Florida Memory is administered by the Florida Department of State, Division of Library and Information Services, Bureau of Archives and Records Management. The digitized records on Florida Memory come from the collections of the State Archives of Florida and the special collections of the State Library of Florida.

State Archives of Florida

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- State Archives Online Catalog

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- ArchivesFlorida.com

State Library of Florida

Related Sites

Bound to Ride

Train Songs from the Florida Folklife Collection

The rise of railroads in the United States during the 19th century inspired a new folk music tradition with the iron horse as its theme. Work songs, hobo stories, train wreck ballads and other railroad songs are found in folk music all over the United States, and are especially numerous in Florida — you can still hear songs about trains each year at the Florida Folk Festival in White Springs. This selection of 22 tracks from the Florida Folklife Collection at the State Archives, where railroad songs are abundant, spans nearly 70 years and represents only a sampling of the material available about railroads in the archives.

The Rise of the Railroads

Soon after Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, the first steam-powered locomotive to run on a track was developed in New England. North Florida plantation owners and entrepreneurs were eager to use this new technology to expedite the movement of cotton and other crops to Gulf ports for shipment to the textile mills in New England and Europe.

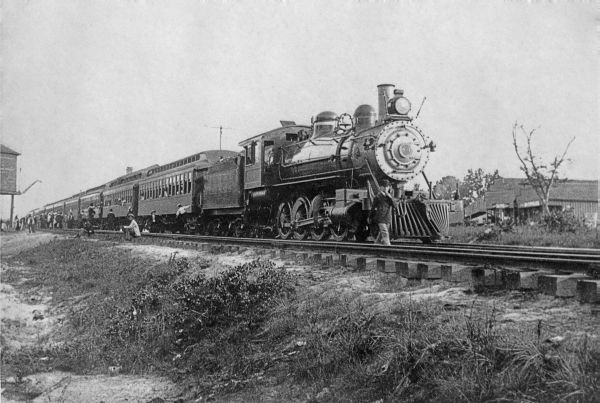

The first railway line to operate in the state was the Lake Wimico line, which ran Florida's first steam-powered engine from the booming port town of St. Joseph to the Apalachicola River beginning in 1836. One year later, the Tallahassee Railroad Company relied on both enslaved and free black laborers to complete the 22-mile Tallahassee-St. Marks line, a rudimentary, mule-powered train that followed wooden tracks from the territorial capital to the southern terminus of St. Marks.

When Florida was admitted to the Union in 1845, the country was experiencing a railroad boom. Eager to stake Florida's place in the rising industry, officials advocated for further development of railroad infrastructure to connect commerce hubs across the state. Railroad investors made slow yet steady progress in the years leading up to the American Civil War, but wartime destruction devastated Florida's nascent railroad network. By war's end, nearly every railway investment company in the state had defaulted on their bonds, sinking Florida into massive debt during Reconstruction.

Florida experienced a railroad revival in the 1880s when Pennsylvania real estate developer Hamilton Disston purchased four million acres of state land. With that investment, Florida was back in the black and ready to develop new transportation infrastructure. Railroad magnate William Chipley convinced one of the largest regional rail lines, Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N), to take over the floundering Pensacola Railroad, resulting in the development of new communities like Crestview, DeFuniak and Chipley along the Panhandle line. Transportation tycoon Henry Plant's Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and others like it connected Floridians with destinations all over the state.

One of Plant's competitors, Henry Flagler, financed the Florida East Coast Railway. Flagler's eastern line is often credited with transforming Dade County from an underdeveloped area of just 257 residents in the 1890s into a booming metropolis decades later. According to Florida folklore, Julia Tuttle, a wealthy Miami landowner, sent orange blossoms grown in the remote southern city's tropical winter to persuade Flagler to extend his eastern rail there, which he did in 1896. By 1912, the Florida East Coast Railway was carrying goods and passengers from Jacksonville to Key West.

Work Songs & Folk Ballads

Without hardworking laborers, Florida's railroads would not have succeeded. Building and maintaining the rails in Florida's hot, humid, mosquito-ridden, hurricane-prone environment required intense physical labor. Southern blacks and whites seeking gainful employment often took jobs in segregated section gangs, but some companies preferred to recruit out-of-state laborers, many of whom were veterans or immigrants of Italian, Irish, Greek, Minorcan, Central American and Caribbean origin.

Section gangs tasked with maintaining the tracks were known colloquially as "gandy dancers." The name is of uncertain origin, but many researchers claim it was derived from both the motion used to shove the track over as well as the manufacturer of the tools used on the job — the Gandy Shovel Company. These workers used track-lining songs to help coordinate the various aspects of rail construction and maintenance. An actual instance of lining track can be heard in full effect on Track 3, a 1958 field recording of a racially-integrated section gang on the Southern Railway outside of White Springs. Here, the workers follow the directions of the "caller," who indicates which direction and how much to shift the track.

On "Let's Shake It," folklorist Zora Neale Hurston describes and demonstrates how gandy dancers like Bradley Eberhard, performer on Track 4, would coordinate their work with music on railways throughout Florida. A track-lining demonstration can also be found on Track 9, which features a group of retired gandy dancers, including NEA National Heritage Fellowship recipients John Henry Mealing and Cornelius Wright Jr.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Florida's prison bureau regularly leased out convict laborers to assist with the backbreaking railroad work. A crew from the State Prison Farm in Raiford was recorded performing the iconic work song "Take This Hammer" by folklorists John & Ruby Lomax during their 1939 recording expedition for the Works Progress Administration's (WPA) Federal Writers' Project. The lyrics are the result of informal rearrangements of countless floating verses from a shared oral tradition, resulting in regional variations throughout the country.

Train ballads and folk songs were written about both engineers and railway workers, often highlighting the dangers of working on the lines. As traffic and speeds increased, passenger and worker safety became a concern. Train derailments left a tragic mark on rail history, with tight turns, faulty brake systems and pressure to keep the trains running on time causing fatal accidents from Jupiter to Lloyd.

Many enduring railroad ballads focusing on the train's engineer emerged out of these tragedies. "The Ballad of Casey Jones" is about the title character's valiant effort to save the lives of his passengers in a fatal collision in 1900. "Wreck of the Old 97" tells the story of a train derailment in 1903 along the Southern Railway due to excessive speeds. Not all ballads, though, end in sorrow. "Bill Mason" and the night express were saved from careening off the end of a bridge under construction when his new bride flagged him down in the nick of time.

Bottom: Convict-lease workers in Volusia County, 1914

Train ballads about railway workers did more than draw attention to the tragedies of working on the rail lines; they told stories about railroad heroes and villains. Railway worker and African-American folk legend John Henry lends his name to an iconic railroad ballad. Arguably the most widely performed and famous of all railroad songs, "John Henry" is the archetypal man against machine narrative that recounts Henry's death in a Pyrrhic victory over the newly invented steam drill. The story has many variations, but Bill McLaughlin's version for the WPA, learned during his childhood from an African-American cook in Jacksonville, contains many of the most common tropes. Echoes of the story can also be heard in the aforementioned work song, "Take This Hammer," specifically in the line "Must be the hammer that killed John Henry, but it won't kill me."

The legend of "Railroad Bill" tells the story of a convict-lease worker turned notorious outlaw from northern Florida. In 1895, Railroad Bill opened fire after he was found sleeping on a water tank along the L&N Railroad in southern Alabama and gained a reputation in African-American folk culture as a "badman" after he killed a sheriff during the ensuing manhunt. He took to robbing trains and allegedly giving the goods to poor African-Americans along the train line, which made him a hero in the eyes of many railway workers. The L&N put up a massive bounty for his capture, and after many misidentified African-Americans were killed in attempts to apprehend him, he was eventually gunned down in 1896. While Etta Baker's impressive instrumental version lacks the lyrical narrative, it retains the symbolism of the racial and economic divide in Jim Crow Florida.

"Railroad Bill," "John Henry" and "Midnight Special" were all popular songs among black convict-lease prisoners in the early 1900s because they contained messages of resistance and hope. Many of these songs would lay the foundation for the country blues music of the 1920s and 1930s.

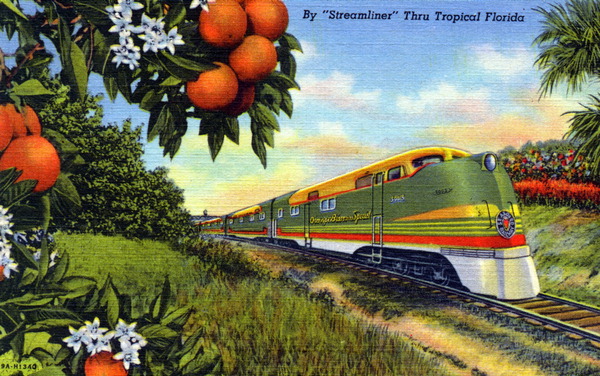

The Golden Age & Decline

By the 1920s, the nation had entered a golden age of train travel. In the midst of a huge land boom, railroads fueled Florida's rapid development. The famed Orange Blossom Special and the Florida Special brought tourists and new permanent residents into the state, while commercial lines were used to transport the state's abundance of agricultural products.

It was during this time that country blues musicians Richard Williams, William "Washboard Bill" Cooke, Reverend Dan Smith and Moses "Doorman" Williams came of age and began their musical careers. They relay their personal encounters with the railroads running through the state in the songs they perform. "Old Forty," for instance, is about a passenger train on the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad that ran through Richard Williams' native Alachua County.

Washboard Bill, an experienced Florida rail worker who spent much of his time hoboing from one job to the next, sang about the familiar sights and sounds of the tracks. On "Hobo Story," he talks about his life as a hobo during the Great Depression.

The sounds of trains became so iconic that many musicians, including bluesmen Dan Smith and Moses Williams, sought to imitate the chugs and whistles verbatim, as exemplified on Tracks 8 and 11. Robert Dixon's performance of "The Brakeman's Blues," a 1928 composition by country pioneer and prolific railroad song composer Jimmie Rodgers, features some of Rodgers' more impressionistic imitations of train whistles, known as "blue yodels."

With the rise of automobiles and airplanes in the 1930s and 1940s, railroads steadily declined. During this decline, old-time music developed into bluegrass, a new musical genre that integrated much of the railroad imagery from train ballads, folk songs and country blues. Old-time barn burners like "Lost Train Blues," recorded at the State Prison Farm on the same WPA trip that produced "Take This Hammer," were the forebears of bluegrass hits like the Stanley Brothers' "Bound to Ride," covered here by Frank Lindamood.

Despite the American railroad's decline, folk musicians continued writing new songs about trains. In 1938, fiddler Ervin T. Rouse immortalized Florida's signature passenger train, the Orange Blossom Special. Performed here in two versions, one by folk troubadour and Florida icon Gamble Rogers and another by fiddle virtuoso Donald "Chubby" Anthony, "Orange Blossom Special" quickly became a bluegrass hit. Many American musicians, including the "Father of Bluegrass Music" himself, Bill Monroe, covered what came to be known as "the fiddle player's national anthem."

The creation of the Interstate Highway System in the 1950s further altered the role of railroads in the American economy as passengers throughout the country sought faster modes of transportation. Towns that had developed around Florida's railway stops languished in the shadows of the new highways and the effects were reflected in folk songs. Folk balladeer and Florida Folk Heritage Award recipient Don Grooms illustrates this phenomenon in his composition "The Orange Blossom Special Don't Stop in Waldo Anymore."

Even though railroads as transportation became less and less important through the latter half of the 20th century, railroad nostalgia inspired singer-songwriters to harken back to the "good old days" of steam-engines and train whistles. Songs such as Norman Blake's "The Weathered Old Caboose Behind the Train" serve as testaments to the great railway lines of the early 1900s.

Although the names of engines and railroads become more distant and unfamiliar as the years go by, the songs that were sung along their tracks continue to resonate in the American music vernacular. The legacy of Florida's railroads remains foundational to the state's diverse folk music traditions.

Download the playlist as a ZIP file containing 320kBps MP3s.

1. Take This Hammer – Raiford Penitentiary Inmates

Recorded June 4, 1939, by John & Ruby Lomax in Raiford

(S1576, T86-243)

2. Let's Shake It – Zora Neale Hurston

Recorded June 18, 1939, by Stetson Kennedy & Herbert Halpert in Jacksonville

(S1576, T83-243)

3. Track-Lining Song – Southern Railway Extra Gang No. 4

Recorded in 1958 by Thelma Boltin near White Springs

(S1576, T86-227b)

4. L&N Mobile – Bradley Eberhard

Recorded July 26, 1940, by Robert Cornwall & Carita Doggett Corse in Sebring

(S1576, T86-255)

5. John Henry – Bill McLaughlin

Recorded April 1949 by Alton Morris in Jacksonville

(S1576, T86-227)

6. Lost Train Blues – Fred Perry & Glenn Carver

Recorded June 4, 1939, by John & Ruby Lomax in Raiford

(S1576, T86-226)

7. Orange Blossom Special – Chubby Anthony & Claude Bedenbaugh

Recorded April 30, 1970, in White Springs

(S1576, T77-214)

8. The Train – Reverend Dan Smith

Recorded August 29, 1975, in White Springs

(S1576, T79-14)

9. Track-Lining Song – The Gandy Dancers

Recorded May 30, 1993, in White Springs

(S1576, C93-13)

10. Hobo Story – Washboard Bill

Recorded May 27, 1994, by Keith Snyder in White Springs

(S1576, D94-24)

11. The Train – Moses Williams

Recorded November 27, 1977, by Dwight DeVane & Peggy Bulger in Waverly

(S1576, T77-300)

12. Old Forty – Richard Williams

Recorded May 27, 1978, by Dwight DeVane, Brenda McCallum & Stephen McCallum in Jonesville

(S1576, T78-328)

13. The Brakeman's Blues – Robert Dixon

Recorded May 26, 1979, in White Springs

(S1576, T83-99)

14. The Orange Blossom Special Don't Stop in Waldo Anymore – Don Grooms & Friends

Recorded May 29, 1988, in White Springs

(S1576, T88-56)

15. The Ballad of Casey Jones – Gamble Rogers

Recorded May 23, 1980, in White Springs

(S1576, T80-56)

16. Railroad Bill – Etta Baker

Recorded May 28, 1994, by Nancy Buchanan in White Springs

(S1576, D94-28)

17. Bound to Ride – Frank Lindamood

Recorded May 23, 1998, in White Springs

(S1576, C98-76)

18. The Weathered Old Caboose Behind the Train – Norman Blake

Recorded May 25, 2003, in White Springs

(S2034, CD03-24)

19. Midnight Special – "Spider" John Koerner

Recorded May 29, 2004, in White Springs

(S2034, CD04-58)

20. Bill Mason – Dale Webber

Recorded November 9, 2007, in White Springs

(S2034, CD07-58)

21. Wreck of the Old 97 – Jim Carrick

Recorded November 11, 2007, in White Springs

(S2034, CD07-15)

22. Orange Blossom Special – Gamble Rogers

Recorded May 24, 1985, in White Springs

(S1576, T85-2a)

Features

Territorial Legislative Council Records, 1822-1845

Documenting Florida's legislature prior to statehood

State and County Officer Directories, 1868-1969

Lists of Florida's state and county officials either elected or appointed between 1868 and 1969.

Guide to Military Records and the Wartime Experience

A guide to government records and manuscript collections relating to service members and the wartime experience.

Dust Tracks

21 tracks from Hurston's time documenting African American culture for the WPA in 1930s Florida.

History Day 2025

Resources for Florida History Day from the State Library and Archives of Florida.

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program