Transcript

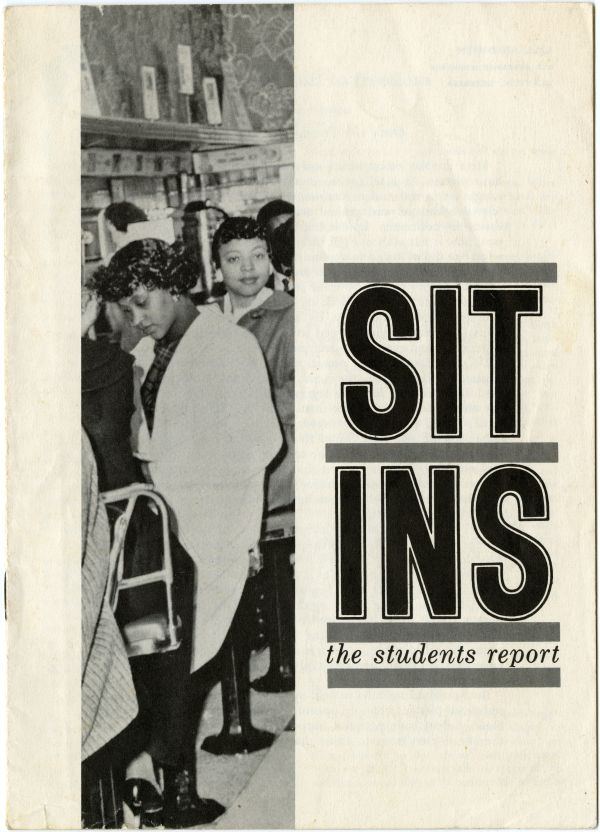

SIT

INS

the student report

LILLIAN SMITH

OLD SCREAMER MOUNTAIN

CLAYTON, GEORGIA

Only the Young and the Brave

Here are six letters which only the young and the brave could have written. Each tells with simplicity and grace how it felt to be caught up in the students' movement of nonviolent protest: how it felt to be beaten and pushed around by hoodlums and, in some towns, by policemen; how it felt to be hustled off to jail and bull pen; how it felt after one got there; and how it now feels to analyze what one did or failed to do, and what one must do, next time. For there will be "next times": you are sure of it as you read.

I was deeply moved by these stories. There is validity in them; and thoughtfulness, and modesty, and a nice understatement. But courage shines through - as do high spirits and gaiety and refusal to resent which turned some nasty ordeals into significant experience, and even into adventure.

Do not misunderstand, please, my use of "adventure." These students are highhearted, they can laugh, thank God, at the crazy, mad absurdities of life in a segregated culture; they can shrug off the obscenities; and I honor them for it. But they are serious, they have suffered and will suffer again; they have made grave, enduring commitments and have found the courage to risk; but none of it has been easy. Nor should it be easy for us to accept their sacrifice and suffering. Let's not forget that these students are going to jail not only for their freedom but for yours and mine; not only because they have been hurt by the indignities of segregation but because we all have been hurt.

As I watch them, as I see the movement spread from college to college and city to city, I am deeply stirred as are millions of other Americans. What is it we feel? What do we hope for? I can answer only for myself: For me, it is as if the No Exit sign is about to come down from our age. It is the beginning of new things, of a new kind of leadership. If the white students will join in ever-increasing numbers with these Negro students, change will come; their experience of suffering and working together for what they know is right; the self-discipline, the refusal to act in violence or think in violence will bring a new spiritual life not only to our region but to our entire country.

But you and I must help: first, by understanding what non-violent resistance means, what its possibilities are; and second, by giving these students our personal support. They need money, yes; but they need even more to know that we are with them.

Lillian Smith

tallahassee: through jail to freedom

by Patricia Stephens Florida A & M

I am writing this in Leon County Jail. My sister Priscilla and I, five other A & M students and one high school student are serving 60-day sentences for our participation in the sit-ins. We could be out on appeal but we all strongly believe that Martin Luther King was right when he said: "We've got to fill the jails in order to win our equal rights." Priscilla and I both explained this to our parents when they visited us the other day. Priscilla is supposed to be on a special diet and mother was worried about her. We did our best to dispel her worries. We made it clear that we want to serve-out our full time.

Students who saw the inside of the county jail before I did and were released on bond, reported that conditions were miserable. They did not exaggerate. It is dank and cold. We are in what is called a "bull tank" with four cells. Each cell has four bunks, a commode and a small sink. Some of the cells have running water, but ours does not. Breakfast, if you can call it that, is served at 6:30. Another meal is served at 12:30 and in the evening, "sweet" bread and watery coffee. At first I found it difficult to eat this food. Two ministers visit us every day. Sundays and Wednesdays are regular visiting days, but our white visitors who came at first are no longer permitted by the authorities.

There is plenty of time to think in jail and I sometimes review in my mind the events which brought me here. It is almost six months since Priscilla and I were first introduced to CORE at a workshop in Miami. Upon our return we helped to establish a Tallahassee CORE group, whose initial meeting took place last October. Among our first projects was a test sit-in at Sears and McCrory's. So, we were not totally unprepared when the south-wide protest movement started in early February.

Our first action in Tallahassee was on Feb. 13th. At 11 a.m. we sat down at the Woolworth lunch counter. When the waitress approached, Charles Steele, who was next to me, ordered a slice of cake for each of us. She said: "I'm sorry: I can't serve you" and moved on down the counter repeating this to the other participants. We all said we would wait, took out our books and started reading—or at least, we tried.

The regular customers continued to eat. When one man finished, the waitress said: "Thank you for staying and eating in all this indecency." The man replied: "What did you expect me to do? I paid for it."

One man stopped behind Bill Carpenter briefly and said: "I think you're doing a fine job: just sit right there." A young white hoodlum then came up behind Bill and tried to bait him into an argument. Unsuccessful, he boasted to his friends: "I bet if I disjoint him, he'll talk." When Bill didn't respond, he moved on. A number of tough looking characters wandered into the store. In most instances the waitress spotted them and had them leave. When a few of them started making derisive comments, the waitress said, about us: "You can see they aren't here to start anything." Although the counters were closed 20 minutes after our arrival, we stayed until 2 p.m.

The second sit-in at Woolworth's occurred a week later. The waitress saw us sitting down and said: "Oh Lord, here they come again!" This time a few white persons were participating, secretly. They simply sat and continued eating, without comment. The idea was to demonstrate the reality of eating together without coercion, contamination or cohabitation. Everything was peaceful. We read. I was reading the "Blue Book of Crime" and Barbara Broxton, "How to Tell the Different Kinds of Fingerprints"—which gave us a laugh in light of the arrests which followed.

At about 3:30 p.m. a squad of policemen led by a man in civilian clothes entered the store. Someone directed him to Priscilla, who had been chosen our spokesman for this sit-in. "As Mayor of Tallahassee, I am asking you to leave," said the man in civilian clothes.

"If we don't leave, would we be committing a crime?" Priscilla asked. The mayor simply repeated his original statement. Then he came over to me, pointed to the "closed" sign and asked: "Can you read?" I advised him to direct all his comments to our elected spokesman. He looked as

though his official vanity was wounded but turned to Priscilla. We did too, reiterating our determination to stay. He ordered our arrest. Two policemen "escorted" each of the eleven of us to the station. I use quotes because their handling of us was not exactly gentle nor were their remarks courteous. At 4:45 we entered the police station. Until recently the building had housed a savings and loan company, so I was not surprised to observe that our cell was a renovated bank vault. One by one, we were fingerprinted.

After about two hours, the charges against us were read and one of us was allowed to make a phone call. I started to call Rev. C. K. Steele, a leader of nonviolent action in Tallahassee whose two sons were involved in the sit-ins. A policeman stopped me on the grounds that Rev. Steele is not a bondsman. I heard a number of policemen refer to us as "niggers" and say we should stay on the campus.

Shortly, the police captain came into our cell and announced that someone was coming to get us out. An hour later we were released—through the back door, so that the waiting reporters and TV men would not see us and give us publicity.

However, the reporters were quick to catch on and they circled the building to meet us.

We were arraigned February 22 and charged with disturbing the peace by riotous conduct and unlawful assembly. We all pleaded "not guilty!" The trial was set for March 3. A week prior to that date the entire A & M student body met and decided to suspend classes on March 3 and attend the trial. The prospect of having 3000 students converge on the small courtroom was a factor, we believe, in causing a 2-week postponement. Our biggest single demonstration took place on March 12 at 9 a.m. The plan was for FSU students, who are white, to enter the two stores first and order food. A & M students would arrive later and, if refused service, would share the food which the white students had ordered. It was decided that I should be an observer this time rather than a participant because of my previous arrest.

The white and Negro students were sitting peacefully at the counter when the mayor and his corps arrived. As on the previous occasion, he asked the group to leave, but when a few rose to comply, he immediately arrested them. As a symbolic gesture of contempt, they were marched to the station in interracial pairs.

After the arrests many of us stood in a park opposite the station. We were refused permission to visit those arrested. I rushed back to report this on campus. When I returned to the station, some 200 students were with me. Barbara Cooper and I, again, asked to visit those arrested. Again, we were refused.

Thereupon, we formed two groups and headed for the variety stores. The 17 who went to McCrory's were promptly arrested. The group headed for Woolworth's was met by a band of white hoodlums armed with bats, sticks, knives and other weapons. They were followed by police. To avoid what seemed certain violence, the group called off the sit-in at Woolworth's and returned to the campus in an orderly manner.

We asked the president of the student body to mobilize the students for a peaceful march downtown. He agreed but first tried, without success, to arrange a conference with the mayor.

However, the mayor was not too busy to direct the city, county and state police who met us as we neared the downtown area. There were 1000 of us, in groups of 75—each with two leaders. Our hastily printed posters said: "Give Us Our Students Back," "We Will Not Fight Mobs," "No Violence," "We Want Our Rights: We are Americans, Too."

As we reached the police line-up, the mayor stepped forward and ordered us to disperse within three minutes. But the police did not wait: they started shooting tear gas bombs at once. One policeman, turning on me, explained: "I want you!" and thereupon aimed one of the bombs directly at me. The students moved back toward campus. Several girls were taken to the university hospital to be treated for burns. Six students were arrested, bringing the total arrests for the day to 35. Bond was set at $500 each and within two days all were out.

The 11 of us arrested on February 20 were tried on March 17. There was no second postponement. The trial started promptly at 9:30. Five additional charges had been made against us, but were subsequently dropped. During the trial, Judge Rudd tried to keep race out of the case. He said it was not a factor in our arrest. But we realize it was the sole factor. The mayor in his testimony used the word "nigger" freely. We were convicted and sentenced to 60-days in jail or a $300 fine. All 11 had agreed to go to jail but three paid fines upon advice of our attorneys.

So, here I am serving a 60-day sentence along with seven other CORE members. When I get out, I plan to carry on this struggle. I feel I shall be ready to go to jail again if necessary.

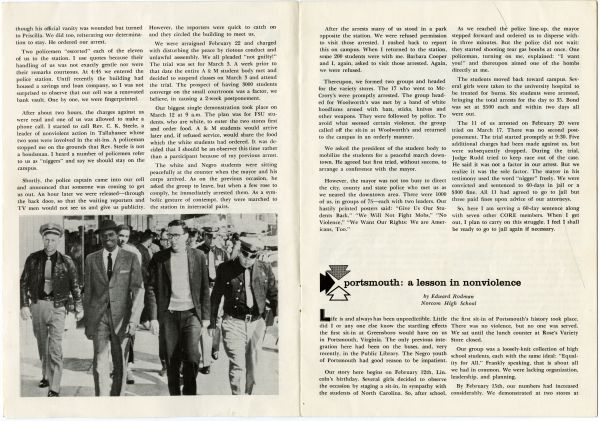

portsmouth: a lesson in nonviolence

by Edward Rodman

Norcom High School

Life is and always has been unpredictable. Little did I or anyone else know the startling effects the first sit-in at Greensboro would have on us in Portsmouth, Virginia. The only previous integration here had been on the buses, and, very recently, in the Public Library. The Negro youth of Portsmouth had good reason to be impatient.

Our Story begins on February 12th, Lincoln's birthday. Several girls decided to observe the occasion by staging a sit-in, in sympathy with the students of North Carolina. So, after school, the first sit-in of Portsmouth's history took place. There was no violence, but no one was served. We sat until the lunch counter at Roses's Variety Store closed.

Our group was a loosely-knit collection of high school students, each with the same ideal: "Equality for All." Frankly speaking, that is about all we had in common. We were lacking organization, leadership, and planning.

By February 15th, our numbers had increased considerably. We demonstrated at two stores at

the Shopping Center. Again we met no obstruction -only a few hecklers, worst insults we passed off with a smile. Things were looking good. The newspaper and radio reporters were there getting our story.

Our spontaneous movement was gaining momentum quickly. We were without organization; we had no leader and no rules for conduct other than a vague understanding that we were not to fight back. We should have known the consequences, but we didn't.

I was late getting to the stores the following day, because of a meeting. It was almost 4:00 p.m. when I arrived. What I saw will stay in my memory for long time. Instead of the peaceful, non-violent sit-ins of the past few days. I saw before me a swelling, pushing mob of white and Negro students, news-photographers, T.V. cameras and only two policemen. Immediately, I tried to take the situation in hand. I did not know it at the time, but this day I became the sit-in leader.

I didn't waste time asking the obvious questions: "Who were the other Negro boys from the corner?" "Where did all the white hoods come from?" It was obvious. Something was going to break loose, and I wanted to stop it. First, I

asked all the girls to leave, then the hoods. But before I could finish, trouble started. A white boy shoved a Negro boy. The manager then grabbed the white boy to push him out and was shoved by the white boy. The crowd followed. Outside the boy stood in the middle of the street daring any Negro to cross a certain line. He then pulled a car chain and claw hammer from his pocket and started swinging the chain in the air.

He stepped up his taunting with the encouragement of others. When we did not respond, he became so infuriated that he struck a Negro boy in the face with the chain. The boy kept walking. Then, in utter frustration, the white boy picked up a street sign and threw it at a Negro girl. It hit her and the fight began. The white boys, armed with chains, pipes and hammers, cut off an escape through the street. Negro boys grabbed the chains and beat the white boys. The hammers they threw away. The white boys went running back to their hot rods. I tried to order a retreat.

During the fight I had been talking to the store manager and to some newspaper men. I did not apologize for our sit-in -only for unwanted fighters of both races and for their conduct. Going

home, I was very dejected. I felt that this outbreak had killed our movement. I was not surprised the following day when a mob of 3,000 people formed. The fire department, all of the police force and police dogs were mobilized. The police turned the dogs loose on the Negroes -but not on the whites. Peaceful victory for us seemed distant.

Next day was rainy and I was thankful that at least no mob would form. At 10:00 a.m. I received a telephone call that was to change our whole course. Mr.Hamilton, director of the YMCA, urged me to bring a few students from the original sit-in group to a meeting that afternoon. I did. That meeting was with Gorgon Carey, a field secretary of CORE. We had seen his picture in the paper in connection with our recent campaign for integrated library facilities and we knew he was on our side. He had just left North Carolina where he had helped the student sit-ins. He told us about CORE and what CORE had done in similar situations elsewhere. I decided along with others, that Carey should help us organize a nonviolent, direct action group to continue our peaceful protests in Portsmouth. He

suggested that an all-day workshop on nonviolence be held February 20.

Rev. Chambers organized an adult committee to support our efforts. At the workshop we first oriented ourselves to CORE and its nonviolent methods. I spoke on "Why Nonviolent Action?" exploring Gandhi's principles of passive resistance and Martin Luther King's methods in Alabama. We then staged a socio-drama acting out the right and wrong ways to handle various demonstration situations. During the lunch recess, we had a real-life demonstration downtown -the first since the fighting. With our new methods and disciplined organization, we were successful in deterring violence. The store manager closed the counter early. We returned to the workshop, evaluated the day's sit-in and decided to continue in this manner. We established ourselves officially as the Student Movement for Racial Equality.

Since then, we have had no real trouble. Our struggle is not an easy one, but we know we are not alone and we plan to continue in accordance with our common ideal: equality for all through nonviolent action.

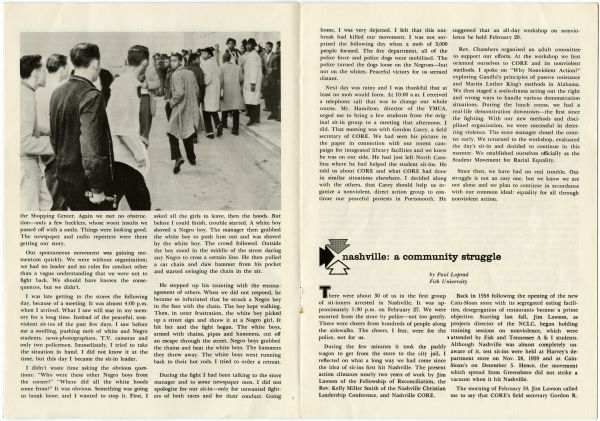

nashville: a community struggle

by Paul Laprad

Fisk University

There were about 30 of us in the first group of sit-inners arrest in Nashville. It was approximately 1:30 p.m. on February 27. We were escorted from the store by police -not too gently. There were cheers from hundreds of people along the sidewalks. The cheers, I fear, were for the police, not us.

During the few minutes it took the paddy wagon to get from the store to the city jail, I reflected on what a long way we had come since the idea of sit-ins first hit Nashville. The present action climaxes nearly two years of work by Jim Lawson of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the Rev. Kelly Miller Smith of the Nashville Christian Leadership Conference, and Nashville CORE.

Back in 1958 following the opening of the new Cain-Sloan store with its segregated eating facilities, desegregation of restaurants became a prime objective. Starting last fall, Jim Lawson, as projects director of the NCLC, began holding training sessions on nonviolence, which were attended by Fisk and Tennessee A & I students. Although Nashville was almost completely unaware of it, test sit-ins were held at Harvey's department store on Nov. 28, 1959 and at Cain-Sloan's on December 5. Hence, the movement which spread from Greensboro did not strike a vacuum when it hit Nashville.

The morning of February 10, Jim Lawson called me to say that CORE's field secretary Gordon R.

Carey and the Rev. Douglas Moore had called him from Durham asking Nashville to help the North Carolina sit-ins. I told him I would talk with some of the students on campus. They were quite excited over the North Carolina developments.

The next evening we were able to get together about 50 students from Fisk, A & I and American Baptist Theological Seminary. We decided to go into action and the first sit-in took place February 13. About 100 students participated -at three stores: Woolworth's McLellan's and Kress's. We were refused service and remained seated until the stores closed. There was no hostility. Five days later, we tried again. This time 200 students took part and we were able to cover a fourth store, Grant's.

First sign of possible violence came on February 20, a Saturday, with school out and the white teenagers downtown. Some of them jeered at the demonstrators. At Walgreens, the fifth store to be covered, a boy got into a violent argument with the white co-ed from Fisk.

Police were present during all of these sit-ins, but did not make arrests or attempt to interfere with the demonstrators. Between February 20 and 27, however, a merchants committee called upon Mayor Ben West to halt the sit-ins. He said city attorneys had advised him that anyone has the right to sit at a lunch counter and request service. However, he expressed the viewpoint that it is a violation of law to remain at a lunch counter after it has been closed to the public.

This set the stage for February 27, again a Saturday. Every available man on the police force had been ordered into the downtown area at the time of our demonstration. I was with the student group which went to Woolworth's. Curiously, no police were inside the stores when white teenagers and others stood in the aisles insulting us, blowing smoke in our faces, grinding out cigarette butts on our backs and finally, pulling us off our stools and beating us. Those of us pulled off our seats tried to regain them as soon as possible. But none of us attempted to fight back in any way.

Failing to disrupt the sit-ins, the white teenagers filed out. Two or three minutes later, the police entered and told us we were under arrest. To date, none of the whites who attacked us have been arrested, although Police Chief D.E. Hosse has ordered an investigation to find out why.

As might be expected, even the jail cells in Nashville are segregated. Two other white students and I were isolated from the others in a fairly large room, but we managed to join in the singing which came from the horribly crowded cells where the Negro students were confined.

There were 81 of us, in all, arrested that day. We hadn't been in jail more than a half hour before food was sent into us by the Negro merchants. A call for bail was issued to the Negro community and within a couple of hours there was twice the amount needed.

Our trials were February 29. The regular city judge refused on a technicality to handle the cases and appointed a special judge whose bias was so flagrant that Negro lawyers defending us were shocked. At one point, Z. Alexander Looby, a well-known NAACP attorney and City Council member, threw up his hands and commented: "What's the use!" During the two days I sat in court, every policeman who testified under oath, stated that we had been sitting quietly at the lunch counters and doing nothing else.

The judge's verdict on disorderly conduct charges was "guilty." Most of us were fined $50 and costs. A few of the cases are being appealed as test cases. Next, we were all re-arrested on state charges of conspiracy to obstruct trade and commerce, but the district attorney general has expressed doubts as to the validity of this charge and to date no indictments have been returned by the grand jury.

On March 2 another 63 students were arrested at Nashville's two bus stations -Greyhound and Trailways. They too were charged with disorderly conduct and then conspiracy. It began to look as though we might fill the jails. The next day, however, a new development occurred. At the urging of the Friends Meeting, the Community Relations Conference, the Ministerial Association and other groups, Mayor West appointed a 7-man bi-racial committee to try to work out a solution.

Although some Negroes expressed doubts about whether the committee was truly representative, we decided to discontinue the sit-ins temporarily to give it a chance to deliberate. However a boycott of the stores by the Negro community started at this time. By March 25 we felt the committee had had sufficient time to answer what is essentially a moral problem and we took action again. This time we covered an additional drugstore, Harvey's and Cain & Sloan's. Only four students

were arrested -all at the drugstore. Police appeared to have received orders not to molest us.

This sit-in provoked a violent reaction from Governor Buford Ellington, who charged that it was "instigated and planned by and staged for convenience of Columbia Broadcasting System." The charge stemmed from the fact that two CBS documentary teams had been with us for a week, filming our meetings and getting material for "Anatomy of a Demonstration." Of course, the idea that we would stage a sit-in purely for convenience or cameramen is too ridiculous.

Meanwhile, the first breaks in the pattern had occurred. On March 16, four Negro students were served at the Greyhound bus station (see photo).

The Mayor's committee announced it had been ready to report but, because of the March 25 sit-in, was unable to do so. On April 5 the committee recommended that for a 90-day trial period the stores "make available to all customers a portion of restaurant facilities now operated exclusively for white customers" and that pending cases against the sit-in participants be dropped.

The plan of the Mayor's committee was rejected by the store management and by the student leaders. The students said "The suggestion of a restricted area involves the same stigma of which we are earnestly trying to rid the community. The

plan presented by the Mayor's Committee ignores the moral issues involved in the struggle for human rights." We were not prepared to accept "integrated facilities" while "whites only" counters were maintained.

Demonstrations were resumed April 11.

One final note should be added about the effects of the sit-ins here. They have unified the Negro community in an unprecedented manner. The boycott proved effective in sharply curtailing season Easter business in the variety stores. On April 19, within only a few hours after the bombing of Looby's home, over 2500 demonstrators marched on City Hall. Adult leaders have assured us that, even if the students suddenly vanished from the scene, the action campaign would continue unabated. In Nashville, this is not a student-only struggle.

I could not close without reference to the academic freedom fight involving Jim Lawson, one of three Negro students at Vanderbilt's divinity school. He was expelled March 3 because of his "strong commitment to a planned campaign of civil disobedience." He did not actually participate in the sit-ins, but he has been our advisor and counselor throughout. His expulsion has touched off a storm of protest not only in Nashville but in academic and ministerial circles from coast to coast.

orangeburg: behind the carolina stockade

by Thomas Gaither

Claflin College

On March 16 many newspapers throughout the world carried a photo showing 350 arrested students herded into an open-air stockade in Orangeburg, South Carolina.

I was arrested later in the day while marching in protest in front of the courthouse. i didn't realize until scrutinizing the stockade photo much later, that the scene shown was unusual -to say the least -and would later provoke questions from newspaper readers unfamiliar with the local scene.

What were all these well-dressed, peaceable-looking students doing in a stockade? Why weren't they inside the jail if they were under arrest? How come that such un-criminal-appearing youths were arrested in the first place?

The story begins about a month before when we students in the Orangeburg area became inspired by the example of the students in Rock Hill, South Carolina city where lunch counter sit-ins occurred. We, too, feel that stores which graciously accept our money at one counter, should not rudely refuse it at another. We decided to request service at Kress's lunch counter.

But first, we felt that training in the principles and practice of nonviolence was needed. We formed classes of about 40 students each over a period of three to four days. Our chief texts were the pamphlet "CORE Rules for Action" and Martin Luther King's inspirational book, "Stride Toward Freedom." In these sessions we emphasized adherence to nonviolence and discussed various situations which might provoke violence. Could each one of us trust our God and our temper enough to not strike back even if kicked, slapped or spit upon? Many felt they could

discipline themselves in violent situations. Others were honest enough to admit they could not and decided not to participate until they felt surer of themselves on this issue.

After the initial briefing session, two group spokesmen were chosen: one from Claflin College and one from South Carolina State College. Their duty was to chart action plans for February 25. They checked the entrances of the Kress store and counted the number of stools at the lunch counter. The number of minutes it takes to walk from a central point of campus to Kress's was timed exactly. From our training groups, we picked 40 students who felt confident in the techniques of nonviolence. After further training and some prayer we felt prepared for action.

At 10:45 a.m. on February 25, students from Claflin and South Carolina State left their respective campuses in groups of three or four, with one person designated as group leader. The groups followed three routes, walking at a moderate pace, which would ensure their arriving at the store simultaneously.

The fifteen students went in and sat down at the lunch counter. After they had been there about a quarter of an hour, signs were posted saying that the counters were closed in the interest of public safety.

The first group then left and another group of about 20 students took their seats. The manager then started removing the seats from the stands. Each student remained seated until his seat was removed. A few students were jostled by police. A number of hoodlums were in the store, some of whom carried large knives and other weapons, unconcealed. However, no violence occurred. By closing time the seats were still off their stands and nobody was being served.

We returned to the store the next day, following the same plan of action. At first the seats were still down but by 11:30 those at one end of the counter were screwed on and some white people were served. We students stood along the rest of the counter until 3:30. By this time, additional students had joined us and we were several rows deep. At 4, the store closed.

The next day, Saturday, we decided against sitting-in. We had sought and obtained clearance from the chief of police to picket and we were prepared to start Monday. However, no sooner had some 25 students started picketing than they were ordered to remove their signs or face arrest. They were informed that an anti-picketing ordinance had been enacted that same day.

Inside the store, the counters were stacked with trash cans. Not more than two Negroes at a time were permitted to enter. Each day our spokesmen checked the counter. Meanwhile some 1,000 Claflin and South Carolina State students were receiving training for the mass demonstrations which were to follow.

The first such demonstration started at 12:30 on March 1. over 1,000 students marched through the streets of Orangeburg with signs saying: "All Sit or All Stand," "Segregation is Obsolete," "No Color Line in Heaven and Down With Jim-crow."

Not long after reaching the main street, the marchers were met by a contingent of state police who requested identification of leaders and asked that the signs be taken down. The group leaders were informed that they would be held responsible for any outbreak of violence and that if this occurred, they would be charged with inciting to riot. There was no violence. Only two persons were arrested, and these were not participants.

After the March 1 demonstration, the lunch counters were closed for two weeks. With a view to strengthening our local movement and broadening it on a statewide basis, the South Carolina Student Movement Association was established. I was named chairman of the Orangeburg branch. We initiated a boycott of stores whose lunch counters discriminate.

March 15 was the day of the big march -the one in which 350 students landed in the stockade. The lunch counters had reopened the previous day and a sit-in was planned in addition to the march. Governor Hollings had asserted that no such demonstration would be tolerated. Regarding us, he said: "They think they can violate any law, especially if they have a Bible in their hands: our law enforcement officers have their Bibles too."

Of course, we were violating no law with our peaceful demonstration. As for the law enforcement officers having their Bibles, they may have them at home, but what they had in their hands the day of our demonstration were tear gas bombs and firehoses, which they used indiscriminately. The weather was sub-freezing and we were completely drenched with water from the hoses. Many

of the girls were knocked off their feet by the pressure and floundered around in the water. Among the students thrown by the water were several physically handicapped students -one of them a blind girl.

Over 500 students were arrested. 150 filled the city and county jails. That's why some 350 were jammed into the stockade, surrounded by a heavy wire fence about seven feet high. The enclosure ordinarily serves as a chicken coop and storage space for chicken feed and lumber. There are two tall iron gates. It afforded no shelter whatsoever in the sub-freezing weather.

In contrast to the cold outside, students in the jail's basement were sweating in 90-degree temperatures emanating from the boiler room. One student drenched from head to toe was locked in solitary in a cell with water three inches deep. Requests for dry clothing were denied. The Claflin College nurse who came to give first aid was halted at the court house entrance and literally had to force her way inside.

I was arrested with a group of some 200 students marching around the court house in protest over the earlier mass arrests. At first police told us we would be permitted to march if we kept moving in a orderly manner but then they announced that unless we returned to the campus at once we would be arrested. I was seized as one of the leaders and was held in jail for four hours.

The trials of the arrested students started next day, a few students at a time. All were eventually convicted of "breach of the peace" and sentenced to 30 days in jail or $100 fine. The cases are being appealed to the higher courts.

Meanwhile, our action program proceeds. We are set in our goal and, with the help of God, nothing will stop us short of that goal.

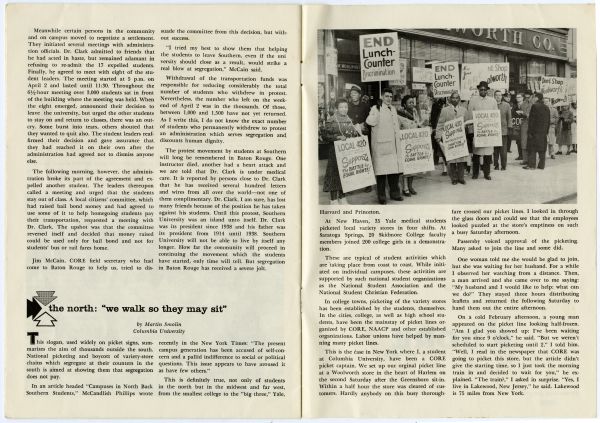

baton rouge: higher education - southern style

by Major Johns

Southern University

(till March 30 when he was expelled for his role in the student protest)

Some Negro University and College administrations have supported their students' lunch counter sit-ins or, at least, have remained neutral. Others have taken a stand in opposition to the students. Southern University in Baton Rouge and its president, Dr. Felton G. Clark fall in this latter category.

Dr. Clark had the opportunity of taking a courageous position and becoming one of the world's most respected educational leaders. Instead, he chose to buckle-under to the all-white State Board of Education, which administers the university.

Early in march the Board issued a warning that any student participating in a sit-in would be subject to "stern disciplinary action." The sit-in movement had not yet spread to Baton Rouge but, as one law student expressed it: "When the Board spoke, it became a challenge to us and we could not ignore it." A representative student committee then met with Dr. Clark and asked, specifically, what would happen to students who sat-in. He replied that the Board had left him no alternative but to expel them.

On March 28 seven students sat-in at the Kress lunch counter. In less than 20 minutes they were arrested. Bond was set at the astronomical figure of $1,500 each. However, the money was promptly raised by the Negro community and the students were released. A mass meeting was held on campus at which students engaged in sit-ins at Sitman's drugstore and at the Greyhound bus station. They remained in jail six days pending a court hearing and were released on bond April 4.

The day after the second arrests, 3,500 students marched through the center of town to the State Capitol, where we held an hour-long prayer meeting. As chief speaker, I attacked segregation and discrimination not only here in Baton Rouge but in other parts of the country.

I was unaware that this speech would sever my connections with the university before the day was over. That afternoon Dr. Clark returned from a conference in Washington and immediately cast his lot against the students. He summoned faculty members who were known to oppose the sit-ins and were furthest removed from really knowing the students. Immediately following this meeting, he announced the expulsion of 17 students, the 16 who had participated in the two sit-ins and myself.

This suddenly shifted the focus of the Baton Rouge student protest from lunch counters to the university administration. As Marvin Robinson, participant in the first sit-in and president of the senior class expressed it, we had a choice: "Which is the more important, human dignity or the university? We felt it was human dignity."

The students voted to boycott all classes until the 17 of us were reinstated. Lines were tightly drawn: the students on one side, the administration, faculty, State Board of Education, and a group of hand-picked alumni on the other. We 17 were no longer permitted on campus. But twice daily, in the morning and afternoon, we would address the students from the balcony of a 2-story house across a railroad track from the campus. By using a loudspeaker we were able to make ourselves heard by the large groups of students assembled on the campus-side of the track. This went on for two days.

Unable to get the students back to class, administration officials started calling their parents and telling them that the student leaders were inciting to riot. This move boomeranged: it caused many parents to fear for their sons' and daughters' safety to the extent of summoning them home. The administration countered by announcing that any student who wanted to withdraw from the university and go home could do so. Such a sizable number of students applied at the registrar's office for withdrawal slips (see photo) that the administration amended its ruling to the effect that these slips would have to be co-signed by parents.

Meanwhile certain persons in the community and on campus moved to negotiate a settlement. They initiated several meetings with administration officials. Dr. Clark admitted to friends that he had acted in haste, but remained adamant in refusing to re-admit the 17 expelled students. Finally, he agreed to meet with eight of the student leaders. The meeting started at 5 p.m. on April 2 and lasted until 11:30. Throughout the 6 1/2-hour meeting over 3,000 students sat in front of the building where the meeting was held. When the eight emerged, announced their decision to leave the university, but urged the other students to stay on and return to classes, there was an outcry. Some burst into tears, others shouted that they wanted to quit also. The student leaders reaffirmed their decision and gave assurance that they had reached it on their own after the administration had agreed not to dismiss anyone else.

The following morning, however, the administration broke its part of the agreement and expelled another student. The leaders thereupon called a meeting and urged that the students stay out of class. A local citizens' committee, which had raised bail bond money and had agreed to use some of it to help homegoing students pay their transportation, requested a meeting with Dr. Clark. The upshot was that the committee reversed itself and decided that money raised could be used only for bail bond and not for students' bus or rail fares home.

Jim McCain, CORE field secretary who had come to Baton Rouge to help us, tried to dissuade the committee from this decision, but without success.

"I tried my best to show them that helping the students to leave Southern, even if the university should close as a result, would strike a real blow at segregation," McCain said.

Withdrawal of the transportation funds was responsible for reducing considerably the total number of students who withdrew in protest. Nevertheless, the number who left on the weekend of April 2 was in the thousands. Of those, between 1,000 and 1,500 have not yet returned. As I write this, I do not know the exact number of students who permanently withdrew to protest an administration which serves segregation and discounts human dignity.

The protest movement by students at Southern will long be remembered in Baton Rouge. One instructor died, another had a heart attack and we are told that Dr. Clark is under medical care. It is reported by persons close to Dr. Clark that he has received several hundred letters and wires from all over the world -not one of them complimentary. Dr. Clark, I am sure, has lost many friends because of the position he has taken against his students. Until this protest, Southern University was an island unto itself. Dr. Clark was its president since 1938 and his father was its president from 1914 until 1938. Southern University will not be able to live by itself any longer. How far the community will proceed in continuing the movement which the students have started, only time will tell. But segregation in Baton Rouge has received a severe jolt.

the north: "we walk so they may sit"

by Martin Smolin

Columbia University

This slogan, used widely on picket signs, summarizes the aim of thousands outside the south. National picketing and boycott of variety-store chains which segregate at their counters in the south is aimed at showing them that segregation does not pay.

In an article headed "Campuses in North Back Southern Students," McCandlish Phillips wrote recently in the New York Times: "The present campus generation has been accused of self-concern and a pallid indifference to social or political questions. This issue appears to have aroused it as have few others."

This is definitely true, not only of students in the north but in the midwest and far west, from the smallest college to the "big three," Yale, Harvard and Princeton.

At New Haven, 35 Yale medical students picketed local variety stores in four shifts. At Saratoga Springs, 20 Skidmore College faculty members joined 200 college girls in a demonstration.

These are typical of student activities which are taking place from coast to coast. While initiated on individual campuses, these activities are supported by such national student organizations as the National Student Association and the National Student Christian Federation.

In college towns, picketing of the variety stores has been established by the students, themselves. In cities, college, as well as high school students, have been the mainstay of picket lines organized by CORE, NAACP and other established organizations. Labor unions have helped by manning many picket lines.

This is the case in New York where I, a student at Columbia University, have been a CORE picket captain. We set up our original picket line at a Woolworth store in the heart of Harlem on the second Saturday after the Greensboro sit-in. Within a half hour the store was cleared of customers. Hardly anybody on this busy thoroughfare crossed our picket lines. I looked in through the glass doors and could see that the employees looked puzzled at the store's emptiness on such a busy afternoon.

Passerby voiced approval of the picketing. Many asked to join the line and some did.

One woman told me she would be glad to join but she was waiting for her husband. For a while I observed her watching from a distance. Then a man arrived and she came over to me saying: "My husband and I would like to help: what can we do?" They stayed three hours distributing leaflets and returned the following Saturday to hand them out the entire afternoon.

On a cold February afternoon, a young man appeared on the picket line looking half-frozen. "Am I glad you showed up: I've been waiting for you since 9 o'clock," he said. "But we weren't scheduled to start picketing until 2," I told him. "Well, I read in the newspaper that CORE was going to picket this store, but the article didn't give the starting time, so I just took the morning train in and decided to wait for you," he explained. "The train?" I asked in surprise. "Yes, I live in Lakewood, New Jersey," he said. Lakewood is 75 miles from New York.

Not everyone is this devoted, yet this is not an untypical example of the support our picket lines have received. At one Woolworth store the manager himself, expressed support. As we were about to end our picketing for the day, he signaled to me and said: "I've heard about the work you people are doing and agree with you 100%. I think we must integrate our stores in the South."

At another Woolworth store, a Bible concessionaire came out and told me: "You're losing me business like crazy -but don't stop. I'd even join you if I didn't have my concession here." As he went back into the store, he added: I guess people have been reading my product lately."

When nine southern students whom CORE brought north to tell their story, joined our picket on 125th Street, I asked how it made them feel to observe our activities in this part of the country. "It makes us feel that we are not alone in our struggle," is the way Merritt Spaulding, a student who had been arrested in Tallahassee, expressed it. This, together with the sympathy demonstrated each week on the picket line, has given me great encouragement.

People have asked me why northerners-especially white people who have been in the majority in our picket demonstrations in New York-take an active part in an issue which doesn't concern them. My answer is that injustice anywhere is everybody's concern.

Sitting at a lunch counter may seem like a small thing to some, but the right to do so is inextricably bound up with the American idea of equality for all. The world's eyes are upon us. We and our democracy are on trial. All of us are being judged by what occurred in Little Rock in recent years and by what is happening in the south today.

That is why students in the north have identified themselves with the movement in the south. U.S. students have been challenged to shake off their traditional political apathy and take a stand.

As a student at Columbia University and as a member of New York CORE, I am aware that northern students have wanted to speak out for integration for some time. But aside from listening to speeches with which we agreed -there was little to do.

We were waiting for the leadership to come from the south. Now, the lunch counter sit-ins have given us the awaited opportunity to act. We intend to keep up the picketing and the boycott of variety stores until lunch counters discrimination is eliminated in the south -as it has been in other parts of the country.

Compiled and edited by Jim Peck

Designed by Jerry Goldman

Published May 1960 by

CONGRESS OF RACIAL Equality

CORE

38 PARK ROW, NEW YORK 38, N.Y.

Price -25¢ per copy.

Reductions on Quantity Orders.

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program