Primary Source Set

Florida and the Politics of Westward Expansion

Despite the state’s location on the eastern coast of the United States, Florida played an important role in the history of the nation’s westward expansion. Acquiring Florida from Spain would mean more land and natural resources, as well as economic opportunities, for U.S. citizens, and it would reduce the influence of other countries on the North American continent. White settlers in Georgia were especially eager for Florida to come under United States control, since they did not consider the Spanish to be very good neighbors. For many years, enslaved persons sought their freedom in Spanish Florida beyond the reach of U.S. authorities; Spanish colonial officials did very little to stop it. White settlers also complained that the Spanish took no steps to prevent Native Americans from crossing into U.S. territory, sometimes resulting in violent clashes.

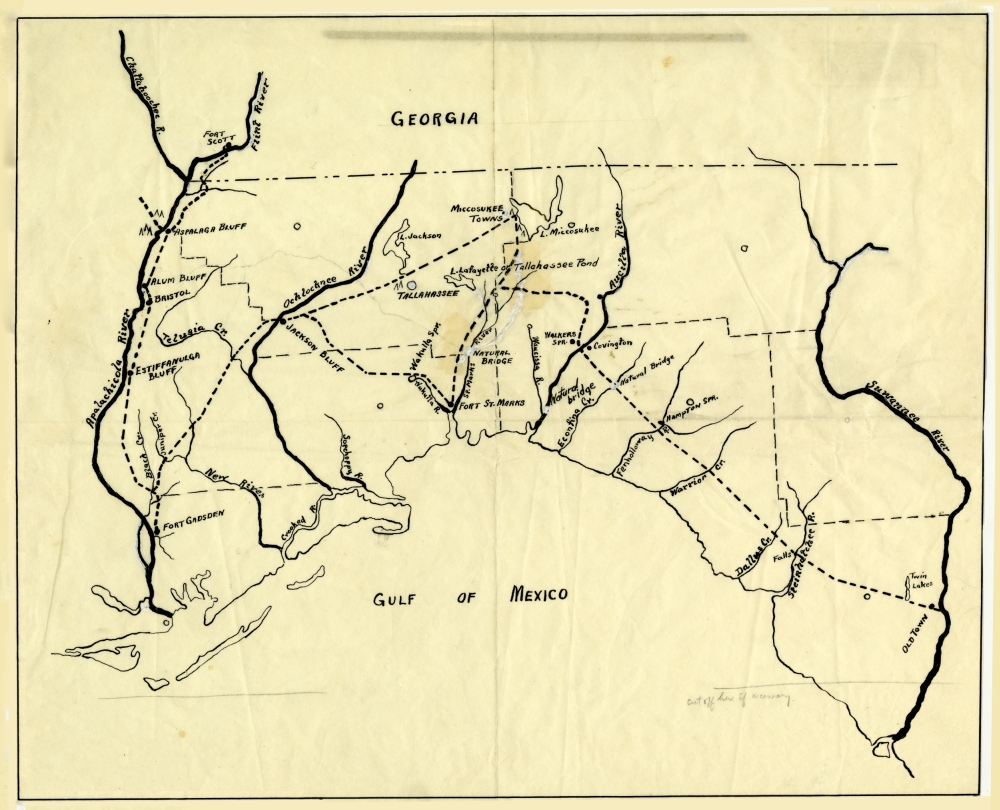

The matter came to a head in 1818, when the First Seminole War broke out. General Andrew Jackson crossed into Florida to pursue the Seminoles and ended up seizing Spanish forts at St. Marks and Pensacola in the process, hoping to force Spain to give up Florida. Spain complained about Jackson’s actions, but, facing a larger crisis of government at home in the wake of the Napoleonic wars, decided to strike a deal with the United States.

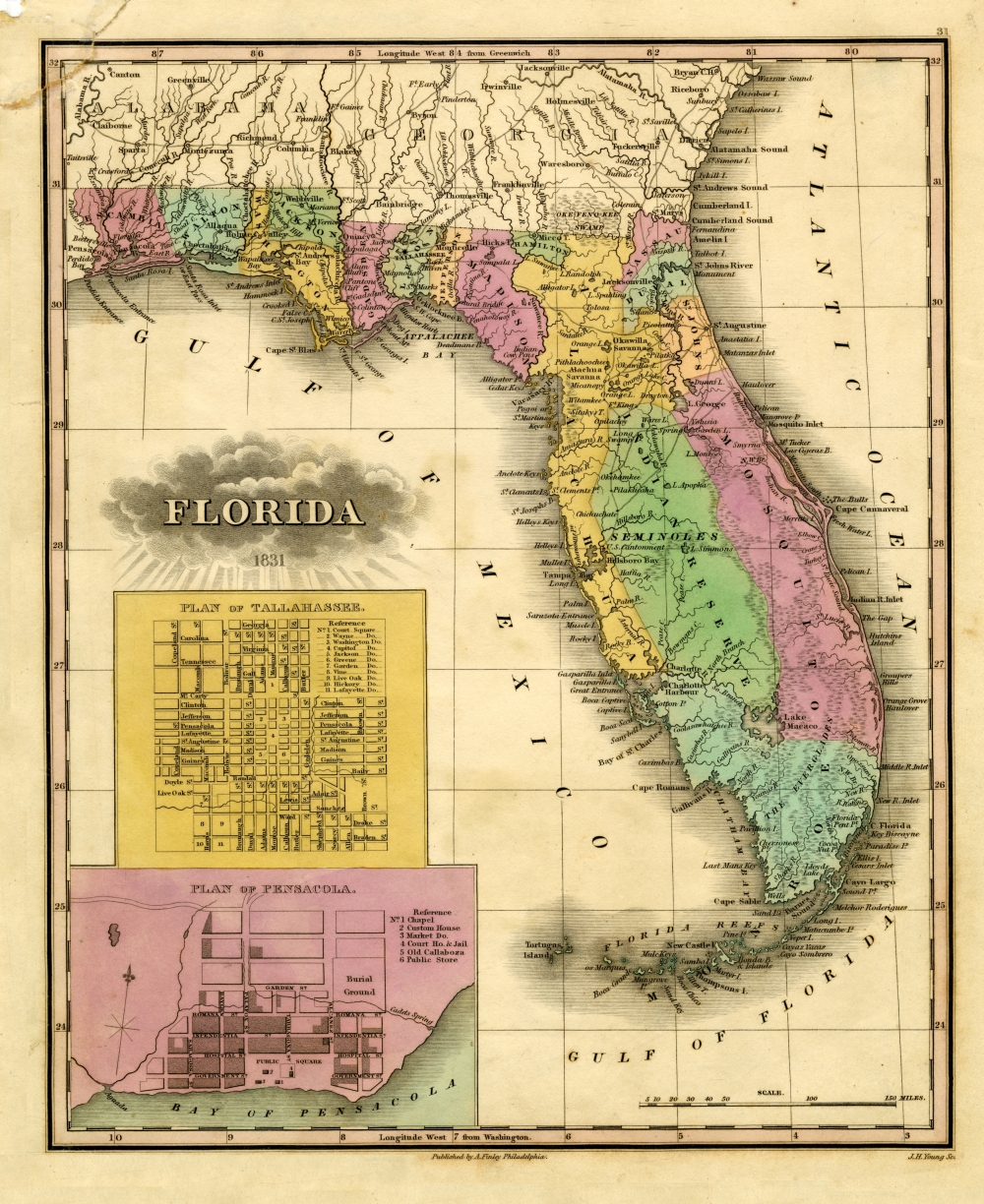

The Adams-Onis Treaty, ratified in 1821, settled several boundary disputes between the U.S. and Spain and transferred all of Florida east of the Perdido River to the U.S. The portion of West Florida between the Perdido and Mississippi rivers was already in U.S. hands and had been given to Louisiana and the new Mississippi Territory. The cession of Florida, plus the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, doubled the size of the United States.

There were still big issues left to resolve. The new land was far from empty—Native Americans had been living there for thousands of years. As white settlers migrated both westward and southward, they clashed with the native people they encountered. National leaders wanted to resolve the issue by forcing the Native Americans to move west of the Mississippi River, but many of the natives chose to stand their ground. This led to a long series of wars in Florida, including the Second Seminole War.

There was also the question of whether slavery would be allowed in the new western territories. When Missouri asked Congress to be admitted to statehood in 1819, representatives from northern, non-slaveholding states tried to add an extra provision outlawing slavery in the new state. Southern slaveholding states argued that the Constitution gave Congress no right to make such a restriction. The dispute ended in the Missouri Compromise of 1820, in which both Missouri and Maine became states. Missouri permitted slavery, while Maine did not, preserving a balance between slave states and free states in the Senate. Also, Congress drew a line across the entire Louisiana Purchase at 36°30′ latitude. Slavery was allowed in new states and territories established below the line, but not above it. This compromise kept the peace for a while, but the issue came up again during the Mexican War in the 1840s.

The United States gained a huge amount of new territory once the war ended, and Congress had to decide what to do with it. During one debate, a Democratic Congressman from Pennsylvania named David Wilmot proposed an amendment outlawing slavery in all of the new territory. The Wilmot Proviso did not pass, but it did spark more fiery debate over the power of Congress to restrict the institution of slavery. Southern slaveholding states threatened to secede over the issue. Florida, which by this time had been admitted to statehood, was no silent observer in this debate.

Speeches and resolutions from state leaders reveal how serious they believed this situation to be, and the dark future they envisioned for the Union if the debate over slavery was not resolved. The Compromise of 1850 aimed to satisfy all sides by admitting California as a free state and prohibiting slavery in Washington, D.C. while strengthening the federal fugitive slave law and paying the public debts of the new state of Texas. While the legislation passed and a crisis was momentarily avoided, the original disagreement had not been solved. Florida’s legislators warned in a resolution to Congress that if the Northern non-slaveholding states continued to try to restrict slavery it would cause the destruction of the Union. This prediction proved to be prophetic—the American Civil War broke out about 10 years later.

Photo credit: Map of Free and Slave-Holding States in the United States, 1857.

Show full overview

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program