Description of previous item

Description of next item

Detour to Liberty: Black Troops in Florida During the Civil War

Published February 2, 2013 by Florida Memory

In his annual message to the Florida General Assembly on November 17, 1862, Governor John Milton pointed to Abraham Lincoln's Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which proclaimed freedom for all slaves living in areas of the country still in rebellion by January 1863, as a plot to "subjugate Florida . . . and to colonize the State with negroes . . . ."

The proclamation was, Milton argued, nothing less than "the means the most terrific which could be devised to alarm the people of the South . . . ." As Milton feared, the Emancipation Proclamation came to pass on January 1, 1863, but the alarm that sounded across the South was soon compounded by the Union's deployment of black troops against the Confederacy.

Beginning in March 1863, Florida was the site of some of the earliest operations of black regiments, which became an essential part of Union operations in the state until the end of the war.

As early as November 1862, black companies conducted raids against salt works and saw mills along both sides of the coastal border between Georgia and Florida. These attacks were the outgrowth of the U.S. War Department's order of August 25, 1862. That order allowed the creation of a limited number of black units within the U.S. Army's Department of the South, which was responsible for military operations along the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

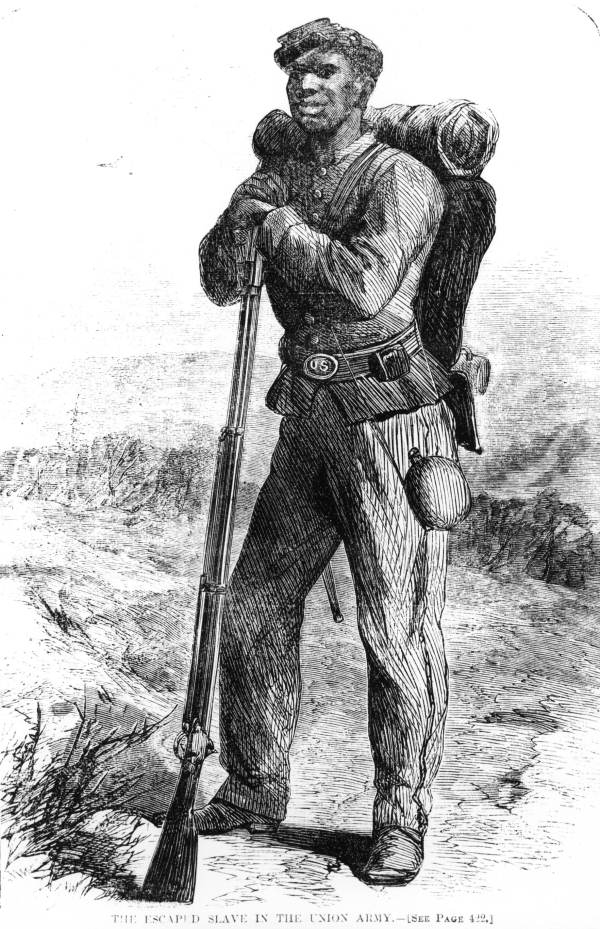

The black soldiers in the raids consisted of men from the coasts of those states who had either escaped slavery by running away or by Federal occupation of their masters' lands. The black companies came from the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment, one of the first black units organized during the war. Under the command of Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a prominent Massachusetts abolitionist, the 1st South Carolina, like all black regiments during the war, were led by white officers.

In January 1863, Higginson received permission to lead several companies of his regiment on a raid up the St. Mary's River along the Georgia-Florida border. This raid was followed by a much more substantial operation launched in March 1863 against Jacksonville. Higginson and Brigadier General Rufus Saxton convinced the commander of the Department of the South, General David Hunter, to order the 1st South Carolina, along with the nucleus of what would become the 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, to launch an expedition into northeast Florida with the objective of occupying Jacksonville and conducting raids along the St. Johns River. Higginson and Saxton argued successfully to Hunter that such an expedition would open up important opportunities for the North: the raid would support and secure Unionist sentiment in northeast Florida, which was known to be the home of many transplanted Northerners; a Union occupied Jacksonville would act as a magnet for escaped slaves, who could in turn be recruited as soldiers; and a successful operation carried out by black troops would certainly increase the likelihood that the North would come to support the large-scale recruitment of blacks into the U.S. Army. Furthermore, the Union already had a presence in northeast Florida which could only increase the expedition's chances of success: the Union occupied Jacksonville for brief periods in March and October 1862, and the U.S. Navy, which already had blacks in its service, held Amelia Island and St. Augustine since the spring of 1862 and conducted missions on the St. Johns.

With these factors in its favor, the black units moved to occupy Jacksonville on March 10, 1863. Higginson's men captured a town that was undefended by the Confederates, whose strategy, given the small number of troops at their disposal, was to protect the rail lines to the west of Jacksonville and prevent Union advances into the interior beyond the St. Johns until such time when reinforcements might allow them to retake the city. The Union troops quickly occupied the town and began to take up defensive positions on the outskirts. It was the largely untrained men of the 2nd South Carolina regiment that ran into the first Confederate resistance. A combined force of Rebel cavalry and infantry engaged a company of the 2nd South Carolina men on the morning of the second day of the occupation. Although they had never fought a battle, the soldiers did not panic. They returned fire and conducted an orderly withdrawal to more secure positions within supporting range of naval gunboats. The black regiments remained in control of Jacksonville, eventually reinforced by a couple of white soldiered regiments, until March 29. During that time they also conducted raids up the St. Johns as far south as Palatka. The short duration of the Jacksonville expedition was due to General Hunter's decision to withdraw the troops for use in South Carolina, where the Union was preparing an assault on Charleston. Higginson was of course upset by this decision and believed that it might have been due to resistance among some top officers in Hunter's command to the idea of creating black units in the first place.

At any rate, the 1st and 2nd South Carolina returned to their home base. In 1864, both units were re-designated the 33rd and 34th U.S. Colored Infantry regiments respectively and continued to serve in the Department of the South for the duration of the war. Although some in the North argued that the expedition to Florida had been a failure, this view was countered in the press by many newspapers that praised the operation as proof of the viability of employing black soldiers in the war. The expedition almost certainly influenced President Lincoln and the War Department's decision on March 25, 1863, to launch the large-scale recruitment of blacks into the U.S. Army. This order led to the wholesale creation of black regiments, which became an essential part of the Union war effort for the rest of the conflict.

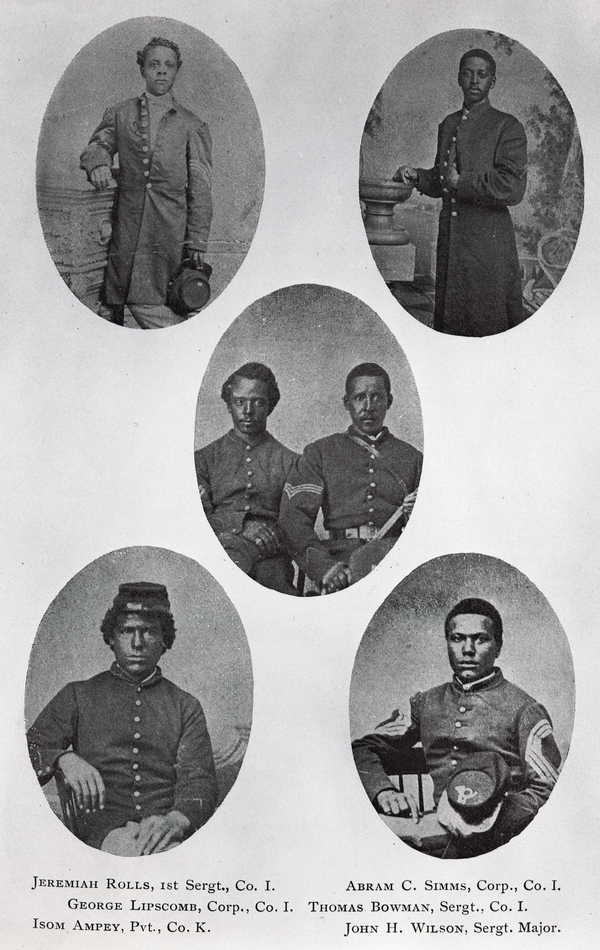

The 1863 expedition was not the last time that black troops occupied Jacksonville. In February 1864, the Union launched what would be the war's largest military campaign in Florida. Designed to interrupt the supply of cattle and goods from the state that were destined for Confederate armies outside of Florida, add more escaped and freed slaves to the ranks of the U.S. Army; and possibly bring Florida back into the Union as a reconstructed free state, the northeast Florida campaign of 1864 consisted of some 7,000 Union troops, including three black regiments: the 1st North Carolina Colored Infantry, the 8th U.S. Colored Infantry (USCT), and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. The 54th had already distinguished itself on the ramparts of South Carolina's Fort Wagner during the unit's now famous assault on that Confederate bastion in July 1863. Unlike the 54th, however, the two other regiments had never been in combat, and the 8th USCT had not even completed its training when it arrived in Florida along with the rest of the Union troops on February 7, 1864.

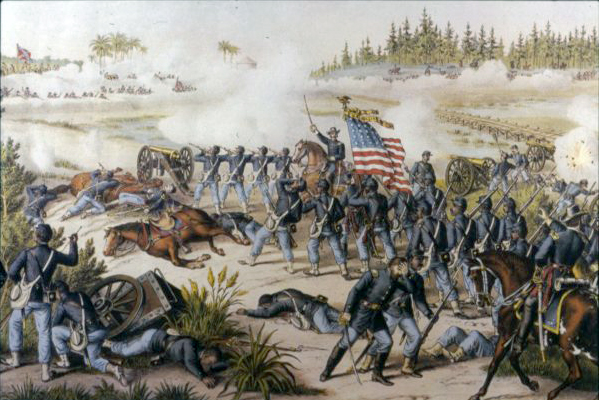

Leaving about 1,500 men to secure Jacksonville and conduct other missions, the main Union force of 5,500 troops under the command of Brigadier General Truman Seymour began a march on February 20 west towards Lake City and the Suwannee River beyond. East of Lake City the Federals ran into advanced elements of a Confederate force of 5,000 men that established defensive positions outside of Lake City at Olustee, a station along the Florida, Atlantic & Gulf Railroad. The battle, which lasted through the afternoon of February 20th, was a particularly bloody encounter that ended in a Confederate victory and a humiliating Union retreat back to Jacksonville.

The more experienced 54th Massachusetts as well as the 1st North Carolina played an important role in the battle by holding back the Confederate advance as the rest of Seymour's regiments withdrew. One of those regiments, the 8th USCT, experienced some of the day's heaviest fighting. Its untested ranks were ordered forward and ran into a storm of Confederate fire. Stunned, confused, and frightened, the men of the 8th USCT behaved as many better trained white units behaved in their first battle. Many of them ran or tried to find cover, while others were able to compose themselves and return the Confederate fire. At the end of the battle, the 8th USCT lost more men than any other Union unit: forty-nine killed, 188 wounded, and 73 missing. Of these missing, several became prisoners and were eventually transferred to the infamous Confederate prisoner of war camp at Andersonville, Georgia. Others may have faced an even worse fate. Several postwar accounts, mostly from Confederate sources, recalled that individual Confederate soldiers killed some of the wounded and captured black soldiers. Olustee, or the Battle of Ocean Pond (the Northern name for the battle), turned out to be one of the war's most horrendous encounters for the Union's black soldiers.

After Olustee, black troops continued to play an important role in Union operations in Florida. In September 1864, they made up part of the force that attacked Marianna, Florida, and on March 6, 1865, black soldiers formed the mass of the Union troops that engaged the Confederates south of Tallahassee at Natural Bridge. The Union lost the battle and was denied the opportunity to capture Tallahassee during the war. A little over two months later, however, black troops marched into Florida's capital as part of the Union occupying force that received the formal surrender of Confederate Florida on May 20, 1865.

Today, while the operations of black troops are better known in theaters of the war such as South Carolina (the assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863) and Virginia (the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864) directed at the heart of the Confederacy, the actions of black troops in Florida, although less famous, were just as crucial to establishing the importance of black units in the Union war effort. Although the direct path to Union victory and black freedom pointed to Atlanta and Richmond, the route included many detours, like Florida, which led to ultimate emancipation.

For the operations of black troops in Florida see Stephen V. Ash, Firebrand of Liberty: The Story of Two Black Regiments that Changed the Course of the Civil War (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008); Arthur W. Bergeron, Jr., "The Battle of Olustee" in John David Smith, ed., Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); and David J. Coles, "Shooting Niggers Sir": Confederate Mistreatment of Union Black Soldiers at the Battle of Olustee" in Gregory J. W. Urwin, ed., Black Flag Over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004).

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Detour to Liberty: Black Troops in Florida During the Civil War." Floridiana, 2013. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257948.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Detour to Liberty: Black Troops in Florida During the Civil War." Floridiana, 2013, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257948. Accessed March 9, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2013, February 2). Detour to Liberty: Black Troops in Florida During the Civil War. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257948

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program