Description of previous item

Description of next item

Sawing Logs

Published January 1, 2019 by Florida Memory

Florida’s economy was still mostly agricultural in the late 1800s. The Civil War had ended slavery, but that system was replaced by sharecropping and tenant farming, in which many former slaves–and a number of white citizens as well–rented patches of land in exchange for a “share” of the crops they grew on them. For Florida’s many small freehold farmers who owned their own land, the norm was to produce what they needed to be comfortable, as well as enough of a cash crop like corn or cotton to cover their general store debts and their annual taxes to the county and state. In all of these systems, cash only came in a couple of times per year when crops were harvested. As a result, farmers relied heavily on credit from their landlords and local merchants, and after paying them off each year there was often little if any cash left. Many times, a farmer’s crop wouldn’t even cover his debts, and he might even go so far as to mortgage the next year’s crop to satisfy his creditors. Droughts, bad storms, insects and production shortfalls could easily wreak havoc on a farmer’s plans under these conditions.

Wagons unloading cotton at the Seaboard Air Line depot in Lloyd in Jefferson County, Florida (ca. 1890).

So what could you do if you were a farmer who wanted to make a little extra money to get ahead? The options were few outside the cities, but there was one natural resource that Florida had plenty of that farmers learned to take advantage of in the late 1800s–timber. Even 30 years into statehood, Florida’s government still held title to a tremendous amount of land, which was generally covered with thick stands of valuable timber. Cedar, cypress and yellow pine were the most sought-after varieties. In the late 1870s, the Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Fund, which managed these lands for the state, came up with a plan to license private individuals to cut timber on state lands for a small fee. The earliest records from this system are held by the State Archives in Tallahassee, and have recently been digitized and made available on FloridaMemory.com. Besides helping us better understand the so-called “stumpage system,” they may also be useful for researchers working on family trees with ancestors living in Florida in the late 1870s and early 1880s.

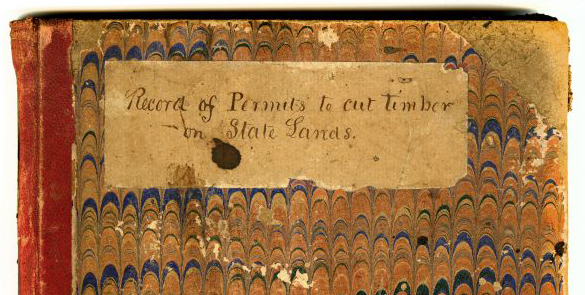

Cover of the volume in which the Trustees of the Internal Improvement Fund recorded the permits they issued for cutting timber on state lands (Series S 1814, State Archives of Florida). Click or tap the image to view the entire book.

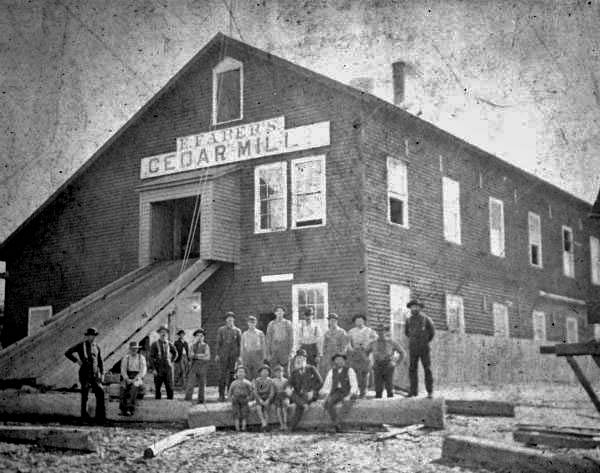

First, some background. The stumpage system came into being after several state officials and county sheriffs warned the board in 1879 that private citizens were trespassing on state lands to cut cedar timber, particularly in Levy, Lafayette and Taylor counties. The German pencil magnate Eberhard Faber had established a cedar slat factory on Atseena Otie (Cedar Key) around 1855, and by the 1870s the company was shipping upwards of a million cubic feet of trimmed cedar annually for the purpose of making pencils. Faber originally got the wood from his own extensive timber holdings in the vicinity of the factory on Atseena Otie, but over time the nearby wood supply was exhausted. With cedar in high demand, Floridians living close to the Gulf coast or along the Suwannee or Withlacoochee rivers saw an opportunity to make some extra cash. There were almost no railroads in the area at this time, and carting the logs over land to Cedar Key would have been impractical, but if a seller could float the cedar logs down a creek or river to the Gulf and then raft them to Cedar Key, he could sell them for a good price.

Workers gathered outside Eberhard Faber’s cedar mill on Atseena Otie (Cedar Key). Photo circa 1890s.

The problem was that these Floridians weren’t just cutting the cedar trees from their own land. As officials told the Internal Improvement Fund trustees, there were a number of cases where a citizen either started cutting on his own land and simply went outside his boundaries, or just willfully cut trees from state lands. It wasn’t hard to do in those days, of course. Very little land in North Florida was developed at this time, practically none of it was marked and the state did not regularly patrol its holdings because they were so extensive.

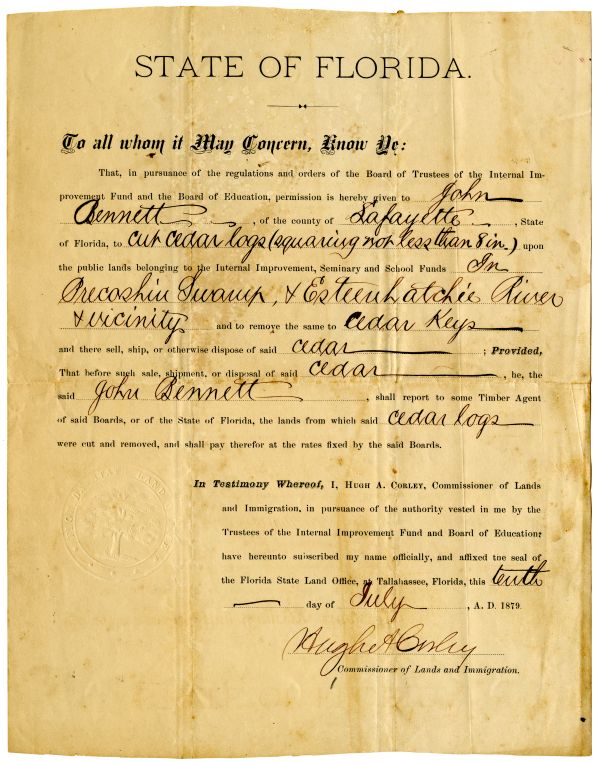

At its June 11, 1879 meeting, the Trustees of the Internal Improvement Fund decided to allow private citizens to cut timber on the state’s land, but only if they paid a “stumpage” fee. For cedar and palmetto, the rate would be 10 cents per cubic foot. For pine and cypress it was 50 cents per cubic foot. Moreover, no cedar could be cut unless the log would make an 8-inch square when dressed. To get permission to begin cutting, a citizen simply let the Commissioner of Lands and Immigration know where he wanted to cut timber, what kind of timber it was and where it would be taken, promising to pay a state timber agent the appropriate amount of stumpage. The Commissioner would then issue a permit like this one:

Permit for John Bennett of Lafayette County to cut cedar logs in the vicinity of the Esteenhatchie (Steinhatchee) River, 1879 (Series S 1814, State Archives of Florida).

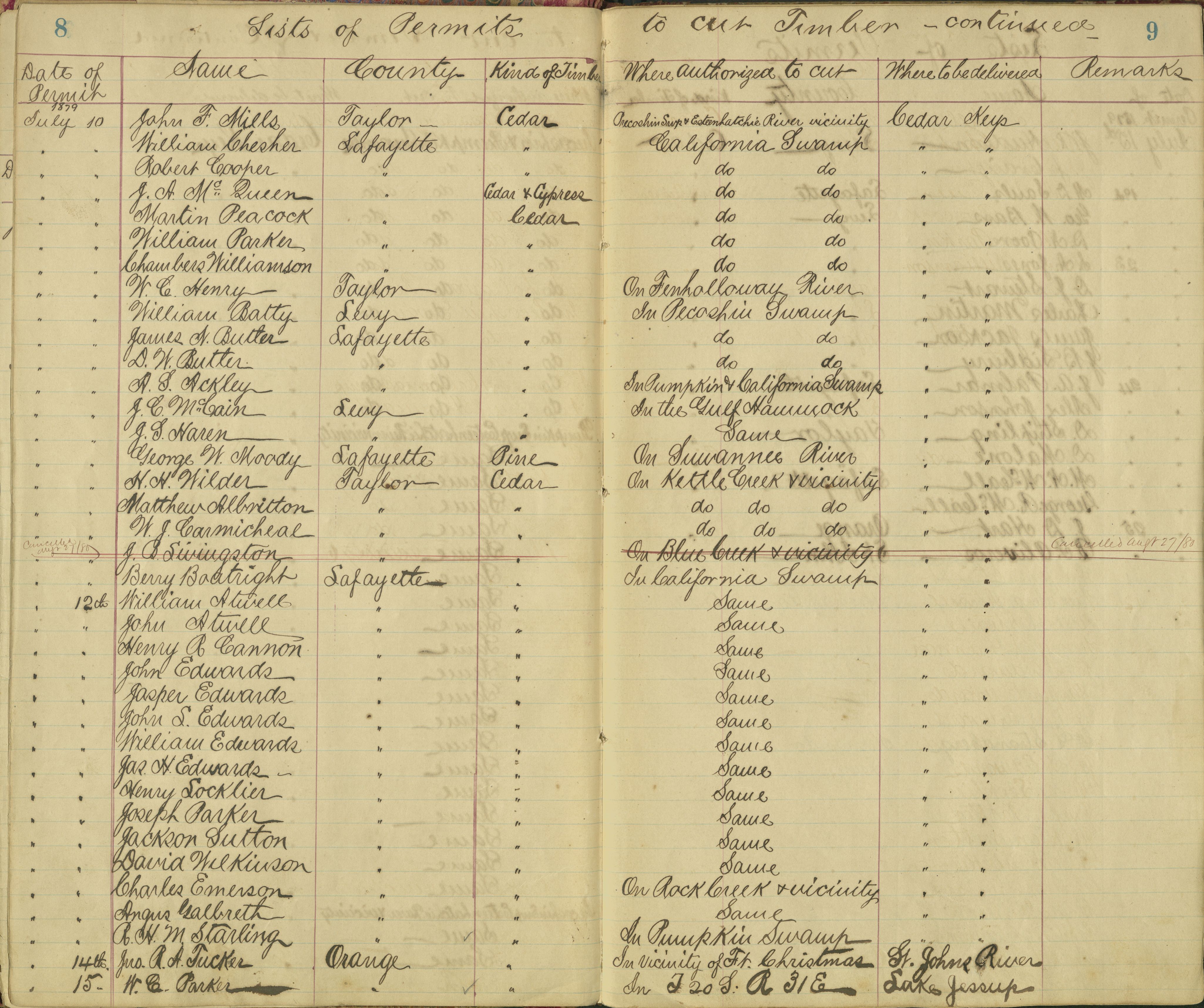

Once the permit was issued, the Commissioner of Lands and Immigration entered the data into the ledger in the manner shown below. Here’s where the genealogical significance comes in. These records not only describe where the timber was being cut, but they also show where the timber cutter lived. In doing so, the records pinpoint the specific location of specific people at specific times–a very helpful data point for family history research. Even better, many of the applicants for timber cutting permits were farmers whose activities would not have been documented in many other records, especially not in the late 19th century. If you were to find an ancestor listed in this ledger, you would have not only a data point showing where the person was living at a certain time, but also some insight into how they made their living in the 1870s and 1880s.

Example page from a register of timber permits (Series 1814, State Archives of Florida). Click or tap the image to view the entire book.

These records cover a short period of time and a limited number of people, but they’re an excellent example of why the State Archives of Florida is an essential part of the genealogist’s toolkit when tracing family history in the Sunshine State. Sources like these can be combined with other records to help you form a more complete picture of who an ancestor was and what they did during their lifetime in Florida.

Got a question about the many records we have at the State Archives? Email the Reference Desk at Archives@dos.myflorida.com, or give us a call at 850-245-6719.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Sawing Logs." Floridiana, 2019. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342050.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Sawing Logs." Floridiana, 2019, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342050. Accessed March 5, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2019, January 1). Sawing Logs. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342050

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program