Description of previous item

Description of next item

Beachification

Published June 6, 2020 by Florida Memory

When someone in Nebraska or Maine or Michigan thinks about Florida, what do they picture in their mind? Admittedly we didn’t take the time to do a study, but it’s safe to assume that if we had, “beaches” would be close to the top of the list. Florida is globally famous for its miles and miles of gorgeous beaches, as well as beachy-sounding communities like Ormond Beach, Riviera Beach, Palm Beach, Vero Beach and Fort Walton Beach. It’s funny, though: if you look back at the history of these towns, many of them didn’t start out with the word “beach” in their names at all. The original names were often a homage to some other aspect of the communities’ identity, and it took the enterprising vision of real estate developers or chambers of commerce to get the word “beach” in there. In a word, you might call this process “beachification.”

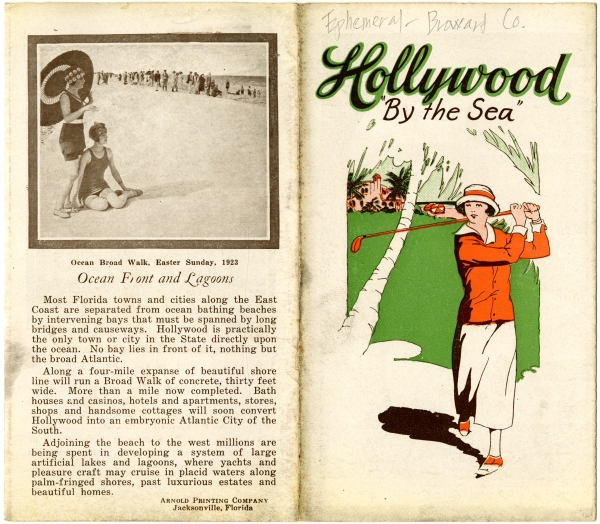

The earliest examples of beachification ironically didn’t use the word “beach.” In the late 1800s and early 1900s when hoteliers and railway companies were really starting to promote Florida to northern tourists, they had to do it without many of the advertising tools we see today like film, radio, television, or in some cases even color brochures. In the absence of good visuals, promoters used the written word to let their readers paint pictures of Florida for themselves. Writers used every sumptuous word in their arsenal to sell Florida to would-be visitors, and it quickly became apparent that some place names had a better ring than others when it came to luring tourists. One favorite trick was to attach “by-the-Sea” or something similar to a place name to give it some flair and ensure there was no confusion about where a certain town was located. Lanark-on-the-Gulf, Ormond-by-the-Sea, Hollywood-by-the-Sea, and Wilbur-by-the-Sea are just a few of the new place names that emerged from that trend.

Putting that little geographic reminder in the name of a town made for cute postcards and advertisements, but in practice it was a bit out of step with reality. People didn’t typically say, “Let’s drive over to Ormond-by-the-Sea tomorrow to watch the races on the beach” or “You know you have to go through Lanark-on-the-Gulf to get to Carrabelle.” It was simply too cumbersome to be conversational, and writing the extra words wasn’t exactly a day at the beach either. So, over time, many of the seaside cues were dropped, although a few are still around, like Lauderdale-by-the-Sea.

Another round of beachification came with the Florida Boom, those heady years in the early 1920s when land could go on sale at breakfast and be sold ten times by dinnertime, particularly on the Atlantic coast in South Florida. Speculators and real estate investors were buying thousands of coastal acres and drawing up elaborate plans to build entire new resort cities out of the sand. They weren’t building in a vacuum, however. Many coastal settlements already existed and were thriving thanks to good farmland, Henry Flagler’s Florida East Coast Railway and the Dixie Highway. From a developer’s perspective, these towns might have been off to a good start, but a little strategic rebranding couldn’t hurt.

A load of visitors and potential land buyers tour real estate in Hialeah near Miami. Developers used free trips, colorful advertising and entertainment to lure new residents and investors (1921).

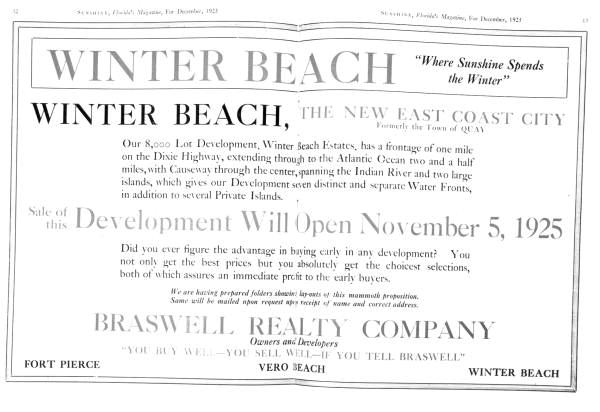

The quaint town of Quay in present-day Indian River County is a good example. Quay started out with the name Woodley in 1894 when Flagler’s railroad came through the area, but in 1902 the town was renamed in honor of Senator Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania, who owned a home nearby. When the Florida Boom came along, Quay’s frontage on the Atlantic and Indian River caught the attention of Charles C. Braswell, a local developer. He and his investors quickly bought up a large chunk of the surrounding land and subdivided it into 8,000 lots, including some on islands out in the Indian River. By the time this “new East Coast city” went on sale in November 1925, Braswell had convinced the locals to rename it “Winter Beach.” Much like Winter Garden and Winter Haven, the idea was to attract visitors and residents from up north who were ready for a break from the cold winter weather. In case the name wasn’t enough, Braswell advertised his new development with the slogan, “Where Sunshine Spends the Winter.”

Advertisement for Charles C. Braswell’s Winter Beach development in present-day Indian River County (1925).

New Smyrna Beach, located up the coast in Volusia County, had a similar experience, only with a much longer history. New Smyrna started out as a plantation established by Scottish physician Andrew Turnbull during the brief period when Florida was a colony of Great Britain in the 1700s. Turnbull received a 40,000-acre land grant from the British government and then proceeded to recruit a labor force to manage it, drawing most of his workers from the island of Menorca. Most of the laborers were indentured servants rather than enslaved persons, but relations between them and Turnbull’s overseers soured in 1777 and many of them ended up leaving the plantation altogether.

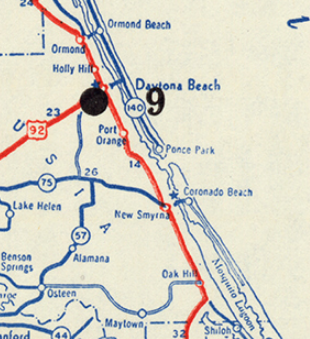

Turnbull had named his enterprise New Smyrna after the Turkish port of Smyrna, where his wife had been born and he himself had served as a British consul. Even after the plantation failed, the name New Smyrna survived. A post office was established there in 1869, and a town was incorporated in 1887. Originally, New Smyrna referred to the town itself on the west side of the Indian River, while the portion of the settlement on the other side developed its own identity under a different name, Coronado Beach. As Florida grew and its popularity rested more and more on its coastal vistas, New Smyrna leaders began looking for ways to zing up the town’s image. They briefly considered dropping the word “New” and just calling the town Smyrna, but that didn’t get very far. As the Orlando Sentinel put it at the time, the “New” appellation stood for the town’s long history and connections to the Old World. Why mess with that? The next year, the city decided to keep its historic name but attach the word “Beach” to highlight one of its greatest selling points. About ten years later, New Smyrna Beach annexed the town of Coronado Beach, and now New Smyrna Beach is one of the most popular areas in Volusia County for visitors.

The New Smyrna-Coronado Beach pattern of beachification was repeated in a few other cases as well. Sometimes the coastal portions of a settlement would incorporate separately from the inland town because they were geographically set apart by an inland waterway, or because their business patterns and interests were so different. Daytona and Daytona Beach, Fernandina and Fernandina Beach, Pompano and Pompano Beach and several other pairs of municipalities all used to be separate entities before consolidating in the mid-20th century. These unions often took some negotiation, but everyone involved usually emerged with some new advantages. The coastal residents gained access to vital utility systems and inland facilities, while the inland municipalities won that valuable “beach” buzzword for the ends of their names.

Excerpt of a 1946 state road map showing New Smyrna and Coronado Beach and Ormond and Ormond Beach as separate municipalities. The Ormond split is a slight misnomer; the 1929 legislative act creating the separate town of Ormond Beach never took full effect because it was contingent on a referendum that failed. The voters chose not to incorporate a separate town of Ormond Beach, but it still ended up on some maps. The town of Ormond finally settled the matter by changing its name to Ormond Beach in 1950. Click or tap the image to view a zoomable version of the complete map.

Have questions about when or how a particular Florida town was established? Contact the State Archives reference desk with your question! In addition to having the exact dates for many of these events, we also hold the original signed copies of the laws establishing each of Florida’s many towns and cities. Those might come in handy if you’re doing research for a local history display or other project. Our reference staff may be reached at 850.245.6719 or at Archives@dos.myflorida.com.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Beachification." Floridiana, 2020. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/345506.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Beachification." Floridiana, 2020, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/345506. Accessed February 19, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2020, June 6). Beachification. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/345506

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program