Description of previous item

Description of next item

Florida and the Ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment

Published March 3, 2017 by Florida Memory

Florida’s diverse and heavily populated electorate has written its longstanding reputation as a political battleground state — in the 1970s, one of the biggest battle facing state lawmakers was the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The amendment proposed that “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on account of sex,” and stirred ongoing controversy between leaders of the women’s liberation movement and anti-feminist activists. Though it ultimately never passed, Floridians’ response to the ERA mirrored the sharp national divide over the amendment’s message on gender equality.

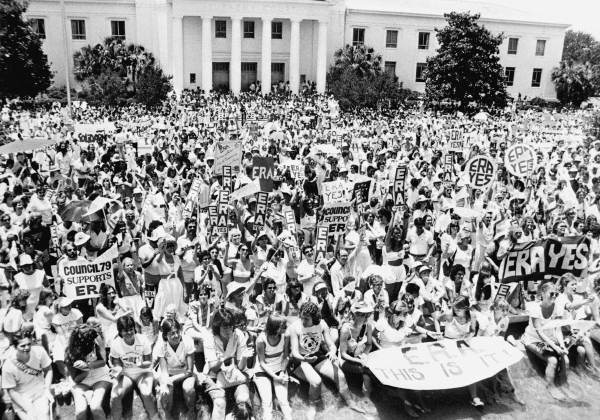

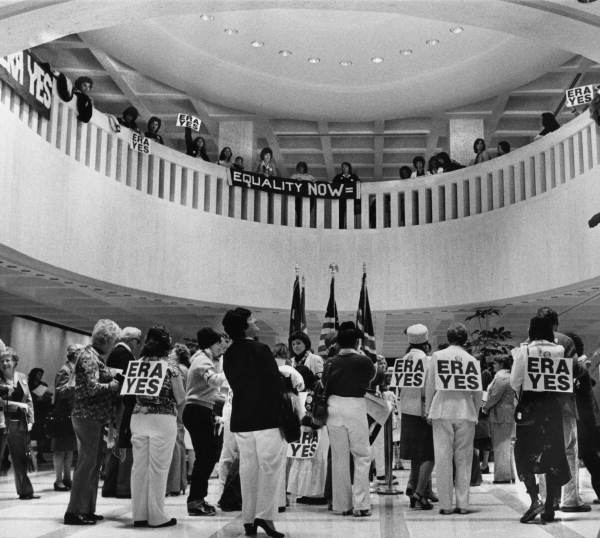

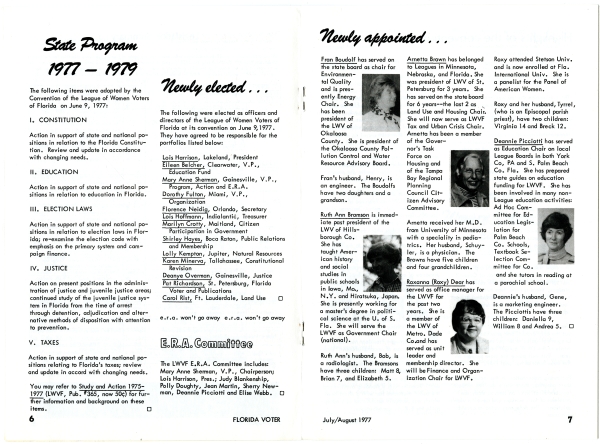

ERA supporters rally outside the Florida Capitol Complex to kick off ERA Awareness Week, November 1981. Their efforts were aimed at pressuring lawmakers to ratify the amendment during the 1982 Legislative Session.

In 1923, three years after American women won the right to vote, National Woman’s Party President Alice Paul wrote and introduced the ERA to U.S. Congress. Only three short sentences long, its intent to eliminate all sex-based legal distinctions was clear, but it failed to gain unanimous political support from the outset. Some feminists viewed the ERA as the surest avenue for eliminating gender discrimination, but opponents countered that it would undermine hard-fought legal protections for women such as maternity leave and revised labor laws (Muller v. Oregon, 1908). As was the trend in many states in the years after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, the vigilant political activism that had won women the right to vote died down in Florida. Though there had been a suffrage movement in Florida in the 1910s, the state constitution did not officially adopt provisions for women’s voting rights until 1969.

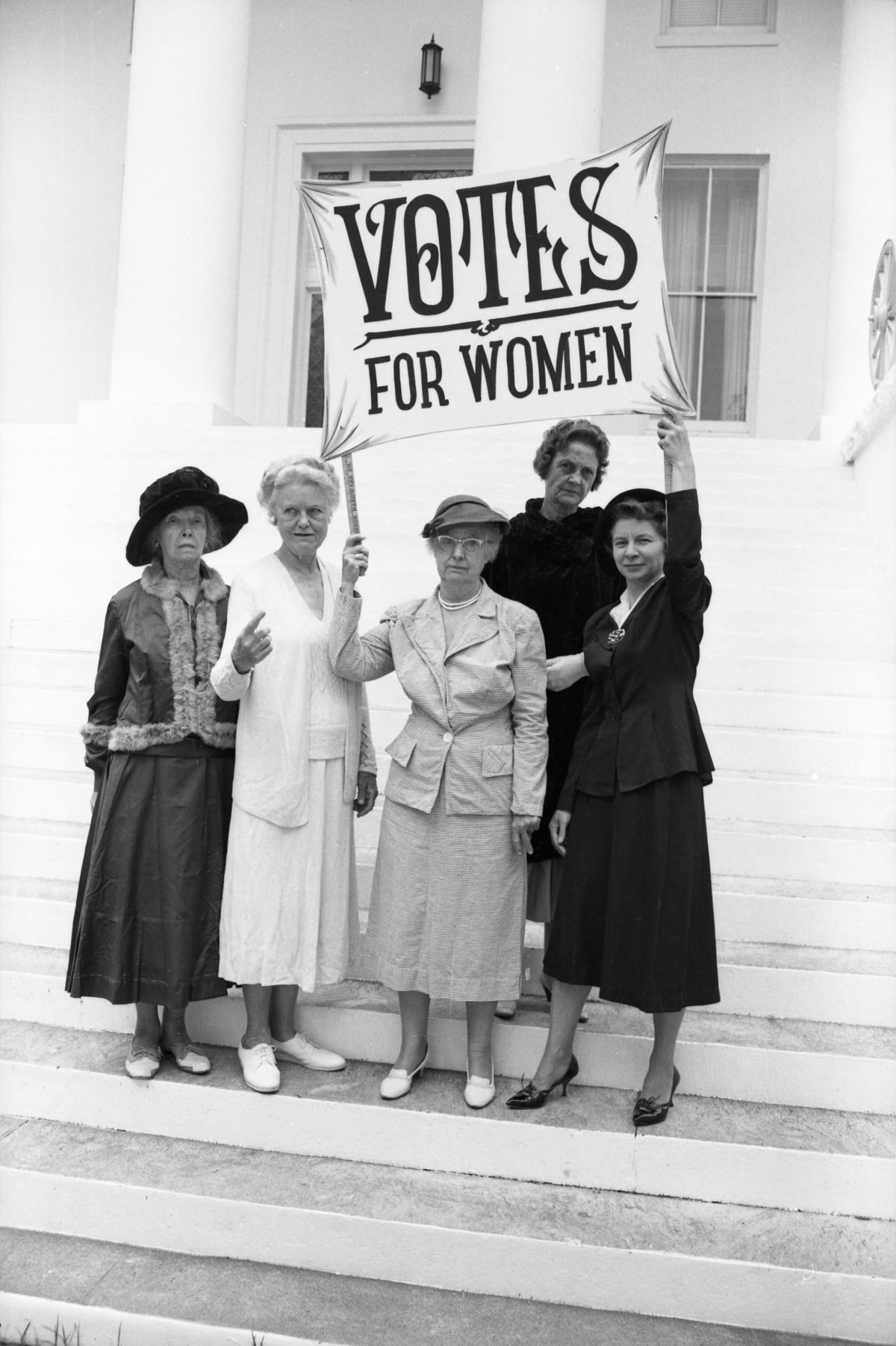

League of Women Voters recreating scenes of suffrage activism on the steps of the old Florida Capitol, 1963.

For over four decades after Alice Paul drafted the ERA, it languished unaddressed in a congressional committee, until the 1960s when the women’s liberation movement strengthened renewed interest in the measure. Both the federal Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 addressed gender discrimination. Both the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 addressed gender discrimination on the federal level. At the state level, population increases and legislative reapportionment in 1960s diversified legislative representation and sparked the passage of more progressive legislation–lawmakers barred sex-based discrimination in divorce, custody and child support cases in Florida. In 1966, Betty Friedan, Pauli Murray and many other feminists co-founded the National Organization of Women (NOW) to enforce these new laws and further advocate for women’s equality. Despite marked gains in addressing some of the specific issues, NOW stressed that the new laws contained insidious loopholes, and insisted that the ratification of the ERA was the best solution for achieving true gender equality. “Existing laws are not doing the job,” said Florida State Senator Betty Castor, echoing the sentiment of ERA proponents across the nation.

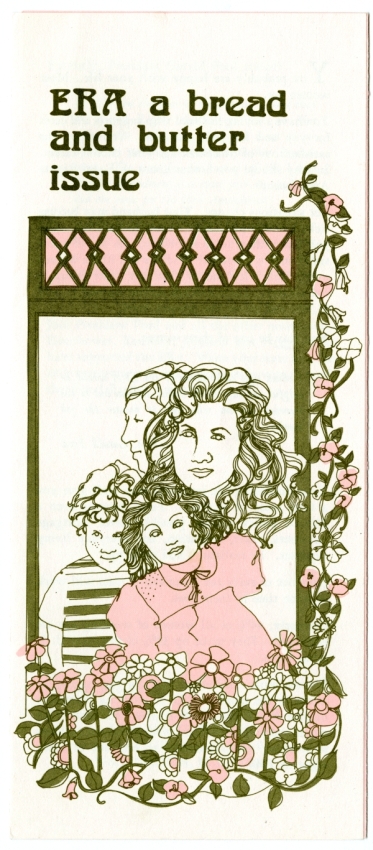

A brochure produced by the American Association of University Women encouraging women to support the Equal Rights Amendment, ca. 1974.

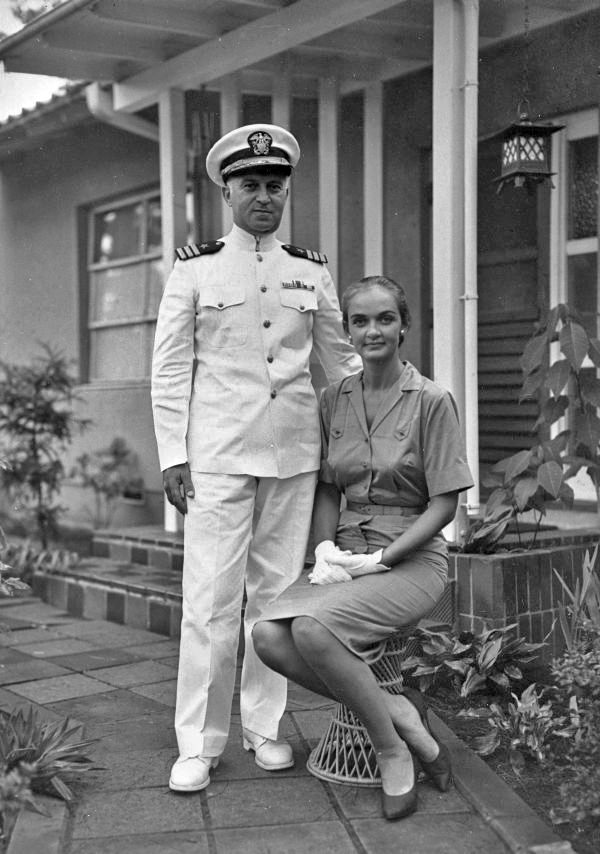

One of the most outspoken members of NOW was pioneering feminist Roxcy O’Neal Bolton from Miami. Bolton launched the Miami Chapter of NOW in 1966 and was elected national vice-president of NOW in 1969, in which capacity she became one of the ERA’s chief advocates. Her husband, Commander David Bolton U.S.N., later presided over the organization Men for ERA.

With the ERA gaining traction, Roxcy Bolton personally, and successfully, lobbied Indiana Senator Birch Bayh for sponsorship while he was visiting Miami in January 1970. The next month, members of NOW picketed a congressional committee hearing, demanding action on the ERA. On August 10, 1970, U.S. Representative Martha Griffiths of Michigan submitted a petition to finally bring the ERA to the House floor for a debate and vote. It passed and headed to the Senate for approval. On March 22, 1972, the U.S. Senate voted in favor of the ERA.

But the real battle began when the ERA went to the states for ratification, where it would need a three-fourths majority approval to become law. “Our work has just begun,” squared Bolton. “We’ve got to get ratification. We must start in each state and see what we can do.”

Within one year, 30 state legislatures had ratified it. But Florida’s had not. Nonetheless, in 1974, the ERA seemed unstoppable. But eight more states still needed to ratify it by the 1979 deadline and it soon met fierce obstruction.

Roxcy Bolton (center) and Representative Gwendolyn Cherry (to Bolton’s left) leading an ERA march, ca. 1972. Rep. Cherry was the first black woman to serve in the Florida Legislature and the first person to introduce the ERA to the House Judiciary Committee in 1972.

In Florida, the amendment was introduced or voted on in every legislative session from 1972 until 1982. Though it passed the Florida House of Representatives on several occasions, it never passed the Senate. Thirty women served in the Florida legislature between 1920 and 1978, but when the ERA was first introduced into the Florida Senate in 1974, the only woman in the legislative body was Senator Lori Wilson. She became the original sponsor and solitary female voice of the ERA in the senate, and she faced an uphill battle with convincing many of her reluctant colleagues to ratify it. In 1977, she took her stand on the senate floor:

… the good old boys in the southern legislatures traditionally do not consider people issues like ERA on their merit. They consider only what it might do to their manliness or their money-ness or their manpower…. [They]refused to give up their slaves … [or] approve the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote … fought the 1964 Civil Rights Act … until the rest of this nation fought them in the courtrooms, and on the streets, and at the polls … with legal power, and … PEOPLE POWER.

A brochure produced by the American Association of University Women encouraging women to support the Equal Rights Amendment, ca. 1974.

Since its initial submission to the legislature, every Florida governor had expressed support for the ERA.

Governor Reubin Askew addresses an ERA rally on the capitol steps, 1978. Beginning in 1972, Askew also oversaw the first functional Florida Governor’s Commission on the Status of Women, charged with identifying and increasing public awareness of the needs and concerns of Florida women. Among other things, the commission was active in ERA ratification efforts.

But as political scientist Joan S. Carver has observed, the legislature’s unpredictable mix of strong personalities and political interests proved far less agreeable. One of the ERA’s biggest foes was Senator Dempsey Barron of Panama City, who served as Senate President from 1975-76 and in the Senate until 1988. A powerful force in the Florida Senate, Barron emphasized a belief that voting for the ERA would accelerate moral decay and give undue power to the federal government. He asked his senate colleagues, “How many of you want to transfer those remaining powers we have under the present Constitution into the hands of the federal government and the federal courts?” His political sway effectively won several “no” votes during the ERA years.

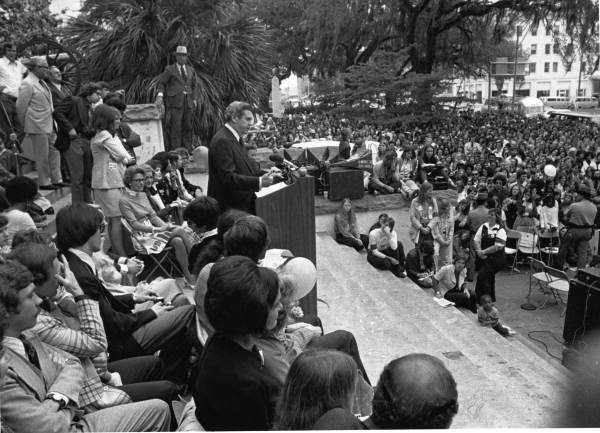

Representative Gene Hodges with lace STOP ERA apron draped from his desk in the House Chamber, 1974. ERA opponents reportedly sported red aprons like this one as they made the rounds at the Capitol, offering baked goods, “from the bread makers to the breadwinners” to legislators. Proponents also began offering up homemade treats. Donn Dughi/State Archives of Florida.

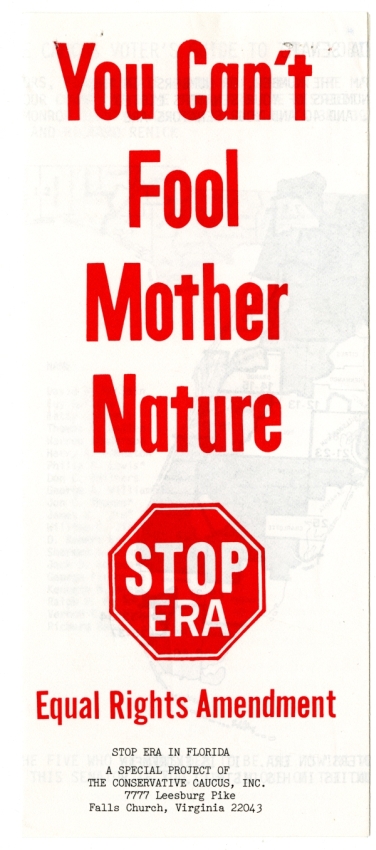

By the mid-1970s, a vocal faction of anti-feminist activists led by lawyer and politician, Phyllis Schlafly, had begun organizing the Stop-ERA campaign. Their strategy was to thwart ratification in the states. “[The ERA] is a giant takeaway of the rights women now have,” Schlafly told a Miami Herald reporter in 1974. “It will not give any advantages to women in the employment area, the one area where women are discriminated against,” she concluded. In Florida, former beauty-queen and anti-gay activist Anita Bryant, along with anti-feminist Miami radio host Shirley Spellerberg, spearheaded Schlafly’s cause. In 1979, Spellerberg explained her belief that women were meant to be homemakers to the Boca-Raton News: “Little girls in the formative years should view women as mothers and homemakers, this is their ideal role in the traditional family structure.” Whereas Florida’s feminists found their political support in the state’s increasingly urban voting base, the Stop-ERA campaign wedged itself into the state’s many conservative, rural and elderly pockets.

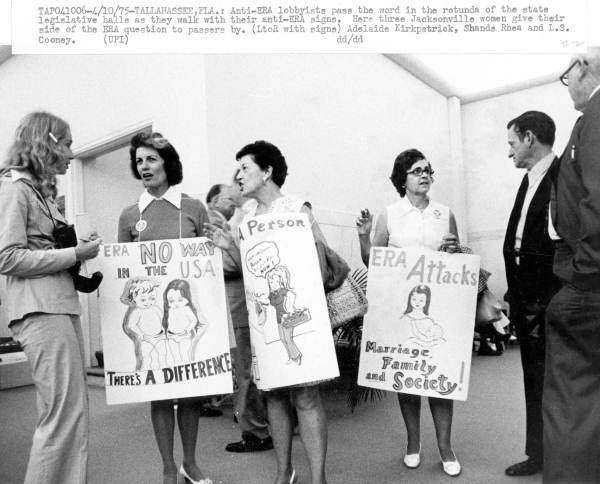

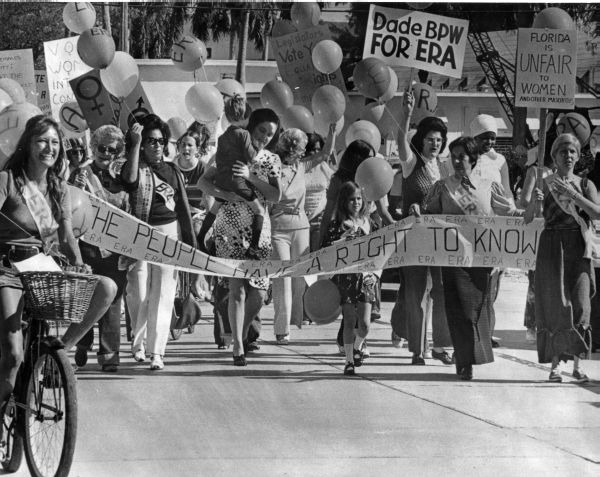

In the 1970s, sizable groups of feminist and anti-feminist activists made regular trips to Tallahassee to lobby the legislature for and against the ERA. Moreover, women from both sides organized rallies, marches, workshops and fundraisers all over the state.

When the original ratification deadline came in 1979, 35 state legislatures had approved the amendment, Florida not included. The ERA was still three states shy of the three-fourths majority needed to amend gender equality to the U.S. Constitution.

Anti-ERA activists line the wall of the Florida Senate Chamber, 1979. State Archives of Florida/Dughi.

In 1978 NOW organized a 100,000 person march in Washington D.C. demanding an extension on the ratification deadline. President Jimmy Carter approved a three year extension. In 1982, four of the remaining 15 undecided states, including Florida, declared special legislative sessions to cast their final vote on the ERA. The state capitol saw tremendous turnout as both pro and anti-ERA activists threw their remaining energy into the last battle over the ERA. The media drew heightened awareness to Florida’s position as a “swing state,” suggesting that the Legislature’s decision on the ERA would be a toss-up.

Constituents from all over the state and nation wrote letters to Governor Bob Graham and their representatives about the matter.

Though it was once poised for quick ratification, the ERA met its final snag with the unpredictable mix of personalities in the Senate, failing in a final vote of 22-16.

Political cartoon showing the final results of the Florida Senate vote on the ERA, 1982. Dana Summers, Orlando Sentinel.

None of the other three legislatures passed it either, and with that, ratification was off the table. Over thirty-five years later, representatives from both the Florida House and Senate have continued to introduce the ERA into committees to no avail. For now, the wildly controversial amendment effectively remains dormant in Florida.

Selected Sources:

Roxcy O’Neal Bolton Papers (M94-1). State Archives of Florida.

Florida Governor’s Commission on the Status of Women (.S 79). State Archives of Florida.

Governor Bob Graham Correspondence Files (.S 850). State Archives of Florida.

***The State Archives of Florida has digitized additional pamphlets and correspondence related to the ratification of the ERA in Florida.

Brock, Laura E. “Religion, Sex, and Politics: The Story of the ERA in Florida.” Florida State University: M.A. Thesis, 2013.

Carver, Joan S. “The Equal Rights Amendment and the Florida Legislature,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 60:4 (April 1982):455-481.

Wilmot Voss, Kimberly. “The Florida Fight for Equality: The Equal Rights Amendment, Senator Lori Wilson and Mediated Catfights in the 1970s,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 88:2(Fall, 2009):173-208.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Florida and the Ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326631.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Florida and the Ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326631. Accessed February 24, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, March 3). Florida and the Ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326631

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program