Primary Source Set

Prohibition in Florida

Prohibition refers to the concept of legally banning the sale or manufacture of alcoholic beverages. As early as Florida’s territorial era (1821-1845), religious leaders and other activists encouraged temperance, or abstinence from the use of alcohol and other intoxicants, as a way to protect families and reduce violence and social disorder. The early impact of this movement was small in Florida, although legislators did raise the license fees for businesses selling alcohol several times, hoping to limit the number of saloons.

The temperance movement gained more traction in the late 1800s. When Florida adopted a new state constitution in 1885, it included a rule allowing each county to decide whether it would permit the sale or production of alcohol. As a result, many counties held local option elections in which voters expressed their preferences on the matter. Temperance advocates were nicknamed the “drys,” while people who opposed alcohol restrictions were called the “wets.” By 1905, more than half of Florida’s counties had voted to go dry.

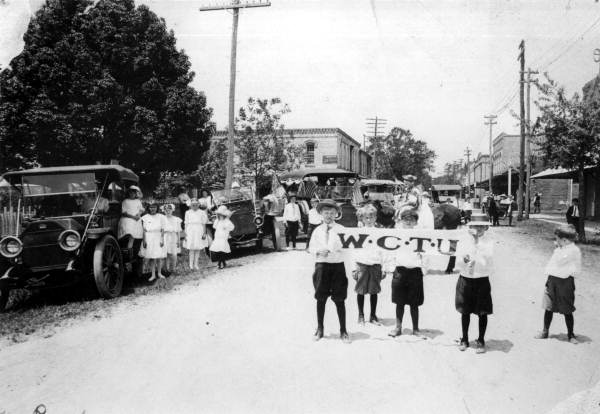

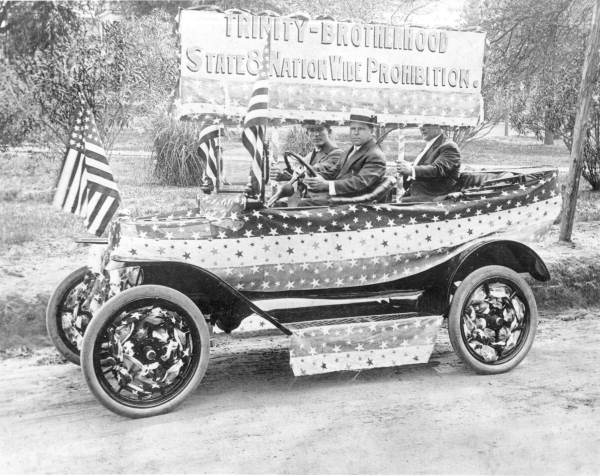

Meanwhile, activists all over the United States were calling for legislators to go beyond local option laws and ban the sale of alcohol completely. Two of the most influential groups favoring total prohibition--the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League--had large chapters in Florida. They gave speeches, held temperance parades and handed out flyers and pamphlets to voters, while also keeping steady pressure on lawmakers.

The first attempt at a statewide prohibition amendment failed at the polls in 1910, but prohibition advocates were gaining ground. By 1915, only a dozen Florida counties remained wet. When another proposed statewide prohibition amendment came up in 1918, the voters ratified it.

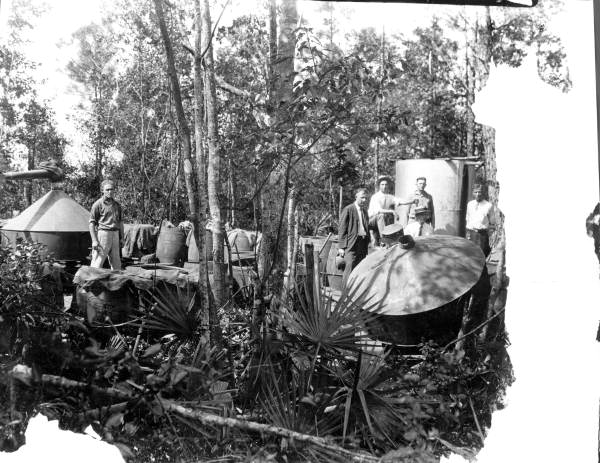

Florida’s decision to go dry statewide was followed by the ratification of the 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which banned the manufacture, sale and transportation of alcohol across the entire nation. There was still a demand for alcoholic beverages, however, and plenty of illegal alcohol made its way to market. “Rum-runners” took advantage of Florida’s many miles of coastline to bring it in from Cuba, the Bahamas and elsewhere. Many Floridians in the state’s rural interior made moonshine or other bootleg liquor and sold it to make extra cash. State, local and federal authorities all attempted to enforce the prohibition laws, but they were never able to fully stamp out these illegal activities.

By the early 1930s, many Americans considered Prohibition a noble experiment that had failed. It did not end alcohol consumption in the United States, but instead drove much of the activity underground. Rum-running, moonshining and organized crime all increased as a result. Also, as the Great Depression set in, opponents of Prohibition were able to argue that repealing the law would produce jobs and government revenue at a time when both were very badly needed.

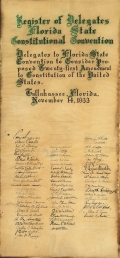

In 1933, Congress passed the 21st Amendment to the Constitution, which repealed the 18th Amendment that had established Prohibition. A convention of delegates selected by Florida’s voters ratified the amendment on November 14, 1933. The following year, Florida voters chose to also repeal the state’s separate prohibition law and return to the old local option system, which still remains in place today.Photo credit: Temperance parade - Eustis, Florida, ca. 1919.

(State Archives of Florida)Show full overview

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program