Description of previous item

Description of next item

Using Tax Rolls for Family History Research

Published June 6, 2019 by Florida Memory

You’ve probably heard the tired old cliché that nothing in life is certain except for death and paying taxes. Roll your eyes if you must, but if you’re researching your family tree, you can make this reality work in your favor! Tax records are probably one of the most sorely underutilized resources in the genealogist’s toolbox. Much like census records, they provide lists of people living in a specific place at a specific time, with the added bonus that they’re created every year instead of every decade like the federal census. Moreover, they contain all sorts of information about each taxpayer’s property and occupation–anything that was being taxed at that time. Government officials used the information to determine how much to charge each citizen in taxes, but you can use it to help reconstruct an ancestor’s life and household.

The most commonly available tax record is the annual tax roll, a list of all the taxpayers (or their agents) in a county and a table showing the various kinds of property and activities they were taxed on for the year. Today’s tax rolls deal almost exclusively with real estate, which is certainly helpful, but the most descriptive rolls come from the early to mid-19th century because in those days the county tax assessor was responsible for collecting taxes on everything from land to professional licenses to household property.

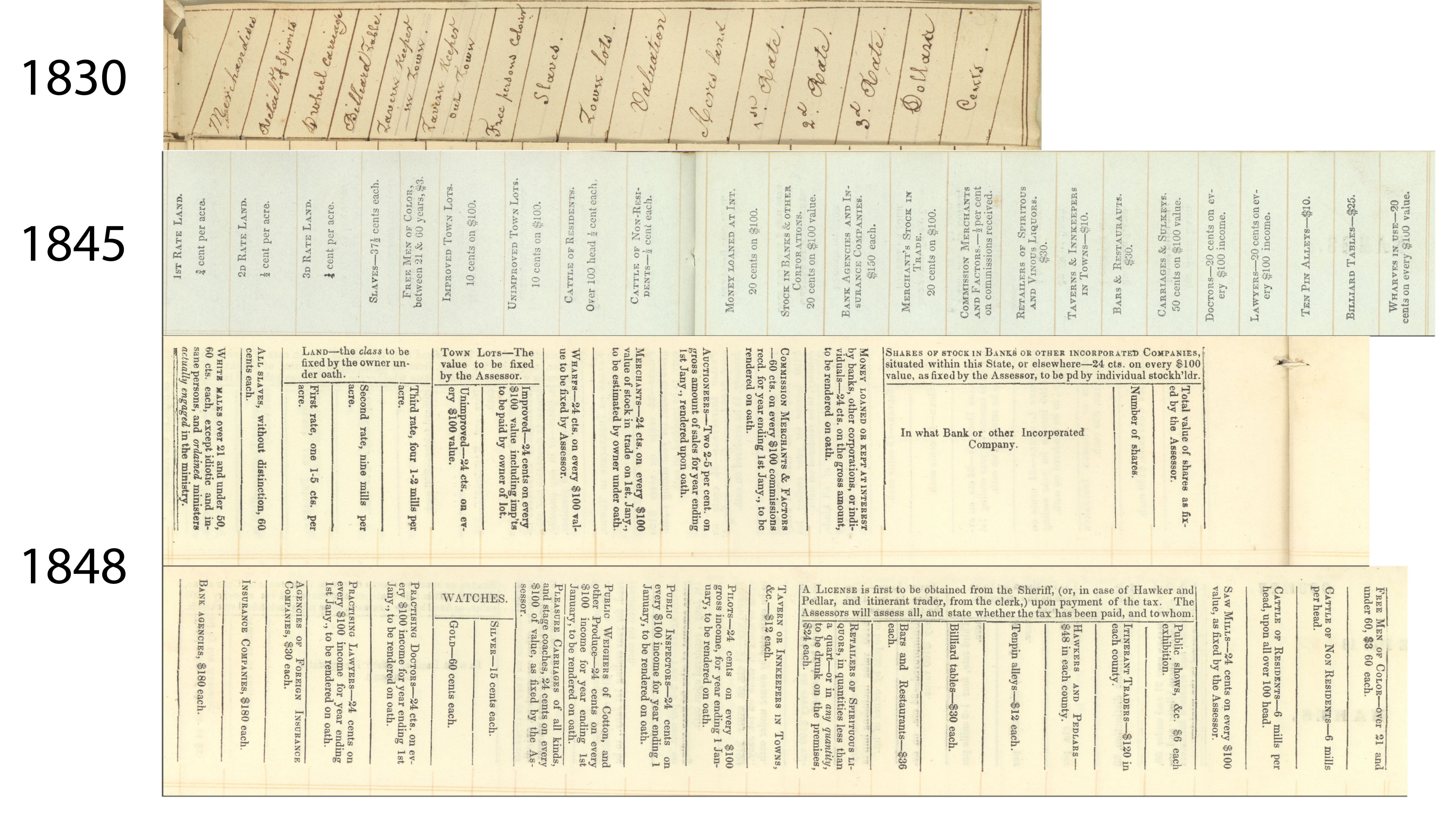

Just like today, early county tax assessors would receive guidance from the state on how to calculate the taxes for the year, plus the necessary forms. He would then take inventory of the taxable property belonging to each head of household in the county. The tax collector would then be responsible for collecting the revenue. Sometimes the positions of tax assessor and tax collector were combined, and sometimes the county sheriff acted as both. No two tax rolls are exactly alike, even for the same county–the tax rates change from year to year, as do the categories of property and activity that were being taxed. Take a look, for example, at the column headers from these three tax rolls from St. Johns County:

This graphic shows the column headers from three 19th-century tax rolls from St. Johns County. Compare the headers to see how taxation changed over time. Tax Rolls (Series S28), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

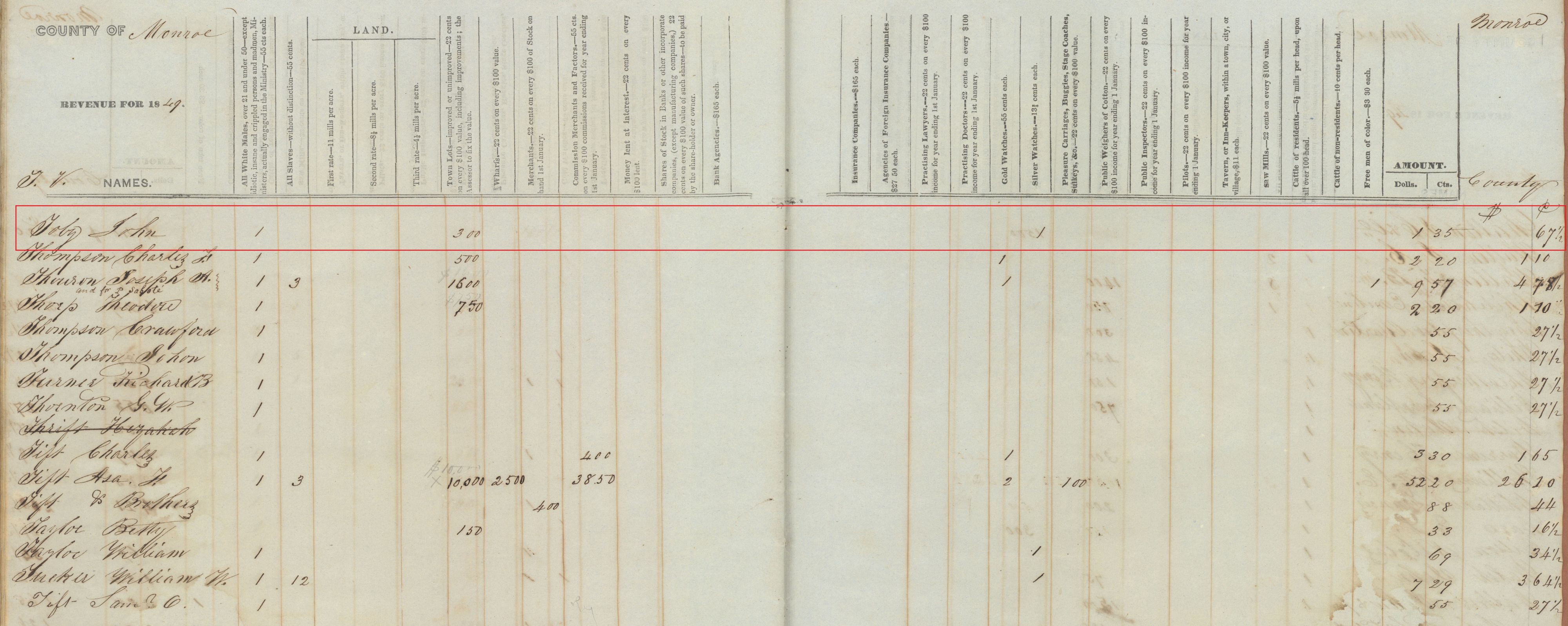

So what can you do with these records? One of our favorite uses for tax rolls is to get a better sense of when exactly someone moved into or out of an area. Take John Toby of Monroe County, for example. John shows up in the 1850 federal census as a butcher living in Key West, but he’s missing from both the 1840 and 1860 censuses, and we haven’t yet been able to positively match him up with any of the other John Tobys who appear in records from other parts of the United States. John does, however, show up in multiple tax rolls from Monroe County on either side of 1850. By looking through the Monroe County rolls, we can get a better sense of when he arrived in Key West and when he left.

Excerpt from the 1849 tax roll for Monroe County showing an entry for John Toby. Tax Rolls (Series S28), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

Looking through the tax rolls, the first time we see John Toby in Monroe County is in 1846. He didn’t have much at the time–no real estate, just one silver pocket watch. If his 1850 census listing is to be trusted, he was about 31 years old then. Moving forward in the records, we see him in the tax rolls for each year after 1846 through 1859. He does not, however, show up in the 1860 tax roll or any other roll thereafter, at least not for Monroe County. We can reasonably guess, then, that he lived in Key West from about 1846 to 1859, and then either died or moved someplace else. When a man dies, his name usually still appears on the tax roll for a year or two afterward while his estate is being settled, or sometimes his wife will appear on the tax roll instead as head of household. In John Toby’s case, neither of these occurred, so we can infer that John and his wife Mariam moved away from Key West around 1859. It’s no silver bullet, but this information could help us match our John Toby up with other John or Mariam Tobys that occur in other records, even if they don’t specifically refer to Key West.

An excerpt from an 1859 Monroe County tax roll showing John Toby once again, this time with much more property than he had ten years before. Tax Rolls (Series S28), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

Another useful feature of tax rolls is their ability to show us how families change over time. Using John Toby once again as an example, we can follow his taxpaying years in Key West and see how his wealth and property grew the longer he operated his business. When he first appears on the tax rolls in 1846, he was only charged a head tax for himself and a small tax on his silver pocket watch. The next year, however, he was also taxed for a town lot valued at $200. By 1850, the assessed value of John’s town lot had increased to $300 and he owned one slave. He seems to have sold or lost the slave soon after that, but in 1856 he was taxed for a carriage or cart worth $20, horses and mules worth a total of $40, $50 worth of household goods and that same silver pocket watch, which was valued at $10 that year. Business must have been picking up for John, because the following year (1857) he had at least one slave valued at $300, and by 1859 he had two slaves with a total value of $1000 (see the excerpt from the 1859 tax roll above). These are small details, but when we look at how John Toby’s taxable property changed over time and combine that information with what we know from his 1850 census record, we start to get a clearer picture of what his life was like in Key West. It also gives us a sense of what kind of person we should be looking for when we search for John or his wife Mariam in other records.

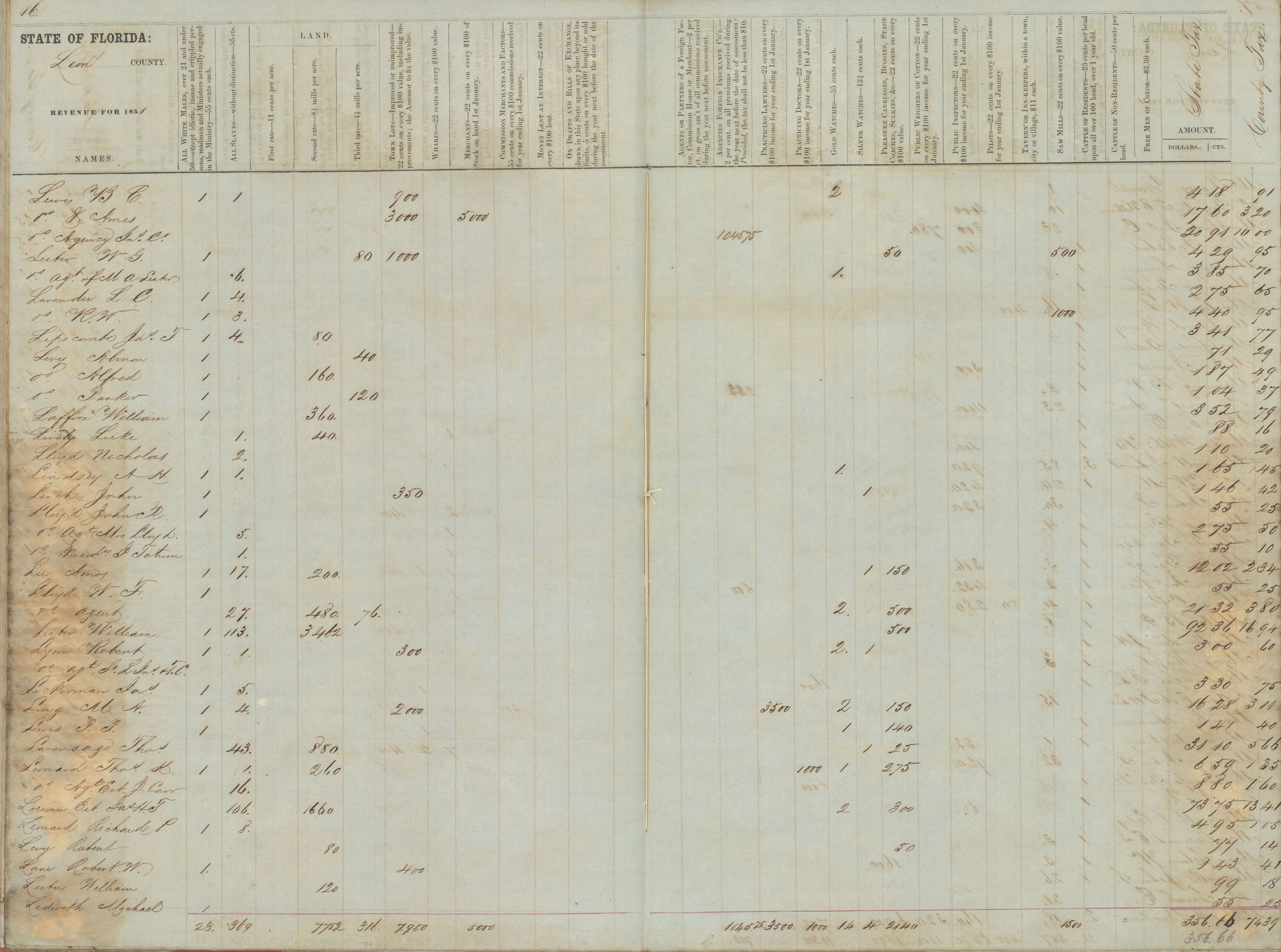

Another valuable feature of 19th century tax rolls is the information they can provide about an ancestor’s occupation. For many years, license taxes were reported on the tax rolls, which means you can quickly scan to see who all of the doctors, lawyers, merchants and other professionals were in a given county in a given year. Other occupations can be determined by looking at a person’s taxable property. If someone was being taxed on a sawmill or $2,000 in cattle or $5,000 in merchandise, for example, you can safely guess at least part of what they were doing for a living. We can see lots of occupations represented in this excerpt of the 1851 tax roll from Leon County:

Excerpt of the 1851 tax roll from Leon County. Tax Rolls (Series S28), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

One final feature that you may find useful is the tabulations page at the end of each year’s tax roll. One of the roll’s most important functions was to determine how much tax revenue the county would receive that year, as well as how much the county had to remit to the state. At the end of each roll, the tax assessor would write up a summary with totals for each category of taxation for the entire county. This is a great way to track how many people there were in certain occupations in a county at a given time, the total number of slaves, the value of land, etc. Here’s an example of one of those tabulation pages from Escambia County in 1854:

Data from the tabulation page of the 1854 Escambia County tax roll. Tax Rolls (Series S28), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

So where do you find these tax rolls? The State Archives of Florida holds a fairly large–though by no means exhaustive–collection of these documents for the early to mid-19th century. They have not yet been digitized, but they are open for public research. Also, if you know the specific tax roll you need, you can contact the State Archives’ reference staff at archives@dos.myflorida.com to request copies of the entire tax roll for a specific county in a specific year, or just the page with a specific person on it. Reproduction fees may apply; see our fee schedule for details. To see which tax rolls we have for the counties that interest you, visit the catalog record for Series S28 in the Archives Online Catalog. From that page, click the yellow folder icon to display a box listing of the tax rolls we have available in that series of records. The records are arranged alphabetically by county and then chronologically.

Counties also sometimes hold copies of tax rolls from the early to mid-19th century. Depending on the county, older tax records may be retained by the clerk of the courts, the tax collector or the property appraiser.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Using Tax Rolls for Family History Research." Floridiana, 2019. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342058.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Using Tax Rolls for Family History Research." Floridiana, 2019, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342058. Accessed February 24, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2019, June 6). Using Tax Rolls for Family History Research. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342058

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program