Description of previous item

Description of next item

History Beneath the Waves

Published August 8, 2018 by Florida Memory

There’s an important piece of Florida and United States history located about a mile and half southwest of Pensacola Pass in the Gulf of Mexico. There’s not much to see on the surface, just a couple of rusty cylinders that look as though they might have once been the foundation for a platform or a beacon of some sort. They’re just the tip, however, of something much more significant lying beneath the waves–the final resting place of one of the United States’ oldest battleships, the USS Massachusetts.

A portion of the submerged USS Massachusetts, located southwest of the entrance to Pensacola Bay (1993). Box 5, Folder 18, Archaeological Sites and Activities Slide and Video Recordings – Bureau of Archaeological Research (Series S2318), State Archives of Florida.

The Massachusetts (BB-2) was launched in 1893 as part of the United States’ new “Steel Navy.” Naval vessels were becoming faster and more deadly as the technology behind guns and engines improved. Congress realized a strong navy was critical to national security, so in 1890 it authorized the construction of three steel-hulled, armored battleships powered entirely by steam. These ships, termed the Indiana class, included the Indiana, the Massachusetts and the Oregon. The Massachusetts was built by William Cramp and Sons of Philadelphia; the keel was laid on June 25, 1891, and the completed ship was launched on June 10, 1893. Officially commissioned by the Navy in 1896, the battleship was 350 feet long, 69 feet wide at the center and had a draft of 24 feet. Its top speed was 15 knots, and it featured two 13-inch guns and eight 8-inch guns along with smaller armaments.

After being fitted out at Philadelphia, the Massachusetts was assigned to the Navy’s North Atlantic fleet and spent several years traveling up and down the Eastern Seaboard on maneuvers. The ship’s first military action came during the Spanish-American War in 1898. On May 31 of that year, the Massachusetts joined the Iowa and New Orleans in firing on the Spanish warship Cristóbal Colón off the coast of Santiago, Cuba. The Massachusetts missed out on the rest of the ensuing battle, having been forced to steam over to Guantanamo Bay to refuel. On July 4, the ship helped sink the Spanish cruiser Reina Mercedes and later steamed over to Puerto Rico to help transport troops during the U.S. occupation of the island.

The so-called “black gang” of the USS Massachusetts, nicknamed for their blackened faces and clothing resulting from long days shoveling coal in the ship’s boiler room (circa 1918).

The Massachusetts had a relatively short service period, coming along in a time when naval technology was improving rapidly and older ships quickly became obsolete. It did have its high points, however. It was one of the first ships to have a permanent wireless telegraph system aboard, the installation being supervised directly by the inventor of the wireless telegraph, Guglielmo Marconi. During a European tour in 1911 it marked the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary of England with a 21-gun salute on behalf of the United States. The following year, the Massachusetts had the honor of offering a similar salute for President William Howard Taft during a review of the fleet at New York City.

The Massachusetts was decommissioned in 1914 (actually for the second time), but the outbreak of World War I led naval authorities to put it back into service as a gunnery practice ship for reserve crews training off the Atlantic coast. The ship returned to Philadelphia after the war, where it was decommissioned permanently and struck from the official Navy List. With no more missions to complete, the Navy offered the Massachusetts to the War Department, which decided to use it for target practice for coastal defenses near Pensacola. In January 1921, the Navy towed the ship around the tip of Florida and anchored it just outside the entrance to Pensacola Bay. The first attempt to scuttle the ship backfired when naval authorities realized the spot they had chosen was too shallow, and the ship had to be painstakingly refloated and moved to deeper water.

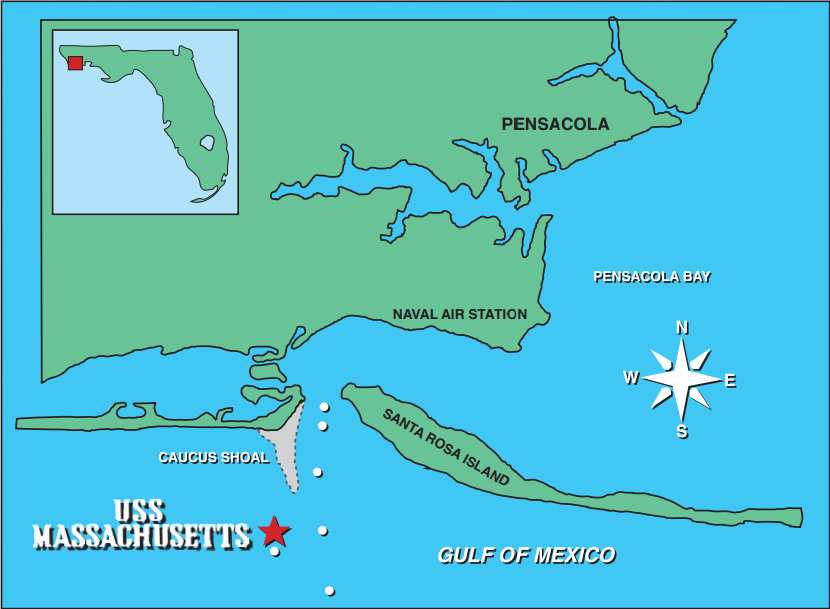

Map showing the location of the USS Massachusetts in relation to Pensacola and Santa Rosa Island. Included in an informational brochure on the USS Massachusetts published by the Florida Department of State, Division of Historical Resources in 2013.

Meanwhile, the Army set up coastal artillery pieces at Fort Pickens on Santa Rosa Island and Fort Barrancas on the mainland and aimed them at the sunken ship. For 12 days they fired on the Massachusetts, stopping periodically to study the damage done by different kinds of ammunition shot from various angles. By the end of the month, the tests were complete, and the ship was abandoned with parts still protruding from below the waves of the Gulf.

A diver explores part of the wreckage of the USS Massachusetts (1993). Box 5, Folder 18, Archaeological Sites and Activities Slide and Video Recordings - Bureau of Archaeological Research (Series S2318), State Archives of Florida.

Despite having been underwater for nearly a century, the USS Massachusetts has been an uncommonly useful shipwreck. During World War II, student aviators from Naval Air Station Pensacola used the ship for target practice, and parts of its superstructure were harvested for urgently needed scrap metal. It was declared a Florida Underwater Archaeological Preserve in 1993 and has become a popular site for both diving and fishing. Amberjack, cobia, grouper and snapper are just a few of the game fish that make their home in the decaying hull of the Massachusetts.

Looking for more information and photos relating to Florida shipwrecks? Try searching the Florida Photographic Collection, and visit the Florida Museums in the Sea website, a fun, easy way to learn more about Florida’s twelve Underwater Archaeological Preserves.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "History Beneath the Waves." Floridiana, 2018. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/334334.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "History Beneath the Waves." Floridiana, 2018, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/334334. Accessed March 9, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2018, August 8). History Beneath the Waves. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/334334

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program