lack of what we got.

Johnson: At what age did this occur?

Bethune: Around nine or ten years.

Johnson: Sometimes we may be feeling that thing under the surface for a long time and a little instance touches it off. Do you remember any such?

Bethune: My mother kept in rather close contact with the people she served as a slave. She continued to cook for her master until she owned five acres of land. He deeded her five

acres. The cabin, my father and brothers built. It was the cabin in which I was born.

She kept up these relations. Very often I was taken along after I was old enough, and on one of these occasions I remember my mother went over to do some special work for this family of Wilsons, and I was with her. I went out into what they called their play house in the yard where they did their studying. They had pencils, slates, magazines and books.

I picked up one of the books . . . . and one of the girls said to me – "You can't read that – put that down. I will show you some pictures over here," and when she said to me "You can't read that– put that down" it just did something to my pride and to my heart that made me feel that some day I would read just as she was reading.

I did put it down, and followed her lead and looked at the picture book that she had. But I went away from there determined to learn how to read and that some day I would master for myself just what they were getting and it was that aim that I followed.

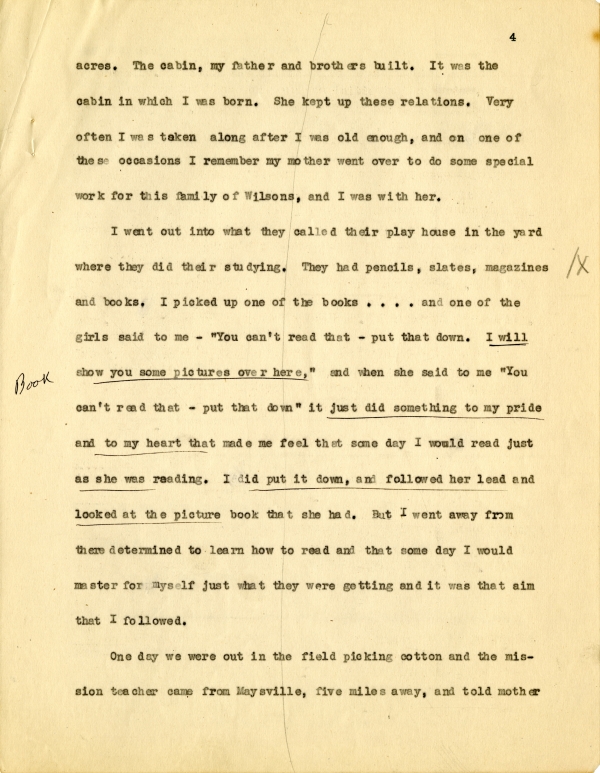

One day we were out in the field picking cotton and the mission teacher came from Maysville, five miles away, and told mother

and father that the Presbyterian church had established a mission where the Negro children could go and that the children would be allowed to go. I was among the first of the young ones to enroll, and …. so it seemed to me.

That first morning on my way to school I kept the thought uppermost "Put that down – you can't read," and I felt that I was on my way to read and it was one of the incentives that fired me in my determination to read. And I think that because of that I grasped my lessons and my words better than the average child and it was not long before I was able to read and write.

Johnson: What was the attitude of your mother? Or, did you tell her about it?

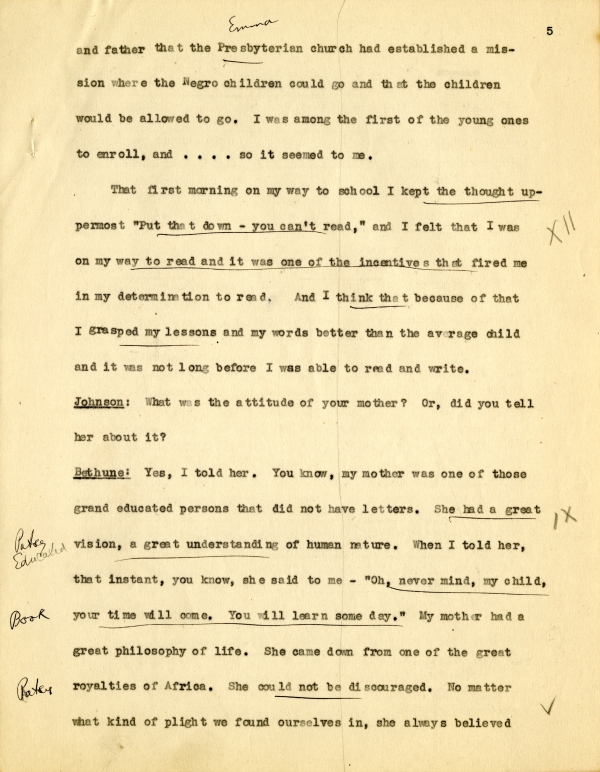

Bethune: Yes, I told her. You know, my mother was one of those grand educated persons that did not have letters. She had a great vision, a great understanding of human nature. When I told her, that instant, you know, she said to me – "Oh, never mind, my child, your time will come. You will learn some day."

My mother had a great philosophy of life. She came down from one of the great royalties of Africa. She could not be discouraged. No matter what kind of plight we found ourselves in, she always believed

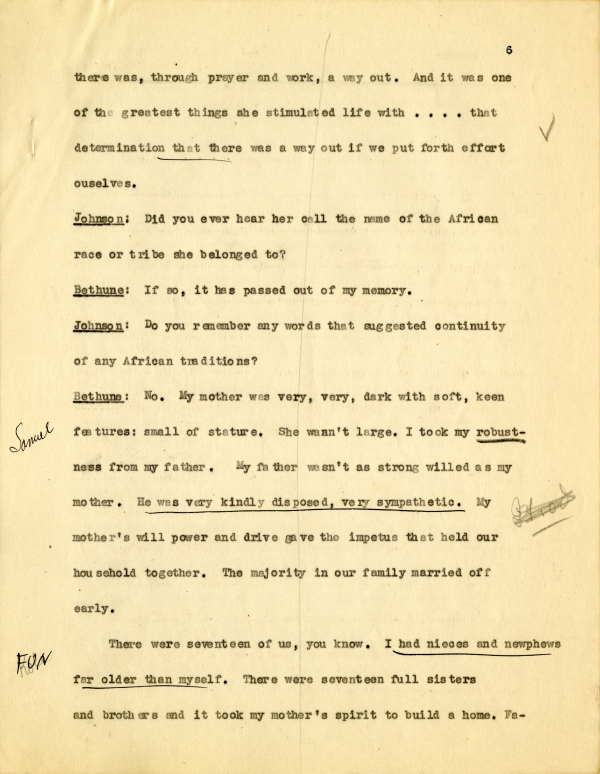

there was, through prayer and work, a way out. And it was one of the greatest things she stimulated life with….that determination that there was a way out if we put forth effort ourselves.

Johnson: Did you ever hear her call the name of the African race of tribe she belonged to?

Bethune: If so, it has passed out of my memory.

Johnson: Do you remember any words that suggested continuity of any African tradition?

Bethune: No. My mother was very, very, dark with soft, keen features: small of stature. She wasn't large. I took my robustness from my father. My father wasn't as strong willed as my mother. He was very kindly disposed, very sympathetic. My mother's will power and drive gave the impetus that held our household together. The majority in our family married off early.

There were seventeen of us, you know. I had nieces and nephews far older than myself. There were seventeen full sisters and brothers and it took my mother's spirit to build a home.

Fa-

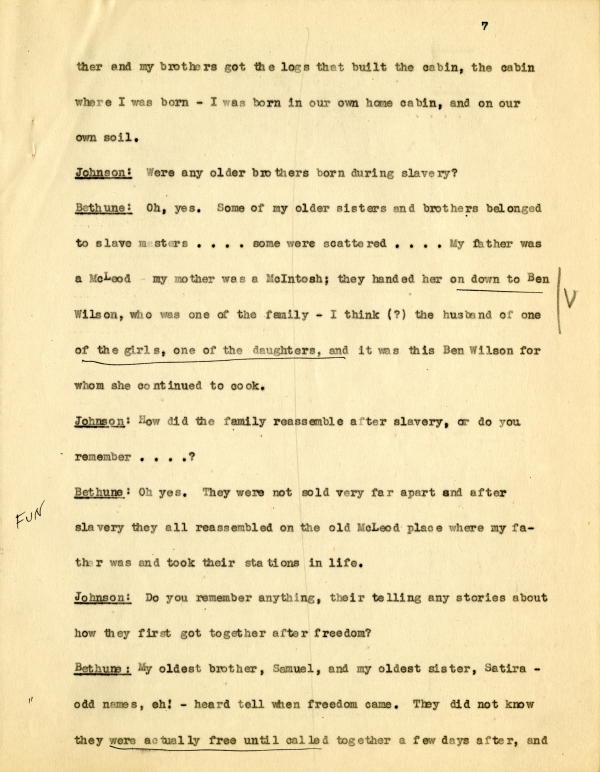

ther and my brothers got the logs that built the cabin, the cabin where I was born – I was born in our own home cabin, and on our own soil.

Johnson: Were any older brothers born during slavery?

Bethune: Oh, yes. Some of my older sisters and brothers belonged to slave masters….some were scattered….

My father was a McLeod – my mother was a McIntosh; they handed her on down to Ben Wilson who was one of the family – I think (?) the husband of one of the girls, one of the daughters, and it was this Ben Wilson for whom she continued to cook.

Johnson: How did the family reassemble after slavery, or do you remember.…?

Bethune: Oh, yes. They were not sold very far apart and after slavery they all reassembled on the old McLeod place where my father was and took their stations in life.

Johnson: Do you remember anything, their telling any stories about how the first got together after freedom?

Bethune: My oldest brother Samuel, and my oldest sister, Satira – odd names, eh! – heard tell when freedom came. They did not know they were actually free until called together a few days after, and

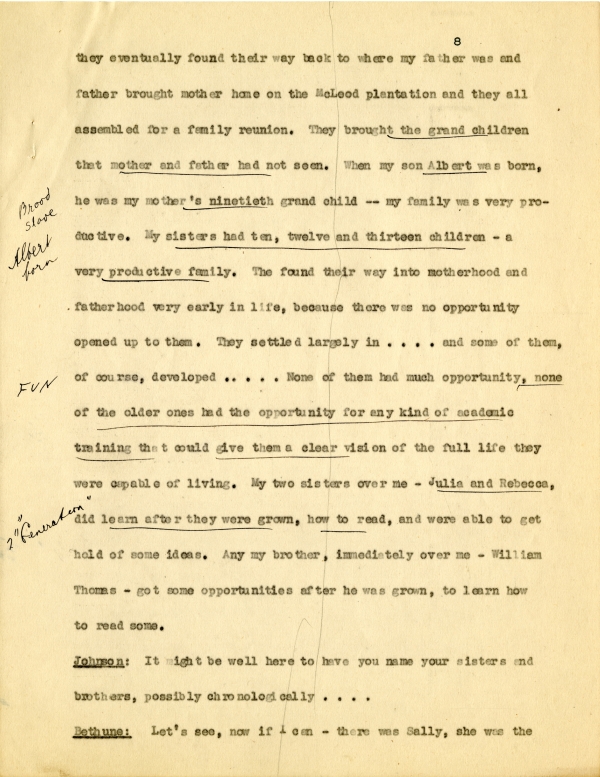

they eventually found their way back to where my father was and father brought mother home on the McLeod plantation and they all assembled for a family reunion. They brought the grand children that mother and father had not seen.

When my son Albert was born, he was my mother's ninetieth grand child – my family was very productive. My sisters had ten, twelve and thirteen children – a very productive family. They found their way into motherhood and fatherhood very early in life, because there was no opportunity opened up to them. They settled largely in …. And some of them, of course developed….

None of them had much opportunity, none of the older ones had the opportunity for any kind of academic training that could give them a clear vision of the full life they were capable of living. My two sisters over me – Julia and Rebecca, did learn after they were grown, how to read, and were able to get hold of some ideas. And my brother, immediately over me – William Thomas – got some opportunities after he was grown, to learn to read some.

Johnson: It might be well here to have you name your sisters and brothers, possibly chronologically….

Bethune: Let's see, now if I can – there was Sally, she was the

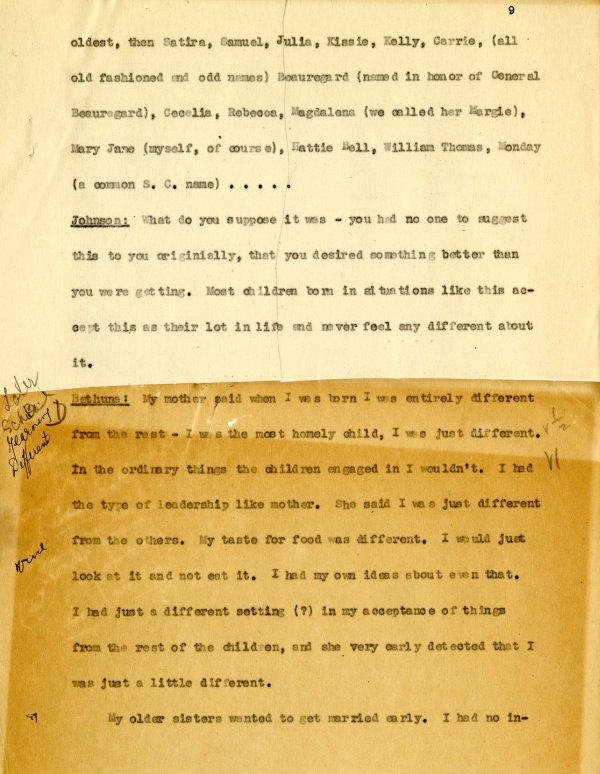

oldest, then Satira, Samuel, Julia, Kissie, Kelly, Carrie, (all old fashioned and odd names) Beauregard (named in honor of General Beauregard), Cecelia, Rebecca, Magdalena (we called her Margie), Mary Jane (myself, of course), Mattie Bell, William Thomas, Monday (a common S.C. name)….

Johnson: What do you suppose it was – you had no one to suggest this to you originally that you desired something better than you were getting. Most children born in situations like this accept this as their lot in life and never feel any different about it.

Bethune: My mother said when I was born I was entirely different from the rest – I was the most homely child, I was just different. In the ordinary things the children engaged in I wouldn't. I had the type of leadership like my mother. She said I was just different from the others.

My taste for food was different. I would just look at it and not eat it. I had my own ideas about even that. I had just a different setting (?) in my acceptance of things from the rest of the children, and she very early detected that I was just a little different. My older sisters wanted to get married early. I had no in-

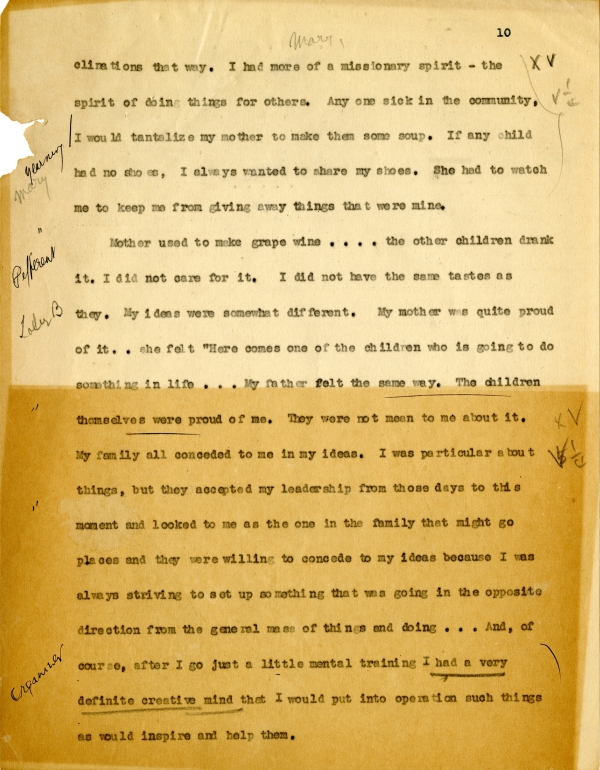

clinations that way. I had more of a missionary spirit – the spirit of doing things for others.

Any one sick in the community, I would tantalize my mother to make them some soup. If any child had no shoes, I always wanted to share my shoes. She had to watch me to keep me from giving away things that were mine.

Mother used to make grape wine….the other children drank it. I did not care for it. I did not have the same tastes as they. My ideas were somewhat different. My mother was quite proud of it..she felt "Here comes one of the children who is going to do something in life… My father felt the same way. The children themselves were proud of me. They were not mean to me about it. My family all conceded to me in my ideas.

I was particular about things, but they accepted my leadership from those days to this moment and looked to me as the one in the family that might go places and they were willing to concede to my ideas because I was always striving to set up something that was going in the opposite direction from the general mass of things and doing… And, of course, after I got just a little mental training I had a very definite creative mind that I would put into operation such things as would inspire and help them.

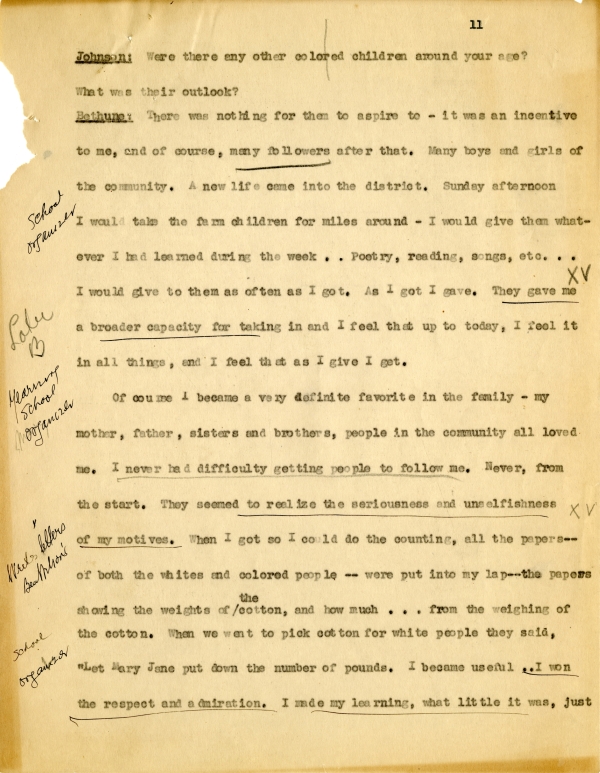

Johnson: Were there any other colored children around your age? What was their outlook?

Bethune: There was nothing for them to aspire to – it was an incentive to me, and of course, many followers after that. Many boys and girls of the community. A new life came into the district.

Sunday afternoon I would take the farm children for miles around – I would give them whatever I had learned during the week..Poetry, reading, songs, etc…I would give to them as often as I got. As I got I gave. They gave me a broader capacity for taking in and I feel that up to today, I feel it in all things, and I feel that as I give I get.

Of course I became a very definite favorite in the family – my mother, father, sisters and brothers, people in the community all loved me. I never had difficulty getting people to follow me. Never, from the start. They seemed to realize the seriousness and unselfishness of my motives.

When I got so I could do the counting, all the papers—of both the whites and colored people—were put into my lap—the papers showing the weights of the cotton, and how much…from the weighing of the cotton. When we went to pick cotton for white people they said, "Let Mary Jane put down the number of pounds."

I became useful..I won the respect and admiration. I made my learning, what little it was, just

from the beginning, spell service and cooperation, rather than something that would put me above the people around me.

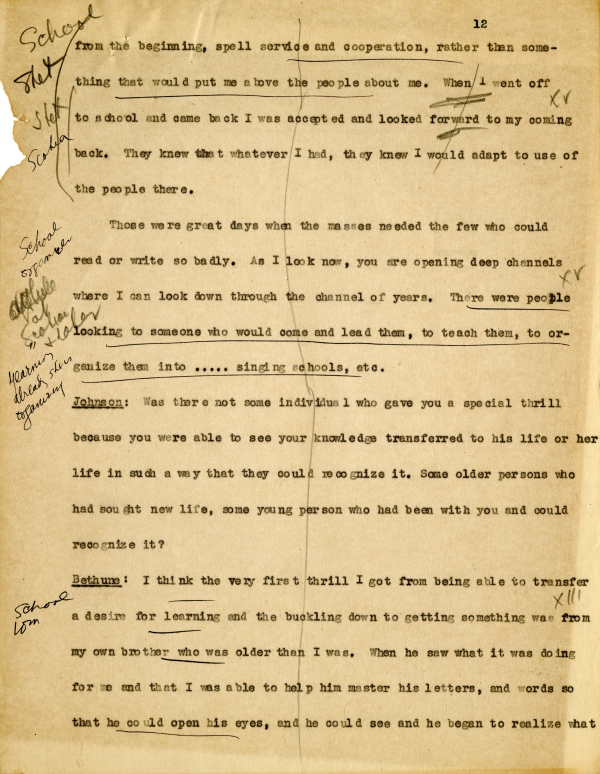

When I went off to school and came back I was accepted and looked forward to my coming back. They knew that whatever I had, they knew I would adapt to use of the people there. Those were great days when the masses needed the few who could read or write so badly.

As I look now, you are opening deep channels where I can look down through the channel of years. There were people looking to someone who would come and lead them, to teach them, to organize them into….. singing schools, etc.

Johnson: Was there not some individual who gave you a special thrill because you were able to see your knowledge transferred to his life or her life in such a way that they could recognize it. Some older persons who had sought new life, some young person who had been with you and could recognize it?

Bethune: I think the very first thrill I got from being able to transfer a desire for learning and the buckling down to getting something was from my own brother who was older than I was.

When he saw what it was doing for me and that I was able to help him master his letters, and words do that he could open his eyes, and he could see and he began to realize what

it meant to get some learning and to, himself, be awakened to such extent as to go ten miles at night to the Maysville village and attend night school until all could read, write and apply himself.

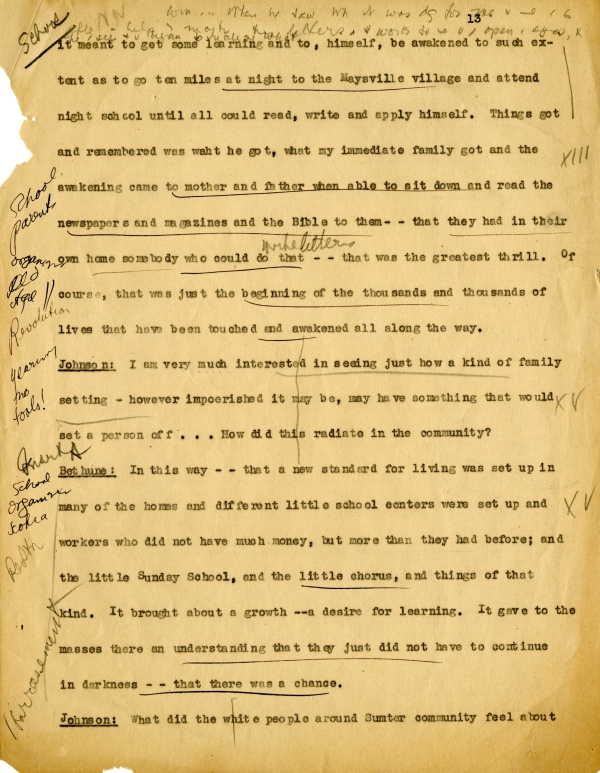

Things got and remembered was what he got, what my immediate family got and the awakening came to mother and father when able to sit down and read the newspapers and magazines and the Bible to them — that they had in their own home somebody who could do that — that was the greatest thrill.

Of course, that was just the beginning of the thousands and thousands of lives that have been touched and awakened all along the way.

Johnson: I am very much interested in seeing just how a kind of family setting – however impoverished it may be, may have something that would set a person off…How did this radiate in the community?

Bethune: In this way – that a new standard for living was set up in many of the homes and different little school centers were set up and workers who did not have much money, but more than they had before; and the little Sunday School, and the little chorus, and things of that kind. It brought about a growth – a desire for learning. It gave to the masses there an understanding that they just did not have to continue in darkness – that there was a chance.

Johnson: What did the white people around Sumter community feel about

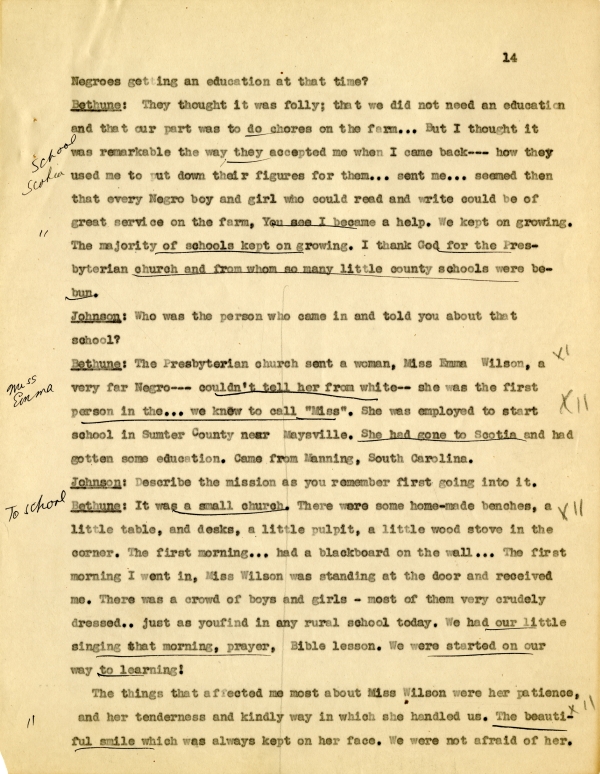

Negroes getting an education at that time?

Bethune: They thought it was folly; that we did not need an education and that our part was to do chores on the farm. But I thought it was remarkable the way they accepted me when I came back – how they used me to put down their figures for them… sent me… seemed then that every Negro boy and girl who could read and write could be of great service on the farm. You see I became a help.

We kept on growing. The majority of schools kept on growing. I thank God for the Presbyterian church and from whom so many little county school were begun.

Johnson: Who was the person who came and told you about that school?

Bethune: The Presbyterian church sent a woman, Miss Emma Wilson, a very fa[i]r Negro---couldn't tell her from white—she was the first person in the…we knew to call "Miss".

She was employed to start school in Sumter County near Maysville. She had gone to Scotia and had gotten some education. Came from Manning, South Carolina.

Johnson: Describe the mission as you remember first going into it.

Bethune: It was a small church. There were some home-made benches, a little table, and desks, a little pulpit, a little wood stove in the corner.

The first morning…had a blackboard on the wall…The first morning I went in, Miss Wilson was standing at the door and received me. There was a crowd of boys and girls – most of them very crudely dressed.. just as you find in any rural school today. We had our little singing that morning, prayer, Bible lesson. We were started on our way to learning.

The things that affected me most about Miss Wilson were her patience, and her tenderness and kindly way in which she handled us. The beautiful smile which was always kept on her face. We were not afraid of her.

We could approach her at any time.

Johnson: What was the length of time for which she contacted your life?

Bethune: She remained there continuously after that.

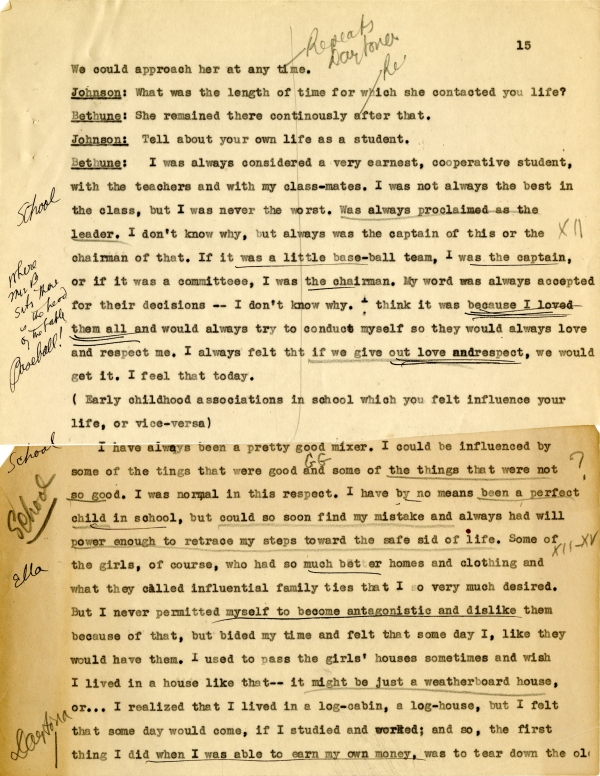

Johnson: Tell about your own life as a student.

Bethune: I was always considered a very earnest, cooperative student, with the teachers and with my class-mates. I was not always the best in the class, but I was never the worst. Was always proclaimed as the leader. I don't know why, but always was the captain of this or the chairman of that. If it was a little base-ball team, I was the captain, or if it was a committee, I was the chairman.

My word was always accepted for their decisions – I don't know why. I think it was because I loved them all and would always try to conduct myself so they would always love and respect me. I always felt that if we gave out love and respect, we would get it. I feel that today.

(Early childhood associations in school which you felt influence your life or vice-versa.)

I have always been a pretty good mixer. I could be influenced by some of the things that were good and some of the things that were not so good. I was normal in this respect. I have by no means been a perfect child in school, but could so soon find my mistake and always had will power enough to retrace my steps toward the safe side of life.

Some of the girls, of course who had so much better homes and clothing and what they called influential family ties that I so very much desired. But I never permitted myself to become antagonistic and dislike them because of that, but bided my time and felt that some day I, like they would have them.

I used to pass the girls' houses sometimes and wish I lived in a house like that—it might be just a weatherboard house, or… I realized that I lived in a log-cabin, a log-house, but I felt that some day would come, if I studied and worked; and so, the first thing I did when I was able to earn my own money, was to tear down the old

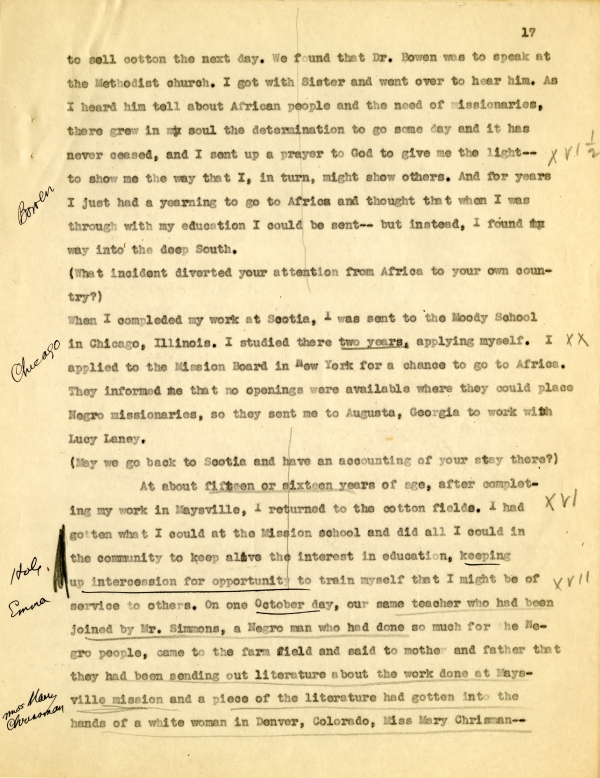

to sell cotton the next day. We found that Dr. Bowen was to speak at the Methodist church. I got with Sister and went over to hear him. As I heard him tell about African people and the need of missionaries, there grew in my soul the determination to go some day and it has never ceased, and I sent up a prayer to God to give me the light—to show me the way that I, in turn, might show others. And for years I just had a yearning to go to Africa and thought that when I was through with my education I could be sent—but instead, I found my way into the deep South.

(What incident diverted your attention from Africa to your own country?)

When I completed my work at Scotia, I was sent to the Moody School in Chicago, Illinois. I studied there two years, applying myself. I applied to the Mission Board in New York for a chance to go to Africa. They informed me that no openings were available where they could place Negro missionaries, so they sent me to Augusta, Georgia to work with Lucy Laney.

(May we go back to Scotia and have an account of your stay there?)

At about fifteen or sixteen years of age, after completing my work in Maysville, I returned to the cotton fields. I had gotten what I could at the Mission school and did all I could in the community to keep alive the interest in education, keeping up intercession for opportunity to train myself that I might be of service to others.

On one October day, our same teacher who had been joined by Mr. Simmons, a Negro man who had done so much for the Negro people, came to the farm field and said to mother and father that they had been sending out literature about the work done at Maysville mission. And a piece of the literature had gotten into the hands of a white woman in Denver, Colorado, Miss Mary Chrisman--

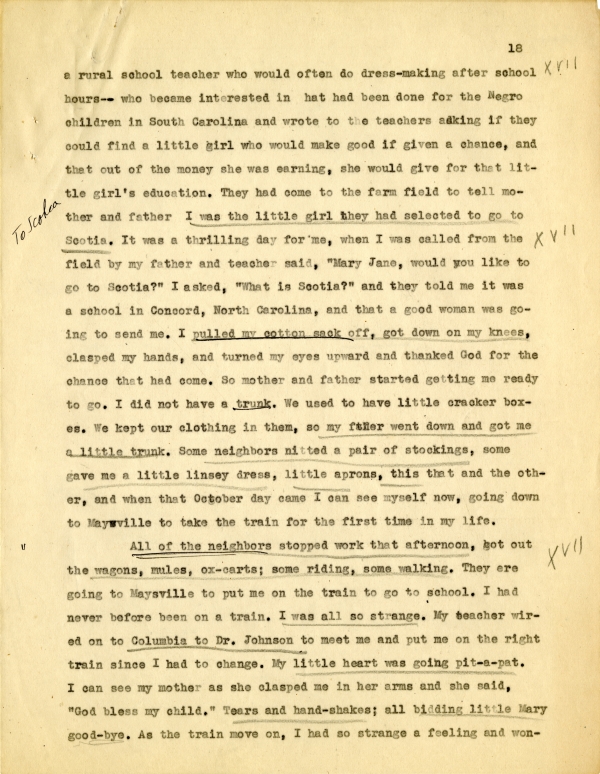

a rural school teacher who would often do dress-making after school hours – who became interested in what had been done for the Negro children in South Carolina. And (she) wrote to the teachers asking if they could find a little girl who would make good if given a chance, and that out of the money she was earning, she would give for that little girl's education.

They had come to the farm field to tell mother and father I was the little girl they had selected to go to Scotia. It was a thrilling day for me, when I was called from the field by my father and teacher said, "Mary Jane, would you like to go to Scotia?"

I asked, "What is Scotia?" and they told me that it was a school in Concord, North Carolina, and that a good woman was going to send me.

I pulled my cotton sack off, got down on my knees, clasped my hands, and turned my eyes upward and thanked God for the chance that had come.

So mother and father started getting me ready to go. I did not have a trunk. We used to have little cracker boxes. We kept our clothing in them, so my father went down and got me a little trunk.

Some neighbors knitted me a little linsey dress, little aprons, this and that and the other, and when that October day came I can see myself now, going down to Maysville to take the train for the first time in my life. All of the neighbors stopped work that afternoon, got out the wagons, mules, ox-carts; some riding, some walking. They were going to Maysville to put me on the train to go to school.

I had never before been on a train. It was all so strange. My teacher wired on to Columbia to Dr. Johnson to meet me and put me on the right train since I had to change. My little heart was going pit-a-pat. I can see my mother as she clasped me in her arms and she said, "God bless my child." Tears and hand-shakes; all bidding little Mary good-bye.

As the train moved on, I had so strange a feeling and won-

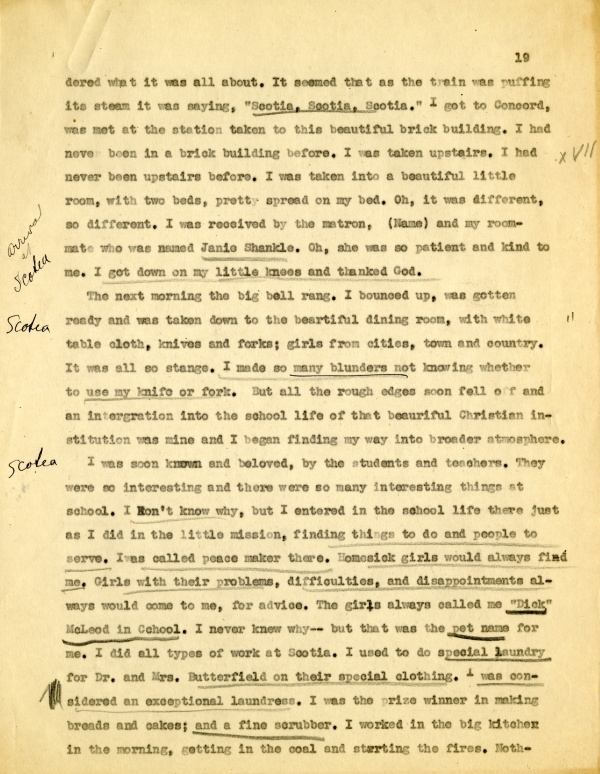

dered what it was all about. It seemed that as the train was puffing its steam it was saying, "Scotia, Scotia, Scotia."

I got to Concord, was met at the station taken to this beautiful brick building. I had never been in a brick building before.

I was taken into a beautiful little room, with two beds, pretty spread on my bead. Oh, it was different, so different. I was received by the matron, (Name) and my roommate who was named Janie Shankle. Oh, she was so patient and kind to me. I got down on my little knees and thanked God.

The next morning the big bell rang. I bounced up, was gotten ready and was taken down to the beautiful dining room, with white table cloth, knives and forks. I made so many blunders not knowing whether to use my knife or fork. But all the rough edges soon fell off and an integration into the school life of that beautiful Christian institution was mine and I began finding my way into broader atmosphere.

I was soon known and beloved, by the students and teachers. They were so interesting and there were so many interesting things at school. I don't know why, but I entered in the school life there just as I did in the little mission, finding things to do and people to serve. I was called peace maker there.

Homesick girls would always find me. Girls with their problems, difficulties, and disappointments always would come to me, for advice. The girls always called me "Dick" McLeod in school. I never knew why—but that was the pet name for me.

I did all types of work at Scotia. I used to do special laundry for Dr. and Mrs. Butterfield on their special clothing. I was considered an exceptional laundress.

I was the prize winner in making breads and cakes; and a fine scrubber. I worked in the big kitchen in the morning, getting in the coal and starting the fires. Noth-

ing was too menial or too hard for me to find joy in doing, for the appreciation of having a chance.

Oh, I was a member of the chorus class, the quartet, on the debating team. There was a great opportunity for me to prepare myself for the great task that was awaiting me.

It was the first time I had had a chance to study and know white people. They had a mixed faculty at Scotia. I can never doubt the sincerity and interest of some white people when I think of my experience with my beloved, consecrated teachers who took so much time and patience with me at a time when patience and tolerance were needed.

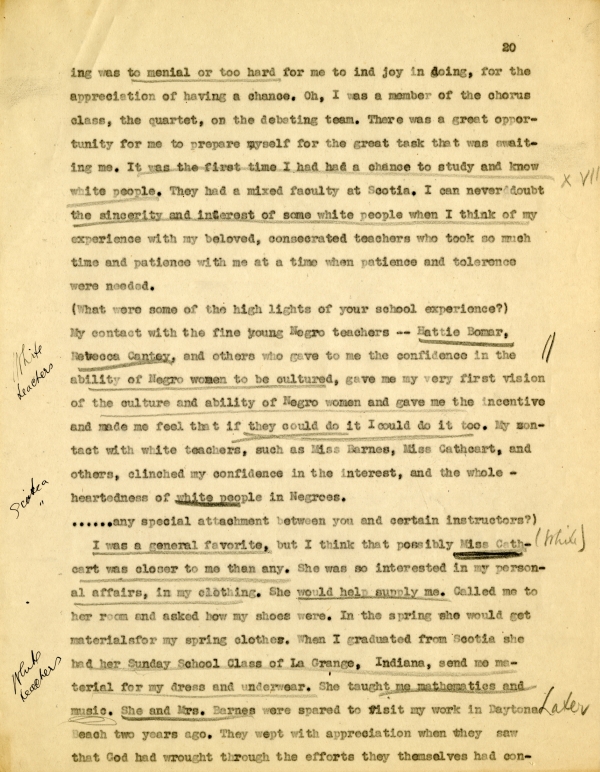

(What were some of the high lights of your school experience?)

My contact with the fine young Negro teachers – Hattie Bomar, Rebecca Cantey, and others who gave to me the confidence in the ability of the Negro women to be cultured, gave me my very first vision of the culture and ability of Negro women and gave me the incentive and made me feel that if they could do it I could do it too.

My contact with white teachers, such as Miss Barnes, Miss Cathcart, and others, clinched my confidence in the interest, the whole-heartedness of white people in Negroes.

(……any special attachment between you and certain instructors?)

I was a general favorite, but I think that possibly Miss Cathcart was closer to me than any. She was so interested in my personal affairs, in my clothing. She would help supply me. Called me to her room and asked how my shoes were. In the spring she would get materials for my spring clothes. When I graduated from Scotia she had her Sunday School Class of La Grange, Indiana, send me material for my dress and underwear. She taught me mathematics and music.

She and Mrs. Barnes were spared to visit my work in Daytona Beach two years ago. They wept with appreciation when they saw that God had wrought through the efforts they themselves had con-

tributed to me years ago. They now live in Concord, North Carolina.

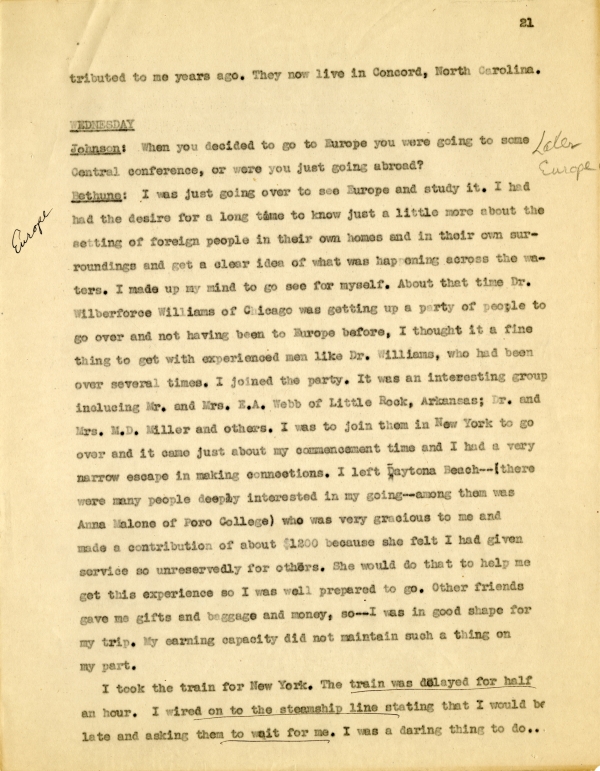

WEDNESDAY

Johnson: When you decided to go to Europe you were going to some Central conference, or were you just going abroad?

Bethune: I was just going over to see Europe and study it. I had had the desire for a long time to know just a little more about the setting of foreign people in their own homes and in their own surroundings and get a clear idea of what was happening across the waters. I made up my mind to go see for myself.

About that time Dr. Wilberforce Williams of Chicago was getting up a party of people to go over and not having been to Europe before, I thought it a fine thing to get with experienced men like Dr. Williams, who had been over several times. I joined the party. It was an interesting group including Mr. And Mrs. E.A. Webb of Little Rock, Arkansas; Dr. and Mrs. M.D. Miller and others.

I was to join them in New York to go over and it came just about my commencement time and I had a very narrow escape in making connections.

I left Daytona Beach -–(there were many people deeply interested in my going—among them was Anna Malone of Poro College) who was very gracious to me and made a contribution of about $1200 because she felt I had given service so unreservedly for others.. She would do that to help me get this experience so I was well prepared to go. Other friends gave me gifts and baggage and money, so—I was in good shape for my trip. My earning capacity did not maintain such a thing on my part.

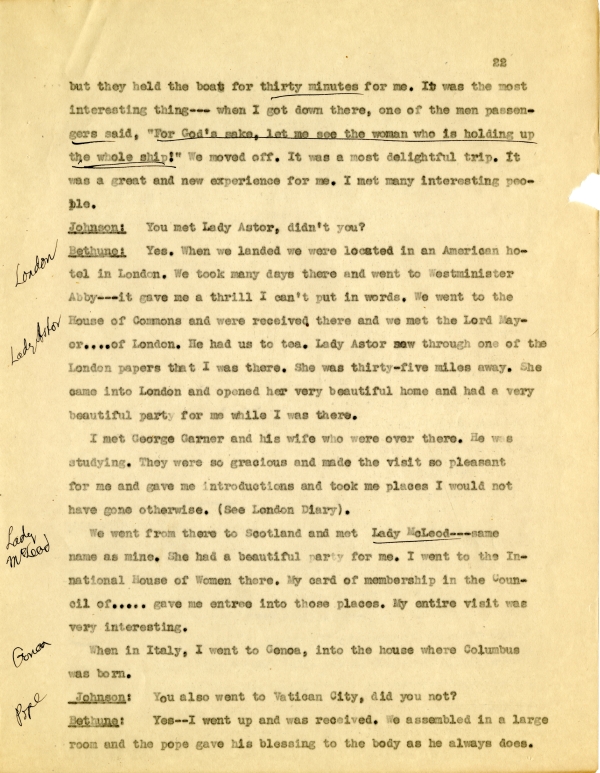

I took the train for New York. The train was delayed for half an hour. I wired on to the steamship line stating that I would be late and asking them to wait for me. It was a daring thing to do…

but they held the boat for thirty minutes for me. It was the most interesting thing—when I got down there, one of the men passengers said, "For God's sake, let me see the woman who is holding up the whole ship!" We moved off. It was a most delightful trip. It was a great and new experience for me. I met many interesting people.

Johnson: You met Lady Astor, didn't you?

Bethune: Yes. When we landed we were located in an American hotel in London. We took many days there and went to Westminster Abby--- it gave me a thrill I can't put into words. We went to the House of Commons and were received there and we met the Lord Mayor….of London. He had us to tea. Lady Astor saw through one of the London papers that I was there. She was thirty-five miles away. She came into London and opened her very beautiful home and had a very beautiful party for me while I was there.

I met George Garner and his wife who were over there. He was studying. They were so gracious and made the visit so pleasant for me and gave me introductions and took me places I would not have gone otherwise. (See London Diary)

We went from there to Scotland and met Lady McLeod---same name as mine. She had a beautiful party for me. I went to the International House of Women there. My card of membership in the Council of….. gave me entrée into those places. My entire visit was very interesting. When in Italy, I went to Genoa, into the house where Columbus was born.

Johnson: You also went to Vatican City, did you not?

Bethune: Yes—I went up and was received. We assembled in a large room and the pope gave his blessing to the body as he always does.

Everybody kissed his ring. When he came to me he stopped and held his hands over my head and said sentences in Latin. I do not know what he said—it was done too rapidly for translation.

I looked up into his face and said—"Pope Pius, I thank you." Webb and those men wept. And strangely, the attendant who was with the Pope put his arms about my shoulders and said, "Oh blessed art thou among women."

(I wonder why he said that? Do you know?) It was all so strange. We never knew---it must have been something very special.

Johnson:……..(lost in changing seat)

Bethune: He might have been calling(?) all the darker people of the world and he probably was paying a tribute to the rest of them. But there were Miller and other dark people there. But it did something to me—I don't know, but it did something to me.

And I think when I was in Rome we visited St. Peter's; down to the Alpian Way, and out on the Seven Hills there where Caesar and Brutus had their quarrel; the many interesting cathedrals—especially St. where hangs the painting of the Last Supper.

Johnson: I was especially interested in Lady Astor. How did she happen to know you? Had you met her before?

Bethune: No. She knew who I was. She had gone to an entertainment for Lindberg and saw in the paper that I was an educator and she wanted to come over and do something for me. She was beautiful to me. She said—"I am particularly proud because you are real, a real Negro, a real American—The things you are doing are so real and I want you to know I appreciate them. She is wonderful herself. The group with me…she was very generous in her whole setting for us.

I had a great experience in going around the Mediterranean. I was impressed with the cliff dwellers and the poverty of the people over there and the ignorance of the people

in Lower Italy.

Johnson: Were you impressed at any point with the great poverty of Europe over that of the Americas?

Bethune: I felt that the poorest peasants, the poorest share-croppers in Mississippi and Georgia were much better off than many of the poor white or rather waifs I saw. One gets many very different ideas—we are not the only sufferers and burden bearers in the world. I stiffened my back and got new courage to come back to America with greater appreciation for the blessings we did have.

Johnson: Mr. Washington had the same sort of shock when he was there and came back and wrote his book, "The Man Fartherest Down."

Bethune: It was the greatest thrill to go into the Blue Grotto. I thought Switzerland was beautiful but after all, I did not seem to see more real beauty in Europe than I see in sections of my own country. And I think of Lower Florida, Oregon and Washington State, sections of the West and California—Santiago. I did not see any beauty in Europe that I thought out-classed our own country. I was happy when I went to Europe that I had seen America first.

We were wonderfully received over there. The foreigners liked me very much. My dark skin did not hamper them at all. They were very fond of me. I liked them. I like folks. I had a birthday in Venice and all the Italians were very gracious—they made a cake for me. I had received a cablegram from America. They thought I was wonderful. All were fond of me. I was never lonesome. Someone was always with me. They came to keep me company. I had no lonely hours.

Johnson: I want to give you the privilege of four things from which to select the situation you feel like talking against.

(1) One of them is some of the things in the development of women's clubs in

America. No one has written their story yet. How they came into being and then how you became crystallized in these organizations and became head of these clubs and their leader, and established the Council of Women.

(2) To see were you conscious of any of the educational principals current about the time of the development of Bethune-Cookman.

(3) Your association with Lucy Laney and also with Booker T. Washington.

(4) Some of the New Deal personal stuff. Of course I know how Roosevelt turned with great feeling of ease and how you knew him well enough to shake your finger in his face and give him some friendly advice; and about your acquaintance with Mrs. James Roosevelt, and your contact with Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt. Your associations with that group has certain ramifications.

(5) A picture of Mr. Bethune.

Bethune: I think the educational situation of Florida and possibly of the lower East coast is very vague. I went there because I was looking for a hard place to work.

Johnson: How did you know Florida was hard?

Bethune: I knew of Florida….was building …down there and Negroes were flocking there and I went by to see what was being done.

Johnson: Did you know anyone there?

Bethune: No, when I went to Florida first….my first married year was in Savannah, Georgia. That was when I was quiet from active work. That year I took off.

My boy was born that year and I was engaged in civic things, church clubs, community work with women and children. On Robert's Street where I lived I had a group working with and for them, and while I was there my friend Irene Smallwood, who later became Mrs. J.W.E. Bowen, was with me when I taught at Lucy Laney's school. While visiting me in Savannah, a man named Reverend James C. U_gims(?) came to Savannah to visit Irene Smallwood.

I met him—he was the pastor of the Presbyterian church in Palatka, Florida.

I told him of going into a new district and how I wanted to build an institution of my own and wanted to go into some congested district where little was being done for my people and he suggested that I start a parochial school in connection with his church.

I got to Palatka and started out this community school and worked in the jails two and three times a week, and out to the sawmills there and in general among the young people in clubs there, and built up there a very interesting setting. I stayed there for five years.

Then I made up my mind to go down on the East coast and study the situation there and see what was being done—and found very little being done in that section. The new minister, Reverend S.P. Pratt, who told me he thought I would be interested to see what was happening in that section.

I had no money I was doing a little insurance work in connection with my other work—I sold insurance for the Afro-American and saved up a little money and went to the coast to study what was being done there.

As I studied the situation I saw the importance of someone going down there doing something—So I selected Daytona Beach, a town where very conservative people lived and where James N. Gamble (Of the Proctor & Gamble Company of Cincinnati); Thomas White, (of the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland); and other fine people. A fine club of white women in that section formed a philanthropic group of…Palmetto Club..through whom I thought approaches could be made.

The colored people had little to offer. A splendid man of the Baptist church, Rev. A.L. James; another fine man of the little Methodist Episcopal church…had conferences with these people and a little woman named Mrs. Warn, had some daughters who felt the im-

portance of some one doing something in that section and gave their cooperation with my idea of starting a school. I made up my mind that I would do it and started out.

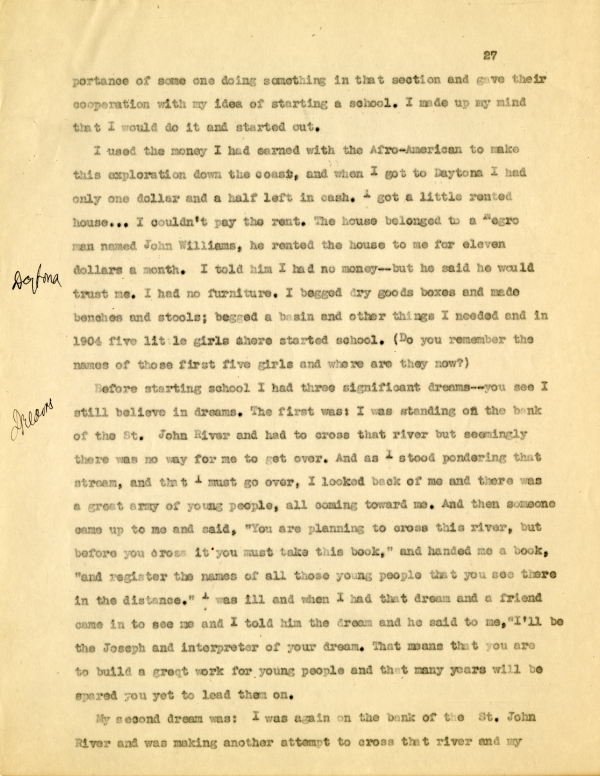

I used the money I had earned with the Afro-American to make this exploration down the coast, and when I got to Daytona I had only one dollar and a half left in cash.

I got a little rented house…I couldn't pay the rent. The house belonged to a Negro man named John Williams, he rented the house to me for eleven dollars a month. I told him I had no money—but he said he would trust me.

I had no furniture. I begged dry goods boxes and made benches and stools; begged a basin and other things I needed and in 1904 five little girls here started school.

(Do you remember the names of those first five girls and where are they now?)

Before starting school I had three significant dreams—you see I still believe in dreams.

The first was: I was standing on the bank of the St. John River and had to cross that river but seemingly there was no way for me to get over. And as I stood pondering that stream, and that I must go over, I looked back of me and there was a great army of young people, all coming towards me.

And then someone came up to me and said, "You are planning to cross this river, but before you cross it you must take this book," and handed me a book, "and register the names of all those young people that you see there in the distance."

I was ill and when I had that dream and a friend came in to see me and I told him about the dream he said to me, "I'll be the Joseph and interpreter of your dream. That means that you are to build a great work for young people and that many years will be spared you yet to lead them on."

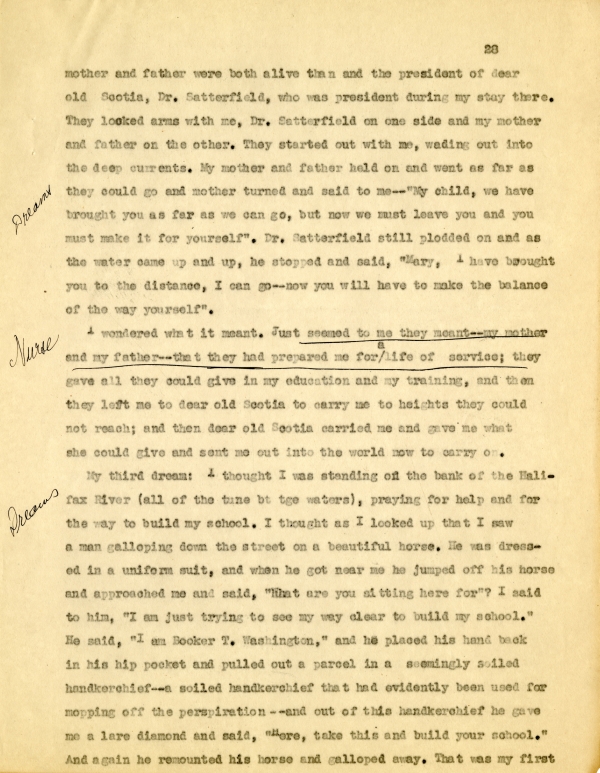

My second dream was: I was again on the bank of the St. John River and was making another attempt to cross that river and my

mother and father were both alive then and the president of dear old Scotia, Dr. Satterfield, who was president during my stay there. They locked arms with me, Dr. Satterfield on one side and my mother and father on the other. They started out with me, wading out into the deep currents. My mother and father held on and went as far as they could go and mother turned and said to me--"My child, we have brought you as far as we can go, but now we must leave you and you must make it for yourself." Dr. Satterfield still plodded on and as the water came up and up, he stopped and said, "Mary, I have brought you to the distance, I can go now--now you will have to make the balance of the way yourself."

I wondered what it meant. Just seemed to me they meant--my mother and by father--that they had prepared me for a life of service; they gave all they could give in my education and training, and then they left me to dear old Scotia to carry me to heights they could not reach; and then dear old Scotia carried me and gave what she could give and sent me out into the world now to carry on.

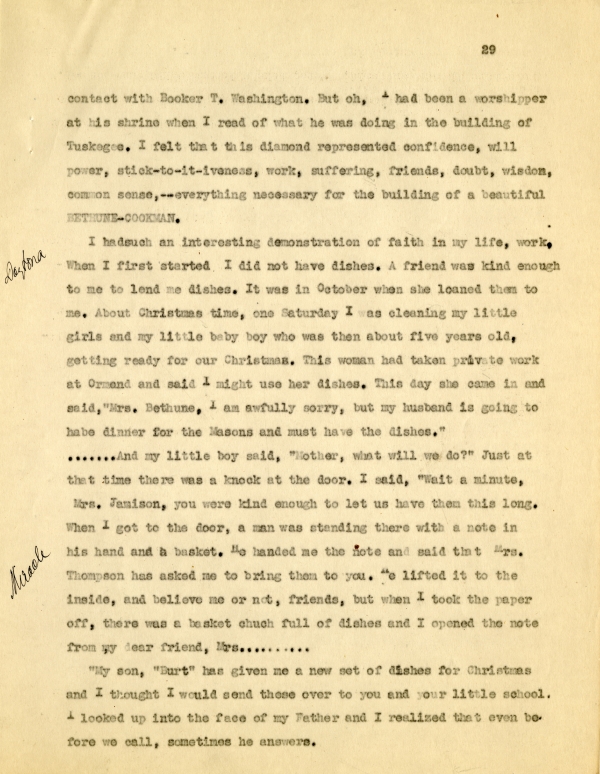

My third dream: I thought I was standing on the banks of the Halifax River (all of the ???waters), praying for help and for the way to build my school. I thought as I looked up that I saw a man galloping down the street on a beautiful horse. He was dressed in a uniform suit, and when he got near me he jumped off his horse and approached me and said, "What are you sitting here for?" I said to him, "I am just trying to see my way clear to build my school." He said, "I am Booker T. Washington," and he placed his hand back in his hip pocket and pulled out a parcel in a seemingly soiled handkerchief that had evidently been used for mopping off the perspiration –and out of this handkerchief he gave me a large diamond and said, "Here, take this and build your school." And again he remounted his horse and galloped away. That was my first

contact with Booker T. Washington. But oh, I had been a worshipper at his shrine when I read of what he was doing in the building of Tuskegee. I felt that this diamond represented confidence, will power, stick-to-it-iveness, work suffering, friends, doubt, wisdom, common sense,--everything necessary for the building of a beautiful BETHUNE-COOKMAN.

I had such an interesting demonstration of faith in my life, work. When I first started I did not have dishes. A friend was kind enough to me to lend me dishes. It was in October when she loaned them to me.

About Christmas time, one Saturday I was cleaning my little girls and my little baby boy who was then about five years old, getting ready for our Christmas. This woman had taken private work at Ormand and said I might use her dishes. This day she came in and said, "Mrs. Bethune, I am awfully sorry, but my husband is going to have dinner for the Masons and must have the dishes."

…….And my little boy said, "Mother, what will we do?" Just at that time there was a knock at the door.

I said, "Wait a minute, Mrs. Jamison, you were kind enough to let us have them this long."

When I got to the door, a man was standing there with a note in his hand and a basket. He handed me the note and said that Mrs. Thompson has asked me to bring them to you. He lifted it to the inside, and believe me or not, friends, but when I took the paper off, there was a basket chuch(sic) full of dishes and I opened the note from my dear friend Mrs……….

"My son, 'Burt' has given me a new set of dishes for Christmas and I thought I would send these over to you and your little school.

I looked up into the face of my Father and I realized that even before we call, sometimes he answers.

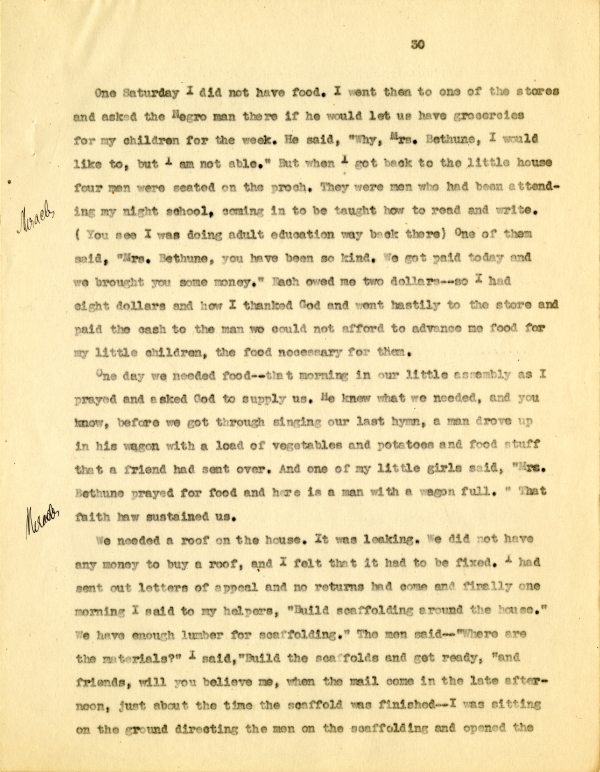

One Saturday I did not have food. I went to one of the stores and asked the Negro man there if he would let us have groceries for my children for the week.

He said, "Why Mrs. Bethune, I would like to, but I am not able."

But when I got back to the little house four men were seated on the porch. They were men who had been attending my night school, coming in to be taught how to read and write. (You see I was doing adult education way back there)

One of them said, "Mrs. Bethune, you have been so kind. We got paid today and we brought you some money."

Each owed me two dollars—so I had eight dollars and how I thanked God and sent hastily to the store and paid the cash to the man who could not afford to advance me food for my little children, the food necessary for them.

One day we needed food—that morning in our little assembly as I prayed and asked God to supply us. He knew what we needed, and you know, before we got through singing our last hymn, a man drove up in his wagon with a load of vegetables and potatoes and food stuff that a friend had sent over.

And one of the little girls said, "Mrs. Bethune prayed for food and here is a man with a wagon full." That faith has sustained us.

We needed a roof on the house. It was leaking. We did not have any money to buy a roof, and I felt that it had to be fixed.

I had sent out letters of appeal and no returns had come and finally one morning I said to my helpers, "Build scaffolding around the house. We have enough lumber for scaffolding."

The men said—"Where are the materials?"

I said, "Build the scaffolds and get ready," and friends, will you believe me, when the mail come in the late afternoon, just about the time the scaffold was finished—I was sitting on the ground directing the men on the scaffolding and opened the

mail bag right where I was sitting and will you believe me—I opened the letter from a darling friend who had sent me one thousand dollars to be used as I needed it.

And I called my men then from the scaffold and we bowed in prayer there together, thanking God for the supply. I could not help but remember the story of the building of the alter—how Abraham was commanded to build the alter and give an offering and when he looked around for a ram it was there. That is the kind of faith that has built Bethune-Cookman.

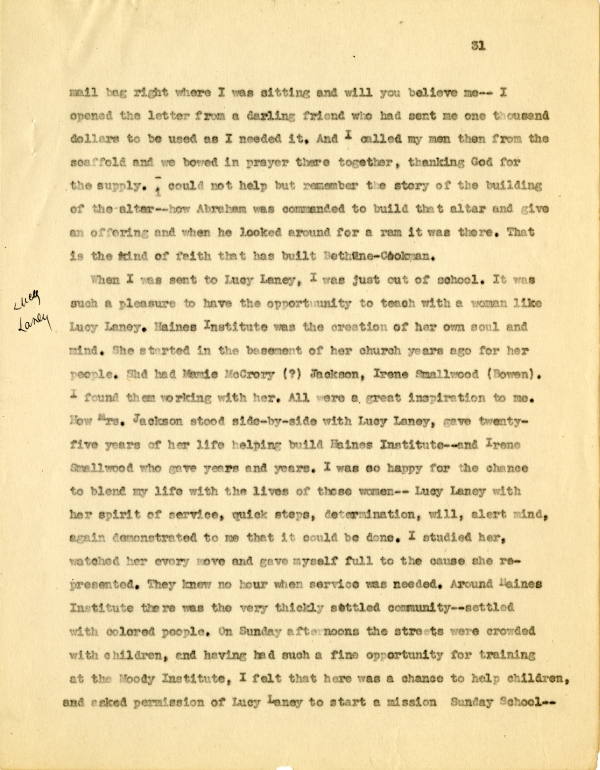

When I was sent to Lucy Laney, I was just out of school. It was a pleasure to have the opportunity to teach with a woman like Lucy Laney. Haines Institute was the creation of her own soul and mind. She started in the basement of her church years ago for her people. She had Mamie McCrory (?) Jackson, Irene Smallwood (Bowen). I found them working with her. All were a great inspiration to me. How Mrs. Jackson stood side-by-side with Lucy Laney, gave twenty-five years of her life helping build Haines Institute—and Irene Smallwood who gave years and years. I was so happy for the chance to blend my life with the lives of those women—Lucy Laney with her spirit of service, quick steps, determination, will, alert mind, again demonstrated to me that it could be done. I studied her, watched her every move and gave myself full to the cause she represented. They knew no hour when service was needed.

Around Haines Institute there was the very thickly settled community—settled with colored people. On Sunday afternoons the streets were crowded with children, and having had such a fine opportunity for training at the Moody Institute, I felt that here was a chance to help children, and asked permission of Lucy Laney to start a mission Sunday School—

she granted it.

she granted it.

I took the girls of the science class and my own class and went out and combed the alleys and streets and brought in hundreds of children until we had a Sunday School of almost a thousand young people and people in the community came in. Among whom was Judson Lyons and others.

This mission school lasted for years, and became one of the great assets of Haines Institute, Lucy Laney, the great inspirer, the great educator, the great leader among our group, fired me with greater ambition for service.

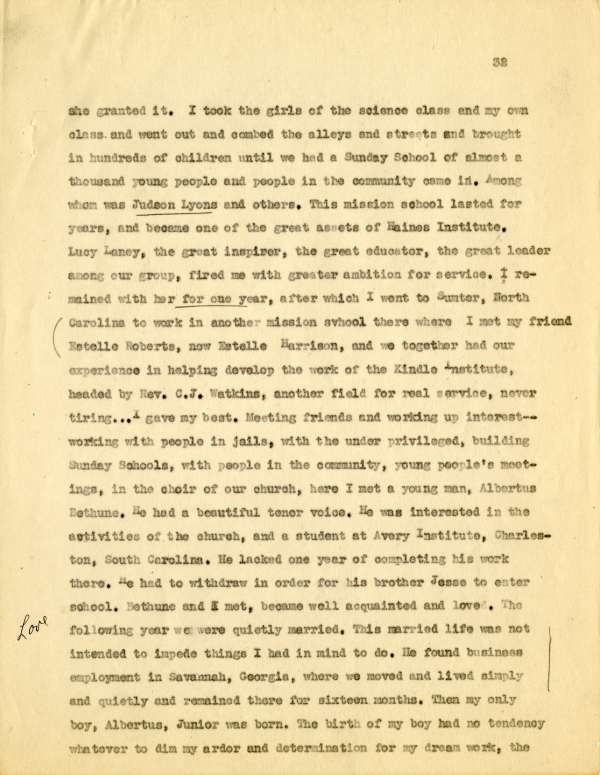

I remained with her for one year, after which I went to Sumter, North Carolina to work in another mission svhool(sic) there where I met my friend Estelle Roberts, now Estelle Harrison, and we together had our experience in helping develop the work of the Kindle Institute, headed by Rev. C.J. Watkins, another field for real service, never tiring…I gave my best. Meeting friends and working up interest—working with people in jails, with the under privileged, building Sunday Schools, with people in the community, young people's meetings, in the choir of our church.

Here I met a young man, Albertus Bethune. He had a beautiful tenor voice. He was interested in the activities of the church, and a student at Avery Institute, Charleston, South Carolina. He lacked one year of completing his work there. He had to withdraw in order for his brother Jesse to enter school.

Bethune and I met, became well acquainted and loved. The following year we were quickly married. This married life was not intended to impede things I had in mind to do. He found business employment in Savannah, Georgia, where we moved and lived simply and quietly and remained there for sixteen months.

Then my only boy, Albertus, Junior was born. The birth of my boy had no tendency whatever to dim my ardor and determination for my dream work, the

building of an institution.

Mr. Bethune was not interested in educational work, but put no barriers in my way to carry on my work. It was mine to struggle on alone. He died in the early years of my beginning, without realizing the possibilities of my ambitions.

(Something personal about Mr. Bethune? His background, etc.)

I met him after he was grown. He was reared in South Carolina and educated there. He was a very fine young man, with fine parentage and family—average in educational background and interested in business.

General Note

Chicago Manual of Style

Johnson, Charles Spurgeon, 1893-1956. Mary McLeod Bethune Interview Transcript, ca. 1939. 1939 (circa). State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. <https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/333794>, accessed 4 March 2026.

MLA

Johnson, Charles Spurgeon, 1893-1956. Mary McLeod Bethune Interview Transcript, ca. 1939. 1939 (circa). State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. Accessed 4 Mar. 2026.<https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/333794>

AP Style Photo Citation

(State Archives of Florida/Johnson)

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program