Physician's Journal

Davidson's journal sheds light on the most pressing health needs of the day, or at least the diseases that Davidson felt most concerned about and able to treat. He included 17 entries devoted to gonorrhea, numerous recipes that address gastric disturbances, nine recipes for treating colic, five for itches, and 11 for diarrhea. Other serious illnesses Davidson devoted his thoughts to include one entry regarding hepatitis, four on pertussis (or "Whooping Cough"), one entry on epilepsy, six treatments for rheumatism, and three mentions each of typhoid and dysentery. Davidson also included treatments for everyday complaints including remedies for hair loss, toothache, and several suggestions to ease constipation.

The Davidsons of Gadsden County

John M. W. Davidson was born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, in 1801. He was the grandson of John Davidson, a brigadier general for the colonies during the Revolutionary War and successful planter and community leader whose other descendents donated the land used for Davidson College among other lasting contributions to the state of North Carolina.

The grandson, Dr. Davidson, married Mary J. Sylvester, the daughter of a prominent South Carolina family, and they had four daughters and five sons before her death in 1855. He moved to Florida along with scores of other emigrants from North and South Carolina drawn by the area's reputation for productive—and available—farm land. He settled in Gadsden County in 1828 before moving into the new town of Quincy some years later.

While operating a successful medical practice, Davidson maintained extensive agricultural interests, likely devoting acres to the county's most profitable commodity, tobacco. As a planter, Davidson's investments were intertwined with the slave economy of the period. He owned as many as 30 slaves at one time, with 18 recorded in the 1860 census. In Quincy, Davidson also owned and operated a pharmacy. At least one of his sons continued the family trade as a professional pharmacist in the town. [iii]

In the journal, Davidson makes no distinction regarding race or economic background between patients that he has treated. Southern physicians were often called on to treat African-American and white patients, and because physicians were in such high demand, their services would often have been required for people of all social statuses and means.

We know from other sources, such as a fee schedule developed by Davidson and his fellow Gadsden County doctors, that he was called upon to perform a variety of dental and bodily surgeries including tooth extraction, limb amputation, and "trephining," or the removal of sections from the skull to relieve pressure from blood build-up. He and his colleagues had also agreed upon fees for attending labors, introducing catheters, performing enemas, operating on hare lips, and performing other therapies such as "cupping," a technique in which air is evacuated from a cup placed on the skin to increase localized blood flow. [iv]

Davidson was an ardent Whig until the demise of the party. He then became a Democrat and was elected as a delegate to the 1860 convention in Baltimore. After the election of Lincoln as president, Davidson accepted the inevitability of conflict, but like many other leading citizens was fearful of the consequences of the war on the South's economy. While he had supported Florida's statehood since moving to the territory three decades earlier, he was also a devoted believer in the Union. However, like many of his contemporaries, Davidson felt that the sovereignty and social customs of the southern states were under threat. [v]

All five of Davidson's sons served in the Confederate Army, including J. Edward, who served as a surgeon and medical purveyor to the Confederate Army. Before rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the 6th Infantry, Robert H. M. Davidson was a state representative and senator for Gadsden County, after attending the University of Virginia Law School. After the war Robert represented Gadsden County at the Constitutional convention of 1865. The youngest son, Edgar Lee, was just 16 years old when he went to the Everglades during the War, assigned to troops guarding the Seminoles. [vi]

When war came, William left his work as a pharmacy clerk to become a lieutenant of the First Regiment Volunteer Infantry of Florida before advancing to the rank of captain and aide-de-camp to General J. Patton Anderson. After the war he became a railroad agent and general manager of the Florida Central & Western Railroad. Mrs. Mary Sylvester Davidson died in 1855, but in addition to Dr. Davidson, she was survived by all five sons and four daughters: Martha, the eldest child, Sarah F. H., Mary J. L., and Alice.

Dr. Davidson and the Modernization of Medicine

John Davidson's career spanned the beginnig of the rise of orthodox medicine in the United States. His writing demonstrates the need of 19th century physicians, particularly those in rural areas of the country, to adapt their training to where they practiced. Physicians accommodated local traditions, utilized whatever supplies and ingredients were available to them, and developed personal relationships with patients and the communities where they lived and practiced. By the last decades of the 19th century, professional medical practitioners had cemented their positions as the definitive source of high quality medical care in the United States, as well as defenders of science and advocates of even greater professionalization.

Although statewide medical organization was slow in coming to Florida, local and county doctors often regulated themselves and cooperated to ensure best practices. Dr. Davidson was a member and chair of the Physicians of Quincy group. The group coordinated fee schedules for treatments, surgeries, births, and travel expenses, and published their signed agreements in each physician's office. [vii]

For physicians in the early 19th century, before the nature of many diseases became more widely understood and the greater development of epidemiology as a science, treating the patient was more important than the disease. Physicians often considered intimate knowledge of an individual's circumstances and familiarity with case histories as more important even than their own professional experience with certain diseases.

Physicians in the antebellum South injected their own appreciation of abstract, scientific medicine and medical training with a strong sense of southern individualism, respect for their patients' personal lives, and respect for the traditions of the locality where they practiced. Medical historian Steven Stowe terms this phenomenon "country orthodoxy." According to Stowe, Southern doctors consequently tended to value "experience" over training, although one complemented the other. On plantations and in isolated communities, local and private healers knew the people and environment intimately, and physicians similarly added the experiences with individuals and the diseases afflicting a region to their abstract knowledge bases. [viii]

In Florida's earliest years as a U.S. territory, self-appointed local community doctors, housewives, and slave healers administered medicines as they could, using herbs gathered from the area and what ingredients they could purchase along with turpentine, spirits of niter, and other solvents and solutions. "When home remedies failed, the doctor was summoned. He brought all medicines he thought necessary, and before leaving the bedside gave particular directions for the administration of every pill, powder, or liquid." [ix]

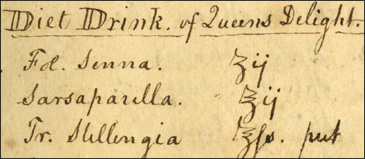

Davidson includes in the journal citations for the medical reference works he consulted for new ideas and suggestions for prescriptions and treatments. Davidson's effort to continue his learning and his regular consultation of national and international medical publications demonstrated his commitment to orthodox medicine. Employing apothecary symbols to denote measurements throughout the journal, Davidson demonstrated at least some training in pharmaceutical preparation. The writing style varied some over the course of the journal, and his notations seems to have also reflected what source material he was using. During the two years he spent writing the journal, Davidson scrupulously ordered most of the entries and appears to have edited some with later information or corrections.

!["Pertussis [Recipe]. Carb. Potass --------- [1 dram]. Cocus -- 10. gr Aq. fervent -- O [half] for an infant."](/fpc/memory/Collections/physicians-journal/images/excerpts/page_119.jpg)

Medicine in early-19th century America was a wide-open field. Not only could nearly anyone practice it who could convince other people to serve as patients, but most people had no firm idea what sound medical practice actually was. As historian Cathy Luchetti describes the situation, "Any man who worked with his hands and carried tools in a leather bag could set up a practice, dispensing pills and potions, binding bones, and profiting from the sale of homemade nostrums." [x]

On the American frontier, quacks and practitioners of strange fads were more common than trained physicians. While local wise men and women, or "grannies" as they were often called, were essential for filling the gap between the medical needs of the community and the number of available caregivers, many were no more qualified than any other lay person. Doctors who had received some training were often on the frontier seeking their own fortunes, like the quacks, charlatans, and potion vendors. In 1840, as few as one-quarter of practicing male physicians in the country had graduated from medical schools. As the field of medicine was not a source of great income even for the most competent practitioners, doctors often viewed medicine as an afterthought or complement to their primary occupation, such as running a store or farming. [xi]

Davidson's journal sheds light on the use of homeopathic and folk remedies by physicians still common in rural areas. The modern medicine and doctor-patient relationship that most people are familiar with today reflects more than a century of the dominance of "allopathic" medicine, or the combating of disease by addressing symptoms with specific treatments meant to cause different reactions than the perceived disease itself. [xii]

Physicians had to manufacture their own medicines and Davidson's journal shows a wide array of herbal and chemical components he relied upon for treatments, in addition to foodstuffs and staples such as wine and milk. For rural southerners, the preparation of herbal remedies and supplies for the treatment of common ailments was part of everyday life. The South as a whole was underserved by trained medical professionals and local healers, and everyday people used whatever resources and means were available to address the medical needs of their families, the community, and themselves. [xiii]

Davidson's journal shows some of the thoughts, methods, and demands of a pioneer physician in the ante-bellum South. The journal remains as evidence of the working life of a founding father of a Florida county. It opens a window to a very different time for both a profession and a community, when the availability of material goods—even medical necessities—and the established beliefs and practices of professionals were less certain, but the need to work, serve, and help others was as clear as it is today.[xiii]

[i] David A. Avant, Jr., Illustrated Index: J. Randall Stanley’s History of Gadsden County, 1948, Tallahassee, Florida: L’Avant Studios, 1985, p. 33.

[ii] Miles Kenan Womack, Jr., Gadsden: A Florida County in Word and Picture, Quincy, Florida: Gadsden County Bicentennial Commission, 1976, p. 44-52.

[iii] Rowland H. Rerick, Memoirs of Florida, Atlanta: Southern Historical Association, 1902, p. 505, and E. Ashby Hammond, The Medical Profession in 19th Century Florida: A Biographical Register, Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida, 1996, p. 155-157.

[iv] Womack, p. 61.

[v] Excerpts of 1860-1861 diary of Dr. John M.W. Davidson from Womack, p. 64-65.

[vi] Avant, p. 98; Womack, p. 298-299; Hammond, p. 157-158.

[viii] See Steven M. Stowe, Doctoring the South: Southern Physicians and Everyday Medicine in the Mid-Nineteenth Century, Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

[ix] Webster Merritt, A Century of Medicine in Jacksonville and Duval County, Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press, 1949, p. 8.

[x] Cathy Luchetti, Medicine Women: The Story of Early-American Women Doctors, New York: Crown Publishers, 1998, p. 7.

[xi] Luchetti, p. 8.

[xii] Dr. Jean Elmiger, Rediscovering Real Medicine: The New Horizons of Homeopathy, Boston: Element, 1998, p. 14-21.

[xiii] Weymouth T. Jordan, Herbs, Hoecakes, and Husbandry: The Daybook of a Planter of the Old South, Tallahassee, Florida: The Florida State University, 1960, p. 21.

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program