Description of previous item

Description of next item

Dispatches from the Florida Capital

Published June 6, 2017 by Florida Memory

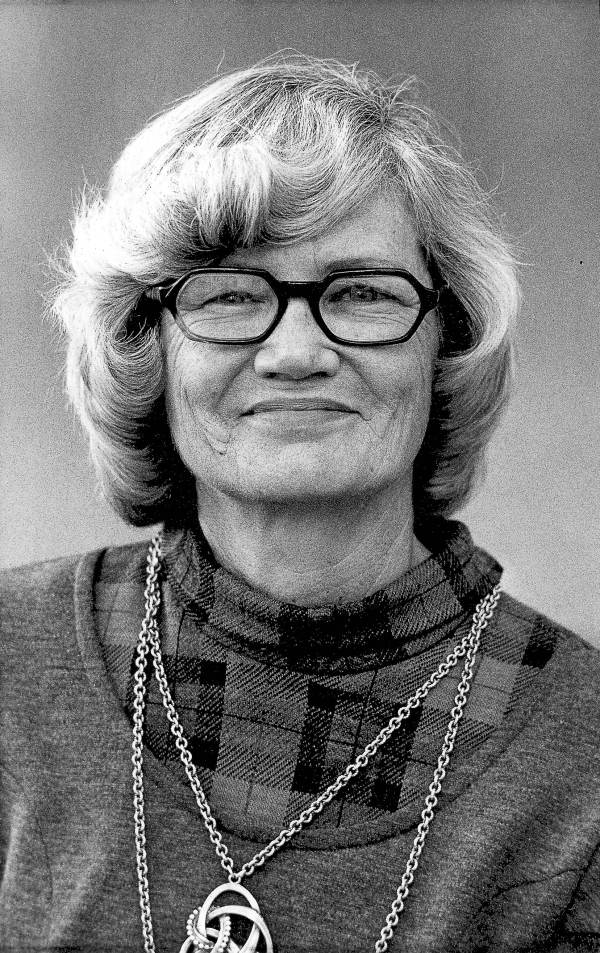

Spot a politician in the Florida state Capitol building and expect to find a gaggle of reporters nearby, vying to scoop the latest story. While some of today’s bylines carry more weight than others, from 1944 to 1982 United Press International (UPI) reporter Barbara Landstreet Frye dominated Florida’s state politics beat. Dubbed the dean of Tallahassee’s correspondents, Frye’s no-frills, objective style journalism is credited with changing the direction of Florida government. The veteran reporter covered the administrations of 11 Florida governors, dozens of legislative sessions, state courts and a stream of other political events that have since made Florida history.

But Frye broke more than news during her 38-year tenure. As the first female reporter to cover Florida’s capital politics, she broke barriers for future generations of women journalists. “She was a liberated woman long before anyone used that term… She competed against all-male competition in the early days, and she beat them,” remembered former Tallahassee Democrat editor Bill Mansfield. Once declared “an institution” by clerk of the Florida House and founder of the Florida Photographic Collection Allen Morris, Frye’s unmatched work ethic and passion for Florida politics cemented her legacy as a pioneering woman in journalism.

When Barbara Frye was born Barbara Landstreet in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1922, only a handful of women worked in the male-dominated news business. But this prevailing reality did not stop Landstreet from pursuing a journalism degree at the University of Georgia. Upon graduating in 1943, the United Press Association (UPI’s predecessor) offered Landstreet a reporting position in Atlanta.

But there was just one minor problem: she was already engaged to marry her college boyfriend. In those days, married middle-class women didn’t work if they could help it. Moreover, Landstreet recognized the fleeting pretext of the job offer–with so many American men fighting in WWII, employers sought female talent to fill in the temporary wartime gaps. In a career-defining moment, the aspiring reporter bucked societal expectations, broke off the engagement and boarded a train for the Georgia capital. “I just couldn’t resist an offer from a big wire service.”

After a nine month stint in Atlanta, UPI promoted the fresh-faced 22-year-old co-ed to head up the new Tallahassee Bureau–a job she hesitated to accept at first: “My family was in Atlanta and I had never been out on my own before. I was nearly in tears, I had never even heard of Tallahassee.” Despite these initial reservations, Landstreet made the move.

On the train ride down to Florida’s capital city, she happened to sit next to a hospitable woman focused on easing the young reporter’s fears. The woman turned out to be Florida’s First Lady Mary Groover Holland and she extended a dinner invitation to the newcomer. The UPI bureau chief ate her inaugural Tallahassee meal at the Florida Governor’s Mansion in the company of Governor Spessard Holland and family. On her first night in town, Landstreet was already gathering political sources, a skill that would help earn her an impeccable reputation as one of Florida’s top political reporters.

Soon after arriving in Tallahassee, Landstreet met and married former director of the state Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission Dr. Earl O. Frye. From then on, her byline read simply Barbara Frye (UPI). “I never planned a career when I started work. I always envisioned myself as working a few years, getting married and becoming a housewife.”

But the grip of Florida’s evolving twentieth century political landscape held Frye in the press gallery at the Capitol for almost four decades. In that time, she sat through countless dull government meetings and traveled all over the state to interview sources, all the while remaining dedicated to informing the public on the latest developments in Florida politics.

Capitol Press Corps interviewing Governor Fuller Warren at the Silver Slipper restaurant in Tallahassee, 1949. Frye is pictured second from left.

“She came here almost as a bobby-soxer. I can remember when she first came she was such a spry, attractive person,” remembered Governor LeRoy Collins. When she first started writing about Florida politics, only a handful of reporters covered the state Capitol and Frye was the only woman in the group. “At first no one took me very seriously because they simply were not used to women covering the news here.” In an era when editors often assigned “fluff” pieces to female reporters, Frye fought hard to cover meatier topics. Described by a friend as a “mix of old south and modern feminist,” her disarming southern lilt fit right in with Florida’s “good old boy” political climate of the 1940s and 50s–and helped bridge some initial gender barriers.

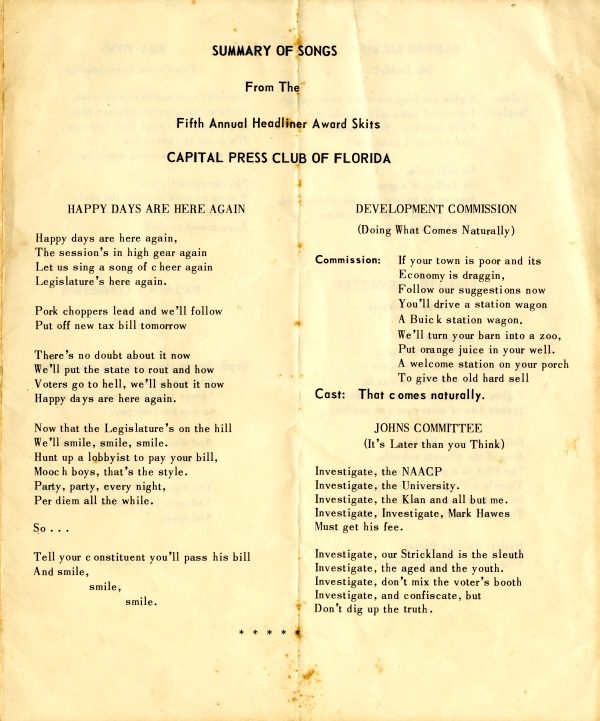

Program from the fifth annual Capital [sic.] Press Club Skits, ca. 1955. William T. Cash Collection (N2004-5, Box 04, Folder 13), State Archives of Florida. Since the 1940s, Tallahassee’s legislative correspondents have put on the press skits at the start of each legislative session, satirizing lawmakers. As a member of the press club, Barbara Frye participated in a number of skits over the years.

By the 1950s, every reporter, politico and pundit in the state not only knew Barbara Frye’s byline but implicitly trusted the accuracy of her reporting. Veteran Florida political writer Martin Dyckman remembered one telling anecdote from the Governor Reubin Askew era: Frye had mistakenly filed a story with the lede “Gov. LeRoy Collins today…” and it almost went unnoticed.

Barbara Frye sits with other members of the Capitol Press Corps covering the Bay County High School awards ceremonies for March of Dimes, 1962. Photo by Jim Stokes.

Barbara Frye with Governor Reubin Askew, Congressman Bill Young and Florida Secretary of State Richard Stone, 1976. Photo by Don Dughi.

Frye cultivated close relationships with her political subjects, winning high praise from several of Florida’s governors. “I think the way she helped me more than any other way was in her expectation that my conduct would measure up,” said Governor Collins. “She expected the most of me and I felt if I didn’t measure up, she would be disappointed,” he continued. Echoing Collins, Governor Askew characterized Frye as “a woman who, in her own way, constantly challenged those who held positions of public trust to realize their potential as public servant.” Her own public service work extended beyond the press corps, as she was also an active member of the Tiger Bay Club, Junior League and the Statewide Citizens Council on Drug Abuse.

At the height of her dynamic journalism career, while other reporters scrambled to track down sources, tipsters frequently sought the ear of the UPI bureau chief. Sources offered Frye exclusive information because they trusted her news judgement.

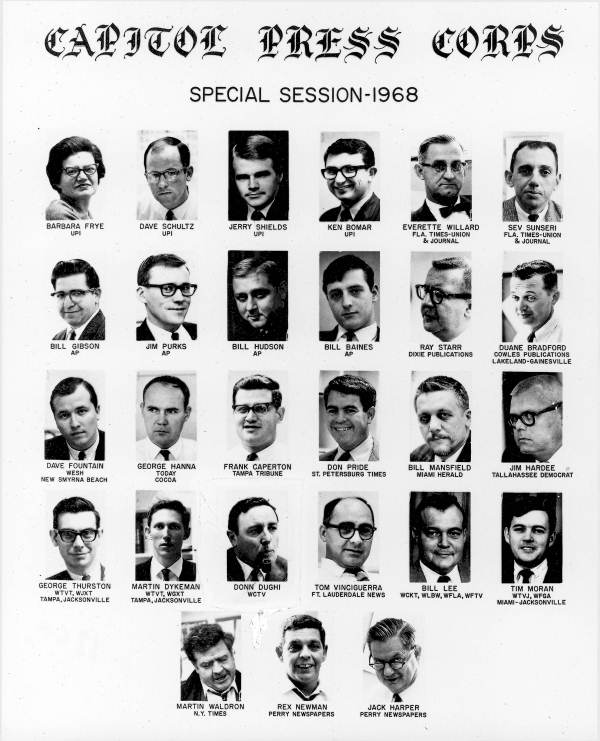

Members of the Capitol Press Corps covering the 1968 special legislative session. Note that Barbara Frye, pictured top left, is the only woman in the corps.

From special elections to legislative reapportionment, Frye meticulously drafted an almost half-century’s worth of Florida history with speed, precision and her own personal flair.

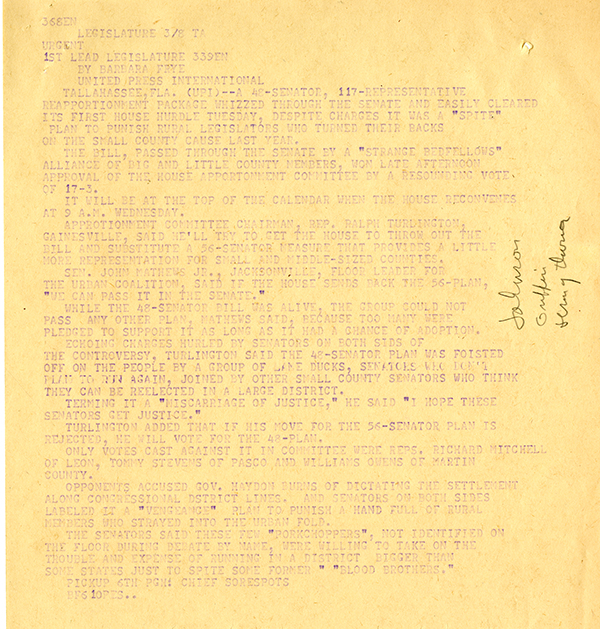

UPI article by Barbara Frye regarding the 1967 Special Legislative Session on reapportionment. Barbara Frye Press Files Collection (M90-18), Box 5, Folder 17, State Archives of Florida. Frye wrote most of her articles on a teletype machine, unable to see the words she was typing. Her work was then transmitted over the UPI wire service and printed.

Before reaching middle age, Frye had become a living legend at the Florida Capitol. Frye set the standard for good journalism in Tallahassee and mentored many up-and-coming Tallahassee reporters over the years, especially young women.

Former statehouse reporter turned Leon County Commissioner Mary Ann Lindley, longtime Tallahassee Democrat journalist Bill Cotterell and retired editor of the St.Petersburg Times Martin Dyckman all learned the ropes from Frye. “Barbara could, and would, teach anybody – including competitors – about state government,” remembered Cotterell. “She was never too big to lend a hand to green frightened reporters covering the big beat for the first time. She never forgot the tears and apprehension she had on the night train from Atlanta so long ago,” reminisced Dyckman.

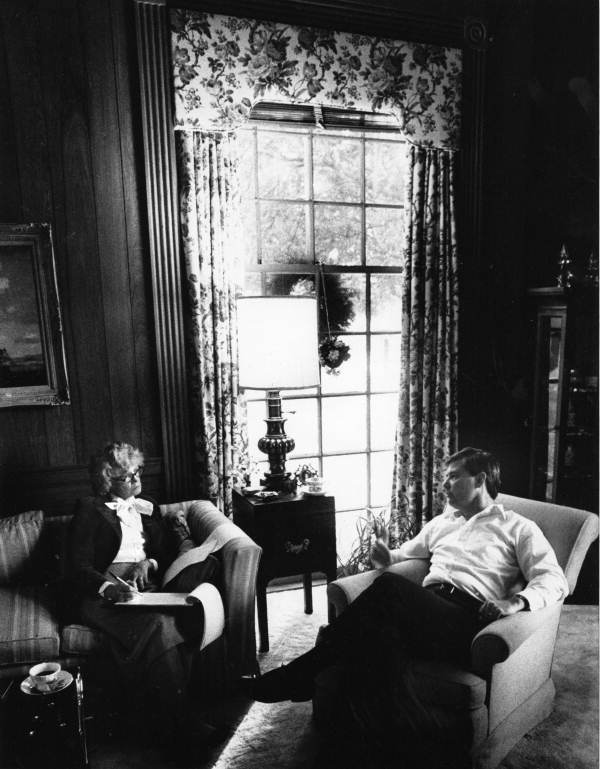

Barbara Frye interviewing Governor Bob Graham at the Governor’s Mansion in Tallahassee, ca. 1979. Graham’s was the last administration Frye reported on before her death in 1982.

Though her editor at UPI offered Frye a string of different jobs in Washington, she turned them all down, citing her unbridled enthusiasm for writing about Florida’s steamy politics.

Frye never missed a day of work, until she was diagnosed with cancer in 1981. Even still, she continued reporting on select happenings downtown throughout most of her illness. “I thought I was immortal…. I thought I’d be the last person left. I never thought cancer,” Frye reconciled in an interview during the last year of her life. The Florida Capitol mourned when 60-year-old Barbara Landstreet Frye died at Tallahassee Memorial Hospital on May 22, 1982.

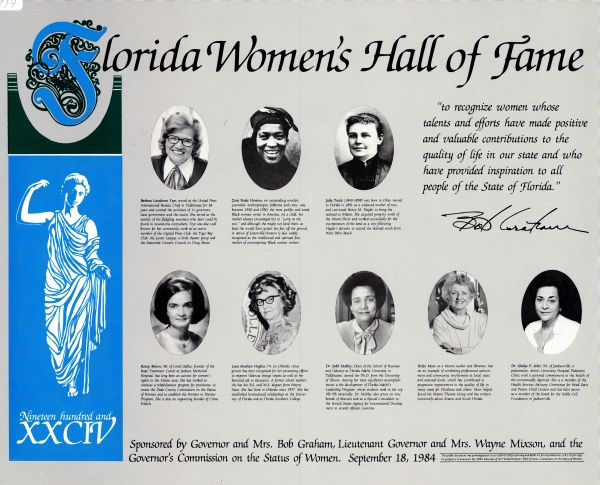

Poster of 1984 Florida Women’s Hall of Fame inductees, State Library of Florida. Barbara Frye is pictured on the top left.

Once known as a living legend, Frye has continued to maintain a legendary status some 35 years after her death. Immediately following her passing, the Capitol Press Club of Florida created the Barbara L. Frye Scholarship which awards annual prizes to aspiring young journalists. Additionally, in 1984, the Governor’s Commission on the Status of Women posthumously elected Frye to the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame; the Florida Press Association Hall of Fame also honored her in 1990. That same year, the State Archives of Florida acquired the esteemed journalist’s press files, where the story of her legendary career as one of the nation’s trailblazing female political reporters lives on.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Dispatches from the Florida Capital." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332713.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Dispatches from the Florida Capital." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332713. Accessed March 10, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, June 6). Dispatches from the Florida Capital. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332713

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program