Description of previous item

Description of next item

Boom and Bust in Boca Raton

Published May 5, 2019 by Florida Memory

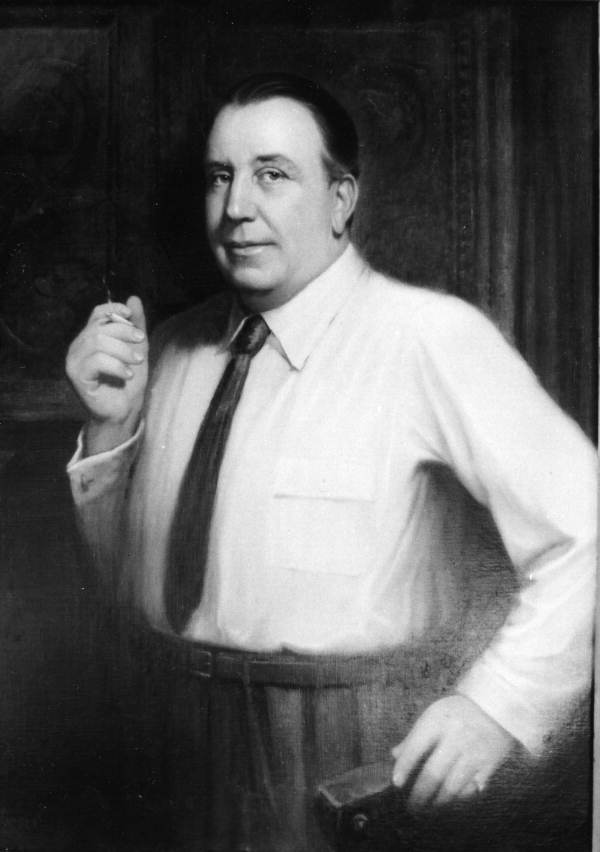

Addison Mizner is in many ways the personification of the great Florida real estate boom of the 1920s. He was a gifted architect with a knack for mixing Old World charm and fashionable opulence, a style he incorporated into a wide variety of buildings in Palm Beach and Boca Raton. He was also a real estate developer, prone to the same excesses that characterized land sales and promotion in those days. For a brief period in the mid-1920s, he was at the center of everything bright and hopeful about Boca Raton, his “dream city” as he called it. Shortly thereafter, he was also at the center of one of its worst setbacks.

Mizner was born into a prominent family near San Francisco in 1872. In 1889, his father was appointed U.S. minister to the Central American states, which took the family to Guatemala City. Young Addison developed a keen interest in the Spanish architecture that surrounded him, which would later find expression in the buildings he designed. In those days, architects generally got their training through apprenticeships rather than formal degree programs, and Addison Mizner learned the ropes by working under Willis Polk of San Francisco. He eventually set up a firm in New York City that provided both architectural services and a supply of Spanish artifacts he had purchased from Europe and South America.

Business slowed to a crawl during World War I, and a combination of family and health problems did nothing to help Mizner’s situation. In 1918, however, he received a fateful invitation from Paris Singer (son of the famous and wealthy sewing machine manufacturer) to visit Palm Beach to recoup. While there, Singer and Mizner would often walk along the beach, which in those days was almost completely undeveloped. Mizner would conjure up grand visions of Moorish towers and cool, shaded courtyards–enticing enough that Singer actually bought up property and asked the architect to try to bring some of these ideas to fruition.

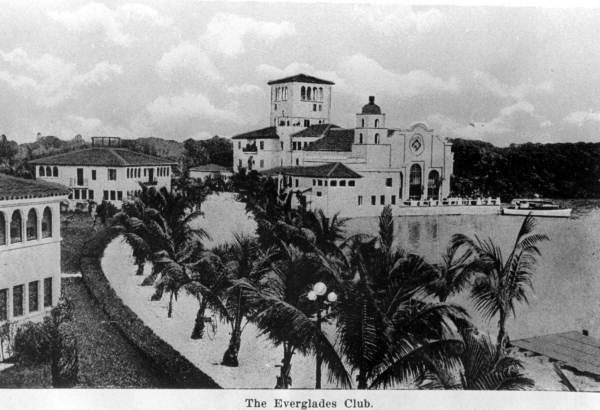

Mizner’s first building in Palm Beach, the Everglades Club, was a resounding success. Originally intended as a convalescent home for wounded soldiers and sailors, the proposed building morphed into a sumptuous resort once the war ended. Mizner had trouble finding workers who could make the kinds of tiles and ironwork his designs called for, but in a pinch he would step in and teach the men himself, to the amazement of local observers. The club opened in 1919 and quickly sold 500 memberships at premium prices. James Deering, Joseph P. Kennedy, Henry C. Phipps, and others among America’s rich and powerful were early members, with Paris Singer as president. Having seen the grandeur and exoticism of Mizner’s designs, Palm Beach’s upper crust began calling on him to build fashionable homes for them. Between 1919 and 1924, the architect built more than 30 grand houses in the area, becoming a millionaire in the process. He established his own works for producing the tiles, furnishings and replicas of ancient artifacts that were key to his Mediterranean style.

Home of Dr. Preston Pope Satterwhite in Palm Beach, designed by Addison Mizner and completed in 1923 (photo ca. 1928).

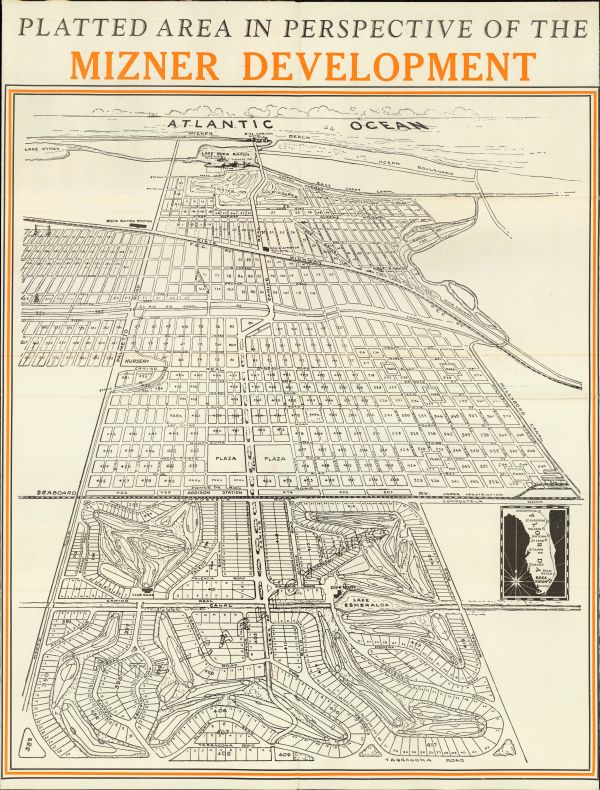

Mizner’s fame in Palm Beach grew with each new creation, but he had his mind set on a much more profound project located just down the coast. On May 5, 1925, the newspapers reported that a new company, the Mizner Development Corporation, would soon build a fabulous new Ritz-Carlton hotel in Boca Raton, flanked by villas, gardens and golf courses. This puzzled local observers, since Boca Raton was only a small farming community at this time, but Mizner quickly let them in on what he was thinking. The village would become “the first tailor-made city in all the world,” according to the advertisements. Everything from the streets to the waterways and landscaping would be harmonized into one seamless, coordinated paradise reserved for the rich and powerful. This would require land, of course, so Mizner’s company bought up two miles of frontage on the Atlantic Ocean and 1,600 acres of adjoining inland property. Money would be necessary as well, and Mizner had it, thanks to the connections he had made in Palm Beach. Senator T. Coleman du Pont of Delaware, the Vanderbilts, the Duchess of Sutherland, steel magnate Henry Phipps of Pittsburgh and Congressman George Graham of Philadelphia were some of his most prominent investors.

Map showing the grand vision for Addison Mizner’s development project at Boca Raton, with the Atlantic Ocean at the top of the map (1925). This map was included in an elaborate promotional brochure. Click or tap the image to view a larger version of the map and the complete brochure.

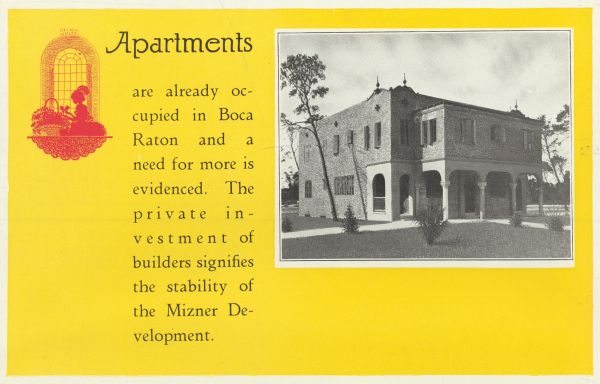

Construction began in 1925, and the little town of 100 souls quickly ballooned to more than 2,000 as builders and real estate salesmen came to transform Boca Raton according to Mizner’s vision. One of the first facilities to go in was the Camino Real, a grand boulevard 219 feet in width, with 20-plus lanes and extravagant landscaping. The Mizner Corporation’s administration building went in next at the corner of the Dixie Highway and the Camino Real. It was both a place of business and a work of art, its design inspired by El Greco’s house in Toledo, Spain. More than 40 homes were built, most in what is now called the Floresta section of town. Mizner also designed Boca Raton’s city hall, an airport, two golf courses and a church in which he installed his brother, an Episcopal minister.

Mizner Development Corporation bus in Miami. These buses left Miami every day to take prospective buyers on a tour of Boca Raton and convince them to buy a lot (1925).

Mizner and his associates coupled this feverish construction with equally enthusiastic advertisement, to the tune of millions of dollars’ worth of print ads and brochures. This, plus widespread recognition of the Mizner name for his work in Palm Beach, generated some astounding early sales numbers. The Mizner Development Corporation sold $14 million in lots the first day they were on the market. Within six months, the company had cleared $26 million in cash payments, and that was just the down payments.

Real estate men working quickly in a Boca Raton office. When the Mizner Development Corporation first opened up Boca Raton for sale, his agents often worked late into the night processing paperwork for the sales (1925).

But there was trouble in paradise lurking just beneath the surface. Like so many real estate developments during the Florida boom, the financial underpinning of Mizner’s grand scheme for Boca Raton was risky at best, and some parts were even illegal. The corporation was making money, but it was also spending money–fast. To raise additional capital, Addison Mizner and his brother Wilson would sometimes buy up stock in local banks and then take out loans from those same banks, putting their directors on the board of the Mizner Development Corporation to ensure they would benefit from the proceeds of their loans.

One panel from a Mizner Development Corporation brochure published around 1925. The company frequently referred to its list of well-known investors to inspire confidence in the enterprise. Click or tap the image to view the entire brochure.

Then, in the fall of 1925, Mizner took a step that proved to be one step too far. Well before ground had even been broken on some of the largest and most expensive components of the Boca Raton development, Mizner’s company began attaching a “Declaration of Responsibility” to the bottom of its advertisements. “Attach this advertisement to your contract for deed,” the addendum read. “Every promise made by the developers of BOCA RATON is made to be fulfilled, and this caption is your protection.” Essentially, the company was guaranteeing that all parts of the proposed resort town would be completed as planned, and that lot buyers would make a large profit on their investment. This had a nice ring to it, of course, but it also exposed the corporation and its backers to tremendous liability. When he found out about this, Senator duPont (still chairman of the board) was outraged and demanded the resignation of Wilson Mizner and Harry L. Reichenbach, the public relations man who had come up with the so-called Declaration of Responsibility idea. When these demands went unheeded, duPont resigned from the board. Addison Mizner handled the defection badly, and in the process of defending Wilson he managed to drive off four more directors from the board in the space of a week. These events were very widely discussed in the press, and the negative publicity began to have a chilling effect on sales.

Boca Raton real estate office on Ocean Drive. With the boom in danger, many of the surrounding lots would go unsold for years (1925).

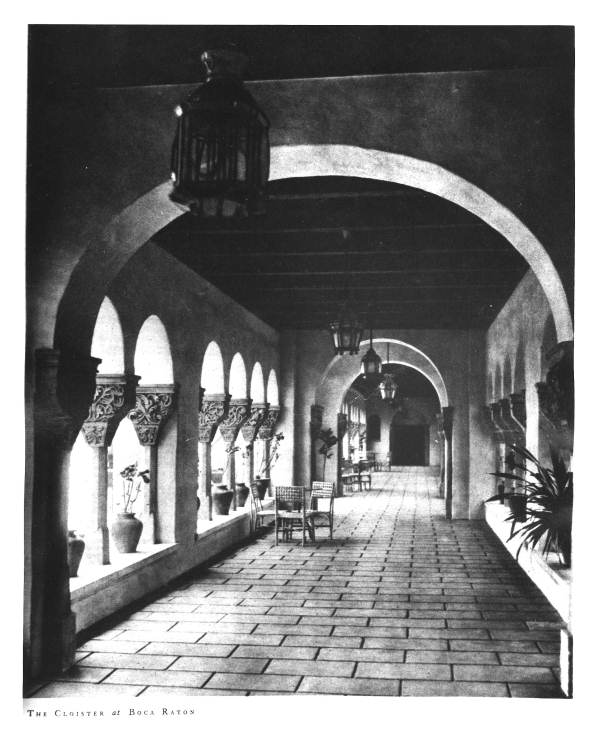

Addison Mizner would have one more glittering triumph before these events really caught up with him. On February 6, 1926, the Cloister Inn opened in Boca Raton with exquisite fanfare. The Cloister was the smaller of the two resorts included in Mizner’s grand plan, having “only” 100 rooms, but it was still a masterpiece. It featured vaulted ceilings, 14-karat gold leaf columns and luxurious furnishings and appointments that earned it a reputation for being the most expensive 100-room hotel ever built. The banquet celebrating its opening was a popular social event for America’s upper crust. “Royalty, Wall Street wealth, the most famous film stars of the day and the ranking hierarchy of Palm Beach and Bal Harbor rubbed shoulders in the throng,” historian Henry Kinney later wrote of the event, calling them “jeweled to the hilt and furred to the teeth.”

The celebration was short-lived. The drop-off in sales after the brouhaha with the board never reversed, and in fact it indirectly exposed other real estate developments to scrutiny and helped burst the broader Florida real estate bubble. Mizner’s businesses went bankrupt, and many of his greatest plans for Boca Raton never made it past the drawing board. He returned to his architectural practice for a few years until poor health forced him into inactivity, followed by his death in California in 1933.

Despite the overall failure of Mizner’s Boca Raton project, some aspects of his opulent vision still anchor the architectural landscape of the community today. Shortly after the Mizner Development Corporation collapsed, the Cloister Inn ended up in the hands of Philadelphia financier Clarence Geist, who added a few features to the hotel and converted it into the Boca Raton Club. Waldorf Astoria Hotels and Resorts now operates the resort. Many of the houses and other buildings Mizner designed also still remain, both in Boca Raton and Palm Beach. Their charm is matched by their historic significance as artifacts of the tumultuous Florida boom.

Try searching the Florida Photographic Collection on Florida Memory for more early photos of Boca Raton, and check out these resources to learn more about Addison Mizner and his grand development schemes in South Florida in the 1920s:

Jacqueline Ashton. Boca Raton Pioneers and Addison Mizner. Boca Raton: J. Ashton Waldeck, 1984.

Caroline Seebohm. Boca Rococo: How Addison Mizner Invented Florida’s Gold Coast. New York: Clarkson Potter, 2001.

Raymond B. Vickers. “Addison Mizner: Promoter in Paradise.” Florida Historical Quarterly 75, no. 4 (Spring 1997): 381-407.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Boom and Bust in Boca Raton." Floridiana, 2019. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342056.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Boom and Bust in Boca Raton." Floridiana, 2019, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342056. Accessed February 24, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2019, May 5). Boom and Bust in Boca Raton. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342056

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program