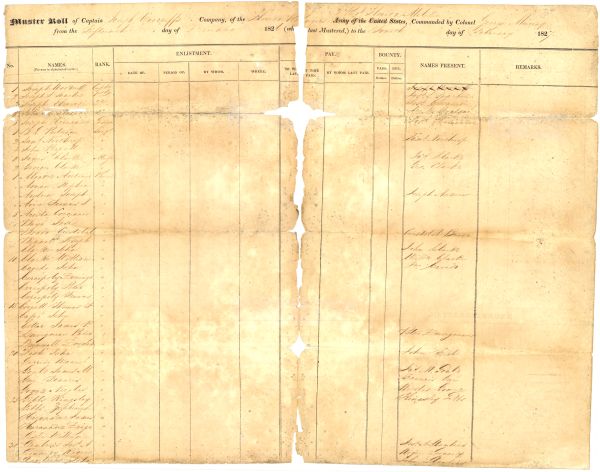

Florida Militia Muster Rolls, 1826-1900

About These Documents

These muster rolls, selected from three separate series of militia records in the State Archives’ holdings, are rosters of officers and men in Florida militia units dating from 1826 to about 1900. Some of the muster rolls were submitted by groups of volunteers asking to be recognized by the state government as militia units, while others are reports for units already in existence. A few of the earlier rolls document the activation of Florida militiamen for national service, particularly during the Second Seminole War (1835-1842). Most of the documents, however, are not related to military service in any particular war.

Militia units were forerunners of today’s National Guard—groups of civilians who volunteered for military service in the event of a war or sudden civil disturbance. Even in the territorial era, Florida law required men of a certain age to register for militia service, but this involuntary “enrolled militia” mostly existed only on paper. The most effective units were those that formed organically within the various counties in response to specific needs or emergencies. These groups would then appeal to the territorial or state government for official recognition.

Generally, each muster roll provides the name of the unit, the county or community where it was established, a date, and a list of the officers and men in the unit at that time. A boon for genealogists, some rolls also include physical descriptions of the members or information about their occupation. While these muster rolls are in no way systematic, they document a kind of military service that is sometimes overlooked when reconstructing the history of a family or community—service rendered in between wars rather than during one. They may also prove very useful for tracing relatives who do not appear in other traditional genealogical sources, such as federal or state census records.

The collection is not exhaustive. Muster rolls for units formed during specific conflicts, such as the American Civil War, are located in separate collections at the State Archives. Furthermore, some counties are not represented in this collection because they did not exist when the records were being created. For example, if you were searching for an ancestor who lived in what is now Pasco County in the 1870s, you would search for Hernando County records because Pasco's territory was part of Hernando until 1887.

Florida's Militia in the 19th Century

When Florida became a United States territory in 1821, its inhabitants became subject to federal laws requiring all able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 45 to enroll in their local militia. Militia units, for the most part, were managed strictly by the state or territory, only coming under federal control if pressed into national service. Florida’s territorial legislative council passed its first law organizing its militia in 1822. The law allowed for independent volunteer companies, but most of the structure was dedicated to maintaining an “enrolled” militia—one that able-bodied white men of the appropriate age theoretically belonged to at all times. African-Americans, including free black citizens, were not eligible to join. Postmasters, teachers, judges, ministers and a few other classes of individuals were exempt from service, but all others were supposed to register themselves with their local commander and periodically report for drilling and training. Officers were to wear the standard uniform of the United States Army and carry certain equipment, but non-officers could wear what they liked and were to provide their own weapons.

On paper, Florida’s militia was well planned, but in practice hardly any of the planning was ever actually executed. Very few units of the enrolled militia ever met for their required drill sessions, and hardly any of the reports called for in the law were turned in to territorial leaders. As a result, Florida did not turn in any report of its militia activities to the federal government until 1831, and even then its troop strength was too low and its reports too sporadic to qualify for the extensive federal aid needed to properly equip the men.

Volunteer units, however, did much better. The first volunteer militia company in territorial Florida was the Florida Rangers, established in St. Augustine on August 1, 1826. At least five more volunteer units appeared around the territory that year and received the governor’s recognition. As tensions between white settlers and Native Americans intensified in the late 1820s and early 1830s, the number of volunteer militia companies climbed considerably. When this conflict erupted into an all-out war in 1835, Florida militiamen fought alongside regular soldiers of the United States Army as well as protecting their local communities.

Florida’s militia also participated in the Mexican War, which broke out in 1846 following the United States’ annexation of Texas. Florida was asked to provide a battalion of troops, so state militia officers rounded up volunteers to go west. Only three companies actually served in Mexico; two others served briefly in Tampa.

As serious disagreements between the northern and southern states began pushing the United States closer to a civil war, volunteer units began appearing all around Florida, especially once Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860. Many of these companies were later absorbed into the Confederate Army or into Florida’s state reserves.

After the Civil War ended and Florida was readmitted to the United States with a new state constitution, the legislature established a new militia law. A few details had changed, including allowing African-Americans to serve for the first time, but the main problem that had plagued the state’s antebellum militia was still unresolved. Enrolled militia units were still treated as the primary component of the state’s troops, despite a lack of funding and enforcement for maintaining them.

In 1870, Adjutant General John Varnum tried a new policy that began to turn this situation around. Largely ignoring the enrolled militia, he placed advertisements in local newspapers around the state encouraging communities to establish volunteer militia units. He would supply arms and equipment, but only to units with uniforms, regular drills, and their own armory. The strategy had a profound effect. More than two dozen new volunteer units appeared in 1870—many of their muster rolls are included in this collection. After state representatives established a new constitution in 1885, the militia became even stronger. Funding increased, and the militia was reorganized into a new entity called the Florida State Troops (F.S.T.). Under the leadership of Adjutant General David Lang, the F.S.T. began looking more like the modern National Guard. Troops from across the state began meeting every summer to drill, even in years when the legislature did not appropriate funds to support the encampments. Local communities helped by providing food and supplies, and railroad companies even offered reduced fares for the traveling troops.

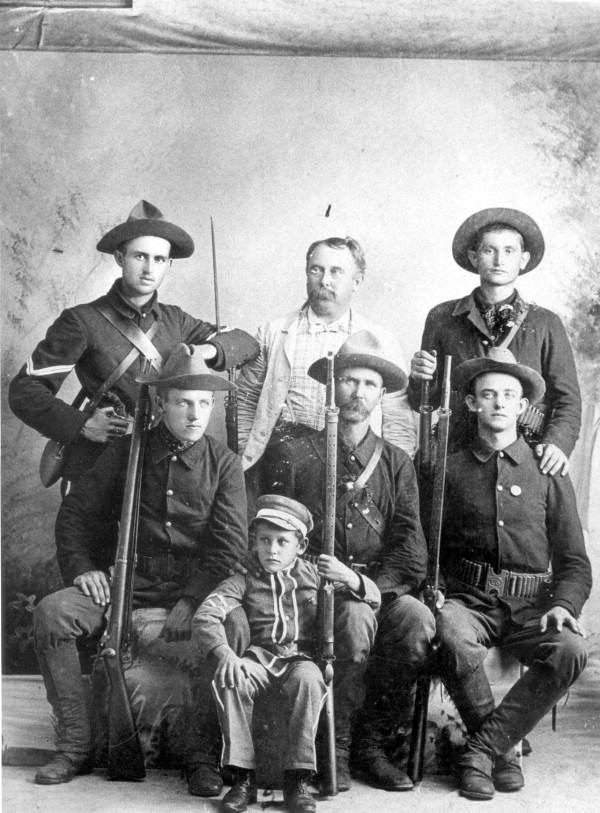

Columbia County volunteers for the

Spanish-American War. The civilian in

the back row is John Dudley Crabb,Sr.,

and the young boy in front is his son,

Roy Crabb (1898).

The Spanish-American War was the final major 19th-century conflict in which the Florida militia participated. The conflict was the culmination of Cuba’s prolonged effort to establish its independence from Spain. Even before the United States declared war on Spain in 1898, Floridians anticipated the likelihood of a fight, and state militia units stepped up their recruiting efforts to prepare. Once the war was on, the federal government asked Florida to supply one regiment with 12 companies of troops. The F.S.T. at that time consisted of 20 companies organized into battalions instead of regiments, and all 20 companies volunteered for the job. State leaders selected 12 companies for federal service, but the response to the national call for troops had been so overwhelming that there was little for the activated Florida units to do. Most never got any closer to the action than the port of embarkation at Tampa.

Following the Spanish-American War, the F.S.T. lapsed into a period of relative stagnation, with very little state funding and no summer encampments to boost morale and improve preparedness. In 1903, however, Congress passed new legislation establishing the modern National Guard with increased federal support. The new system essentially traded additional federal money to state militia organizations for a greater degree of standardization and federal control. Florida enthusiastically supported the new plan, becoming the first state to pass laws reorganizing its militia to comply with the requirements of the federal system. With funding from Washington and the able leadership of Adjutant General Joseph Clifford Reed Foster at home, the state troops continued to improve, and in 1909 they were renamed the Florida National Guard.

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program