Description of previous item

Description of next item

When Money Grew in Trees

Published November 11, 2018 by Florida Memory

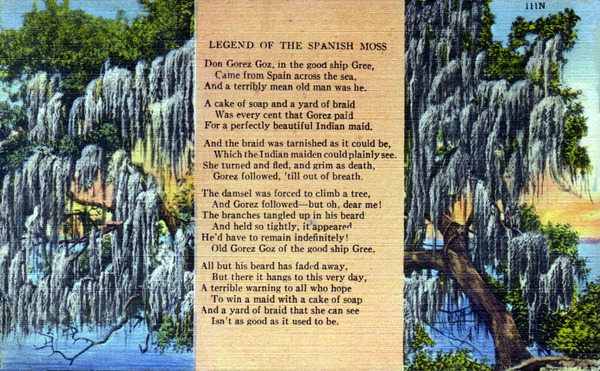

Florida wouldn’t be Florida without its beautiful oak and cypress trees. Moreover, those picturesque trees would look awfully naked without their hanging curtains of Spanish moss blowing gently in the breeze. It’s an image that has been evoked a thousand times or more in art, song, novels and poetry. The moss even has its own legend, which countless tourists have sent home on postcards for friends and loved ones to read:

But let’s get a few things straight about Spanish moss, as it is a most peculiar species. For starters, it isn’t Spanish. It’s native to North America as far north as Virginia, so the Spanish can hardly lay claim to it. To be fair, they didn’t actually mean to give their name to the moss; that was the work of their colonial rivals, the French, during the 16th and 17th centuries. French explorers jokingly called the moss “Spanish beard,” while their Spanish counterparts responded in kind by calling it “French hair.” In those days, you clearly had to get your entertainment where you could find it.

Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides) is also not actually a moss. In fact, as a bromeliad it has a closer relationship to the pineapple than it does to other species we would call “moss.” It’s an epiphyte, meaning it grows on other plants but is not parasitic. Contrary to popular belief, Spanish moss will not kill a tree if left unchecked, although it may produce enough shade to stunt its growth.

Picturesque as it may be, Spanish moss has long been known for more than just its good looks. Once its outer bark has been removed and the strong fibers inside have been allowed to dry, the resulting material is surprisingly strong, yet also soft enough to use for cushioning. Native Americans reportedly weaved dried moss into clothing, and early white settlers braided it into ropes and netting. As early as 1773, the roving naturalist William Bartram remarked during his tour of the Southeast that Spanish moss was “particularly adapted to the purpose of stuffing mattresses, chairs, saddles, collars, etc.; and for these purposes, nothing yet known equals it.” It also served as a popular curiosity and souvenir for Northern visitors. Tourists would take boxes of Spanish moss back home and hang it in their own trees, giving them a bit of Florida to enjoy until winter arrived and killed it off.

It didn’t take the enterprising people of Florida long to figure out that this natural bounty could be harvested and sold for a profit. As early as 1834, a New Englander visiting Jacksonville commented on the growing moss industry in that area. The poet Sidney Lanier, who visited Florida in the 1870s, noted a similar factory just up the St. Johns River in Tocoi. The Census Bureau listed a moss processing plant at Pensacola in a supplement to the 1880 federal census, and there was a large moss factory at Gainesville as of 1882 as well. These businesses made their money by collecting moss from local forests, curing and ginning it, and then selling it to manufacturers up north, who used the material for cushions and mattresses and other products.

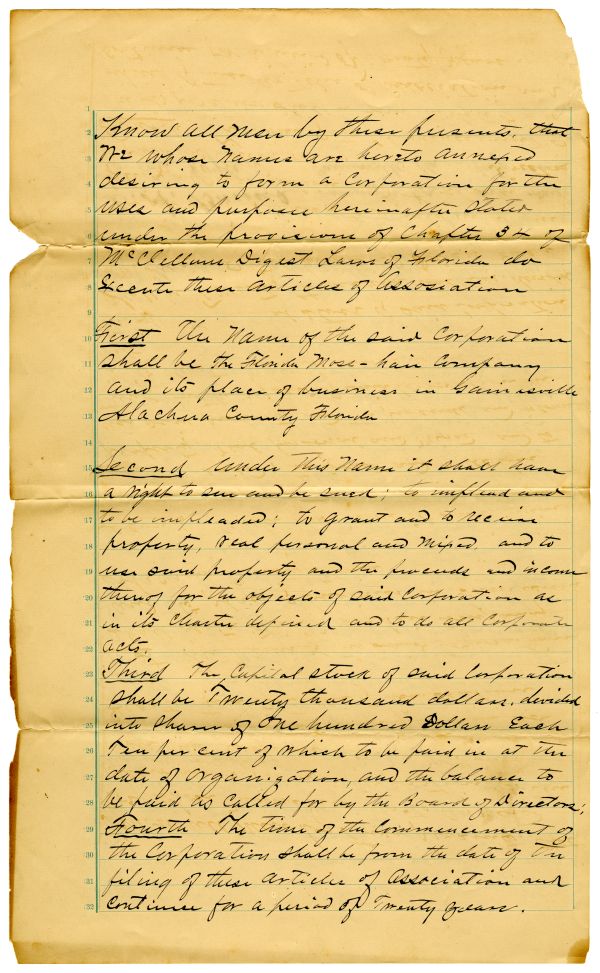

Articles of incorporation for the Florida Moss-Hair Company, based in Gainesville. From Box 192, Folder 612, Domestic Articles of Incorporation (Series S 186), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to view the entire document.

The moss business had its advantages and disadvantages. The supply was plentiful, and sometimes pecan and citrus grove operators actually paid moss collectors to rid them of the stuff, since it could decrease the trees’ production. Farm laborers often gathered moss during their off-season as a way to make extra money, gathering the material in their local woods and carting it to the nearest processing plant. The moss gatherer’s tool of choice was usually a long wooden pole with a hook or barb on one end, which could be twisted in the moss and pulled to bring it down in large clumps. From this point, however, the work was tough. The gray outer bark of the moss had to be removed to get to the strong fibers within, usually through a curing process. Moss factories sometimes did their own curing; other times they purchased pre-cured moss from their suppliers. Either way, workers would stack the moss in large piles or drop it into large trenches, and then soak the whole lot with water. This would cause the moss to rot and shed its bark. The longer the moss cured, the tougher and cleaner the inner fiber would become. Six months was required to produce the highest grade moss, which would sell at the highest price.

Spanish moss arriving at the Leesburg Moss Yard in a Ford sedan. Moss gathering was one way to earn a little extra cash back in the days when the moss industry was in full swing (photo 1946).

Once the gray outer bark of the Spanish moss slipped off easily, workers removed it from its piles or trenches and hung it out on lines to dry in the sun. Rain, wind and friction combined forces to separate the bark from the dark fibers inside. At this stage, the cured moss would either be taken to a gin or sold to another company that would process the material. Cured moss was worth about 4 to 5 cents per pound as of the late 1950s, depending on how well it had been cleaned. The unit value of the finished product is tough to determine, since government figures often combine moss with other upholstery stuffing materials. State agriculture officials in the 1950s, however, estimated the overall value of the Florida moss crop to be about $500,000 per year.

These days, inner-spring mattresses have replaced moss-stuffed ones, and synthetic materials cushion our furniture and car seats. The moss factories that once hummed with activity from Pensacola to Gainesville to Leesburg and Apopka are no more. That’s not such a bad thing, of course. The silver lining–or gray, if you please–is that now we have more beautiful Spanish moss to enjoy in the trees where nature originally put it!

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "When Money Grew in Trees." Floridiana, 2018. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/341940.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "When Money Grew in Trees." Floridiana, 2018, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/341940. Accessed February 24, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2018, November 11). When Money Grew in Trees. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/341940

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program