Description of previous item

Description of next item

Florida and the Civil War (December 1863)

Published December 12, 2013 by Florida Memory

A Stickney Situation

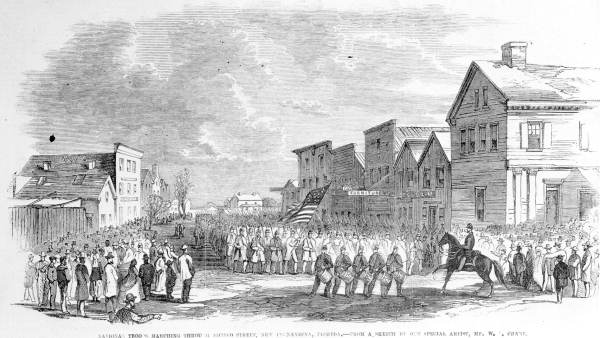

The war in Florida changed little in 1863. Despite a third, brief Union occupation of Jacksonville in March most military activity in the state consisted of Federal raids on the coastal salt making industry and the continuing Union blockade of Florida ports, many of which had been occupied by Federal troops since 1862.

By December 1863, while the military situation remained calm, politics in Union occupied areas of Florida were anything but peaceful. As 1864 approached, so too did the Union presidential election. Although Florida was far from being a Union military priority, for the first couple months of 1864 it would briefly be the focus of high power politics.

President Abraham Lincoln and his most prominent potential presidential rival within the Republican Party, Salmon P. Chase, considered the possibility of bringing a portion of the state back into the Union in time for its Republican delegates to support their respective candidacies. During this political drama, the most important player on the ground in Florida was Lyman D. Stickney, a Florida Unionist whose politics began and ended with self-interest.

Stickney’s prospects in Florida began in 1860, when he arrived in the state promoting a colonization scheme to bring agricultural development to largely untamed south Florida. After Florida’s secession and the failure of his colonial venture, Stickney, a Vermont native, made his way to the Federal enclave of Key West, where he quickly proclaimed his loyalty to the Union. Leaving Key West with “an unpaid hotel bill of $144.00” in June 1861, Stickney moved to Washington, D.C., and insinuated himself into government circles as an “expert” on all things Florida.

A talented lobbyist, whose cause was his own fortune, Stickney acquired a potentially powerful and lucrative position in July 1862, when President Lincoln, on the recommendation of Secretary of the Treasury Salon P. Chase, appointed him one of three direct tax commissioners for Florida.

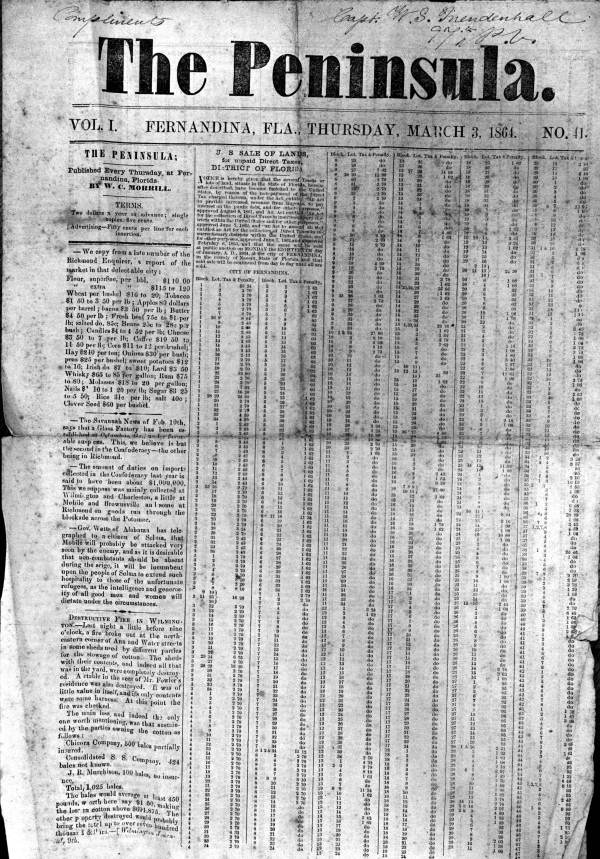

The federal Direct Tax Law was a weapon of economic warfare. Passed in June 1862, the law called for the confiscation of any real property in Rebel held territory whose owners failed to pay the tax. The Direct Tax Law created three tax commissioners for each Rebel state where Union forces occupied a portion of the state. The commissioners would access the value of the real property within Federal control and impose a tax. Given that pro-Confederate citizens within these areas had usually fled or were unwilling to pay the tax, the tax commissioners ended up seizing their property and either selling or leasing it to Unionist Floridians or recently arrived Northern immigrants.

After his appointment, Commissioner Stickney wrote a number of letters to President Lincoln supporting the appointment of various men to federal positions in Union held areas of Florida and proclaiming his loyalty and “deep interest in the future destiny of Florida, of which I am a citizen…” Stickney was an enthusiastic supporter of the Union expedition to Jacksonville in March 1863 (see “Detour to Liberty: Black Troops in Florida during the Civil War” and “Florida and the Civil War: March 1863”).

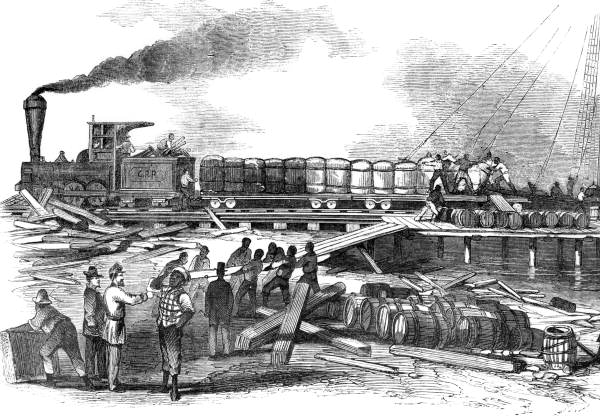

By the time the expedition set sail, he had established himself as a silent partner in a general store in Fernandina and shipped goods to the store at government expense under the cover of the Direct Tax Commission. He hoped the expedition would lead to the permanent Union occupation of Jacksonville and northeast Florida. In such an eventuality, he saw endless opportunities for profit, including trade in cotton and turpentine. Even though the expedition proved short-lived, Stickney did not relent.

On December 2, 1863, as he was about to board a ship for another trip to Fernandina, Stickney urged Lincoln “to authorize the loyal people of Florida to organize a state government in conformity with the Constitution and laws of the United States.” He guaranteed that “the work of restoration will be speedy and permanent” if the president would allow “every person of lawful age, and not disqualified by crime, whose fidelity to your administration and your proclamation of freedom is unquestioned be a voter…”

If feasible, the early restoration of Florida to the Union, even if it was only a small portion of the state, could serve the Union cause as a magnet for discontented and Unionist Southerners living in Florida and Georgia as well as for escaped slaves, many of whom were now filling the ranks of the Union’s increasingly numerous black regiments.

Front page of The Peninsula, March 3, 1864, list indicates property sold for failing to pay the Federal direct tax

At the same time, a restored Florida could make a difference in the 1864 presidential election by throwing its Republican Party delegates to either Lincoln or Stickney’s benefactor, Secretary of the Treasury Chase, whose presidential ambition was one of the worst kept secrets in Washington. Finally, and most importantly for Stickney, a Florida returned to the Union held endless possibilities for his own advancement, either financially or politically, as he would doubtless be one of the key leaders in a new, loyal Florida.

The pursuit of a reconstructed Florida was one of the motivating factors in the Union decision to mount yet another expedition to Jacksonville in February 1864. This expedition resulted in the Federal defeat at Olustee on February 20th. The Battle of Olustee, or Ocean Pond as it was known in the North, ended Stickney’s dream of a Florida restored to the Union. Florida would not play a role in the presidential election of 1864, which saw Lincoln’s easy capture of the Republican nomination over Chase.

Stickney’s summer of 1864 was considerably less fortunate than Lincoln’s. In July, a treasury department report criticized Stickney for being almost constantly absent from his duties in Florida and implicated him in financial and political corruption schemes. Indicted in 1865, Stickney, slippery as ever, managed to escape punishment and restart his professional life in the postwar economy.

The quote about Stickney’s Key West hotel bill comes from David J. Coles, “Far from Fields of Glory: Military Operations in Florida, 1864-1865,” (Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University, 1996). The Stickney quotes are found in two of his letters to Lincoln dated October 27, 1863 and December 2, 1863; the original letters are located in the Robert Todd Lincoln Collection, Library of Congress.

For Sitckney’s role during Union military operations in Florida see Stephen V. Ash, Firebrand of Liberty: the Story of Two Black Regiments that Changed the Course of the Civil War (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008). A copy of the Florida Direct Tax Commission records are located in Record Group 101, Series 161, United States Direct Tax Refund Records, 1891-1901, State Archives of Florida.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Florida and the Civil War (December 1863)." Floridiana, 2013. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295144.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Florida and the Civil War (December 1863)." Floridiana, 2013, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295144. Accessed February 13, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2013, December 12). Florida and the Civil War (December 1863). Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295144

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program