Description of previous item

Description of next item

Harry Wesson and J.B. Brown: Justice in Early Twentieth Century Florida

Published February 2, 2017 by Florida Memory

When white railroad engineer Harry E. Wesson was discovered murdered on the morning of October 17, 1901, in the Palatka railyard, Sheriff R.C. Howell faced a public outcry for swift vengeance. The Palatka News & Advertiser described the murder as “the most revoltingly diabolical crime ever committed in Palatka.” Wesson had been ambushed and shot in the back of the head while walking to his home. His pockets had been emptied and his unused pistol lay beside his body.

Sheriff Howell quickly rounded up several black railroad employees who had been working the night of the murder and placed them in the Putnam County jail as suspects. Later that day, a man came to a gap in the jail’s outer fence and asked one of the prisoners to pass a message on to another prisoner. The message was to “Keep your mouth shut and say nothing.” This conversation was overheard by the jailor, and he and the prisoner both identified the messenger as J.B. Brown, a black railroad brakeman. Sheriff Howell was informed of the development and Brown was arrested.

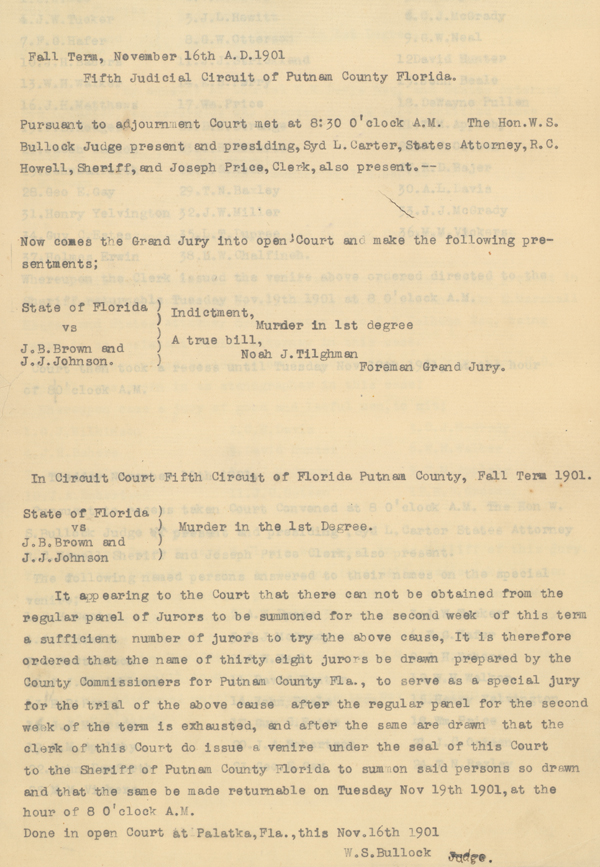

An investigation revealed that Brown had been fired from the railroad after an altercation with a white conductor and that Wesson had intervened on the conductor’s behalf in the conflict. A porter on another train claimed that Brown had threatened to shoot Wesson, and a railroad employee claimed Brown and his friend J.J. Johnson had discussed getting revenge on Wesson prior to the murder. Finally, two prisoners in the jail, Alonzo Mitchel and Henry Davis, came forward and claimed that Brown had confessed to the murder. With a clear motive established and a jailhouse confession, a grand jury was convened and Brown and Johnson were indicted on a charge of murder in the first degree.

The first page of the trial transcript showing the indictment against J.B. Brown and J.J. Johnson on the charge of murder in the first degree (Full trial transcript available in Series 12, Death Warrants, Box 4, Folder 25, State Archives of Florida).

Brown was tried in the circuit court on November 19, 1901, with Judge William S. Bullock presiding. The prosecuting attorneys constructed a compelling circumstantial case against Brown. They argued that Brown had been completely broke on the day before the murder, but had money to gamble hours after the murder. Multiple witnesses testified to the fight with the conductor and Brown’s anger at Wesson for intervening. Most importantly, Mitchel and Davis testified to Brown’s jailhouse confession, even describing details of the crime that they could not have known.

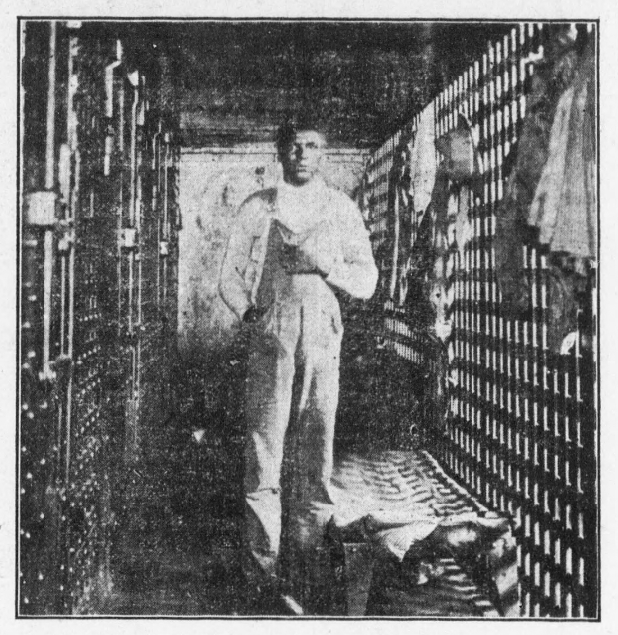

Brown testified on his own behalf. He claimed that while he did have a fight with the conductor, he bore no ill will for Wesson. He claimed to have won the money gambling the night before the murder and to have slept at a friend’s home until after sunrise. The friend testified in support of Brown’s alibi but admitted under cross-examination that he had been asleep when Brown left in the morning. Brown’s defense attorney, John S. Marshall, tried unsuccessfully to show that Mitchel and Davis had been put in his jail cell to extract a confession in exchange for leniency for themselves. The jury retired to consider the evidence and after a short period of deliberation returned a verdict of guilty with no recommendation for mercy. Judge Bullock had no choice but to sentence Brown to death by hanging.

A photograph of J.B. Brown taken in the Putnam County jail for the Palatka News & Advertiser after his conviction for murder (Image credit: University of Florida Digital Collections, Palatka News & Advertiser, January 16, 1902, page 3. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00023798/00005/3j).

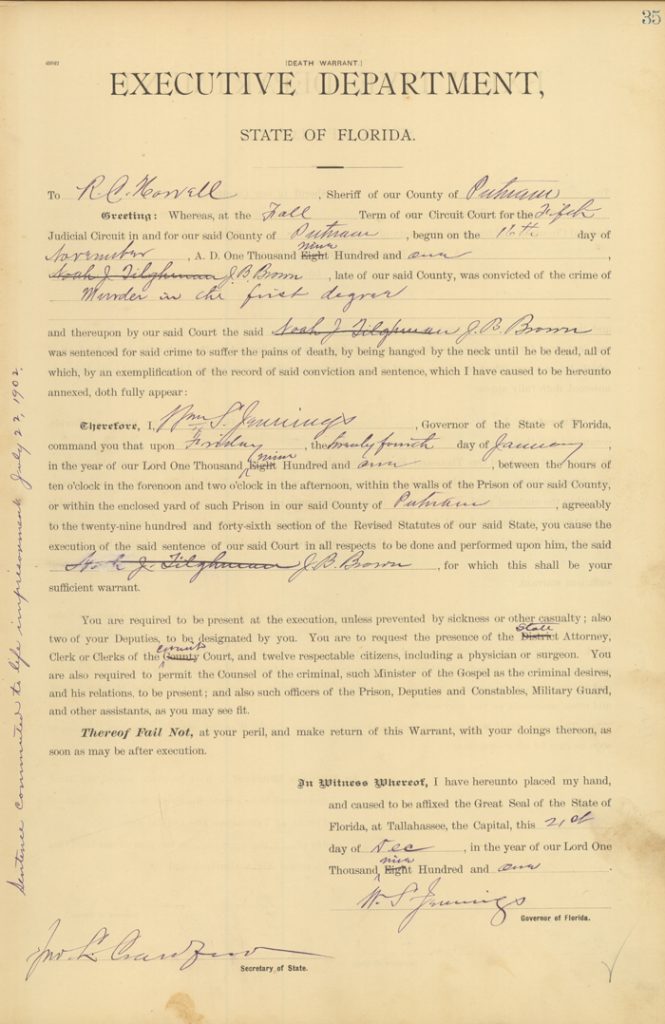

Today, a Florida death row inmate can expect to spend over a decade on death row before being executed, but in the decades prior to the introduction of the electric chair in 1924, hangings were often conducted within days or weeks of the sentencing. Preparations for Brown’s execution were made quickly and a specially built gallows was constructed on the steps of the county courthouse. Governor William S. Jennings signed Brown’s death warrant and sent it to Sheriff Howell. Notices of the pending execution were published in newspapers around the state. There was only one problem: the death warrant called for the execution of the wrong man!

The erroneous death warrant with the name of Noah J. Tilghman crossed out and replaced with J.B. Brown’s name (Series 12, Death Warrants, Box 46, Volume 1: 1896-1923, State Archives of Florida).

Who was Noah J. Tilghman? The Palatka News & Advertiser described him as “one of the most respected of Palatka’s elder citizens.” He was the owner of a local shingle manufacturing company and a Methodist Episcopal preacher. He was also identified on the first page of the trial transcript sent to the governor as the foreman of the grand jury that indicted J.B. Brown. Newspapers around the state published articles asking the governor to make an apology for the inexcusable blunder. This unfortunate clerical error ignited a heated feud between Tilghman and Governor Jennings.

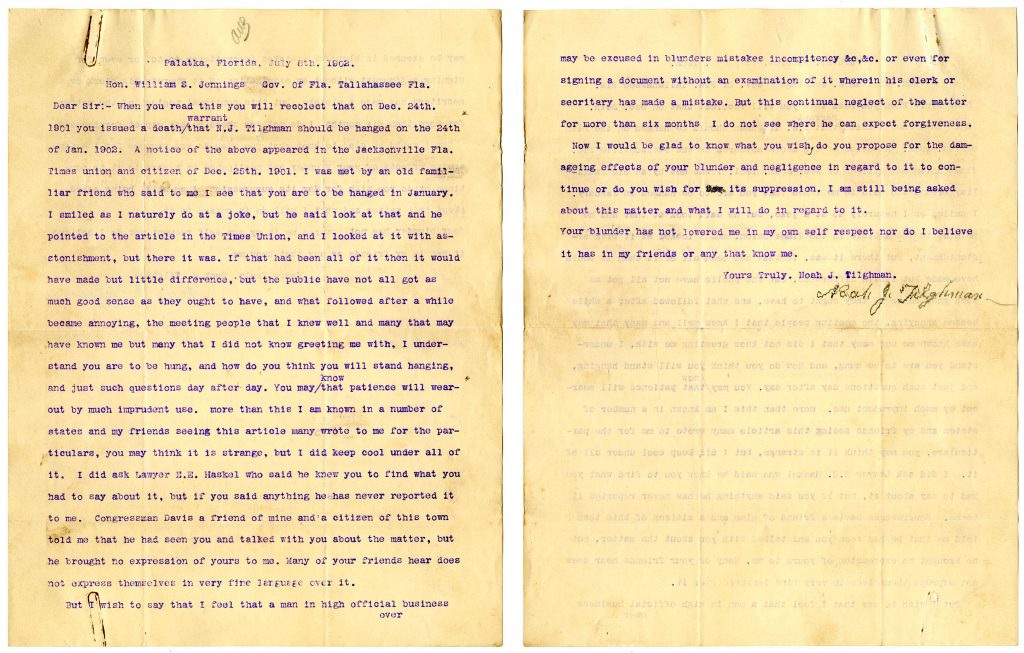

Tilghman wrote to the governor to express his willingness to forgive the blunder if he received an apology for the embarrassment he had experienced. He wrote of discovering the error when a close friend had remarked to him: “I see that you are to be hanged in January.” After that time, he had been the butt of constant jokes and received many concerned letters from distant relatives.

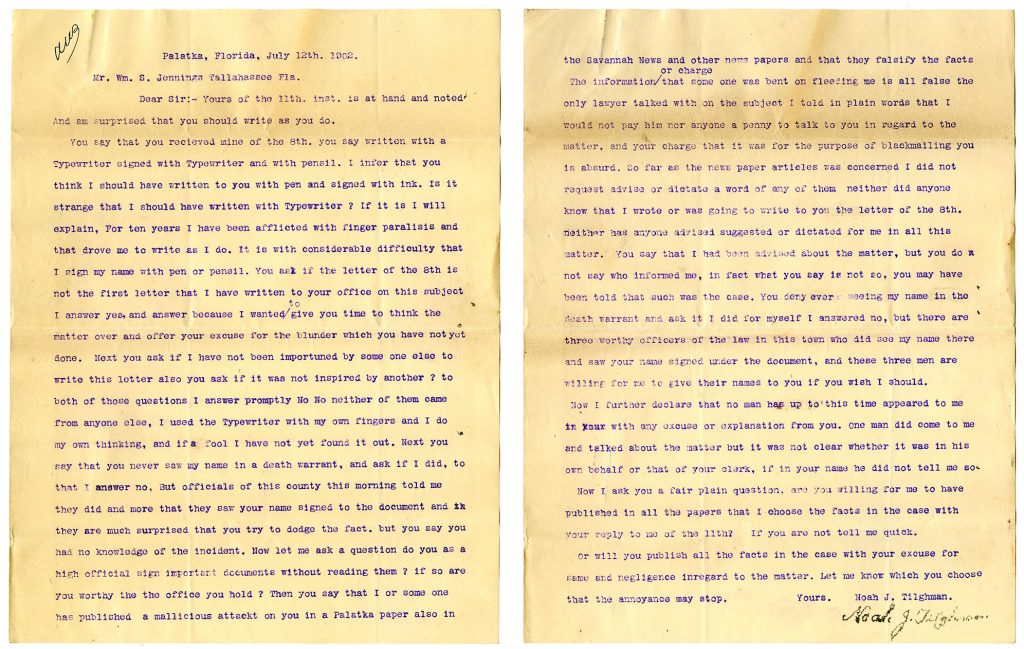

The first of many letters sent by Noah J. Tilghman to Governor William S. Jennings (Letters found in Governor Jennings Correspondence 1901-1904, Series 596, Box 9, Folder 3, Florida State Archives).

Jennings, however, would not apologize and even denied that the faulty warrant existed despite multiple witnesses having seen it. This led Tilghman to question the governor’s competence by asking “do you as a high official sign important documents without reading them? [I]f so are you worthy of the office you hold?” In fact, his initial response to Tilghman’s letter was so offensive that Tilghman angrily threatened to publish it in the newspapers. The two exchanged hostile letters over the next months, but Jennings never apologized for his blunder.

Noah J. Tilghman’s letter in response to Governor William S. Jennings’ offensive reply to his first letter (Series 596, Box 9, Folder 3, State Archives of Florida).

Meanwhile, the erroneous death warrant was corrected and plans for J.B. Brown’s execution resumed. However, days before the scheduled execution, Governor Jennings annulled the death warrant to allow Brown’s Florida Supreme Court appeal to be heard, angering many. Reflecting the sentiment in Palatka at the time, the Palatka News & Advertiser stated that “Brown is a worthless negro. Guilty or not the town would be better off rid of him and his ilk.”

Marshall argued to the Supreme Court that the alleged jailhouse confession was fraudulent and without it Brown’s guilt could not be established. In its decision, the Supreme Court wrote that “There is very little testimony to connect the defendant with the crime aside from his extra judicial confession” but upheld the jury’s decision. Brown once again faced the gallows.

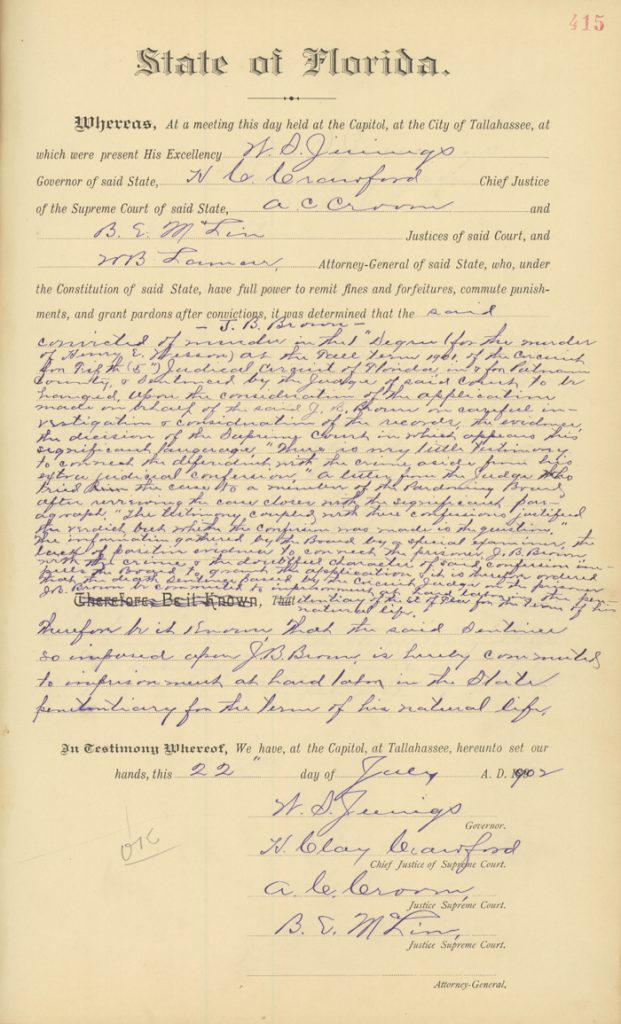

Brown’s only hope was for a reprieve from the state board of pardons. Judge Bullock wrote to the governor that he believed there was enough evidence to convict Brown, but that he also had misgivings about the alleged confession. Benjamin P. Calhoun, one of the prosecutors, had no such misgivings. He wrote that “the entire white population, except republicans, are absolutely convinced of the guilt of the accused,” and that “Brown is guilty beyond question, and should suffer the death penalty.” The board of pardons, citing the concerns over the legitimacy of the confession, commuted Brown’s sentence to life in prison on July 22, 1902.

J.B. Brown’s commutation of sentence decree from the state board of pardons (Series 158, Pardon, Commutation, and Remission Decrees, 1869-1909, Volume 2, State Archives of Florida).

While J.B. Brown was spared execution, he still faced life imprisonment in Florida’s notoriously brutal convict-lease prison system. In the early twentieth century, nearly all state prisoners were leased to private companies for hard labor in often deplorable conditions. Prisoners were expected to labor from sunup to sundown mining phosphate or turpentine, clearing swamps, harvesting timber, or building roads. Guards subjected them to brutal punishments including whipping, solitary confinement in sweat boxes, and even torture. Deaths were not uncommon.

Brown appeared destined to spend the rest of his life in prison until J.J. Johnson, who had not been tried for the murder, confessed to the crime on his deathbed and exonerated Brown in early 1913. By then, J.B. Brown had served nearly twelve years at hard labor for a crime he did not commit. This new confession convinced the board of pardons to grant Brown a conditional pardon releasing him from prison effective October 10, 1913. When he was released, he suffered from physical disabilities caused by his years at hard labor, and it wasn’t until 1929 that the “aged, infirm, and destitute” Brown received a pension of $2,492 from the Legislature as compensation for this miscarriage of justice.

J.B. Brown’s story was discovered in Series S500, Prisoner Registers, 1875-1972, an ongoing digitization project at the State Archives of Florida for Florida Memory. Stay tuned for updates regarding the online release of these digitized records. Information was also obtained from the University of Florida Digital Collections holdings of the Palatka News & Advertiser found here. Of particular interest in writing this blog were the issues from January 16, 1902 and February 6, 1902.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Harry Wesson and J.B. Brown: Justice in Early Twentieth Century Florida." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326635.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Harry Wesson and J.B. Brown: Justice in Early Twentieth Century Florida." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326635. Accessed February 24, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, February 2). Harry Wesson and J.B. Brown: Justice in Early Twentieth Century Florida. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326635

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program