Description of previous item

Description of next item

Fruit of the Vine: A Brief History of Florida Winemaking in the Late 1800s and Early 1900s

Published October 10, 2021 by Florida Memory

When you see a bottle of fine wine on the shelf in a store, where do you imagine it came from? France? Italy? Maybe California? These are all places we usually associate with winemaking, but it may surprise you to learn that Florida wineries produce more than one million gallons of wine per year. Now, granted, that number accounts for less than half of one percent of all the wine produced in the United States annually. Still, winemaking has played an interesting part in Florida history, especially in the 1800s, when government officials and incoming settlers alike hoped a robust fruit and vegetable industry would elevate Florida's economy and make it "the Italy of America."

Woman posing with a bottle of wine in deBary Hall, the Volusia County winter home of New York City wine importer Frederick DeBary, who also had fruit groves near Lake Monroe (1961).

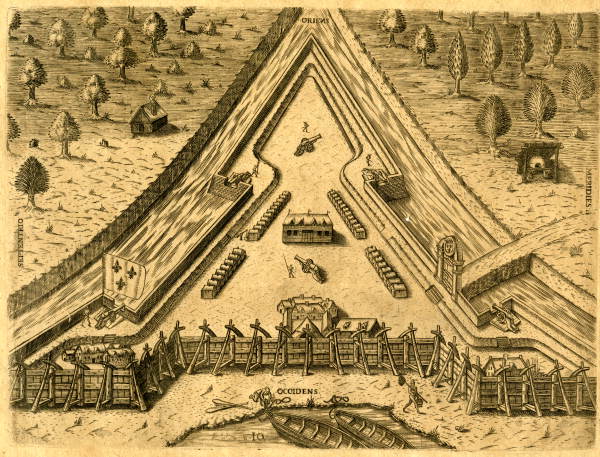

Archaeologists believe the Native Americans who inhabited Florida for thousands of years before the Europeans arrived ate grapes--wild muscadine grapes specifically. No evidence exists, however, to suggest that they cultivated the grapes or made wine from them. French colonists appear to have been the first Florida residents to try their hand at winemaking. René Goulaine de Laudonnière, a lieutenant of the French explorer Jean Ribault, established a colony of about 200 settlers in 1564 at Fort Caroline, located on the St. Johns River near present-day Jacksonville. One of the colonists noted in a letter that the settlers had found an abundance of wild grapes and that they hoped to make a supply of wine from them in the near future.

View of Fort Caroline published in a series of engravings by Theodor de Bry titled Grand Voyages in 1591. Click or tap the image for more information.

But the French didn't stick around in Florida for long. Spanish troops led by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés ejected the French from their fort and established their own settlement at St. Augustine in 1565. Franciscan missionaries also began establishing a series of Catholic missions to the north and west, hoping to Christianize the local Native Americans and make them allies of Spain in any future disputes with rival European empires. Here, winemaking reappears in the historical record. The missionaries appear to have cultivated grapes for making sacramental wines. When John Lee Williams of St. Augustine happened upon the site of Mission San Luis de Apalachee near present-day Tallahassee in 1823, he noted that trees and grape vines were growing in distinct rows, despite having been overtaken by other brush.

Except of a British map by Archer Butler Hulbert (circa 1750), showing the Old Spanish Trail and missions along its path. Click or tap the image for a zoomable version of the entire map.

Travelers during the Spanish colonial era noted grapes growing around the provincial capital of St. Augustine as well, although they wouldn't have been the Europeans' first choice for making wine. Europe's primary winemaking grape, Vitis vinifera, easily falls victim to insects and diseases in Florida, so winemakers would have had to resort to the hardier muscadine varieties. These grapes have made untold millions of gallons wine across the South over the centuries, but as wine connoisseurs will tell you, it's a completely different kind of product. It's often earthier and sweeter, mainly because of the sugar added when processing the grapes.

Scuppernong grapes, a common muscadine variety grown both commercially and for home use in Florida. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

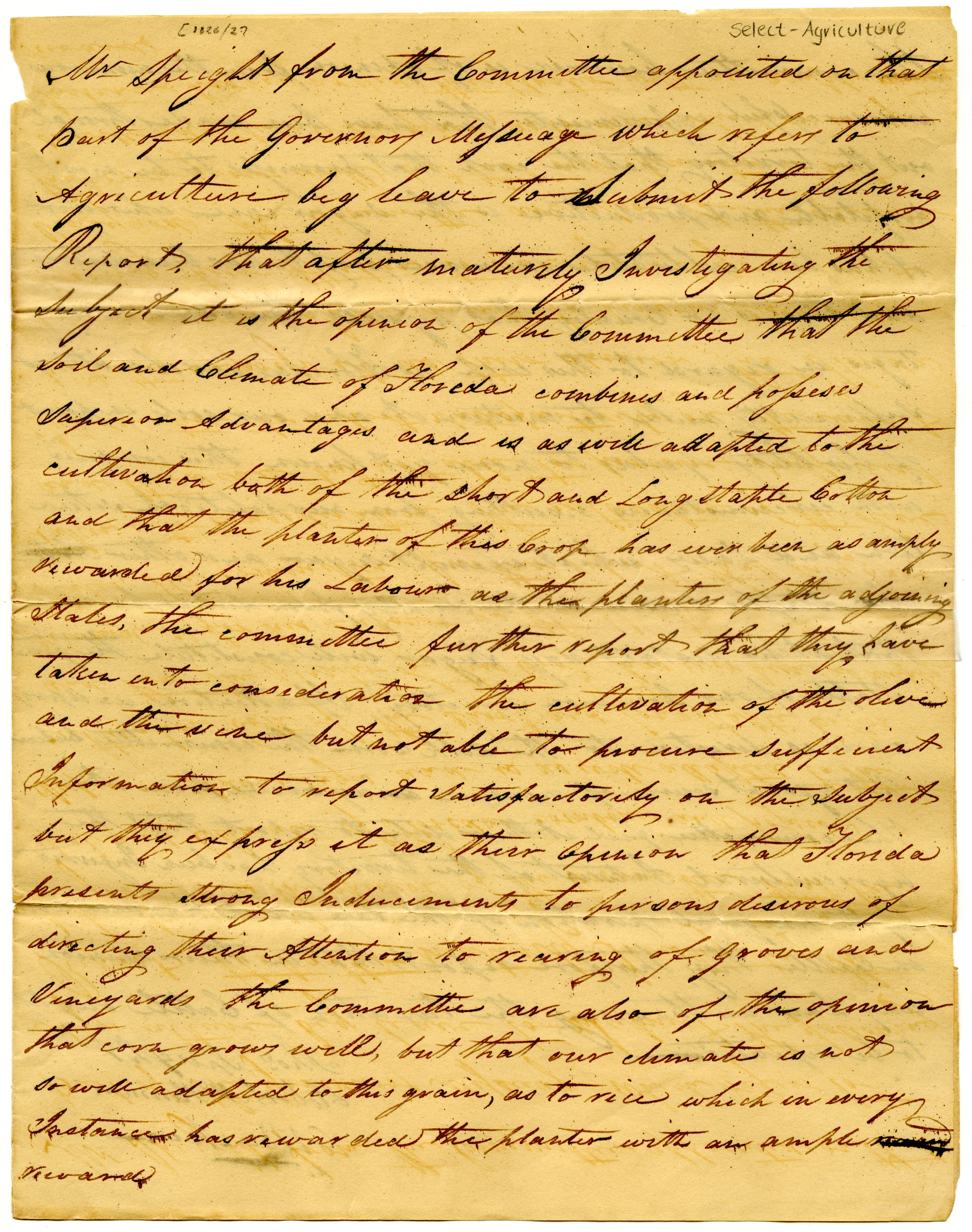

When Florida became a United States possession in 1821, one of the first priorities of the incoming settlers and their leaders was to determine which kinds of industries and agricultural products were best suited to the area. That would help the territory grow in wealth and population and eventually attain statehood. In 1826, in response to a request from Governor William Pope Duval, a committee of legislators reported on the agricultural potential of the territory, noting that Florida presented "strong inducements" for people who wanted to start groves and vineyards.

Excerpt from a report by a select committee of legislators on the agricultural possibilities for the Territory of Florida (1826). Click or tap the image to view a zoomable version of the entire report.

The idea of Florida becoming the next great wine-producing region was slow to take off. One of the most interesting attempts came in 1831, when a group of about 50 French peasants settled on a plot of land just east of Tallahassee at the invitation of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. Congress had voted to give the land to Lafayette as a token of the United States' appreciation for his services during the American Revolution. Lafayette didn't want to settle permanently in Florida, but he did hope he could establish a model colony that could farm the land profitably without enslaved labor. His colonists arrived with plans to establish vineyards and grow olives and mulberries, but their time in Florida was short-lived. Disease and other problems plagued the colony from the start, and most of the settlers left Florida within a year or two.

Better-established locals do not appear to have been very keen on growing grapes commercially. Census takers reported only 50 gallons of wine made across the entire state in 1850, and only 386 gallons in 1860. These figures are almost certainly lower than reality, but they're low enough to show that wine production hadn't gained traction like early legislators thought it might.

Wine consumption was another matter altogether. Store records at the State Archives of Florida indicate that customers were buying plenty of wine, along with other spirits, particularly whiskey. Take a look at this account from the store of Dowling and Rutgers in 1839. We've bookmarked a particular store account that shows several purchases of wine, but you can browse through the book to find other similar accounts:

Page from the accounts of a general store in Tallahassee operated by the firm of Dowling and Rutgers (1839). Click or tap the image to view a zoomable version of the entire account book.

The history of winemaking in Florida takes an upward turn after the end of the Civil War. With slavery at an end and sharecropping and tenant farming still in their infancy, large-scale cotton agriculture declined in the state. People still came to Florida from across the war-torn South and the northern states, but not to grow cotton. A few wealthier newcomers came to build railroads or hotels or mineral spring resorts. Others, often not as wealthy, came to start an orange grove or grow tobacco. And a select few, tantalized by glowing descriptions of the state's agricultural potential in guidebooks and the press, opted to establish vineyards.

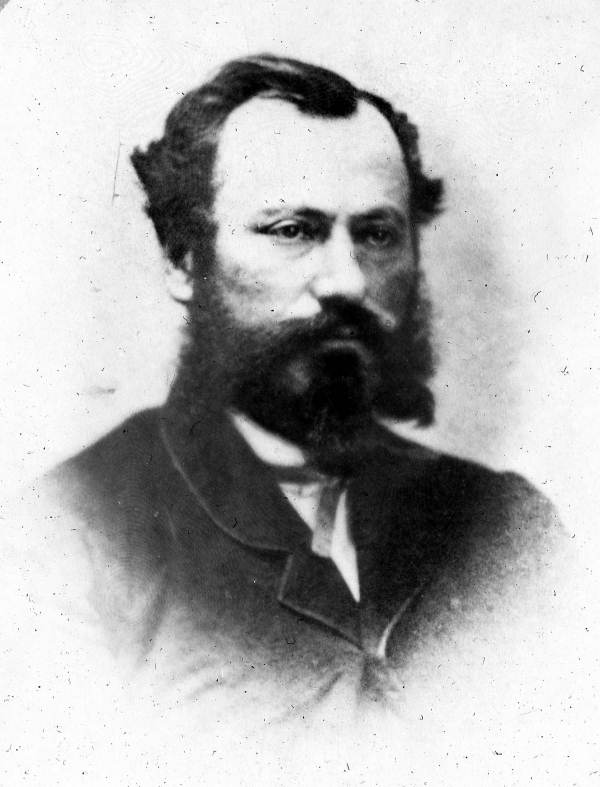

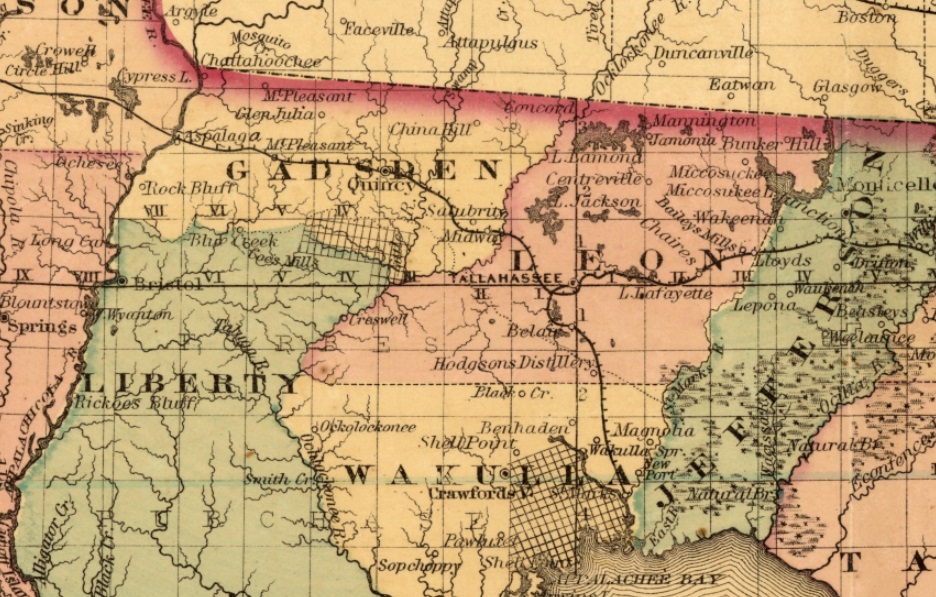

One such vineyard was started by Malachi Martin, an Irishman who had emigrated to the United States in 1847 and had been involved in the dry goods business in New York when the Civil War broke out. He volunteered for military service and worked his way up through the ranks as a quartermaster officer. Toward the end of the war he served in New Orleans and Key West, eventually landing in Tallahassee to serve as quartermaster for the Union troops occupying the state. After receiving his discharge in 1866, Martin rented some land intending to farm, but his early attempts were a failure and he quickly went into debt. He got a break in 1868 when the newly reconstructed state government established a state penitentiary at Chattahoochee and Governor Harrison Reed appointed him superintendent. With his cash flow problems quelled for the moment, Martin established a homestead east of Chattahoochee at Mount Pleasant and began raising crops, including scuppernong grapes. By 1874, he had gotten into the winemaking business. At that year's meeting of the Florida Horticultural Society, Martin bragged that he was producing wine at the rate of 2,000 gallons per acre and $2.25 per gallon. That would equate to $27.63 per gallon in today’s money, meaning Martin’s winery would be making more than $55,000 per acre annually. Whether those figures are correct or not, the operation wasn't entirely clean. A legislative committee in 1877 determined that on more than one occasion Martin had used prison labor to help tend his vineyard without paying the same rate other private business paid when they leased prisoners.

Excerpt of an 1876 map of Florida showing the location of Mt. Pleasant (where Malachi Martin had his winery) relative to Tallahassee and his workplace in Chattahoochee. Click or tap the image to view a zoomable version of the entire map.

About the same time Malachi Martin was planting his vines near Chattahoochee, A.J. Bidwell was starting his own vineyards near Jacksonville. Rather than relying on scuppernongs, Bidwell opted mostly for varieties derived from Vitis labrusca, also called the fox grape. He was especially proud of his Hartford Prolific grapes, which he said paid more than $300 per acre. He also mentioned Delaware, Greveling, Concord and Telegraph varieties in passing along advice to newcomers. Florida's big advantage in the wine industry, Bidwell said, was that its grapes would ripen sooner than those of northern producers. Early grapes from Florida could sell for as much as forty cents a pound (in the 1870s), whereas once the northern grapes ripened the price dropped to as low as ten cents.

Scenic view along the lake at Alfred B. Maclay Gardens State Park (1959). The gardens were once part of the Andalusia Plantation where John Craig, John Bradford and Emile DuBois all had vineyards in the 1800s.

In the Tallahassee area, nurserymen John A. Craig and John R. Bradford established a commercial vineyard at least as early as 1874. Craig's family estate--Andalusia Plantation--was located on Lake Hall a few miles north of town, and was planted with a wide variety of fruit trees. Census records from 1880 show that Craig had more than 500 apple trees producing more than 500 bushels of apples, along with two acres of peach trees producing 75 bushels of fruit. That's in addition to persimmons, plums, pears, figs and pecans, among other crops. Like Bidwell, Craig and Bradford focused on labrusca grapes, although they did grow other varieties.

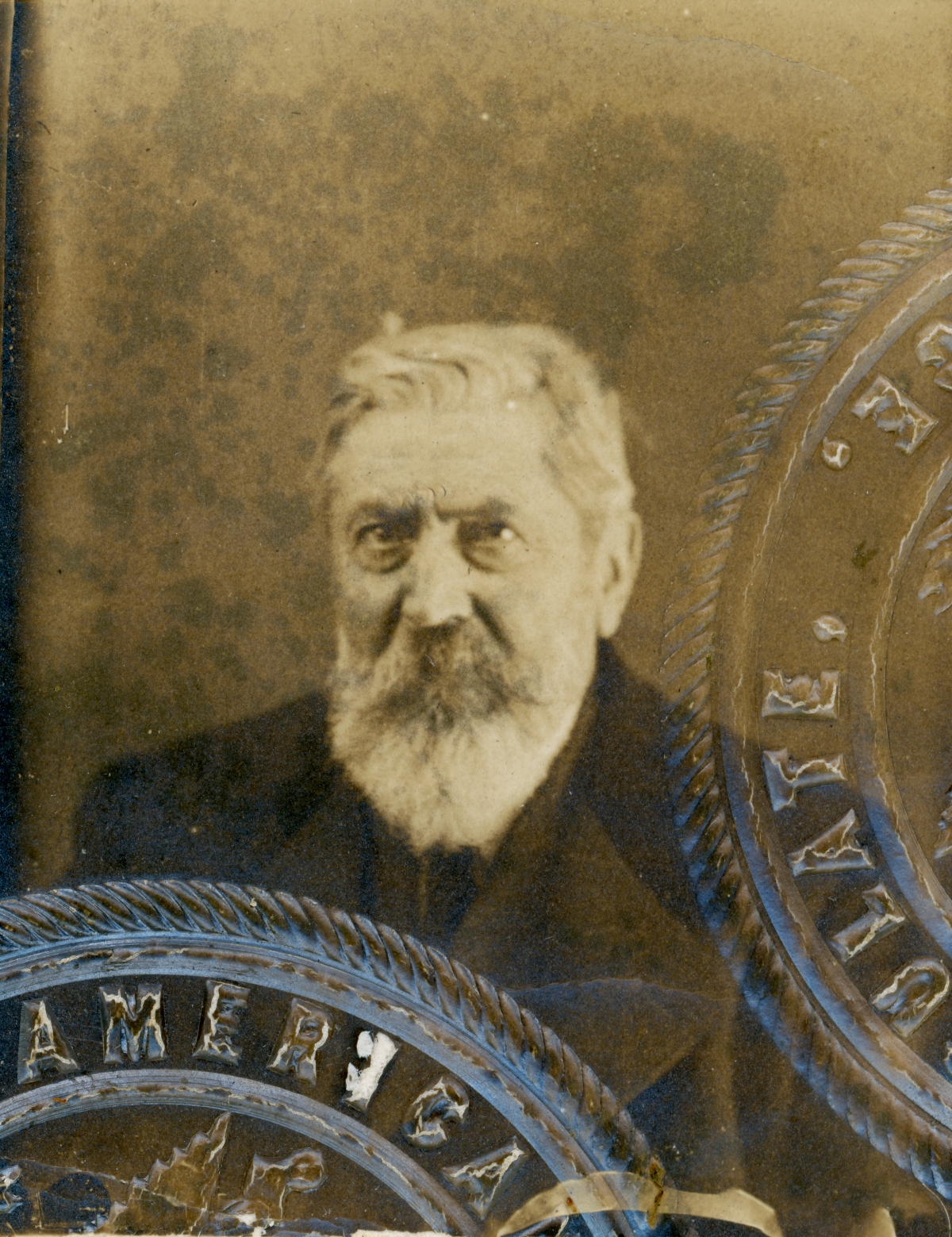

In 1882, Craig and Bradford sold a portion of the Andalusia Plantation to Emile DuBois, a French immigrant who came to Florida to test the region's capabilities as a grape-growing country. DuBois planted Elvira, Delaware, Cynthiana and a number of other varieties, choosing them based on which ones he found growing the best along roads and fences. Within a few years he was already making hundreds of gallons of wine, and he felt sure enough of his success to buy additional acreage. Appropriately, he selected a plot of land at the site of the old Mission San Luis de Apalachee, the same place John Lee Williams had seen evidence of grape culture when Florida first became a U.S. territory. DuBois named his new domain the San Luis Vineyard or Chateau San Luis, and quickly began setting out acres of new vines. By 1890, he was not only producing thousands of gallons of wine, but also shipping grape vines to newcomers in other parts of the state who hoped to duplicate his success. In 1889, judges at the Ocala Semi-Tropical Exhibition chose one of his wines as the best in Florida. A few years later in 1893, DuBois exhibited his claret, sauterne, haut-sauterne, hock, port and orange wines at the World's Columbian Exhibition in Chicago--the only Florida wines there. Whether they would have won awards is a mystery--DuBois did not enter them in any competitions because he was on the judging committee.

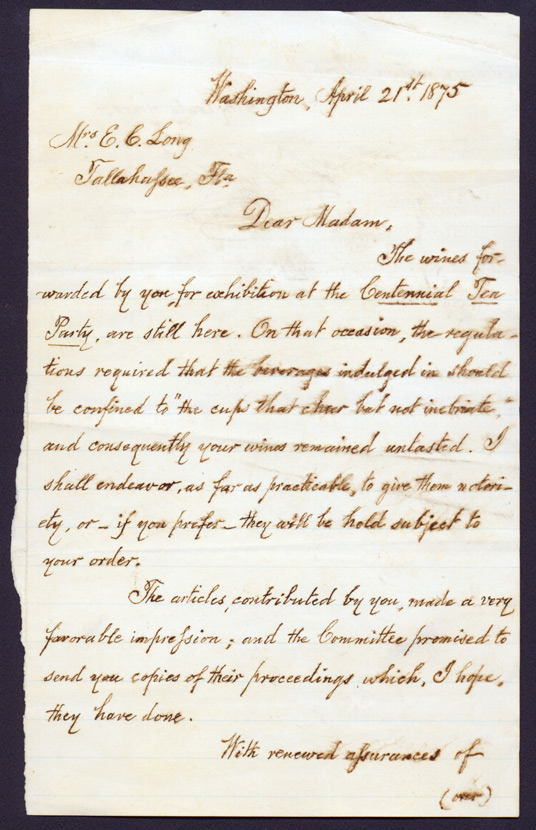

These are just a few of the vintners who produced wines in the late 1800s in Florida. The proceedings of the Florida Horticultural Society reveal the names of many more residents who experimented with growing grapes for wine, juice and table use. Such interest in wine and winemaking was far from universal, however. The temperance movement, which would eventually give rise to the nation’s short-lived experiment with prohibition, was gathering strength even as far back as the 1870s. One bit of evidence illustrating that trend materialized in 1874, when Ellen Call Long of Tallahassee sent a few cases of Florida wines up to Washington, D.C. to be used during an event to celebrate the centennial anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. Mrs. Long had been appointed Florida’s representative to the committee planning a whole range of centennial celebrations, and she felt this would be a good way to promote Florida’s potential as a wine-producing region. The wine was never served. One of the organizers wrote back and informed Mrs. Long that “regulations required that the beverages indulged in be confined to ‘the cups that cheer but [do] not inebriate.”

Letter from William Wilson Corcoran to Ellen Call Long, April 21, 1875, explaining that the Florida wines she had sent for the "centennial tea party" in Washington had not been consumed because the organizers had banned alcoholic beverages. Click or tap the image to view a zoomable version of the entire letter.

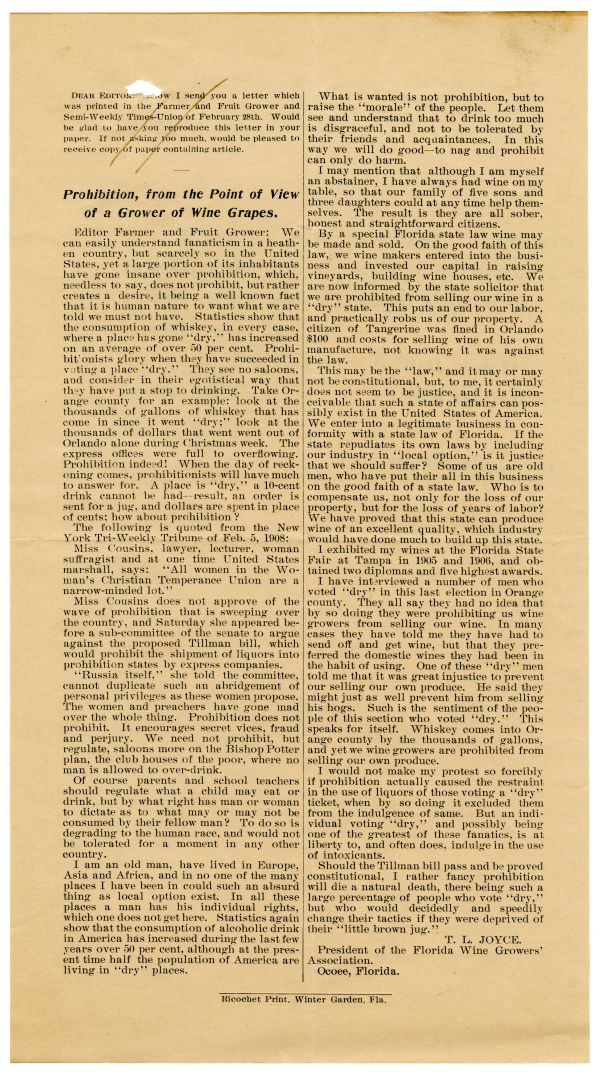

Florida had had temperance laws since the territorial era, but they became especially strict in the final decades of the 19th century. When the state’s new constitution was ratified in 1886, voters also approved an amendment allowing individual counties to decide whether intoxicating liquors, wines or beers could be sold within their boundaries. Many counties quickly held “local option” elections and chose to ban these beverages. These rules obviously posed a threat to the emerging wine industry, but winemakers first tried to make a case for Florida wine to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem. C.G. Frasch, a New Yorker who spent his winters tending a grove in the Orlando area, suggested in 1902 that many of the worst abuses of alcohol would be prevented if a light wine became the national alcoholic drink of choice instead of whiskey. T.L. Joyce, an Ocoee vintner who was president of the Florida Wine Growers’ Association, wrote in an editorial that it was human nature to want what we are told we cannot have, and so prohibition was doomed to failure. He used his own family as an example—despite his home and workplace being literally stockpiled with wine, he himself generally abstained and made it clear that drunkenness was an intolerable disgrace. As a result, he said, his children and other relatives drank what they wanted but never abused the privilege.

Editorial about prohibition, written by T.L. Joyce, president of the Florida Wine Growers' Association. Joyce enclosed this editorial in a letter to Governor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward in 1908. Click or tap the image to view a zoomable version of the entire letter and editorial.

Yet the counties, like dominoes, continued to fall into the “dry” column. Leon County, including Tallahassee, went dry in 1904, leaving even the highly-respected Emile DuBois unable to market his wines. As a result, DuBois closed up his business and moved to New Jersey, then back to his native France. Many other wineries across the state that had shown so much promise also shut down.

Temperance activists and children ride on a wagon in a parade in Eustis (circa 1919). Some of the signs read "We can't vote, neither can Ma. If Florida stays wet, blame it on-to Pa" and "A saloonless nation 1920."

Most of Florida was already “dry” by local option when federal prohibition went into effect in 1920, which effectively suppressed the winemaking industry. There was still a considerable market for grapes themselves, which kept a number of growers in business, but more challenges lay on the horizon. The arrival of the Mediterranean fruit fly in 1929 was a crushing blow to the industry. As with citrus, grapes were susceptible to infestations of this pest, and shipments of fruit from Florida languished in quarantine when they could not be used locally. To make matters worse, the Great Depression arrived around that same time and suppressed demand for grapes and plenty of other Florida products.

The Florida grape industry, including winemakers, has made a comeback since those days. The number of acres planted in grapes is on the rise, according to the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS), and Florida wineries produced more than 1.6 million gallons of wine in 2016. Moreover, grape growers have access to considerable technical support from IFAS, the Florida Grape Growers’ Association and even a special Center for Viticulture and Small Fruit Research at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee.

Would John Craig, the Tallahassee vintner who waxed poetic about Florida becoming “the Italy of America,” be proud of our state’s viticultural achievements thus far if he could see them? None can say, although we can’t help thinking he would be plenty impressed with Florida’s success in other areas if the wine wasn’t enough to satisfy him. Cheers to that!

Bibliography

Bates, Robert P., et. al. The History of Grapes in Florida and Grape Pioneers. n.p., n.d.

Bennett, Charles Edward. Laudonnière & Fort Caroline : History and Documents. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.

Eagan, Dennis. The Florida Settler, or Immigrant's Guide. Tallahassee: The Floridian, 1873.

Florida Horticultural Society. Proceedings. 1888-1894.

Florida: Its Climate, Soil, and Productions. Jacksonville: Edward M. Cheney, 1869.

Florida State University. Lafayette Anniversary Commencement Program, June 2-5, 1950. Tallahassee: Florida State University, 1950.

Fryman, Mildred L. "Career of a 'Carpetbagger': Malachi Martin in Florida." Florida Historical Quarterly 56, no. 3 (Jan., 1978): 317-338.

Lord, Earl Leslie. Grape Culture in Florida. Tallahassee: Florida Department of Agriculture, 1922.

Paisley, Clifton. From Cotton to Quail: An Agricultural Chronicle of Leon County, Florida, 1860-1967. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1968.

Williams, John Lee. A View of West Florida. Philadelphia: H.S. Tanner, 1827.

Wood, George Alex, Jr. Our French Heritage. Tallahassee: Lewis State Bank, 1970.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Fruit of the Vine: A Brief History of Florida Winemaking in the Late 1800s and Early 1900s." Floridiana, 2021. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/346797.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Fruit of the Vine: A Brief History of Florida Winemaking in the Late 1800s and Early 1900s." Floridiana, 2021, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/346797. Accessed January 8, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2021, October 10). Fruit of the Vine: A Brief History of Florida Winemaking in the Late 1800s and Early 1900s. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/346797

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program