Description of previous item

Description of next item

The First Known Christmas in Florida

Published December 12, 2018 by Florida Memory

Florida has the unique distinction of being the probable site of the first Christmas celebration ever held in what is now the United States. Archaeological and documentary evidence suggests that Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto and his expedition of more than 600 soldiers, slaves, craftsmen and adventurers observed the holiday while encamped at the Apalachee town of Anhaica, located where Tallahassee now stands.

Illustration of Hernando de Soto from Justin Winsor, ed., Narrative and Critical History of America, vol. 2 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin and Co., 1886).

Hernando de Soto had already participated in Spanish conquests in Central and South America by 1537, when King Charles V granted him the right to explore and conquer “La Florida.” Previous expeditions by Pánfilo de Narváez and Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón had reached Florida but had failed to establish permanent colonies. De Soto set out from Havana, Cuba on May 18, 1539 with 600 soldiers, 223 horses, nine ships and a host of servants, slaves and other participants. The expedition reached Florida on May 25th. Scholars have debated over where exactly the conquistador and his party landed, but most interpretations suggest they arrived the vicinity of Tampa Bay. De Soto spent the summer and fall of 1539 making his way up the Florida peninsula, searching for precious metals or other resources valuable to Spain and his own coffers. He encountered many native tribes along the way, who–not surprisingly–opposed the expedition’s intrusion into their territory. The natives used cane arrows tipped with fish bones, crab claws and stone points to attack the Spaniards, while de Soto’s army used their own cruel methods to compel the natives’ submission.

Map showing the routes and settlement sites of Spanish explorers during the colonial era, including Hernando de Soto. From the Division of Historical Resources’ booklet titled Florida Spanish Colonial Heritage Trail (2009).

On October 3, 1539, the expedition crossed the Aucilla River–now the boundary between Jefferson and Madison counties in North Florida–and entered the province of Apalachee. Three days later, de Soto reached the principal Apalachee town of Anhaica, located in what is now Tallahassee. With winter fast approaching, de Soto ordered his followers to establish a camp, where they would remain until March 3, 1540. The location of de Soto’s camp was revealed in 1987 when State Archaeologist B. Calvin Jones uncovered artifacts from the expedition’s stay at a construction site just south of U.S. 27, just under a mile from the State Capitol. A small army of archaeologists and volunteers descended on the site, finding several copper coins, an iron crossbow point, nails, links of chain mail, broken Spanish olive jars and perhaps one of the most telling artifacts of all–the jawbone of a pig dating to around the time of de Soto’s expedition. Since de Soto had been the one to introduce the pig to North America, this was almost certainly a sign that he had been there.

Artifacts discovered at the site of Hernando de Soto’s 1539-40 winter encampment in what is now Tallahassee (1987).

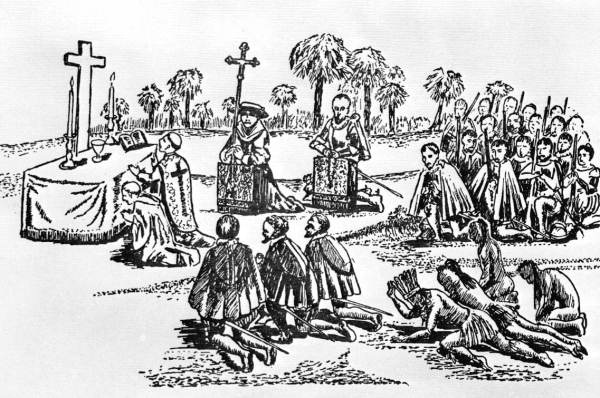

The dates of de Soto’s stay at Anhaica confirm he spent Christmas there, but how did the expedition celebrate? The documentary evidence is scant, but we can make a few educated guesses based on what we do know. There were, for example, 12 Catholic priests included in the expedition, so it’s likely they held a traditional Catholic mass to mark the occasion. Also, the Apalachee natives had fled Anhaica before the Spaniards arrived, but they left behind immense stores of maize and beans, which de Soto and his followers used for their own sustenance. Did they have a Christmas feast similar to those still held today? Did the menu include the pig whose jawbone was found by Calvin Jones more than 400 years later? It’s quite possible.

An artist’s depiction of the first Christmas celebrated in what is now the United States by Hernando de Soto’s expedition in 1539.

While this may have been the first Christmas celebrated in what is now the United States, it was certainly not a time of peace and joy for de Soto, his followers or the Apalachees they displaced. The natives who had evacuated Anhaica ahead of the expedition besieged the intruders, regularly attacking their garrison and hunting parties, and attempting to burn the town down by flinging torches and shooting flaming arrows into it. De Soto responded in kind, using ruthless tactics to bring the Apalachees to heel. The expedition lost 20 members while encamped at Anhaica. The number of Apalachees killed by Spanish attacks, disease or starvation is unknown.

Despite the less than festive circumstances surrounding Hernando de Soto’s time in Tallahassee, the winter encampment site was a critical find. Until recently, it was the only place where verifiable physical evidence of the expedition had been found. The property, which includes the former home of Florida’s Governor John W. Martin, has since been purchased by the state and is now headquarters for the Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "The First Known Christmas in Florida." Floridiana, 2018. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342048.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "The First Known Christmas in Florida." Floridiana, 2018, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342048. Accessed March 5, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2018, December 12). The First Known Christmas in Florida. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342048

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program