Description of previous item

Description of next item

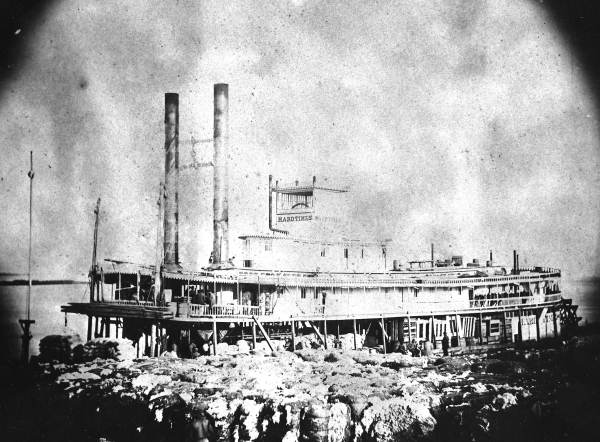

Corn, Not Cotton in the Civil War

Published February 2, 2013 by Florida Memory

Corn, not Cotton

Even though the North produced more agricultural goods than the South during the Civil War, at the beginning of the war in 1861, few observers would have predicted that the South, with its overwhelmingly agricultural economy and seemingly endless supply of slave labor, would find it difficult to provide adequate food supplies to its soldiers and citizens.

However, a number of factors produced food shortages early on in the war and especially by 1863. By then, the continuing and growing absence of men from their farms due to military service, the impressment of food and slaves for the use of the Confederate Army, a tightening Union naval blockade, and a poor transportation system combined to spark bread riots in many Southern cities and led to increased misery on the Confederate home front, where poor families struggled to feed themselves.

Florida was not immune from these conditions. Although the state's location far away from the main fighting fronts meant that the vast majority of its agricultural land was untouched by the enemy, most of Florida's white men of military age were serving in the Confederate Army outside of the state by the summer of 1862. This meant that they could not be at home working to feed their families. In addition, by 1863, most of Florida's ports were either occupied or blockaded by the U.S. Navy, so few outside supplies reached the state. Of course, blockade-runners succeeded in bringing goods to Florida's shores, but most of these items were either luxury goods or weapons, not provisions that could feed Florida's poor farm families.

Given the swift decline in value of Confederate currency during the war, planters found they had to rely on the one crop that was still valuable enough in itself to be used to purchase needed supplies and the specialty goods that the blockade-runners provided. That crop was cotton.

Soon after the war began, individual Confederate states adopted an unofficial embargo on cotton sales and shipments to Europe. Since the textile mills of Britain and France depended on Southern cotton to produce their cloth, the embargo would, so it was reasoned, force those European counties to break the Union blockade and recognize the legitimacy of the Confederate government. Unfortunately for the South, this scenario never played out: a glut of cotton on the world market in 1861-1863 allowed Europe to get by on existing cotton stockpiles, and Britain, the world's strongest power, turned to cotton grown in its vast Indian empire. Although Europe was not buying up Confederate cotton, and Southern families needed corn, not cotton to fill their bellies, the crop was too valuable a commodity for planters to curb its production.

Faced with a food crisis, some Southern governors in the cotton-producing states passed legislation to force planters to plant less cotton and grow more corn to feed the general population as well as the ever-hungry Confederate armies. Florida's governor, John Milton, was one of the most vigorous proponents of increasing food production at the expense of cotton. Even though Florida exported cattle and corn to the rest of the Confederacy east of the Mississippi, Milton feared that increased Confederate dependence on Florida agriculture and the increasing difficulty for poor Floridians to produce or purchase enough food would result in food shortages within the state.

After the legislature refused to take up planting restrictions in its last session, Governor Milton tried to appeal to the planters' patriotism. On February 24, 1863, he issued a proclamation to Florida's planters that called on their sense of honor to cut cotton production for the sake of the Confederate war effort and the lives of women and children. Given the public's loathing of war profiteering, Milton tried to instill guilt in those planters who "have been infected by the evil spirit of gain … and has distinguished them as despicable wretches, who would sacrifice the Confederate States and distress women and children to glut their insatiate greed for dollars and cents." Despite this and other appeals, Milton continued to struggle with the issue of food production for the rest of the war. Florida proved to be an essential source of supply for the Confederate Army, but, as Milton feared, this left less for Floridians back home.

For the history of Florida's economic role in the war see Robert A. Taylor, Rebel Storehouse: Florida's Contribution to the Confederacy (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2003).

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Corn, Not Cotton in the Civil War." Floridiana, 2013. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257945.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Corn, Not Cotton in the Civil War." Floridiana, 2013, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257945. Accessed March 9, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2013, February 2). Corn, Not Cotton in the Civil War. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257945

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program