Description of previous item

Description of next item

The Taylor Family Papers: Using Plantation Records for Researching Enslaved People

Published August 8, 2017 by Florida Memory

Finding personal details of enslaved people prior to the end of the Civil War can be difficult. The basic tool that many use for researching American ancestors, the United States population census, did not name slaves. The census slave schedules, taken in 1850 and 1860, listed the slave owner’s name and slaves by sex and age only, with occasional exceptions to this rule. Sometimes, court documents, such as wills and probate proceedings, bills of sale and, rarely, plantation records, also include personal information about slaves.

Journals, ledgers and other personal records can likewise prove useful for researchers. Though records from Florida antebellum plantations tend to be scarce, when they have been preserved, they can often yield valuable information about slaves. Using records housed at the State Archives, we will demonstrate how genealogical researchers can use some of the resources listed above to find valuable information about enslaved ancestors.

In collection M83-27, Taylor Family Papers, among a number of letters detailing the genealogical history of a group of allied North Florida families is a remarkable journal kept by Elizabeth L. (Grice) Taylor (1830-1888). The journal records the movement of her family from North Carolina to Leon County, Florida, and then around North Florida to various plantations. In addition to listing births and other important events in her own extended family, she also documented the names, ages, births and deaths of some of their slaves.

On the first page of her journal, Elizabeth noted the names and birthdates of her own children, Sarah, Elizabeth Roberta, Charles, Catherine, William Jr. and Leslie. On the second page, titled “Black Creek, Jan. 4th, 1851” and subtitled “Negroe ages,” she listed the birth dates of children born to the enslaved women between 1850 and 1858. On subsequent pages are additional birth dates and death dates of slaves. She also made a timeline for the various places the family moved to in Leon, Wakulla and Madison counties.

The dates and locations of residence that Elizabeth noted in her timeline can be especially useful for structuring a search for other records; a researcher will have a better general idea of what kind of records and particular repositories to search for the Taylors and any documentation on the slaves. Knowing the dates allows researchers to conduct a more targeted search.

1850-1865

William N. Taylor (1825-1896) and Elizabeth L. Grice were married July 24, 1850, in North Carolina. They left North Carolina on the 30th of September for a honeymoon trip to New York and arrived in Florida on the 6th of October. They arrived after the census was taken that year, so they were not recorded in a Florida census until 1860.

From 1850-1855, the Taylor family and their slaves lived at Black Creek Plantation, Leon County, in the Miccosukee area. Elizabeth noted birth dates of the slaves at that time:

“Mary Brown was born about 1831

Mary’s child – George was born 20th of July 1850

Fanny was born 29 November 1852

Harriet was born 1839 – month not known

Mary Branson’s child – Charles was born 22 March 1853

Maria was born March 25th 1855

Lizzie was born August 1854

Bell’s boy Bull S. born April 1st, 1855

Pleasant, Till’s babe born January 1855″

Between 1855 and 1861, the Taylors lived at The Pinewoods in Wakulla County. During that time, Elizabeth noted the following slave births:

“Florence born April 1856

Lany’s boy born August 15, 1856

Emily born July 1857

Ellen born January 22, 1858

Allmand born November 16th, 1858

Dora Ansy, Till’s 3rd daughter was born July 1860

Capitola, Mary’s daughter, was born February 1860

Austin Till’s boy born August 11, 1863″

She recorded deaths on separate pages, one also labeled “Negroes”:

“Mary Branson died Jan 18th 1860

Mary Brown died August 2nd 1867

Maria died October 1859

Emanuel died Nov 1857

Emily died Sep 1859

Capitola, Feb 1860

Vina and Hepsy died August 1850

Old Dr Alick died January 22, 1863

Dora, Till’s daughter died June 8th 1863″

One of the letters in the Taylor Family Papers mentioned an 1858 bill of sale in the Wakulla County Courthouse between William N. Taylor and James M. Shine. This deed record confirms many of the names in the journal, adds several other individuals, and reveals mother-child relationships not noted by Elizabeth.

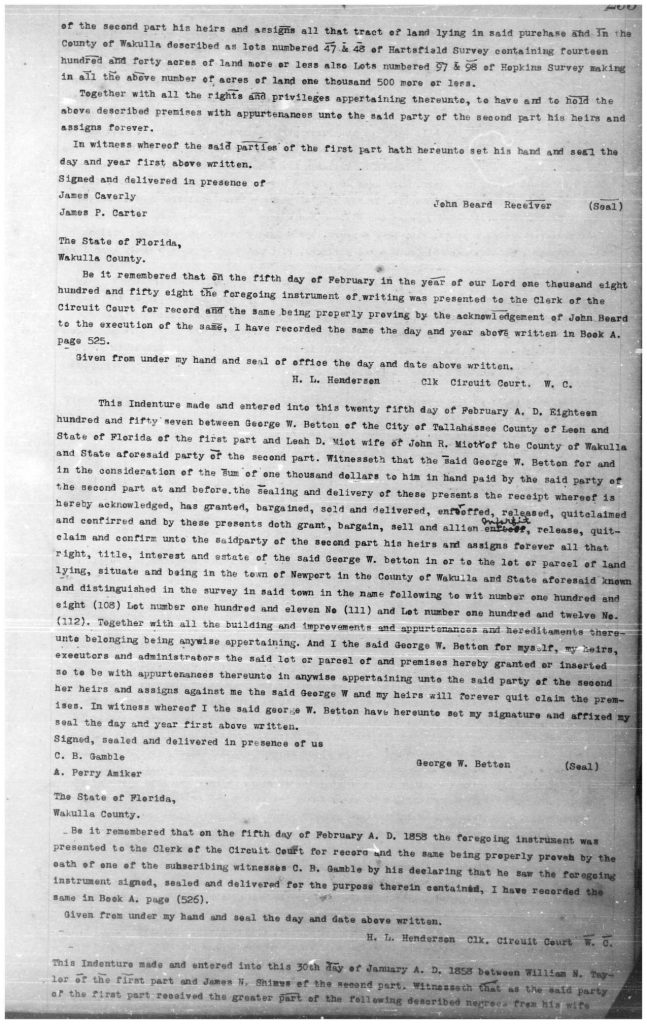

Deed between William N. Taylor and James M. Shine from Wakulla County Courthouse, Deed Records Book A-B, February 5, 1858, page 295.

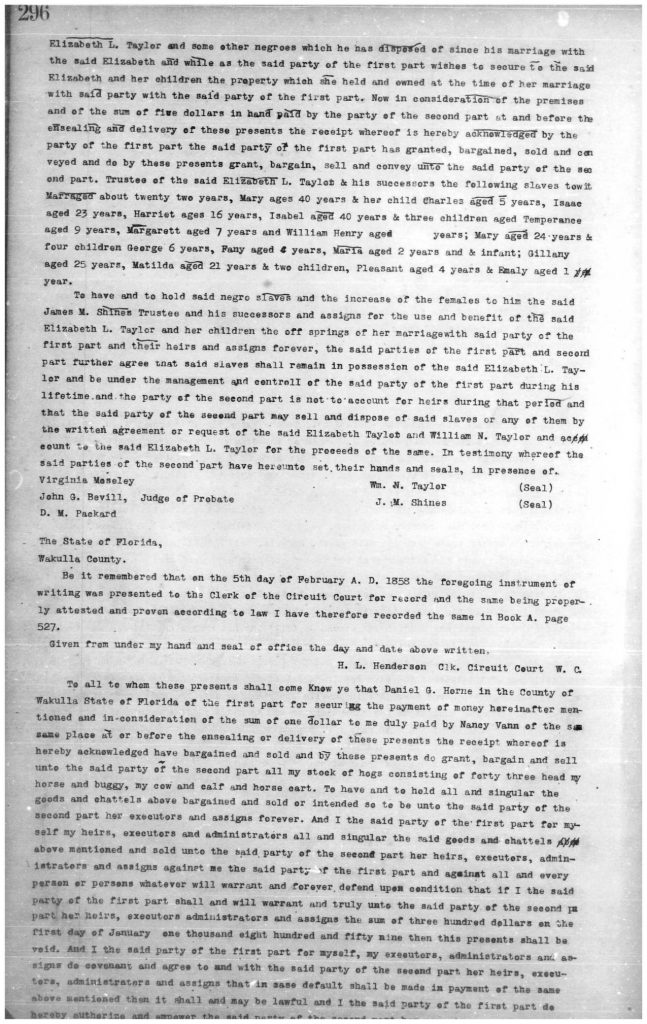

Deed between William N. Taylor and James M. Shine from Wakulla County Courthouse, Deed Records Book A-B, February 5, 1858, page 296.

From page 296:

“Trustee of the said Elizabeth L. Taylor & his successors the following slaves to wit Marr aged about twenty two years, Mary ages 40 years & her child Charles aged 5 years, Isaac aged 23 years, Harriet ages 16 years, Isabel aged 40 years & three children aged Temperance aged 9 years, Margarett aged 7 years and William Henry aged __ years; Mary aged 24 years & four children George 6 years, Fany aged 4 years, Maria aged 2 years and & infant; Gillany aged 25 years, Matilda aged 21 years & two children, Pleasant aged 4 years & Emily aged 1 year”

A number of the same individuals listed in this deed and in Elizabeth’s journal were later included in the 1860 slave schedule. The U.S. Census Slave Schedule, taken June 22, named the slaves of William N. Taylor located in Shell Point District, Wakulla County. Most of the slave schedules do not name slaves, but the census taker in Wakulla County did that year.

Under “William N. Taylor, Owner” the following slaves are listed: Allick, age 70; Isaac, age 23; Harriet, age 19; Matilda, age 21; Pleasant, age 6; Isabella, age 40; Temperance, age 13; Margaret, age 11; William, age 5; Mary, age 27; George, age 10; Fanny, age 8; Ellen, age 4; Mace, age 25; Gelaney, age 22; Charles, age 8; and June, age 11.

In 1861, the household moved to “Ridgeland,” on Lake Jackson north of Tallahassee in Leon County, and remained there until 1867. After 1867, the Taylor family moved to various locations in northern Florida, including “Woodlawn” and “Myrtle Grove” in Leon County and several locations in Madison County. At some point afterwards they moved back to Tallahassee, where they are buried.

Emancipation

It is a bit more difficult to trace the former slaves after 1865, as surnames are not given for most of them in the Taylor documents. They may also have selected new surnames. In order to find and trace emancipated slaves in extant documents, a researcher would have to work with the types of information that would have been recorded, the most useful being dates and places. For example, the 1870 population census asked for age, sex, race, occupation, and place of birth, and enumerated people by county and district. In this case, a possible clue would be the place of birth; the adults listed in the slave schedule of 1860 may have been brought from North Carolina by the Taylors. The last plantation they owned before the end of the Civil War was in Leon County, so it would be reasonable to search there for emancipated slaves. The ages given in the Taylor journal and in the slave schedule could be very helpful, although ages were not always consistent between different sources.

Case study: Lany

An unusual given name can also be key. As an example, one woman named Lany is mentioned in the journal, and there is a woman named Gelaney in the 1860 slave schedule. The 1858 bill of sale in the Wakulla County Courthouse listed “Gillany aged 25 years.” Gelaney or Gillany being an uncommon name, it is possible that a woman listed in Leon County census records in 1870, 1880, and 1885 married to Alfred Mitchell or Mitchel might be the same person as the Lany noted in the Taylor journal.

In 1870, the census taker for Leon County, Northern District listed “Delaney,” age 32, born in North Carolina as the wife of Alfred Mitchell, age 33, born in North Carolina. Also in the household is a 4-year-old named Elizabeth, an 18-year-old named Charles (possibly the child born to Mary Branson in 1853), and a 60-year-old woman named Isabella Page. Isabella was also born in North Carolina and could possibly be the same Isabella named in the 1860 slave schedule.

The same household is recognizable in the 1880 census, comprised of Alfred, his wife Gillaney, and daughter Eliza, now 14 years old.

The 1885 Florida state census finds Alfred Mitchell, his wife Laney, and his daughter Elizabeth still living in Leon County. Also in the household are Delia Ford, 20, listed as Alfred’s niece, and Laney Wilson, 8, listed as his ward.

Unfortunately, Gilaney does not appear in subsequent census enumerations. Alfred appears in the 1900 Leon County census with a wife named Lucy. One of the questions asked in 1900 was number of years married, and Alfred and Lucy had been married for 10 years. Gilaney might have died between 1885 and 1890. Eliza most likely married after 1885 and would be listed under a married name.

To continue tracing this family, a researcher could explore other resources including county courthouse records, Freedmen’s Bureau records, the records of the Freedman’s Bank, Freedmen’s Contracts when available, and the Voter Registration Rolls, 1867-1868 (digitized on Florida Memory.) For instance, a search for Lany’s husband, Alfred Mitchell, in the Voter Registration Rolls on Florida Memory returns a record of his registration to vote in Leon County on August 17, 1867. Each individual record may contain clues that lead elsewhere and a more detailed picture of a family’s lives and circumstances may emerge.

Tracing the genealogy of enslaved persons can be difficult due to the limited amount of information about enslaved persons kept in US census records prior to emancipation. When researching former slaves, don’t overlook the possibility of plantation records and other non-traditional genealogical resources. While scarce, when found they can add context and detail to information found in census and courthouse records.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Taylor Family Papers: Using Plantation Records for Researching Enslaved People." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332812.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Taylor Family Papers: Using Plantation Records for Researching Enslaved People." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332812. Accessed March 2, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, August 8). The Taylor Family Papers: Using Plantation Records for Researching Enslaved People. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332812

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program