Florida Memory is administered by the Florida Department of State, Division of Library and Information Services, Bureau of Archives and Records Management. The digitized records on Florida Memory come from the collections of the State Archives of Florida and the special collections of the State Library of Florida.

State Archives of Florida

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- State Archives Online Catalog

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- ArchivesFlorida.com

State Library of Florida

Related Sites

Alma, Corazón y Vida

Latin American Music from the Florida Folklife Collection

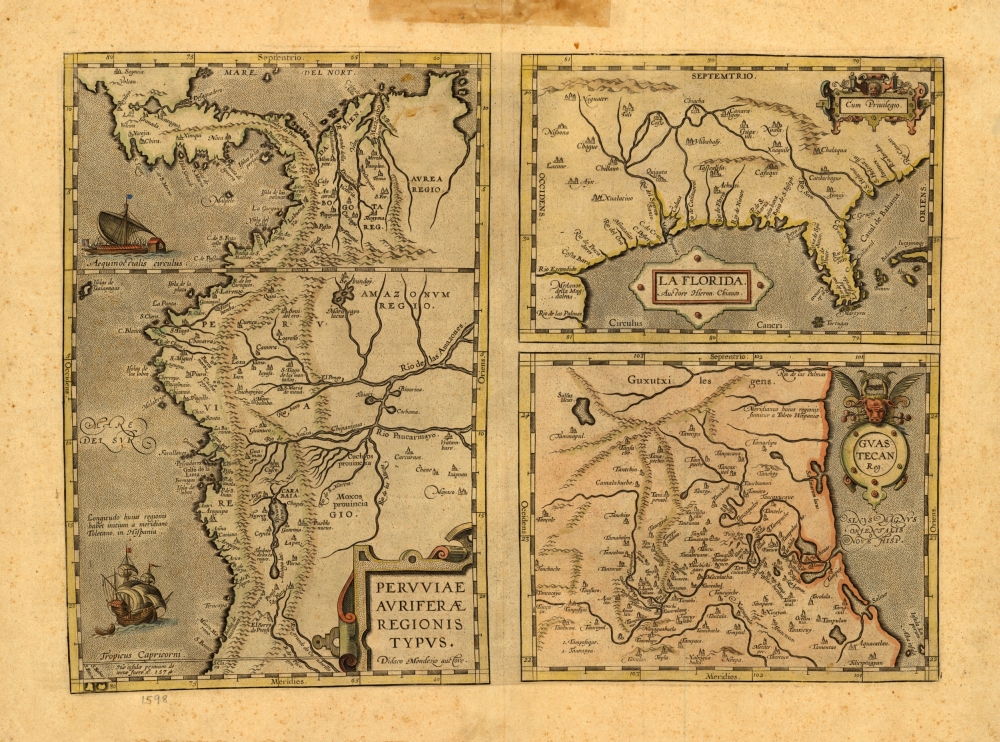

From the salsa of the Caribbean and samba of Brazil to the huayno of the Andes and corridos of Mexico, the distinct and diverse musical traditions of Latin America have had a significant and continuous impact on Florida for centuries. Almost one out of every four Floridians trace their roots back to these Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries that lie south of the United States,1 resulting in an abundance of Latin American musical traditions throughout the state. The 20 tracks compiled here represent only a small sample of the Latin American music in the Florida Folklife Collection at the State Archives. As the Florida Folklife Program continues its efforts to document these musical forms as they change, the State Archives preserves their work so future generations can listen to and explore Latin American musical traditions across the state.

Caribbean Latin America

No region of Latin America has influenced Florida’s culture more than the Greater Antilles in the Caribbean. With over two million Floridians claiming Cuban, Dominican or Puerto Rican ancestry,2 this outsized influence should come as no surprise. The Spanish made first contact with the Americas on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola in 1492, meeting the Taino natives and beginning a long and fraught history of cross-cultural exchange between Europeans and indigenous people. In addition to Taino and Spanish influences, Caribbean Latin America was also shaped by the hundreds of thousands of African slaves brought over to work on the sugar plantations. The music and cultures of these three disparate groups blended over centuries to produce a diversity of genres, styles and traditions.

Some of the earliest musical innovations found in Caribbean Latin America resulted from the mixture of African religious traditions with the Catholicism of Spain. Religions such as Santería blended the highly interactive call-and-response singing and densely interlocking rhythms of West African ceremonial music with the Catholic Church’s veneration of saints. For example, “Obatalá,” the father of all orishas (or spirits) in the Yoruba religion of West Africa, is combined with Our Lady of Mercy, another title for the Virgin Mary. On the third track, Batá drummer Ezequiel Torres and vocalist Olympia Alfaro demonstrate eggüado, the specific rhythm used to summon Obatalá to take possession of worshippers in a Santería ceremony.

“Obatalá” and the other tracks that make up the first 10 of the playlist represent the diversity and intermixing of genres and styles originating in Caribbean Latin America. Many of them are based in the traditional Cuban genres of son, rumba, canción, danzón and punto guajiro.3 However, these genres may be better understood as interconnected subgenres determined by style, instrumentation and the makeup of traditional ensembles. Perhaps none better illustrates this than son, which grew out of mixing Spanish plucked instruments with African-derived percussion in the 18th century. As it flourished into Cuba’s most important musical genre, it developed and expanded from the rural dance music of eastern Cuba to the bedrock of much of the music of Caribbean Latin America.

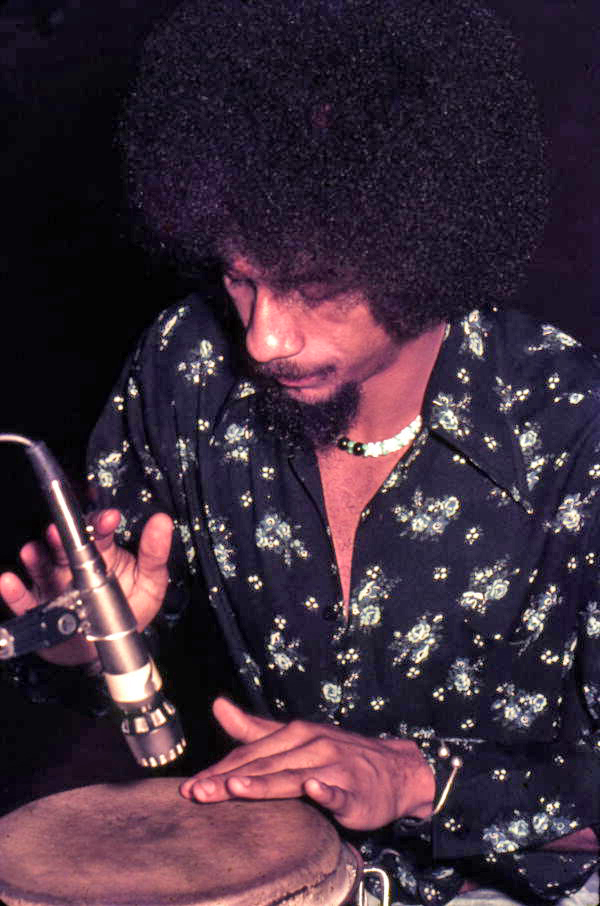

One stylistic offspring of son that best demonstrates its development and influence throughout Latin America is salsa, a fully internationalized genre no longer associated with any single country. “Vive y Vacila,” performed here in 1981 by Adalberto Santiago and Salsa Express, is illustrative of how cosmopolitan the genre is. The song was originally recorded in 1969 by salsa pioneer Ray Barretto, a New Yorker of Puerto Rican ancestry who was deeply influenced by Cuban son montuno. Even the name “salsa” is international in its origin, as Salsa Express’s conga player Raul Menendez explains in an interview with folklorists Peggy Bulger and Doris Dyen:

What is funny is that the real name of the music is not “salsa.” “Salsa” was the name that was given to it by a Venezuelan disc jockey—but the name of it is “guaracha” or “son montuno.” It’s different types of music. But just to name it under one name, we speak of “salsa.” […] They have many different names, but they’re all poured into one name.

“Vive y Vacila” is, more specifically, a salsa dura – a subgenre characterized by intense percussiveness and an emphasis on the musicality of the instrumentalists. Lead singer Adalberto Santiago was in fact the vocalist on Barretto’s original recording, as well as an important originator of salsa dura in his own right as a member of the Fania All-Stars during the 1960s. At the song’s zenith, as he urges the soloists on during the improvised vamp section known as the montuno, Salsa Express can be heard responding “vive y vacila” (“live and enjoy yourself”) – a timely sentiment for many of the 125,000 Cuban refugees who arrived in Florida during the Mariel boatlift the year before.

Tracks seven through nine are also deeply based in son, but, like salsa music, they too have been influenced by a number of other styles. When pianist Facundo Rivero combined Santería with son on his 1954 recording of “Eleguá (El Niño de Atocha),” it was closer to the traditional roots of the genre. But by the time of the performance featured here at Club Bosque in Miami 30 years later, the song exhibits the influence of innovations in Latin American music over that time. Similarly, one-man band Renesito Avich demonstrates the ongoing development of son in his use of live looping and pre-recorded samples in “Yo Canto en el Llano,” a popular song originally composed and recorded in 1953 by the well-known trova duo, Los Compadres. Avich, Los Compadres, and hundreds of other performers as diverse as Pete Seeger and Julio Iglesias have performed “Guantanamera,” arguably the most iconic Cuban song ever written. The composition is also a fine example of guajira-son, a subgenre featuring the rustic lyrical imagery and stylistic mannerisms reminiscent of the guitar music popular among rural Cubans at the turn of the 20th century.

c. 1976

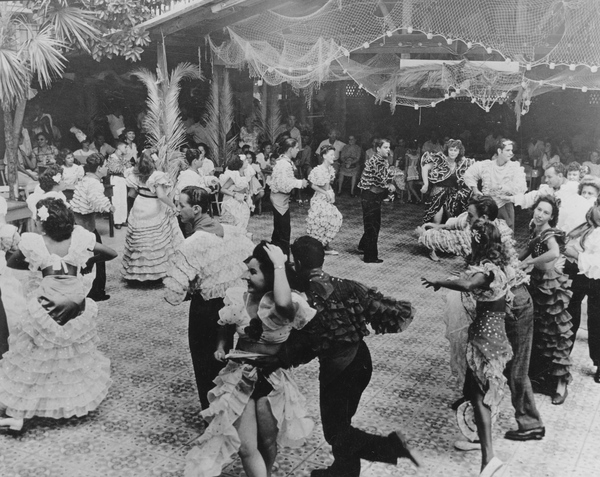

Bottom: Conga line during carnival in

Key West, 1949

Another important genre in Caribbean Latin American music is rumba, a complex of subgenres characterized by the African-derived barrel-shaped drums called congas. Los Rumberos Unidos’ rendition of “Agua Que Va Caer,” composed and originally recorded in 1968 by rumba legends Carlos “Patato” Valdez and Eugenio “Totico” Arango, exemplifies the most distinctive features of guaguancó, the quintessential rumba subgenre. It follows a typical rumba structure: The lead singer introduces the theme of the song during an introductory section called the diana, after which the rumba begins. The clave, a repeated five-stroke rhythm, then guides the battery of conga drummers through the verse section (known as the canto) and into the call-and-response of the montuno.

Developing closely with rumba in urban Cuba during the late 19th century, comparsas also feature an array of drums centered around the conga. Comparsa ensembles, though, required mobile instrumentation in order to accompany parading dancers. Listening to Cayo Hueso Comparsa’s performance on “Skin Salad (Ensalada de Cuero),” one can easily imagine revelers in African-derived attire displaying banners and waving flags as they march through the streets during carnivals.

Like son, rumba found its way into a variety of Latin American styles outside of Cuba. For example, Santería, rumba and jazz were brought together in 1947 by Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo and bebop trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie on their classic tune, “Manteca.” Performed here by the Miami Latin Jazz Ensemble at the 1996 Florida Folk Festival, the composition’s combination of Cuban rhythms with the virtuosity and improvisational complexity of American jazz is the epitome of Afro-Cuban jazz. In transcultural collaborations like these, we can see how Caribbean Latin American music has changed since it was exported to Florida and other non-Spanish speaking regions in North America hundreds of years ago.

The popularity of Cuban son and rumba had a deep impact on other Caribbean Latin American musical traditions, especially the Afro-Puerto Rican drum and dance genre known as bomba, the characteristic rhythms of which are demonstrated on Track 6. During the 18th century, bomba served as a means of socialization and expression for slaves and free blacks in Puerto Rico, but the migration of Caribbean slaves seeking freedom in Puerto Rico brought deep changes to the music during that time. The rhythms of bomba were further altered by the rise in popularity of salsa and guaguancó in the 1960s, leading many groups to mix those genres with bomba, evolving the music even more. However, traditional groups like Ballet Folklórico de Bomba y Plena Lanzó continue to perform less adulterated interpretations of bomba such as “Yo Llegaré.”

South America

There are almost three-quarters of a million people of South American ancestry in Florida – more than any other state in the United States.4 The diverse Iberian, African and indigenous musical heritages that combined and developed over hundreds of years in South America have found a fertile home in Florida. Tracks 11 through 15 of this playlist give a sample of some of those different regional sounds and styles.

Six years after arriving in Hispaniola, the Spanish made landfall on the coast of Venezuela. As in the Caribbean, the music of Venezuela traces its roots back to indigenous, African and European influences. The folk music which has developed since the arrival of Europeans and Africans is called criolla – a reference to creoles, the rural folk of mixed ancestry who created the tradition. One of the most iconic instruments in this tradition, and an important symbol of Venezuelan music generally, is the arpa llanera, a 34-stringed harp descended from the diatonic harps of 17th-century Spain. Known as the “plains harp” in English, it is the main purveyor of Venezuela’s quintessential folk dance music: joropo. The sophisticated and somewhat complex rhythm and structure of a joropo can be heard on tracks 12 and 15. On the former, Jesús Rodríguez demonstrates a “Pasaje” – a joropo section characterized by more melodic freedom and a slower pace. The brisker “Embrujo” exhibits the impressive rhythmic and melodic virtuosity of the contrasting golpe sections.

While indigenous influences are somewhat muted in Venezuelan criolla, the musical heritage of the native Quechua and Aymara people in the Andes has become emblematic in Peru. At the turn of the 20th century, composer Daniel Alomía Robles journeyed through the Andes in search of indigenous folk music untouched by Iberian or African influence. The result was an upbeat composition inspired by the popular Quechua song-dance genre huayno for his 1913 operetta called “El Cóndor Pasa.” The tune, performed here by Inca Spirit, became an icon of Peru’s national cultural heritage and was famously covered by the pop duo Simon & Garfunkel in 1970, whose recording featured the Andean siku (panpipe), quena (flute) and a small guitar called a charango.

Peru also has a folk music tradition exhibiting African, European and indigenous influences comparable to Venezuelan criolla. The complex of subgenres that make up Peruvian música criolla is best represented by the vals criollo, an adaptation of the mid-18th century Viennese waltz. Developing among the urban working class in the barrios of Lima, the Peruvian waltz became the country’s foremost national music form during the 1920s and 1930s. By the time Adrián Flores Albán composed “Alma, Corazón y Vida” in 1949, vals criollo was gaining international popularity throughout Latin America. Albán’s soaring tribute to “soul, heart and life” has since become a classic and found its way into the repertoires of non-Peruvian ensembles such as Grupo Cañaveral, a pan-American band with members from Cuba, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Like Grupo Cañaveral, Johnny Conga’s ensemble, Roots of Rhythm, is meant to promote and educate listeners about Latin American musical traditions. On “Afro-Samba,” Conga demonstrates his Afro-Cuban interpretation of samba, Brazil’s best-known and most important musical form. As with Cuban son, samba is a network of popular styles which share rhythmic elements that can be traced back to Africa. In the case of samba, these origins are thought to be the Bantu musical traditions of sub-Saharan Africa. While its origins and development are a source of some scholarly disagreement, all concur that samba’s most iconic association is with the processions in the Carnaval of Rio de Janeiro. While Roots of Rhythm lacks some of the characteristic instrumentation of the samba percussion ensembles known as baterias, they are still able to capture the polyrhythmic intensity of a parading samba band.

Northern Latin America

The countries that make up northern Latin America contain hundreds of musical strands and marked cultural variation between them. Before the Spanish made first contact on the Yucatán Peninsula around 1502, the region was controlled by the Aztec and Maya – two deeply musical civilizations. As the newcomers established colonies in the 16th century, musical acculturation developed alongside a growing mestizo culture, drawing on both native and Spanish influences. While Mexico and many countries in Central America are populated mostly by Spanish-speaking mestizos, Guatemala is the only country that can claim a significant population with full Mayan ancestry. Despite this distinction, the borders dividing Mesoamerican and mestizo music in Guatemala and other countries in northern Latin America are obscured by an extensive overlapping of cultures.

A perfect example of how these lines are blurred can be seen on “Guadalajara,” a popular Mexican ranchera originally intended to be performed by mariachi ensembles. But Marimba Mayalandia’s version on track 15 transposes the tune onto the marimba, a type of large wooden xylophone played by up to four musicians. While the marimba’s origins are most likely in central Africa, since the 17th century it’s become a fixture in the Mayan musical tradition and Guatemala’s most popular folk-derived instrument. As with many tracks on this playlist, “Guadalajara” embodies the diverse ways that indigenous, African and European cultures combine in Latin America.

Festival in White Springs, 1957

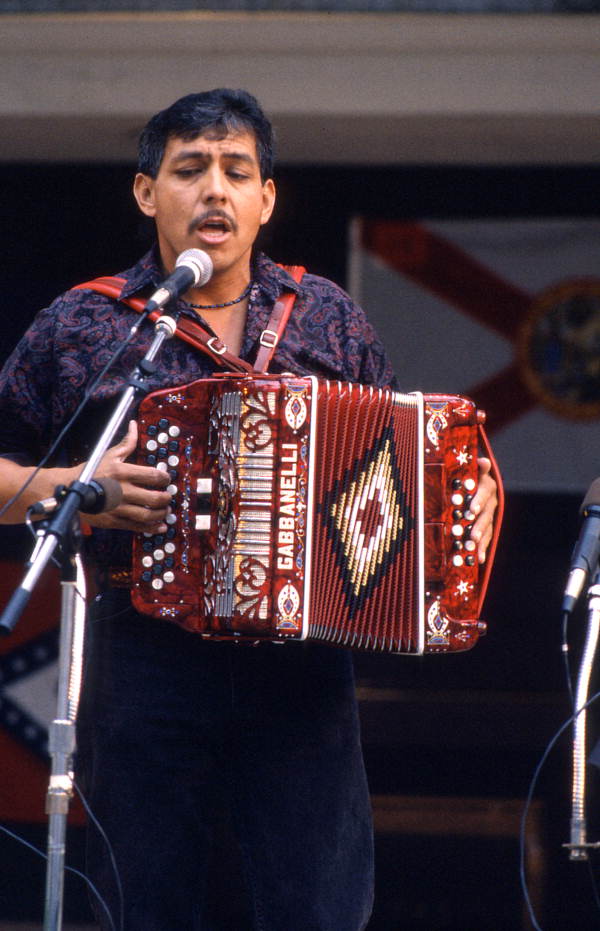

Bottom: Accordionist Tomás Granado at

the Florida Folk Festival in White Springs, 1992

Of the more than one million Floridians who claim descent from the countries of northern Latin America, over half identify as having Mexican ancestry.5 The last five tracks on the playlist represent the impact of folk-derived Mexican styles on Florida’s music culture. Mariachi, jarocho and other kinds of música típica that developed in Mexico during the 19th century expanded into the international market during the 1930s. Popular songs such as “Cielito Lindo” gained international fame during that time through their use in films as a way to evoke romanticized depictions of Mexican rural life. These ranchera cowboy songs, with themes of passion, treachery and adventure, became the foundation of Mexico’s most prominent folk-derived musical ensemble, the mariachi.

“Tomando Licores” is a ranchera in the norteño style of northern Mexico. German polka and traditional ballads formed the initial foundation of música norteña, but since its rise in the 1950s, styles and songforms from across Latin America have found their way into the repertoires of norteño ensembles. These ensembles, known as conjuntos, perform a range of folk-derived Mexican music, including ranchera, huapango and their own version of cumbia, a Colombian rhythm and dance form from the Caribbean coast. On track 16, accordion virtuoso Tomás Granado’s group Mestengo performs the cumbia norteña, “Una Morenita.”

One of the foundational songforms in música norteña is the corrido, a long narrative ballad akin to the Spanish romance. During the Mexican Revolution, the corrido became widely popular due to its ability to portray socially relevant news and events, as well as subvert propaganda being spread by the government. The songs were melodically simple and sung in an unburdened manner that accentuated the lyrics. A century later, the corrido continues to recount current events, but it also serves as a vehicle for expressing romantic affection, as in the Galarza Brothers’ rendition of “Vuela Paloma.”

The various Latin American styles represented on this playlist share deep roots in indigenous, African and European musical traditions, yet retain their own unique features. As the Latin American population in Florida grows larger every year, these traditions will inevitably continue to diversify and evolve, enriching our state’s cultural heritage with ever newer and more original innovations in dance, music and folklife.

1 "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Florida," accessed July 12, 2018, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/fl/PST045217.

2 "Ancestry in Florida (State),” accessed July 12, 2018, https://statisticalatlas.com/state/Florida/Ancestry#figure/hispanic-ancestry.

3 Information about traditional Latin American music in these liner notes comes largely from Dale A. Olsen and Daniel E. Sheehy, eds., The Garland Handbook of Latin American Music (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 2000). Please refer to this expansive work for further detailed information about genres and styles mentioned in the text.

4 "Ancestry in Florida (State)."

5 Ibid.

Download the playlist as a ZIP file containing 320kBps MP3s.

1. Vive y Vacila – Adalberto Santiago & Salsa Express

Recorded August 14, 1981, by Peggy Bulger & Doris Dyen in Miami

(S1576, T81-67)

2. Agua Que Va Caer – El Gran Meñique & Los Rumberos Unidos

Recorded May 27, 1995, by Signi Evans & Roger Shields in White Springs

(S1576, D95-42b)

3. Obatalá (Eggüado) – Ezequiel Torres with Olympia Alfaro

Recorded May 27, 2000, by Rita Jane Iacino in White Springs

(S1576, C00-80)

4. Manteca – Miami Latin Jazz Ensemble

Recorded May 26, 1996, by Jim Lassiter in White Springs

(S1576, D96-19c)

5. Skin Salad (Ensalada de Cuero) – Danny Acosta & Cayo Hueso Comparsa

Recorded May 24, 1991, by Julie Langevin in White Springs

(S1576, T91-15a)

6. Bomba Demonstration – Plena Es

Recorded May 28, 2017, in White Springs

(S2034, fls-3_270)

7. Eleguá (El Niño de Atocha) – Ilusión 60 with Facundo Rivero & La India de Oriente

Recorded August 12, 1985, by Laurie Sommers in Miami

(S1576, T86-73)

8. Guantanamera – Grupo Cañaveral

Recorded May 23, 1986, in White Springs

(S1576, T86-29)

9. Yo Canto en el Llano – Renesito Avich

Recorded May 26, 2017, in White Springs

(S2034, amp-1_531)

10. Yo Llegaré – Ballet Folklórico de Bomba y Plena Lanzó

Recorded May 30, 2004, in White Springs

(S2034, CD04-113)

11. Afro-Samba – Johnny Conga & Roots of Rhythm

Recorded May 26, 1996, by Beth Videon in White Springs

(S1576, D96-18d)

12. Pasaje – Jesús Rodríguez

Recorded June 17, 1991, by Bob Stone in Naples

(S1640, Tape 25)

13. Alma, Corazón y Vida – Grupo Cañaveral

Recorded May 24, 1991, by Julie Langevin in White Springs

(S1576, T91-17b)

14. El Cóndor Pasa – Inca Spirit

Recorded May 26, 2000, by Janet Stainer in White Springs

(S1576, D00-7c)

15. Embrujo – José Palmi

Recorded June 27, 1993, by Bob Stone in Miami

(S1640, Tape 22)

16. Guadalajara – Rafael Rivera & Marimba Mayalandia

Recorded May 18, 1996, by Bob Stone in Orlando

(S2029, C01)

17. Una Morenita – Mestengo

Recorded November 10, 2007, in White Springs

(S2034, CD07-38)

18. Vuela Paloma – The Galarza Brothers

Recorded May 25, 1985, in White Springs

(S1576, T85-117a)

19. Tomando Licores – Los Halcones de Michoacán

Recorded November 13, 1994, in by Bob Stone in Homestead

(S2029, C01)

20. Cielito Lindo – Mariachi Jalisco

Recorded September 4, 1985, by Nancy Nusz & Laurie Sommers in Homestead

(S1576, T86-78)

Features

Territorial Legislative Council Records, 1822-1845

Documenting Florida's legislature prior to statehood

State and County Officer Directories, 1868-1969

Lists of Florida's state and county officials either elected or appointed between 1868 and 1969.

Guide to Military Records and the Wartime Experience

A guide to government records and manuscript collections relating to service members and the wartime experience.

Dust Tracks

21 tracks from Hurston's time documenting African American culture for the WPA in 1930s Florida.

History Day 2025

Resources for Florida History Day from the State Library and Archives of Florida.

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program