Description of previous item

Description of next item

The History of Stanton High School

Published February 2, 2017 by Florida Memory

Once heralded by the Florida Times-Union as the “crown jewel of Jacksonville’s public schools,” Stanton College Preparatory School’s nationally recognized academic magnet program has attracted widespread publicity since the Duval County School Board first implemented the curriculum in the early 1980s. In 2016, U.S. News and World Report ranked Stanton fifth out of Florida’s 889 public high schools and 33rd out of all public schools in the nation. But Stanton’s roots as an exceptional scholastic institution stretch back much further than the inception of the magnet program. For nearly a century, from Reconstruction until school desegregation orders came in the 1950s, Stanton High School operated one of the most well-regarded secondary schools for African-American students in Florida.

Named after Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Stanton Institute, which later became known as Stanton High School, opened in 1868 as the first and only public secondary school for African-Americans in Reconstruction Florida. There were approximately 62,000 newly emancipated slaves living in Florida, and many of them flocked to Jacksonville looking for job opportunities and cheap land in the port city. Eager to start their own communities after emancipation, local blacks built churches, schools, social organizations and businesses. The Colored Education Society of Jacksonville formed out of these grassroots efforts. At the same time, both the American Missionary Association (AMA), a northern benevolent aid society, and the federally funded Freedmen’s Bureau established a presence in northeast Florida. The three entities worked together to support the establishment and staffing of schools for blacks.

Pamphlet advertising land for sale in Jacksonville and the services offered by the Freedman’s Savings Bank, 1867. During Reconstruction, both the Freedman’s Savings Bank and the American Missionary Association set up headquarters offices in Jacksonville.

In 1866, the Florida Legislature sought to abate white anxieties over educated blacks and passed a law requiring the establishment of separate schools for blacks and whites. At that time, three schools for Jacksonville’s freedmen and women existed, but they employed only a total of four teachers responsible for the instruction of a total of 530 pupils. In response to the shortage of qualified black teachers, the Colored Education Society of Jacksonville and local black freeholders raised $850 to purchase a large plot of land on Beaver Street, from white unionist and future Florida governor Ossian B. Hart, and his wife, Catherine. The Harts endowed the black community with a 99-year lease, specifying the plot be used for the express purpose of educating blacks and training them as teachers.

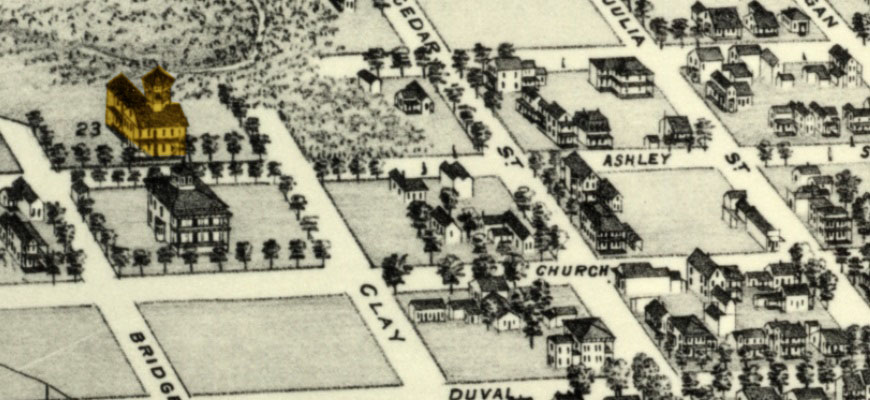

Unfortunately, no additional capital was available for the immediate construction of a training school. The Freedman’s Bureau donated $16,000 to build Stanton Institute with the purpose of training African-American women from the ages of 16 to 25 as educators. The Freedmen’s Bureau erected the Stanton Institute on the corner of Ashley and Bridge (later Broad) streets in December 1868, and officially opened it for use on April 10, 1869. In addition to operating a teacher training program, the new building also facilitated a grammar school. The first class at Stanton was comprised of 348 black students, six white teachers and a number of black staff.

Excerpt from an 1876 bird’s-eye view map of Jacksonville, with Stanton highlighted in gold on the corner of Ashley and Bridge streets. State Library of Florida map collection. Note: Archives staff highlighted the location for emphasis, the original map is monochromatic.

When Reconstruction ended in 1877, the presence of northern aid societies quickly diminished in Florida, and the financing of public education for African-Americans came under control of local school boards. The Duval County School Board first listed Stanton as a public school in 1882. Once staffed by a majority of white teachers, black educators made up the entirety of Stanton faculty by the 1880s; they worked to upgrade the curriculum to meet new state standards. Even in its infancy, reviewers touted Stanton as the “best school for blacks in the state.” The news about the black educational marvel in Jacksonville extended across state lines, as the site developed into a popular destination for late nineteenth century tourists.

Stereo print of Stanton Institute, ca. 1880. This print is one half of a stereograph, produced by photographer Charles Seaver in the late 19th century as part of a series he did on southern attractions. When viewed through a stereo viewer, the image appears three-dimensional. Stereography was a popular method for sharing images of notable scenes and sites. It is likely that people living outside of Florida saw this image of Stanton as an example of a school for African-Americans in the South.

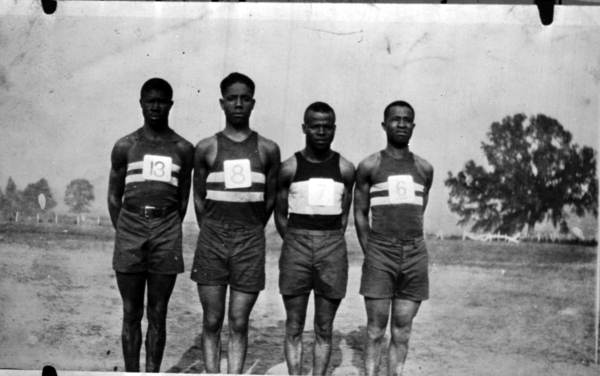

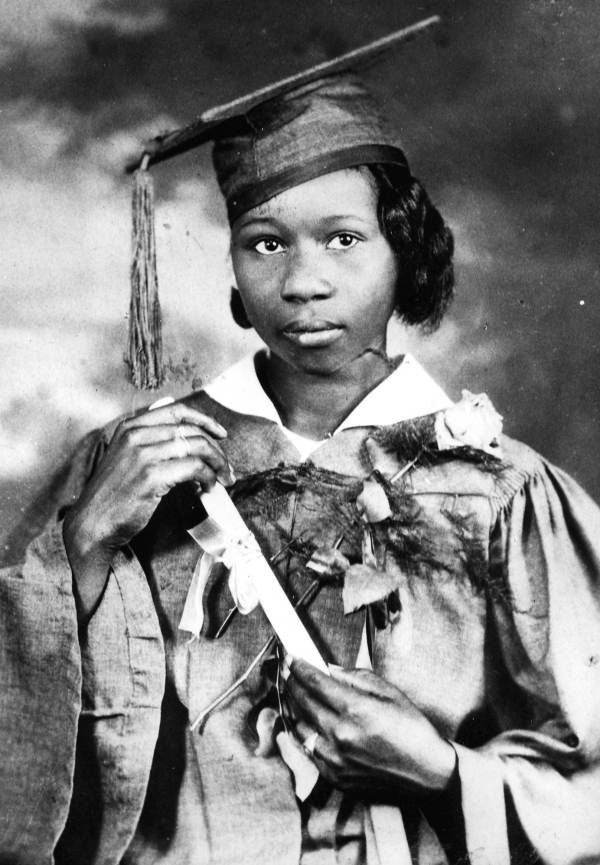

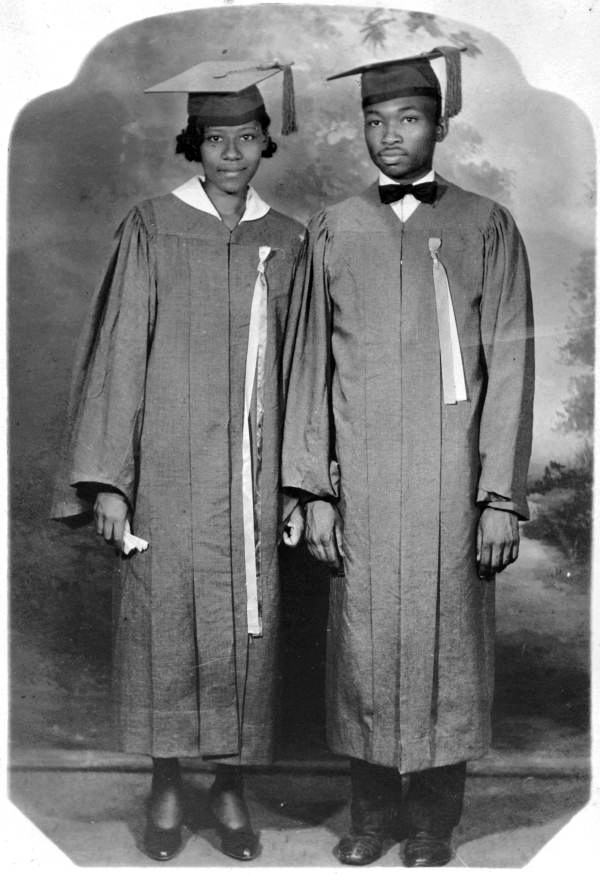

Principal James Weldon Johnson, a Stanton alumnus and the first African-American to serve as Executive Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, elevated Stanton to a high school level in the 1890s. For a number of years Stanton was the only secondary school for African-Americans in Jacksonville, and one of the few in the state. By 1900, a reported 73 percent of local blacks could read and write. Other notable Stanton alumni include journalist T. Thomas Fortune, Olympic long-jumper Edward “Ned” Orval Gourdin and Jacksonville philanthropist Eartha M.M. White.

Portrait of Principal James Weldon Johnson, ca. 1900. Johnson served as principal of Stanton from 1894 until 1902. Johnson’s mother, Helen Dillet Johnson, was one of the first black teachers in the state and taught at Stanton for two decades. Both of her sons, James Weldon and John Rosamond, completed eight grade educations at Stanton in the 1880s. After furthering his education at Atlanta University, James Weldon Johnson returned to Jacksonville and took the job as principal of Stanton. During this time, he established the Daily American, a short-lived newspaper dedicated to covering black life. Additionally, he became the first African-American admitted to the Florida Bar since Reconstruction. After school board officials denied Johnson’s request for a pay increase comparable to white salaries, he resigned and relocated to New York City.

The second Stanton Institute building, 1897. A fire twice destroyed the school, once in 1882 and again in 1901. Property insurance paid to rebuild the school after both incidents.

A consistent lack of maintenance funding from the county school board plunged Stanton into physical disrepair by the early 20th century. Stanton’s trustees filed suit against the Duval County Schools (Floyd v. Board of Public Instruction, 1915), alleging the unacceptable conditions of the school. Officials agreed to construct a new brick building in its place, but again refused to allocate proper funds for building maintenance. By the 1920s, the new Stanton building was already deteriorating.

This negligence reflected general trends afflicting black education in Florida during Jim Crow. As of 1942, Duval County operated a total of 42 schools for African-Americans, but only one of those, Stanton, offered courses at the high school level. Beginning in 1938, Stanton stopped offering all grade levels and taught secondary education students only. Nearly every black school in the district suffered from a disparate level of resources. For example, in 1946, the annual per capita expenditure of $70.24 at black high schools in Duval County could not compete with the $104.50 spent on each white student pursuing a secondary education. Out of the 95 black teachers in the county holding at least a bachelor’s degree, 91 received a monthly salary of $189, while whites with the same credentials received an average $233 per month in 1946.

After two decades of petitioning the Duval County School Board for an updated African-American high school plant, officials finally obliged. On November 24, 1953, student, faculty and interested locals dedicated the new $1.5 million Stanton High School. The previous structure on Broad and Ashley became known as Old Stanton, and the new high school, New Stanton. The new school was equipped to educate a maximum of 1,500 pupils on a 24-acre plot located at 1149 W. 13th Street. After the high school’s student body relocated, the school board converted the old Stanton building first into a middle school, and then into the designated black vocational school, until 1971, when officials condemned the dilapidated structure. In the 1990s, the structure reopened as a private school called the Academy of Excellence.

A year after the new Stanton building opened, rumblings on the national level began to steer the school in a new direction. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled segregated schools unconstitutional (Brown v. Board of Education). The judicial body later ordered segregated school districts to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” The vague implementation language allowed southern school boards to delay integration for over a decade. In the video clip below, Florida Attorney General Richard Ervin and State Superintendent of Public Instruction Thomas Bailey discuss some of the tactics used to circumvent the order.

During this time, life at Stanton carried on much as it had before the landmark legal ruling. Overcrowding forced students to attend classes in shifts and a lack of resources handicapped instruction. Despite these shortcomings, Stanton students and faculty took great pride in their school. In 1959, Jacksonville’s black newspaper, The Florida Star named Stanton “the best landscaped school in the city.” In 1961, New Stanton’s yearbook and newspaper staff won multiple awards at the 11th Annual Intercollegiate Press Workshop held at Florida A&M University.

Faculty also made certain to instill strong character in their students. Alumnus Rudolph Daniels recalled Principal Brooks’ infamously stern demeanor: “If it was time to be in class, they’d better be in class. It if it was time for sports or activities, they should be involved in those. He wanted students to be equally involved in different things to make them well rounded people.” During Brooks’ tenure the school flourished as an asset and centerpiece of Jacksonville’s middle-class black community. “Almost every Black [sic] who is in business in this city finished under me,” concluded the retired educator.

Students from New Stanton High School performing at the Florida Folklife Festival in White Springs, 1956.

Though Jacksonville’s black parents sued Duval County School Board for refusal to integrate local schools (Braxton vs. Duval County, 1960), meaningful racial integration did not commence until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title VI of the federal legislation empowered the Department of Health Education and Welfare to withhold funding from those districts non-compliant with integration orders. Florida lawmakers responded. The following school year, all 67 counties in the Sunshine State adopted plans for integration, including Duval. Later Supreme Court rulings in Green vs. New Kent County (1968) and Alexander v. Holmes County (1969) placed additional pressure on local school boards to integrate immediately and dismantle segregated school systems “root and branch.” A federal judge ordered all student, faculty and staff fully integrated by Feb 1, 1970.

Mrs. Pearson picks up her youngest daughter from the newly integrated Fulford Elementary School in Miami, September 6, 1960. In 1959 Dade County became the first Florida school district to integrate black and whites students. Other districts, such as Duval, opposed such action until the mid to late 1960s.

While Jacksonville schools officially achieved a unified school district by federal standards in the early 1970s, the majority of schools, including Stanton, remained racially divided. In the post-desegregation era, Stanton’s identity as an outstanding community school began to change. The school board converted it into a vocational school in 1971. Principal Charles D. Brooks left the school in 1968, but went on to characterize Stanton after 1971 in telling detail: “It seemed that one objective of the school board was to keep white students out of Stanton. We integrated with them, but they didn’t integrate with us.” Just as before Brown, African-American pupils at Stanton still suffered from the legacy of Jim Crow. Throughout the 1970s, New Stanton’s student body faced a new battle with poor performance. A 1977 report of standardized test scores ranked Stanton with the lowest pass rates in Duval County for both math and reading. Further, the school reported the highest dropout rate in the district.

Though fortunate to survive the consolidation process of school desegregation in the 1960s–school boards routinely closed black high schools to meet integration standards–Stanton’s reputation as the best school for blacks in Florida waned in the 1970s. Once plagued by overcrowding, by 1980 the one hundred percent black school filled only one third of its capacity; the school board had anticipated the matriculation of hundreds of white students after integration, but none chose to enroll at Stanton. Board officials even considered closing the plant, just as they had done with the Old Stanton building ten years earlier.

Desperate to preserve Stanton as a piece of Jacksonville’s history, the black community rallied to save the school. The school board appointed Stanton graduate and University of North Florida professor, Dr. Andrew Robinson to find a solution for revitalizing and integrating the school. Duval County ultimately chose to tap resources from the Emergency School Aid Act (ESAA), the federal government’s primary source for funding school desegregation efforts. In an effort to attract a more diverse mix of students, the school reopened as Stanton College Preparatory School in 1981 and began offering a magnet program with a focus on academic excellence.

Thirty-five years later, however, the effectiveness of the magnet program in achieving racial integration remains questionable. According to the most recent data compiled by the Florida Department of Education, Stanton’s student body is 48 percent white and only 17.7 percent black, but blacks comprise 44 percent of Duval County’s total student population. Moreover, only 13.2 percent of Stanton students are economically disadvantaged, whereas 43.8 percent of pupils living in the district come from low-income households.

From 2000-2003 Newsweek rated Stanton as the number one public school in the United States, and it continues to enjoy an outstanding reputation. For all of Stanton’s modern achievements, though, current students and faculty are careful to remember the school’s important place in the history of African-American education in Florida.

Selected Sources:

Stanton High School Collection. Jacksonville: Jacksonville Public Library Special Collections.

Eartha M.M. White Papers. Jacksonville: University of North Florida Special Collections.

Bartley, Abel A. Keeping the Faith: Race, Politics, and Social Development in Jacksonville, Florida, 1940-1970. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Florida Times-Union

Florida Star

Florida Department of Education

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "The History of Stanton High School." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326636.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "The History of Stanton High School." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326636. Accessed February 24, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, February 2). The History of Stanton High School. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/326636

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program