Description of previous item

Description of next item

Rejoining the Union

Published August 8, 2018 by Florida Memory

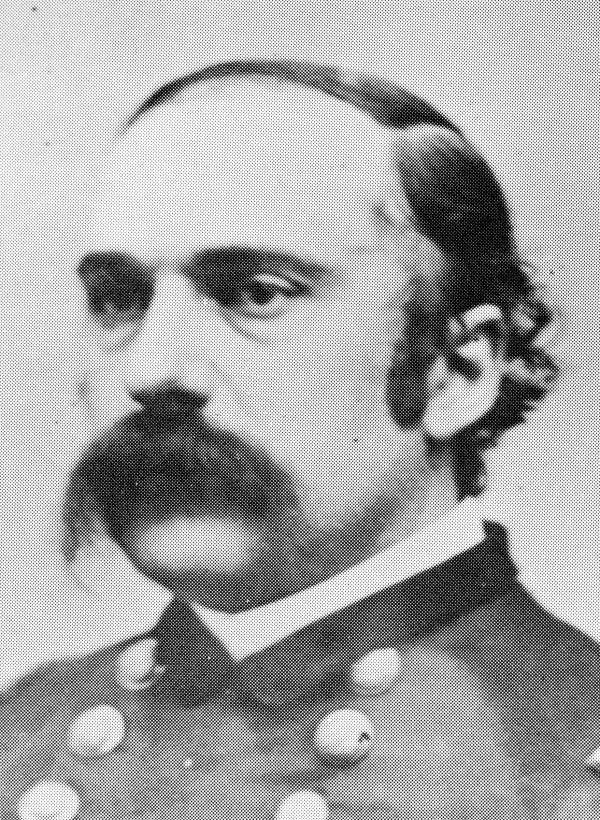

It was May 10, 1865. The Civil War was over; General Robert E. Lee had surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House in Virginia the previous month. Telegraph lines were down all over the South, and many Floridians didn’t trust what they were hearing about the defeat of the Confederate Army. The ones in Tallahassee had little choice but to believe, however, when Brigadier General Edward Moody McCook came to town that day to accept the surrender of the remaining Confederate troops in Florida.

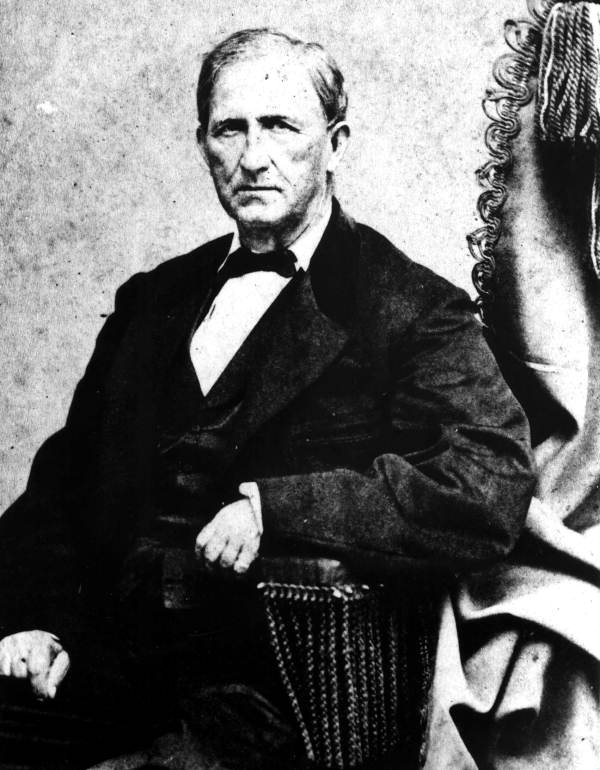

Governor John Milton, who had led Florida through much of the war, was dead. His successor, State Senate President Abraham K. Allison of Gadsden County, was now in charge, but what would happen to Florida now? Duly elected representatives of the people had signed an ordinance of secession in 1861 declaring the state a “Sovereign and Independent Nation.” Would Florida automatically become a part of the United States again? And if not, on what terms could it rejoin?

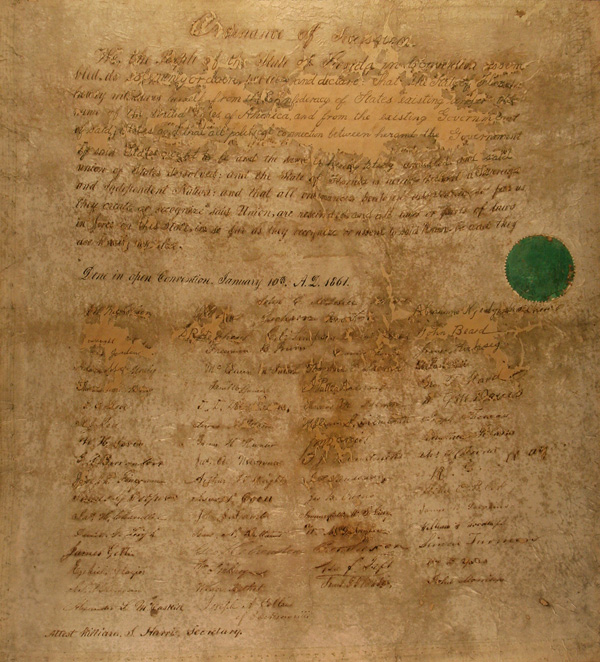

Ordinance of Secession, signed January 10, 1861, by 62 of the 69 delegates who attended a convention in Tallahassee to determine whether Florida would secede following the election of Abraham Lincoln (Series S972, State Archives of Florida). Click the image to enlarge it and see a full transcript.

Unfortunately, the United States government was a little unsure about this issue as well. President Abraham Lincoln had viewed Reconstruction after the war as something the executive branch would handle. The way he saw it, the Confederate states had never really left the Union in the first place; they were just temporarily in the hands of disloyal rebels. Once loyal governments were back in control, the states would effectively be back in the United States. Lincoln devised what he called the Ten Percent Plan to establish a process for making this happen. To rejoin the United States, a state would need 10 percent of its electorate (as of 1860) to take an oath of allegiance and for the state government to form a new constitution that:

- Abolished slavery.

- Repudiated any debts the state had incurred during the war.

- Repealed the state’s ordinance of secession.

Lincoln’s plan never got very far–John Wilkes Booth assassinated the president before any state had met the requirements for readmission. That left Lincoln’s vice-president, Andrew Johnson, in charge. Johnson, himself a Southerner, favored his predecessor’s approach, but he faced serious opposition in Congress to such a lenient set of readmission requirements.

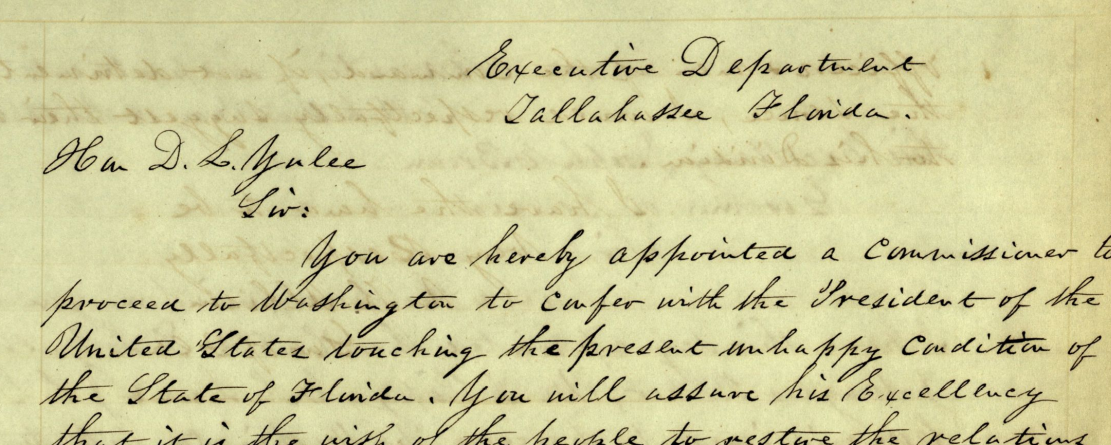

Meanwhile in Florida, Governor Abraham K. Allison wanted to take advantage of Johnson’s sentiments and normalize relations between his government and the U.S. as quickly as possible. Without consulting General McCook, he commissioned five representatives–David Levy Yulee, John Wayles Baker, Edward Curry Love, Mariano D. Papy, and James Lawrence George Baker–to confer with the president about readmission. Allison also summoned the state Legislature to convene on June 5, 1865, and set June 7 as the date for electing a new governor.

Letterbook Copy of David Levy Yulee’s commission from Governor Abraham K. Allison to Confer with President Andrew Johnson – May 12, 1865. Governors’ Letterbooks (Series S32), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to view the complete document and transcript.

Governor Allison’s actions shocked Florida’s Unionists, who had figured they would be closely involved in rebuilding the state’s relationship with Washington. General McCook was caught off guard as well, so he asked his superiors for instructions. As much as President Johnson had hoped to readmit the former Confederate states quickly, Allison’s actions went too far too fast. McCook received orders not to recognize any local or state government. The general placed the entire state under martial law on May 22, and Governor Allison was arrested and jailed, along with a number of other top state officials.

General Edward Moody McCook, who arrived in Tallahassee on May 10, 1865, to receive the surrender of Confederate troops in Florida.

President Johnson appointed William Marvin of Key West as provisional governor on July 23, 1865. Marvin was given authority to handle civil affairs, but the state remained under martial law. He called an election for October 10, 1865, to choose delegates for a constitutional convention at Tallahassee, which was to begin later that month. Although a considerable faction of the Republican Party in Congress had made it clear they wanted African-Americans to be able to vote in these elections, President Johnson didn’t make the idea more than a suggestion in his instructions to the states, and Florida did not permit its black citizens to vote. As a result, the convention was made up of most of the same people who had been in charge before the war, and their ideas about the place of African-Americans in society had not changed.

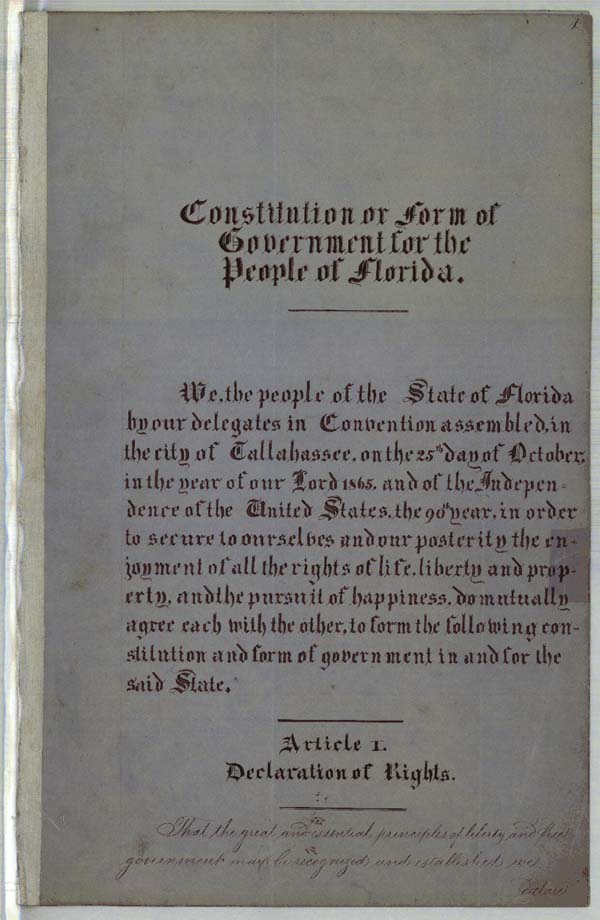

The framers of Florida’s new constitution accepted the 13th Amendment ending slavery, repudiated Florida’s war debt and agreed to annul the ordinance of secession. They did not, however, grant African-Americans the right to vote. Moreover, the new legislature established a series of laws–called Black Codes–relating specifically to the behavior of African-Americans. They were similar to the slave codes that had been in force through the end of the war. This pattern was repeated across all of the former Confederate states, which gave Northerners the impression that the South meant to retain as much of slavery as they could.

Florida’s 1865 Constitution (Series S58, State Archives of Florida). Click or tap the image to view the complete document with transcript.

Congress reacted to these developments in two ways. First, the sitting members refused to seat newly elected delegates from the former Confederate states. Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution grants each house of Congress the power to judge the qualifications of its own members, which made this action possible. Congress also passed a civil rights bill establishing African-Americans as citizens and placing certain rights under the protection of the federal government, essentially invalidating the Black Codes. President Johnson vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode his veto. When some lawmakers questioned the constitutionality of the new law, Congress reinforced it by drafting the 14th Amendment, which would make many of the same principles part of the Constitution itself.

Of the Southern states, only Tennessee ratified the 14th Amendment. This further demonstrated to Northerners that the former Confederate states would have to be compelled to accept the new political rights they envisioned for African-Americans. The 1866 election resulted in a Congress with all the necessary votes to override a presidential veto on this subject, so lawmakers took control of the process the following spring. On March 2, 1867, Congress passed the Reconstruction Act over President Johnson’s veto. The act reestablished martial law in every former Confederate state except for Tennessee. It also declared their governments “provisional” and set up a new process for readmitting them to the Union. To qualify, a state would have to:

- Register all of its eligible voters, meaning all males 21 years of age and older, without regard to race or color.

- Hold elections for delegates to a constitutional convention.

- Frame a new state constitution guaranteeing males 21 years and older the right to vote without regard to race or color.

- Ratify the 14th Amendment.

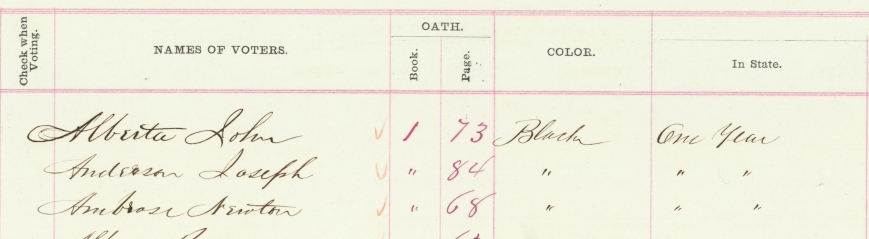

Florida began registering voters according to the new rules in August 1867. Ossian Bingley Hart of Jacksonville, who would later become governor, was appointed to supervise the registration process. Many former Confederates chose not to register, even if they were qualified, perhaps out of a feeling of futility or sympathy for friends who were disqualified from registering because of their involvement with the Confederate government. At any rate, Hart’s registration drive resulted in 11,148 white voters and 14,434 black voters, who went to the polls without incident in November 1867 to select delegates for a constitutional convention.

Excerpt from the 1867-68 voter registration rolls completed in compliance with the Reconstruction Act of 1867. Rolls for 19 Florida counties survive and are searchable on Florida Memory. Click or tap the image to view the collection (Series S98, State Archives of Florida).

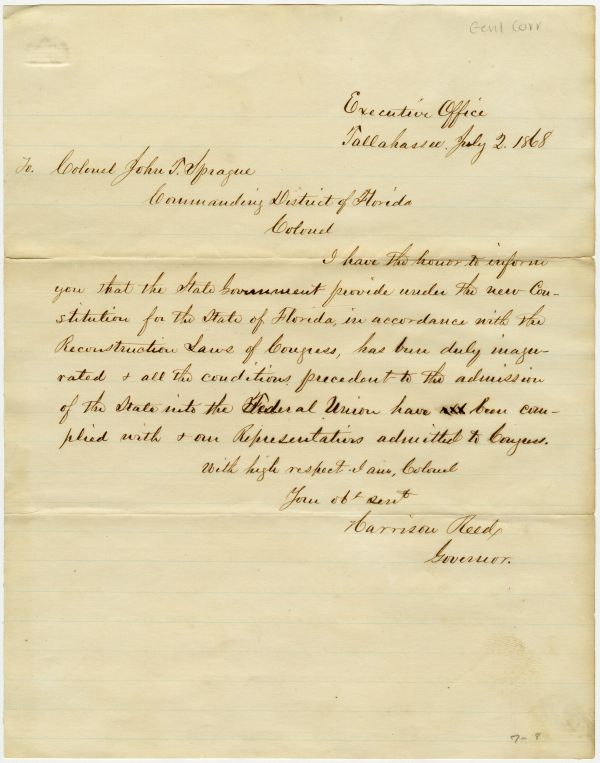

Republicans had the majority this time around, but they were divided into factions, which resulted in a colorful series of events at the convention in 1868. They did manage to produce a constitution, however, and an election was held to choose a new slate of state officers. Harrison Reed, a Wisconsin native who had come to Florida on a federal appointment during the war, was elected governor. He was inaugurated on June 8, 1868, and the Legislature ratified the 14th Amendment the following day. On July 2, Governor Reed wrote the following note to John T. Sprague, the colonel supervising Florida’s second Union occupation, announcing that Florida had met the requirements for readmission to the Union:

Letter from Governor Harrison Reed to Colonel John T. Sprague announcing that Florida had met the requirements for Florida to be readmitted to the Union. Box 4, Folder 6, Governors’ Correspondence (Series S577), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it and read the transcript.

Congress received a copy of the new state constitution and officially readmitted Florida to the Union on July 25, 1868. This was only the beginning of Reconstruction, of course. Considerable challenges lay ahead both inside and outside the halls of government. The Sunshine State was, however, officially part of the United States of America once again.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Rejoining the Union." Floridiana, 2018. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/341933.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Rejoining the Union." Floridiana, 2018, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/341933. Accessed January 31, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2018, August 8). Rejoining the Union. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/341933

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program