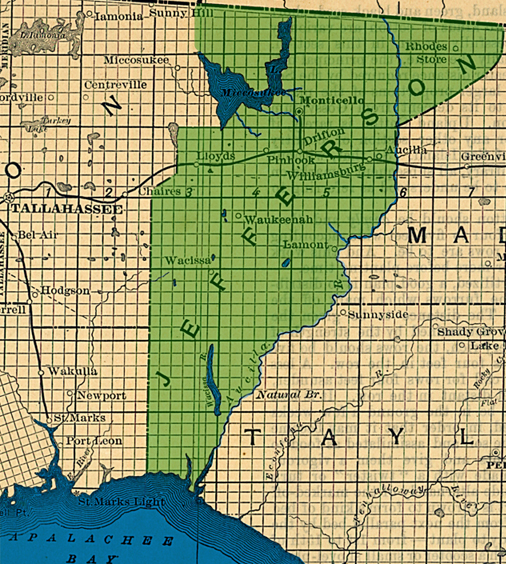

The Jefferson County Freedmen's Contracts

About These Records

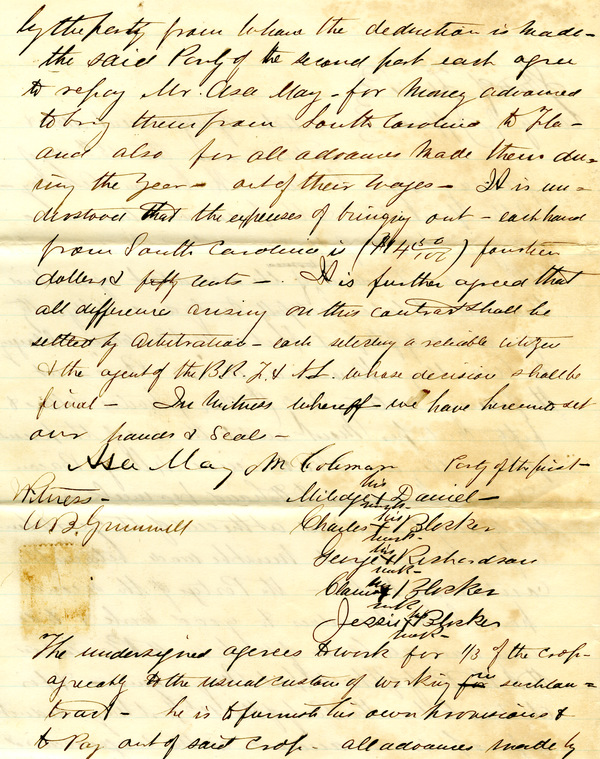

These freedmen's contracts are handwritten agreements between landowners in Jefferson County and laborers, primarily African Americans, who agreed to farm the land in exchange for a share of the crop and the means necessary to live and complete their work.

They are part of a larger collection of Jefferson County court records held by the State Archives of Florida (Series L346), which covers a broad period from the 1820s to the 1950s. The Freedmen's Bureau, established in 1865 by the United States government to assist formerly enslaved people through the difficulties attending the end of the Civil War, helped landowners and laborers write these contracts. Local Freedmen's Bureau officials also reviewed each agreement and made changes if necessary.

Generally, each contract identifies the landowner or overseer, the individuals agreeing to work the land, the kind of work to be performed, the form and amount of compensation and any additional stipulations. The level of detail in these contracts varies. In some, only the most basic conditions are explained, while in others the employer goes so far as to specify the length of the mid-day break, the foodstuffs to be provided to the laborers and even restrictions on foul language.

group of freedmen, indicating the terms of employment, the signatures of the employers, and the "X" marks of the laborers.

Background

When the Civil War drew to a close, slavery had been outlawed, but the futures of the millions of African-Americans who had labored under that system were far from certain. For the most part, the freedmen had no money, no land of their own, and the family and community ties they had relied on for a lifetime were all associated with the plantations they had previously worked on as slaves. At the same time, their former masters were also in a serious bind. They owned a tremendous quantity of land, but without the modern agricultural equipment of today it was useless without a large labor force to plant, tend, and harvest the crops.

The Freedmen's Bureau initially provided the newly liberated African-Americans with rations, medical care, and educational opportunities, but these measures were designed to be temporary. With the South's economy still almost entirely dependent on labor-intensive agriculture, former slaves and their former masters soon found themselves reuniting to fulfill their respective needs. Although under the new circumstances the freedmen were employees rather than slaves, the lack of cash for wages and lack of experience with wage labor led workers and employers to develop a very different kind of system called sharecropping. Under this arrangement, laborers did not earn a wage for their work, but instead received the basic materials they needed to live and work from the landowner whose crops they raised. At harvest time, the employees received a share of the crop, which they could then sell for cash.

Sharecropping solved the immediate problems of both landowners and former slaves, but it had serious drawbacks. Very often, a sharecropper's expenses outran the very small income he or she received from the harvest, especially since that income only came once per crop cycle. To get by between crops, sharecroppers were often forced to rely on "crop liens," essentially mortgages taken out on crops that had yet to be harvested. Like any other mortgage, it had to be paid back with interest, which frequently kept sharecroppers in a perpetual cycle of debt. Moreover, droughts, storm damage, and other factors affected the value of each year's harvest, which added another element of uncertainty to the sharecroppers' financial lives.

As time progressed, some sharecroppers were able to acquire enough tools and personal wealth to pay a flat rental fee to a landowner and farm independently rather than serve as a direct employee. This system, called tenant farming, was in many ways a step above sharecropping, but it also had its pitfalls. Ironically, although sharecropping and tenant farming encouraged their practitioners to be as productive as possible, this happened just as the demand for Southern cotton was decreasing, and higher productivity only glutted the market and drove prices further down. Although the inefficiency of the system was painfully clear, only after World War II did the South's economy become diversified enough to break away from it.

Selected Bibliography

Baker, Bruce E., and Brian Kelly, eds. After Slavery: Race, Labor, and Citizenship in the Reconstruction South. University Press of Florida, 2013.

Shofner, Jerrell H. Nor Is It Over Yet: Florida in the Era of Reconstruction, 1863-1877. University of Florida Press, 1974.

———. History of Jefferson County. Sentry Press, 1976.

Listen: The Gospel Program

Listen: The Gospel Program