Description of previous item

Description of next item

The First Florida Women in Public Office

Published February 2, 2019 by Florida Memory

June 4, 2019 marked 100 years since Congress approved the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, granting women the right to vote. August 18, 2020 was the centennial anniversary of the date when enough states had ratified the proposed amendment to make it effective. We tend to focus on how these momentous events forever changed voting rights, but there’s another related victory that deserves some attention as well. Beginning in 1920, many more women began serving in public office at the state and county level, a trend that is well documented in records available from the State Archives of Florida. This article explains a bit about the history of women in public service and offers some tips on how to find the first women from your Florida community to run for election or serve in office.

First things first: 1920 wasn’t actually the start of women voting in Florida, nor was it the start of women serving in public office. By the time the 19th Amendment was ratified, several Florida communities had already granted women the right to vote in municipal elections. Fellsmere (then in St. Lucie County) was the first to do so, having put the necessary language in an amendment to its town charter, which was approved by the Legislature and signed by Governor Park Trammell on June 8, 1915. Here is the relevant clause from Section 35 of the charter (Chapter 7154, Laws of Florida):

Every registered individual, male or female, elector shall be qualified to vote at any general or special election held under this Charter to elect or recall Commissioners, and at any other special election…

Activists for women’s suffrage vowed to build on this victory, and soon other Florida towns adopted similar changes to their charters. By November 1919, a total of 16 towns in 10 counties allowed women to vote in municipal elections, including Fellsmere in what is now Indian River County; Tarpon Springs, Clearwater, Dunedin and St. Petersburg in Pinellas County; Aurantia and Cocoa in Brevard County; Orange City and DeLand in Volusia County; West Palm Beach and Delray in Palm Beach County; Florence Villa in Polk County; Miami in Dade County; Fort Lauderdale in Broward County; Moore Haven in DeSoto County; and Orlando in Orange County.

Cast from a play put on by members of the Koreshan Unity in Estero, Florida in favor of women’s suffrage. The play was titled “Women, Women, Women, Suffragettes, Yes” (ca. 1910s).

Empowered to vote, a number of women began running for public office in these towns, and in some cases they were victorious. Marian Horwitz of Moore Haven was elected mayor on July 30, 1917, the first woman to serve in that role in Florida. It was an unusual case in that it was the town’s first mayoral election since incorporating in June, and Mrs. Horwitz was directly petitioned by every single registered voter in town to accept the position. Even the two men who had earlier been competing for the nomination bowed out when her name was put forward. Mrs. Horwitz initially refused the nomination, but eventually accepted and characterized it as a way for women to take on tasks that would free up men to support the United States’ efforts in World War I. “I once felt that a woman could not measure up physically to the work of handling public affairs,” she told the press after a few days in office. “In less than a week I have changed my mind.”

But it wasn’t just municipal positions that women were filling in those days before the 19th Amendment. Many women also served in county and state positions, especially boards and commissions pertaining to issues where at that time a woman’s perspective and instincts were thought to be uniquely useful. Several women, for example, served on the state’s public school textbook selection committee, the State Board of Osteopathic Examiners and commissions in charge of planning for historic buildings and memorials. Records of commissions for court reporters and county probation officers also show a number of women in the ranks.

Page from the Secretary of State’s officer directory showing where Sarah E. Wheeler of Lakeland was commissioned as a member of the State Board of Osteopathic Examiners in 1913. Volume 12, State and County Officer Directories (Series S1284), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

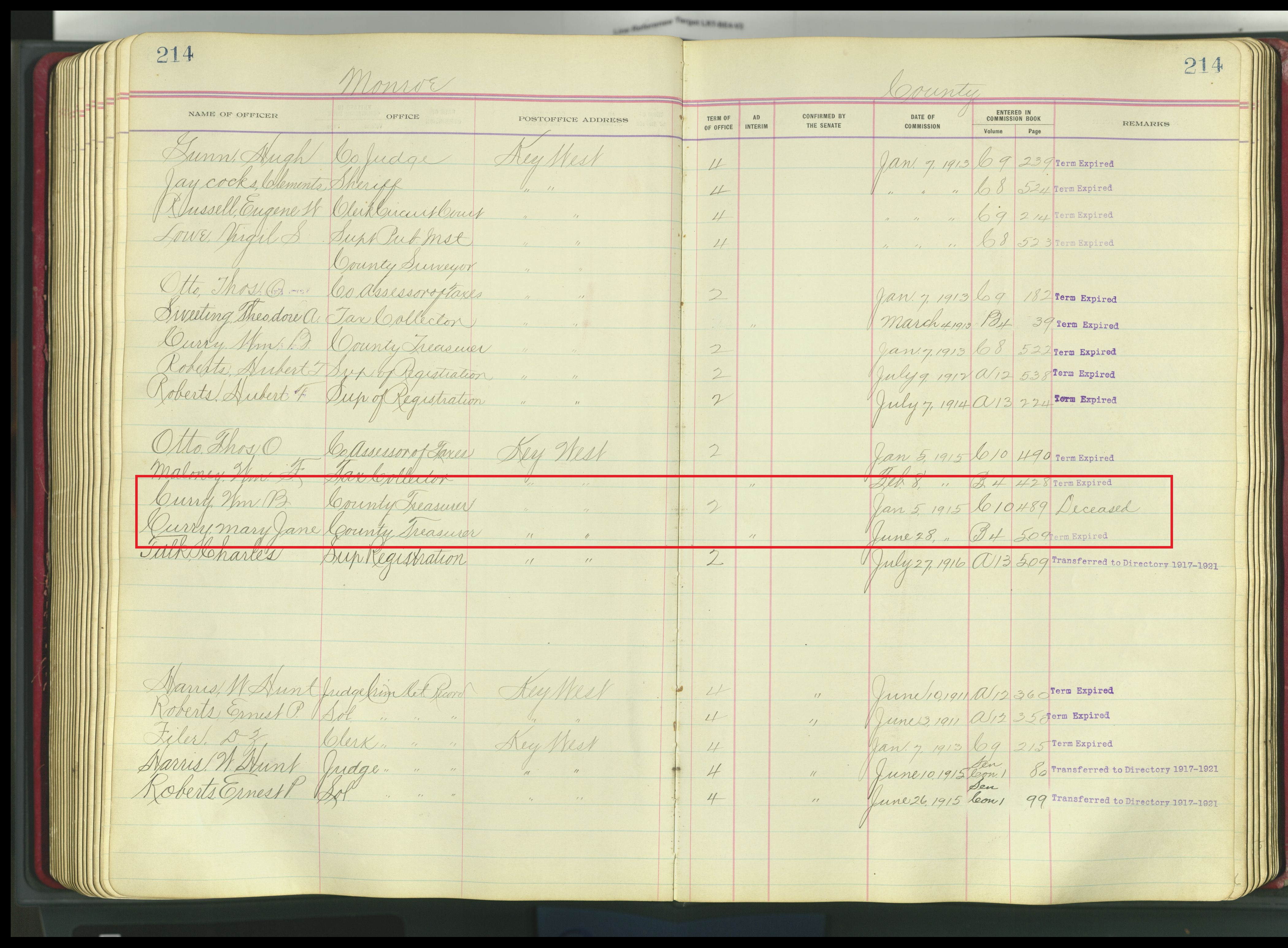

Women could also be appointed to major county offices. A common practice that lived on long after women gained the right to vote was for a woman to be appointed to complete her husband’s term in the event that he died while in office. That’s what happened in the case of Mary Jane Curry, for example, who became Monroe County’s treasurer in 1915 when her husband William died about six months into his term. Mrs. Curry was officially commissioned by the governor as her husband’s ad interim replacement, and she continued to serve until she was replaced by a newly elected successor in 1917. Other women were appointed to positions in their own right, such as Mamie Jarrell of Micanopy, who was appointed several times to the post of Marks and Brands Inspector for Alachua County.

Page from the Secretary of State’s officer directory showing appointments for both William and Mary Jane Curry as county treasurer for Monroe County in 1915. Note that the record shows William died in office, and Mary Jane was appointed shortly thereafter to succeed him. Volume 12, State and County Officer Directories (Series S1284), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

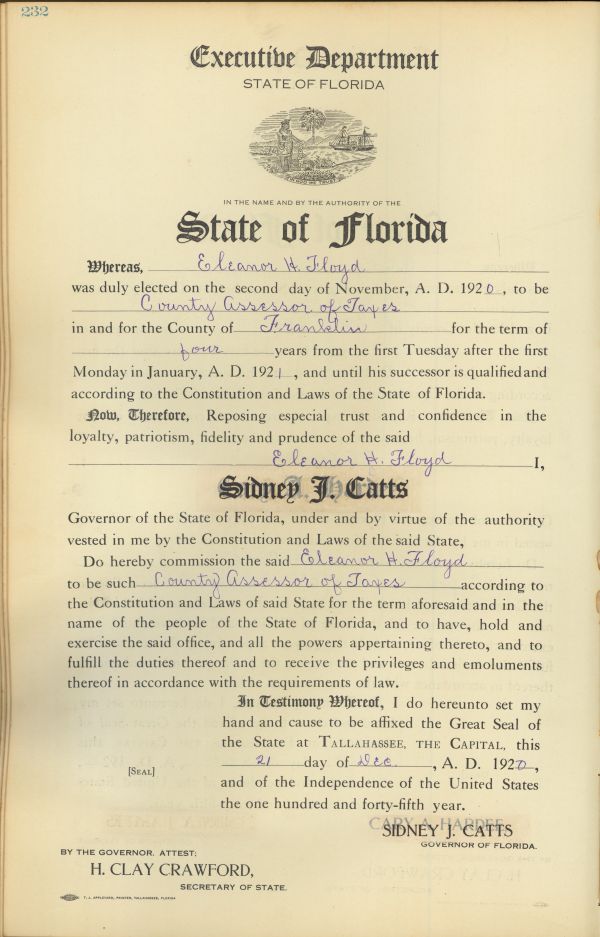

Now let’s look at how to determine who the first women were in your Florida county to serve in public office, or at least run for office. The State Archives holds records pertaining to women in both categories. First, if a woman from your county was appointed to a county or state office (like Mamie Jarrell) or elected in her own right from 1920 onward, she would have received an official commission from the governor, countersigned by the Secretary of State. The State Archives holds the record copies for many of these commissions (Series S1285, et al), as well as a set of handwritten state and county officer directories (Series S1284), which function like an index to the commissions. One way to look for early elected or appointed women from your county is to look through these directories for names of female citizens. Here’s an interesting example from the first slate of county officers appointed to serve Collier County when it was established in 1923. On the page, we see that two women were among the appointees, including Mrs. T.C. (Mamie) Barfield as Superintendent of Public Instruction and Nellie Storter as Supervisor of Registration.

Page from the Secretary of State’s officer directory showing the first officers appointed for the newly created Collier County in 1923. Two women are among the appointees. Volume 14, State and County Officer Directories (Series S1284), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

The state and county officer directories (Series S1284) are open to the public for research here at the State Archives, and our Reference Desk staff can also do a limited amount of research in the books if you have a specific person or range of years in mind. Once you find an index listing for a commission that interests you, we can determine if the State Archives also has a copy of the officeholder’s actual commission, signed oath of office or bond. See our blog post titled Researching State and County Officers for details.

Commission of Eleanor H. Floyd as tax assessor of Franklin County. Floyd was elected to the position just months after women nationwide gained the right to vote in 1920. Volume 15, State and County Officer Commissions (Series S1288), State Archives of Florida. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

The State Archives’ Florida Memory team has also recently embarked on a project to digitize the state and county officer directories from the 1820s up through 1989. Digital volunteers from across the state have been helping with this exciting and valuable project by transcribing the handwritten data to make it searchable. If you would like to learn more about how to help, even at a distance, contact the Florida Memory team at floridamemory@dos.myflorida.com.

But wait, there’s more! The state and county officer directories are helpful for finding women who were actually appointed or elected to public office, but there were many, many more who ran for election and did not win their races. Luckily, even their candidacy can be documented using records available here at the State Archives.

After each primary and general election, a canvassing board for each county writes up an official report showing the names of the candidates who were on the ballot for each office and how many votes they each received. This report is then forwarded to the Secretary of State, who retains the election results and lets the governor know who to commission for each office. The State Archives holds a virtually complete set of these reports dating back to 1865. You can look through these canvassing reports to see not only who was elected to each public office, but also all of the candidates who ran against the winner and lost. This would be a useful tactic if you wanted to find the first women in your county to run for local office, regardless of whether they won or lost. Here’s an excerpt, for example, from the canvassing report for Palm Beach County for the general election of 1920, the first in which all women in the state had the right to vote. Agnes Ballard, who incidentally was Florida’s first registered female architect, is shown winning the race for Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Excerpt of a page from the 1920 general election canvassing report for Palm Beach County. Agnes Ballard is shown as having received the largest number of votes for the office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Volume 22, Canvassing Reports (Series S1258), State Archives of Florida.

The canvassing reports (Series S1258) are grouped into volumes by election year and then by county. They are open to the public for research here at the State Archives. You can also contact the Reference Desk if you have questions about a specific race or if you are looking for a specific person.

With the anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment upon us, now is an excellent time to do some research on the women in your county who have run for and served in public office. Take advantage of the resources available to you here at the State Archives, and let us know how we can help.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "The First Florida Women in Public Office." Floridiana, 2019. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342052.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "The First Florida Women in Public Office." Floridiana, 2019, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342052. Accessed February 24, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2019, February 2). The First Florida Women in Public Office. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/342052

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program