1845 Election Returns

About These Documents

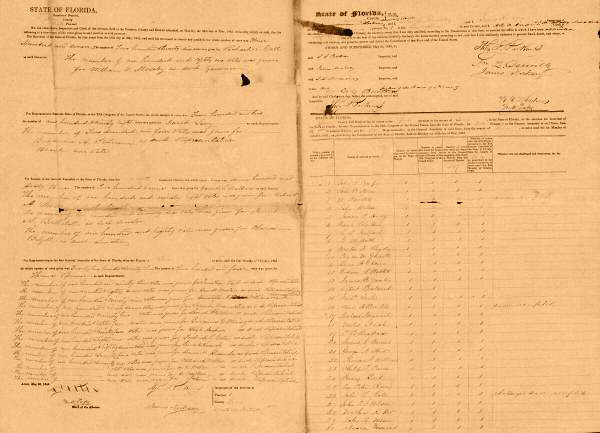

These are returns from the election held on May 26, 1845 to choose a governor, a U.S. Congressman, and state-level representatives for the newly created state of Florida. Florida had attained statehood two months before with the signature of President John Tyler on an act admitting both Florida and Iowa to the Union. Florida’s 25 counties were each divided into voting precincts, each of which submitted a return. Some returns were completely handwritten, but the vast majority used a form supplied by the state government.

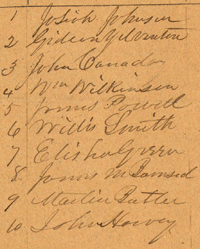

On each return, the county clerk and the election inspectors for the precinct identified the voters’ names, the offices for which they voted, whether their qualifications as a voter were challenged, and what the result of that challenge, if any, was.

The officials also certified the number of votes received by each candidate for each office. It should be noted that the vote totals in many cases do not match the number of votes indicated on the voter list. Also, some precincts included additional documents with their returns, such as muster rolls for militia units.

While these documents are of considerable historical value, they are especially useful for genealogists, as they pinpoint where Florida’s voters were living at the time of the 1845 election. Depending on the circumstances, an ancestor might appear in the 1845 election returns and not in available census records, owing to having moved or died either before or after those censuses were taken.

Background

The United States acquired Florida from Spain following the ratification of the Adams-Onis Treaty in 1821, but for more than two decades it remained a territory rather than a state. In part, this was because Floridians were divided over whether and how Florida ought to enter statehood. As tensions between Northern and Southern states over the expansion of slavery became more prevalent, some pro-slavery Floridians suggested that Florida ought to wait to increase its population so it could enter the Union as two states. This would strengthen the pro-slavery forces in the Senate. Individuals from neighboring states had their own ideas.

Other Florida citizens were eager to get the new territory into the Union as quickly as possible. The editor of Niles’ Weekly Register reported in 1830 that the following toast had been given at a public dinner in support of Florida’s entry: “Florida – as impatient to break into the union, as South Carolina is to break out; perhaps it would be better for both to stay where they are, until better acquainted.” Statehood advocates, such as David Levy (later Yulee) and Robert Raymond Reid, urged the various factions to cooperate so Florida could become part of the Union. As a state, Florida would enjoy the benefits of better representation in Congress, grants of land from the federal government, and national prominence as a place to settle and do business.

When a referendum in May 1838 returned a majority of voters interested in statehood, Governor Richard Keith Call authorized the election of delegates to a constitutional convention at St. Joseph, a port on the Gulf Coast near Apalachicola. The convention began December 3, 1838, and the new constitution was approved on January 11, 1839. Florida voters approved the new document the following May by a narrow margin.

Despite the ostensible approval of the electorate, the Legislative Council did not take immediate action on the Constitution of 1838. The old debate over whether Florida ought to enter the Union as one state or two re-emerged, as did questions over whether Floridians could raise enough tax revenue to support a state government, or whether the narrow vote ratifying the Constitution of 1838 was valid. For several years, it was as though no state constitution had been approved at all.

While the statehood question remained caught in the mire of territorial politics in Florida, voters in Iowa were close to requesting admission to the Union through their representatives. This spurred Florida’s leaders into action. David Levy and other advocates of immediate statehood argued that Florida could not allow Iowa to become a state without Florida joining at the same time. For Iowa to enter without Florida would grant the northern bloc of states an advantage in the U.S. Senate and leave the South vulnerable in future legislative fights over slavery-related policies. Florida’s electorate answered the call by voting into office a pro-statehood Legislative Council. Meanwhile, both houses of Congress approved a bill admitting Iowa and Florida into the Union, and President John Tyler signed it on March 3, 1845. Florida became the 27th state.

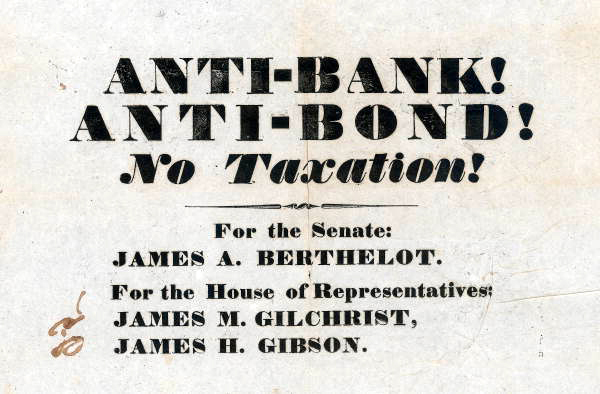

1845 Campaign Broadside promoting

James A. Berthelot for the Senate and

James M. Gilchrist & James H. Gibson for

House of Representaives

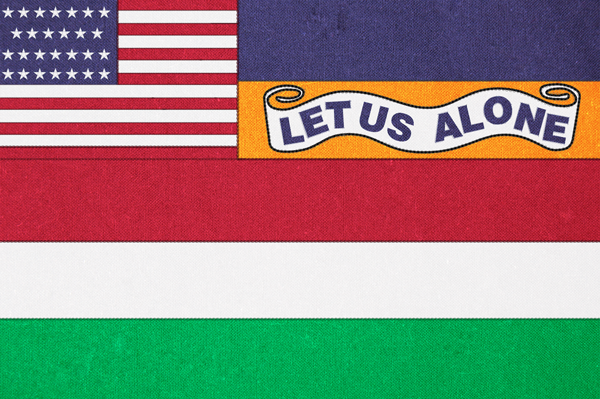

Rendering of the first Florida state Flag

used at the inauguration of William D.

Moseley in 1845.

The debate over statehood was over, but the alteration of Florida’s political landscape was still underway. As a state, Florida needed elections to determine who would represent its people in Congress, who would be the first state governor, and who would fill the newly created state legislature. Territorial Governor John Branch set May 26, 1845 as the date for an election. Local leaders of the Democratic Party held a convention in Madison and nominated Jefferson County planter William D. Moseley for governor, and David Levy Yulee for representative to the 29th U.S. Congress. The Whigs held county-level conventions across the state and selected Richard Keith Call as their candidate for state governor, and Benjamin A. Putnam for Congressional representative. When the votes were tallied, Democrats Moseley and Levy won the day, and their party secured majorities in both houses of the state’s first General Assembly. Governor Moseley was inaugurated on June 25, 1845, with an elaborate ceremony featuring a new, albeit short-lived, state flag for Florida and a gallant display of military salutes. It was official; the State of Florida was a reality at last.

Selected Bibliography

Cash, William T. and Dorothy Dodd. Florida Becomes a State. Tallahassee: Florida Centennial Commission, 1945.

Michaels, Brian E. Florida Voters in their First Statewide Election. Maitland: Florida State Genealogical Society, 1987.

Moussalli, Stephanie D. “Florida’s Frontier Constitution: The Statehood, Banking & Slavery Controversies.” Florida Historical Quarterly 74, no. 4 (Spring 1996): 423-439.

Schafer, Daniel L. “U.S. Territory and State.” In The New History of Florida, edited by Michael Gannon, 207-230. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996.

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program