Florida Memory is administered by the Florida Department of State, Division of Library and Information Services, Bureau of Archives and Records Management. The digitized records on Florida Memory come from the collections of the State Archives of Florida and the special collections of the State Library of Florida.

State Archives of Florida

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- State Archives Online Catalog

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- ArchivesFlorida.com

State Library of Florida

Related Sites

Dust Tracks

The Complete Performances of Zora Neale Hurston from the Florida Folklife Collection

There are few in Florida's cultural history who have had as great an impact as Zora Neale Hurston. Although Hurston is primarily recognized as a novelist, she was also an anthropologist and folklorist. She spent years documenting African-American culture in the South. In the 1930s, she took a job with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) recording African-American folktales and songs in Florida. The 21 tracks on this playlist were recorded while Hurston was employed by the WPA and range from railroad work songs to Bahamian children's songs. These tracks represent the complete recorded performances of Hurston held by the State Archives of Florida.

Early Life

Hurston was born in Notasulga, Alabama, on January 7, 1891, to John and Lucy Hurston.1 The family relocated to Eatonville, Florida, when she was still a toddler. John became a pastor at Zion Hope Baptist Church in Sanford in 1893 while Lucy stayed home to care for and educate the couple’s six sons and two daughters. Growing up in Florida, Hurston was surrounded by the stories her neighbors and family told, as well as the fairy tales she read in books. These amusements also provided a much-needed escape when the Hurston family hit turbulent times. Lucy died in 1904, and John remarried soon after. These events strained Hurston’s relationship with her father, and she thought often of striking out on her own. In her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, Hurston wrote, “The strangest thing about it was that once I found the use of my feet, they took to wandering. I always wanted to go.”2 After her mother’s death, Hurston spent the rest of her life moving from one place to another.

Bottom: Map of Orange County, 1911.

She first went to Jacksonville to attend the Florida Baptist Academy, where her older brother and sister were also enrolled. Hurston spent one year at the school before her father stopped paying her tuition and supporting her financially. At the age of 14, Hurston was left to fend for herself. Among her many jobs was working as a caretaker for her older brother's children in Tennessee. Then in 1917, after spending a year and a half as a travelling maid for the lead singer of a Gilbert and Sullivan repertoire company, Hurston landed in Baltimore, Maryland, determined to finish her education. Hurston lied about her age to attend night classes for free and eventually enrolled in college prep courses at Morgan Academy. In the fall of 1919, she enrolled at Howard University in Washington, D.C., as an English major.

Harlem Renaissance

Hurston’s dream was to become a professional writer. She started out writing poetry but quickly turned to more narrative short stories. She joined the staff of The Stylus, Howard’s annual journal, where she published her poem, “O Night,” and short story, “John Redding Goes to Sea,” in 1921. It was at The Stylus that Hurston met Alain Locke, a philosophy professor and one of the leaders of the Harlem Renaissance (known as the “New Negro Movement” at the time), who had helped found the journal. Locke would be an integral part of her future as an author. Although she was actively writing for Howard publications as a student, she found it difficult to complete some of her coursework. In the spring of 1924, during her last semester at Howard, Hurston didn’t enroll in any courses. She briefly put her education on hold, but she continued to write. After a recommendation from Locke, Hurston was asked to publish in Opportunity, a new magazine launched in New York in early 1923 by the National Urban League. She submitted her short story “Drenched in Light,” and it was published in late 1924—her first nationwide publication. With the possibility of a promising writing career now in front of her, Hurston left Washington, D.C. behind and moved to Harlem in New York City to continue writing and finish her education.

Hurston quickly became acquainted with all of the major players of the Harlem Renaissance, including fellow writer Langston Hughes. She established a reputation for herself as being the life of the party at Harlem soirees and began finding some success as a writer as well. She published more than five pieces in 1925, including her short story, “Spunk,” which Locke included in the seminal anthology The New Negro. After submitting multiple pieces for consideration in the 1925 Opportunity literary contest, she won a prize for “Spunk” and her play “Color Struck.” This recognition resulted in an unexpected offer for Hurston—the chance to enroll at Barnard College. Hurston accepted the offer in September 1925 and completed her degree in 1928, making her Barnard’s first African-American graduate. While enrolled at Barnard, she took anthropology courses at Columbia University, the brother school of Barnard, which would eventually lead her back to Florida.

Under the direction of pioneer anthropologist and Columbia professor Franz Boas, Hurston learned how to conduct fieldwork as an anthropologist. Her anthropology training soon appeared in her writing as she began submitting folktales for publication in addition to fiction. After her spring 1926 semester with Boas, Hurston contributed the folktale “Possum or Pig” to the September issue of Forum and “The Eatonville Anthology” appeared in the September through November issues of Messenger.

She put her skills as a folklorist to the test in February 1927 when she embarked on a solo fieldwork expedition after being awarded a fellowship from the American Folklore Society and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. Among the stops on this trip was Eatonville, Florida, her childhood home. Hurston spent six months traveling mostly around Florida collecting stories, songs and dances from black Southerners. Despite so many months on the job, Hurston considered this trip a failure because she wasn’t able to collect as much unheard material as she had hoped.

It wasn’t long after her return to New York in August that she secured more funding for a second fieldwork expedition, and by December she was on the road again. This second opportunity would prove much more successful and gave Hurston the confidence and experience she needed to establish herself as one of the leading folklorists of black Southern culture. In Florida, she lodged at the Everglades Cypress Lumber Company in Loughman, which put her in a central position to also visit the phosphate mines in Mulberry, Lakeland and Pierce in Polk County. Workers were initially suspicious of the outsider, but Hurston won them over by singing the popular railroad work song “John Henry” and holding competitions with prizes for the person who could tell the best story. Hurston collected children’s songs and games among her material in Florida. The trip wasn’t limited to Florida alone—she also found herself in Alabama, Louisiana and the Bahamas collecting recordings of the origins of hoodoo practices and other material.

After nearly two years working in the field in the South, Hurston returned to New York in March 1930 with plenty of new material. She incorporated some in articles for the Journal of American Folklore in 1930 and 1931, but she was also eager to find a more creative way to share what she had learned. This came in the form of performances in early 1932—“The Great Day,” “From Sun to Sun” and “The Fiery Chariot”—which used songs, dances and other folk traditions she had collected. Her goal, though, was to write a book about black Southern folklore. To escape the bustle of the city and focus on her writing, Hurston returned to Eatonville in April 1932. For the rest of the year she organized the information she had collected, staged performances of “From Sun to Sun” at different Florida venues and continued writing fiction as well. After three months of writing in 1933, Hurston finished the manuscript for Jonah’s Gourd Vine, her first book, and it was published the following year. Her second book, Mules and Men, was published in 1935, and it included folktales she had collected during her fieldwork expeditions in Florida and New Orleans.

Works Progress Administration

Hurston was becoming more known as an author in the 1930s, but she never made enough money from her writings to make ends meet and was constantly looking for ways to support her meager income. So in 1935, she sought employment with the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a relief agency established in 1935 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration to employ thousands of workers affected by the Great Depression. On her first job with the WPA, she joined folklorist Alan Lomax and New York University Professor Mary Elizabeth Barnicle for a collecting trip in Georgia and Florida. Lomax was collecting black folk songs for the Library of Congress, and as a leading expert in black Southern folk culture, Hurston was supposed to help him make contacts to find new material. The three recorded folk songs at St. Simons Island, Georgia, before going to Florida and making stops in Eatonville, Belle Glade, the Everglades and Miami. It was during this trip that Hurston was recorded performing “Bella Mina,” a song about Bahamian rum runners attempting to avoid the authorities by painting their boats black.

in Eatonville, 1935.

Bottom: Gulf, Florida & Alabama Railway

Company turpentine camp.

Hurston then returned to New York and joined the WPA’s Federal Theatre Project, but she only remained in the position for six months. After receiving a Guggenheim fellowship, she spent the next two years conducting fieldwork in the Caribbean. During that time, she published the critically acclaimed novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. When she returned to Florida in early 1938, she was hired by the Florida division of the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) to conduct fieldwork for the program’s “Negro Unit” and scout out locations, such as turpentine camps, churches and juke joints, where other FWP workers could record.

Folklorist Herbert Halpert decided to interview Hurston at the Clara White Mission in Jacksonville in 1939 because of her vast knowledge of folk songs and tales. Carita Doggett Corse, director of the Florida FWP, and fellow folklorist Stetson Kennedy also attended the recording session. In the interview, Hurston discussed how she memorized songs and then performed some of them for Halpert, Corse and Kennedy.

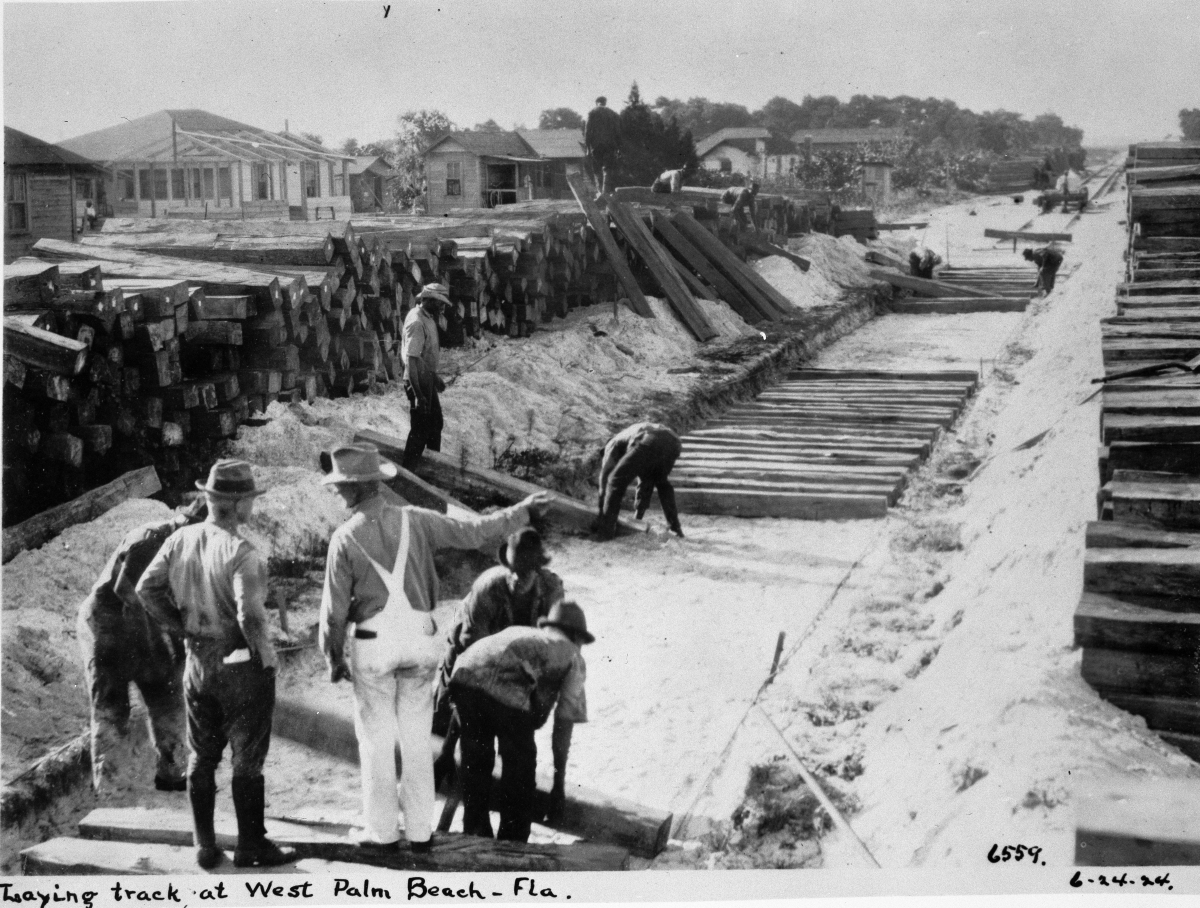

Seaboard Air Line Railway, West Palm Beach,

1924.

Tracks 2 through 7 represent a few of the many railroad songs that Hurston had collected across Florida during the early 1930s. “Gonna See My Long-Haired Babe” and “Dat Old Black Gal” are classic examples of “spiking songs”—songs sung to keep the hammer gang coordinated as they drove railroad spikes into the tracks. Tunes like “Let’s Shake It” and “Shove It Over” were used when the lining crew would come on to move the tracks side to side until the crew captain deemed them straight. She also collected work songs that weren’t specific to railroads, such as “Wake Up, Jacob” and “Mule on the Mount.” The latter tune, Hurston claimed, was the most widely sung work song in America at the time, with countless verses that were still growing and evolving.

Hurston also collected blues and other bawdy social songs, such as “Uncle Bud,” “Ever Been Down” and “Po’ Gal.” She described the first song as a “juke song,” inappropriate to be performed in the company of women. However, Hurston explains that she learned it from women who had spent time in spaces usually reserved for men. “Tampa,” a song sung by children, is similarly meant only for certain ears. Hurston’s ability to collect songs usually reserved for only men or children make her catalog of folk music extensive and diverse.

The final broad category of songs Hurston collected were of Floridians originating from the Bahamas and Sea Islands—barrier islands off the coast of Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. The last three tracks, as well as “Oh, the Buford Boat Done Come” and “Mama Don’t Want No Peas, No Rice,” are examples of music from these places. Many of them are to be sung as accompaniment to dances common in Nassau. “Oh, the Buford Boat Done Come” is meant to accompany a Charleston dance rhythm and was popular among the Gullah people who lived in the Lowcountry region of South Carolina.

Later Career

In August 1939, Hurston left her job at the WPA and moved to Durham, North Carolina, to teach at the North Carolina College for Negroes. She left her position at the college in early 1940 and went on a collecting expedition with anthropologists Jane Belo and Margaret Mead. The three recorded the religious trances, stories and music of the Gullah people in Beaufort, South Carolina. After moving to California in 1941, Hurston completed her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, which was published in 1942. She spent the remaining years of the decade moving between Florida and New York, taking temporary jobs with political campaigns and continuing to write. Her last published book, Seraph on the Suwanee, was released in 1948.

Hurston spent the early 1950s publishing in the Pittsburgh Courier about the trial of Ruby McCollum taking place in Suwannee County, Florida. As her health declined in the latter half of the decade, Hurston was unable to continue writing. After a stroke in late 1959, Hurston moved to the Lincoln Park Nursing Home in Fort Pierce, Florida. She died on January 28, 1960.

See the Zora Neale Hurston Digital Archive from the University of Central Florida for a bibliography of her writing.

Download the playlist as a ZIP file containing 320kBps MP3s.

1. Bella Mina

Recorded June 1935 by Alan Lomax, Zora Neale Hurston, and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle in Chosen

(S1576, T86-237)

2. Gonna See My Long-Haired Babe

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-243)

3. Let's Shake It

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-243)

4. Dat Old Black Gal

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-243)

5. Shove It Over

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-243)

6. Mule on the Mount

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

7. Let the Deal Go Down

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

8. Introduction to "Uncle Bud"

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

9. Uncle Bud

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

10. Oh, the Buford Boat Done Come

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

11. Ever Been Down?

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

12. Halimuhfack

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

13. "How do you learn most of your songs?"

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

14. Tampa

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

15. Po' Gal

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

16. Mama Don't Want No Peas, No Rice

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

17. Crow Dance

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-244)

18. Wake Up, Jacob

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-245)

19. Oh, Mr. Brown

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-245)

20. Tilly, Lend Me Your Pigeon

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-245)

21. Evaline

Recorded June 1939 by Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-245)

Features

Territorial Legislative Council Records, 1822-1845

Documenting Florida's legislature prior to statehood

State and County Officer Directories, 1868-1969

Lists of Florida's state and county officials either elected or appointed between 1868 and 1969.

Guide to Military Records and the Wartime Experience

A guide to government records and manuscript collections relating to service members and the wartime experience.

Dust Tracks

21 tracks from Hurston's time documenting African American culture for the WPA in 1930s Florida.

History Day 2025

Resources for Florida History Day from the State Library and Archives of Florida.

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program