Description of previous item

Description of next item

When LeRoy Collins Went to Selma

Published March 3, 2017 by Florida Memory

Though he entered office in 1955 as a segregationist, Florida’s 33rd Governor Thomas LeRoy Collins left office in 1961 as an integrationist and never looked back. In 1964, Collins became director of the newly created Community Relations Service (CRS), a federal agency committed to mediating local racial disputes. He traveled to over 100 communities in the mid-1960s, but it was in Selma, Alabama, where the saga of LeRoy Collins, segregationist turned civil rights supporter, peaked. This is his story:

In March 1965, the nation confronted its troubled history of race relations on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Reporters flocked to the small town, their cameras capturing the violent tactics inflicted upon peaceful marchers by local police. The press also managed to snap a seemingly less sensational photo of former Florida Governor LeRoy Collins walking alongside known civil rights leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr and John Lewis.

Photograph of LeRoy Collins talking with civil rights marchers (L-R) John Lewis, Andrew Young, Dr. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Coretta Scott King and Ralph Abernathy at Selma in March 1965.

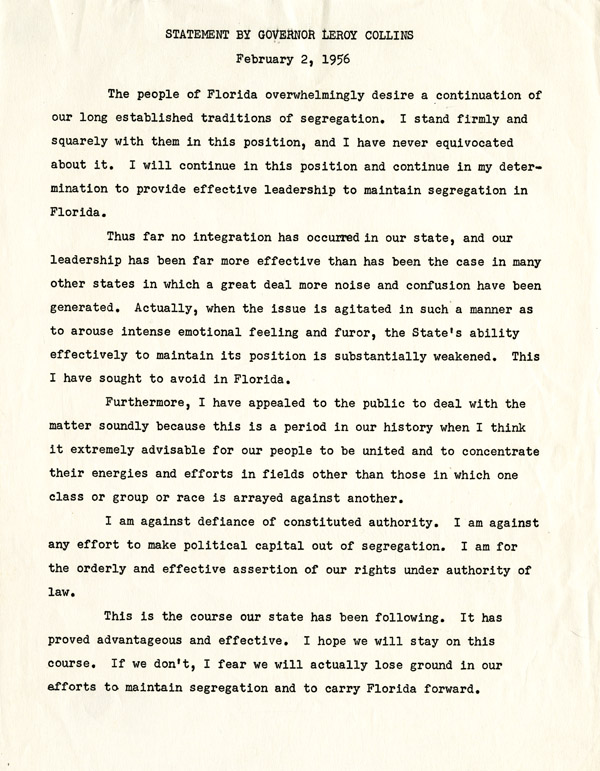

Demanding equal voting rights, King and hundreds of supporters were marching the 50 miles from Selma to the capitol in Montgomery, when Collins briefly joined to confirm the route. However, once the image circulated throughout the country, LeRoy Collins’ legacy became forever linked with the modern civil rights movement. But it also crippled his immediate future as a southern politician. A decade before Selma, Collins, as governor of Florida, defended “separate but equal” as Florida’s “custom and law.” However, as civil rights demonstrations intensified in the late 1950s, Collins’ moderate temperament and commitment to non-violence pushed him to deeply question the morality of segregation.

Born in Tallahassee in 1909, racial segregation was the only way of life young LeRoy Collins knew. “I was raised in the southern tradition of segregation. And like most people in the South I felt that this was all right,” he later reflected. During his first campaign for governor in 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on the case of Brown v. Board of Education, declaring segregated public schools unconstitutional. In contrast to the massive resistance mounted by neighboring southern states, Collins made no immediate comment on the matter and resolved to wait for further instruction from the high court. Instead, his administration remained focused on its original goal of developing Florida’s economy. When he finally spoke on the matter, the governor cited the law, not radical defiance, as the best tool for circumventing desegregation.

Pro-segregation statement issued by Governor LeRoy Collins pledging to maintain segregation in Florida, February 2, 1956. Governor LeRoy Collins Papers (S. 776), box 33, folder 6, State Archives of Florida.

During his second term as governor, Collins began to reconsider his position on segregation. He viewed segregation as more than a simple legal issue, but rather a heavy weight on the southern conscience. Furthermore, while economic advancement had been the cornerstone of his campaign, the statesman soon recognized the correlation between the progress of his home state and the expansion of civil rights.

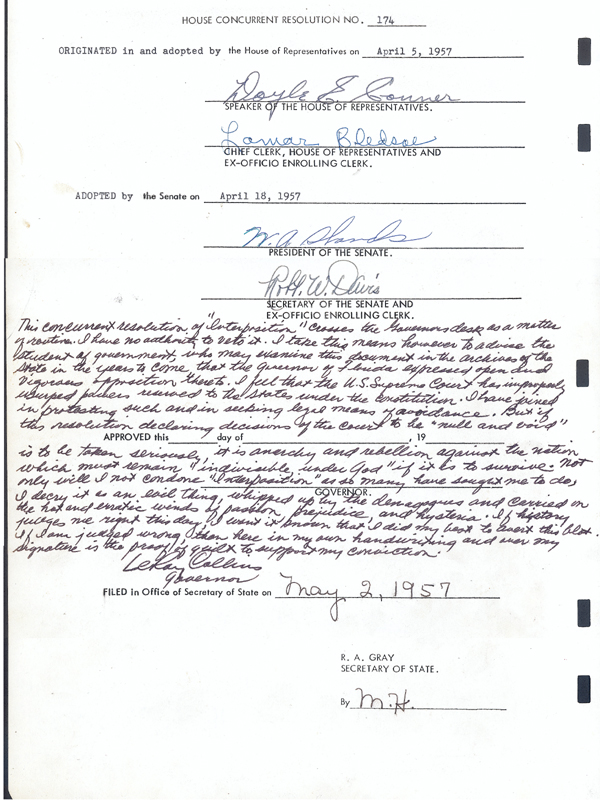

In 1957, the Florida Legislature opposed the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education which required the integration of public schools. The Legislature drafted an “interposition resolution” to declare the Court’s decision as null and void. After the Legislature passed the resolution, Collins had no power to veto it, because it was not a law but only a resolution expressing the opinion of the Legislature on the matter of racial integration.

Collins firmly believed in upholding the foundational institutions of American democracy. Never afraid to speak out against extremism, he openly criticized the 1957 Florida Legislature’s “interposition resolution.” The governor opposed interposition precisely because he felt that defying the Supreme Court amounted to “…anarchy and rebellion against the nation… an evil thing, whipped up by the demagogues and carried on the hot and erratic winds of passion, prejudice, and hysteria.” He concluded his impassioned, hand-written remarks with unwavering dedication to his principles:

“If history judges me right this day, I want it known that I did my best to avert this blot. If I am judged wrong, then here in my own handwriting and over my signature is the proof of guilt to support my conviction.”

LeRoy Collins’ handwritten dissent of the Interposition Resolution, signed May 2, 1957. S. 222, Acts of the Florida Legislature, State Archives of Florida.

Collins’ reaction put him at odds with many white Floridians who sought to protect the status quo, despite strengthened federal civil rights legislation. After denouncing interposition, Collins further revised his position on segregation. The governor’s public response to Tallahassee’s sit-in demonstrations in 1960 revealed the depth of his changed outlook. Amid an atmosphere of heightened racial tensions in Florida’s capital city, the governor appeared before a state-wide audience to address recent events. Collins directly confronted the issue of discrimination at department store lunch counters, a practice he considered “morally wrong” and, although legally permissible, something he could not “square with moral, simple justice.” “We are foolish if we just think about resolving this thing on a legal basis,” he cautioned viewers. As the governor’s remarks continued, he situated the African-American struggle for civil rights within the broader sweep of American history:

“[W]e can never stop Americans from struggling to be free. We can never stop Americans from hoping and praying that someday in some way this ideal that is embedded in our Declaration of Independence is one of these truths that are inevitable that all men are created equal… that somehow will be a reality and not just an illusory distant goal.”

As Florida’s governor, he recognized the rights of opposing sides to demonstrate peacefully but consistently warned against extremism. He called for the creation of bi-racial committees, composed of moderate-minded citizens, who would work to forge solutions at the community level. Above all, he called for a stronger dialogue from southern moderates: “Where are the people in the middle?” he pleaded. “Why aren’t they talking?”

The clarity of conviction voiced by Collins resonated with National Democratic Party leadership, who selected the Tallahassee native as permanent chairman of the convention held in Los Angeles in 1960. Collins masterfully presided over the proceedings which vaulted John F. Kennedy to the presidency. In his opening address captured in the video below, he implored audience members to promptly address the problems afflicting society, saying “ours is a generation in which great decisions can no longer be passed to the next.”

After the convention, the fifty-one-year-old former governor took a job with the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB). Headquartered in Washington, D.C., Collins sought specifically to harness the power of television to further the public interest. Again, he used his position as a seat of moral responsibility, advocating to curb both violence on television and youth-oriented tobacco ads. When President Kennedy was assassinated, Collins again called moderate southerners to action. “It is time the decent people of the south told the bloody shirt wavers to climb down off the buckboards of bigotry,” he told a crowd of white politicians during a 1963 speech in South Carolina. His remarks increasingly distanced the former governor from his native Florida voting base, where many whites still opposed integration. After three years in Washington, the segregationist Governor Collins of 1955 was fading into a memory. By the early 1960s, his views were aligned more closely with Capitol Hill’s than the state Legislature’s.

LeRoy Collins with President Lyndon B. Johnson during the ceremonial signing of the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964

After the passage of Civil Rights Act of 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Collins as Director of the CRS. In this role, Collins was to aid in the enforcement of civil rights legislation in communities across the country in an effort to mediate racial disputes and avoid violent confrontations. Despite the significance of the 1964 law, southern blacks continued to face widespread voter discrimination via literacy tests, voter intimidation and poll taxes. Determined to bring national attention to this reality, Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) selected rural Selma, Alabama as their demonstration site. “Just as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was written in Birmingham, we hope that the new federal voting legislation will be written here in Selma,” explained King. When Dr. King was jailed early on in the Selma campaign, he stressed the specific need for Collins to come down from Washington and speak with local authorities about voting policies. Though he waited for federal direction, it was in his role as CRS director that LeRoy Collins arrived in Selma, Alabama on March 9, 1965. The video below contains footage of the racial climate in Selma during the voting rights demonstrations.

On Sunday, March 7, Alabama state police attacked non-violent protestors who attempted to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge. As federal judges weighed the constitutionality of Alabama Governor George Wallace’s injunction against the march, Collins arrived to represent President Johnson and prevent a repeat of the events of “Bloody Sunday.” In the hours leading up to the second planned march, Collins raced back and forth between SCLC officers and Alabama law enforcement determined to halt marchers’ progress towards Montgomery.

At first, Collins urged Dr. King to call off the march. Dr. King told Collins that he “would rather die on the highway in Alabama than make a butchery of my conscience by compromising with evil.” The civil rights leader added that he could not stop the people from marching, even if he himself did not lead them. According to Dr. King, Collins then presented an alternative plan. The marchers would cross the bridge, face the state police but not attempt to pass their barricade, hold a prayer session near the location of the earlier violence, and then return to their church. Collins then presented his plan to the Alabama troopers. After conferring with Governor Wallace, Sheriff Jim Clark agreed to restrain his forces. Having laid out a scenario acceptable to both sides, Collins assumed a position that would place him directly in between the marchers and the state police. With the march already underway, Collins reassured Dr. King of his intentions:

“I’m going to be standing right there with those troops. It’s not that I’m on their side, but I want to be there so that if some of them moves into you I’ll grab him. I’ll sure personally grab him. I don’t know what I’ll do with him after I get him, but I’ll sure try.”

Dr. King halted the march before the line of state police. They prayed, the troopers parted, and the group, led by Dr. King, returned to the church. Both sides could claim apparent victory. The marchers crossed the bridge and returned unharmed to the scene of Bloody Sunday, and the state police upheld Governor Wallace’s injunction banning the march. President Johnson later told Collins that, if not for his presence in Selma on March 9, “blood would [have] be[en] running knee deep in the ditches.”

Several days later, a federal judge lifted Wallace’s injunction, and the marchers made their way to Montgomery. Along the way to the state capitol, Collins and the CRS stood by to ensure their protection. The third march proceeded in peace, but a photograph taken of Collins next to Dr. King and other members of SCLC immortalized the memory of Collins as a federal representative who supported equal rights.

Collins’ political aspirations suffered greatly as a result of his very public role as mediator during the Selma-Montgomery march. When he ran for U.S. Senate in 1968, his opponents used the photograph of “Liberal LeRoy” walking alongside SCLC leadership as evidence of his pro-civil rights agenda. Many supporters of Collins believe this photograph and the criticism he received as CRS director greatly contributed to his defeat at the polls. In the election, Collins garnered only 48% in his home district of Leon County. Twenty-four years earlier, he was elected governor with 99% of the vote in Leon County, and 80% state-wide.

Below is a clip from a promotional film released during Collins’ 1968 U.S. Senate campaign, highlighting the courage of his actions at Selma:

Many years later, Governor Collins reflected on his decision to stand up for what he believed: “…if I had to do it over again, I would do the same thing… And I would do this even if I knew it would materially influence my defeat for the United States Senate.” The legacy of Governor LeRoy Collins is revealed not only in his commitment to his ideals, but also as an example of an individual who evolved his beliefs in reaction to the changing world around him. After leaving politics, Collins reflected on the consequences of his involvement with the CRS. “Looking back,” he said “I would still accept that job that the President called on me to do and I would have still gone to Selma.”

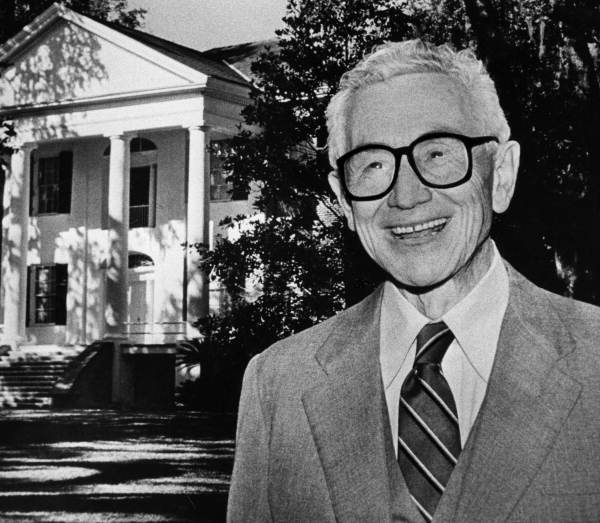

Portrait of LeRoy Collins in front of The Grove, 1985. In 1985, the former governor and his wife, Mary Call Darby Collins, deeded the property to the state, with the express purpose of transforming it into a public museum after both their deaths. LeRoy Collins passed away in 1991 and Mary Call in 2009. Shortly thereafter, the state began its restoration of The Grove.

In March 2017, the Florida Department of State opened The Grove Museum, Governor Collins’ family home in Tallahassee. Built in the 1830s, The Grove was home to two-time territorial governor of Florida, Richard Keith Call, and his descendants. From slavery to civil rights, the exhibits at The Grove Museum cover 200 years of Florida history.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "When LeRoy Collins Went to Selma." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326632.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "When LeRoy Collins Went to Selma." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326632. Accessed March 9, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, March 3). When LeRoy Collins Went to Selma. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326632

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program