Roots of the Civil Rights Movement in Florida

The modern civil rights movement is often said to have begun in 1954 with the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Supreme Court decision and ended with the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968. However, the movement has deep roots in a much longer history of struggle and activism.

Individuals of African descent have been in Florida since the days of the Spanish conquistadors. When Juan Ponce de Leon first arrived in Florida in 1513, his crew included black members.

In Spanish Florida, the law recognized slaves as people who had legal rights and could own property. Under Spanish law, slaves could purchase their freedom and attain the rights of all the king’s free subjects.

Until 1821, the line between Florida and Georgia was an international boundary. Florida was a Spanish colony, while Georgia was a British colony. After the American Revolution (1776-1781), Georgia became a part of the United States, but Florida remained a Spanish colony.

Black men and women from Georgia and farther north often crossed the border into Florida to escape slavery. Some of these people chose to live with the Seminole Indians. Others lived among the Spanish as free blacks. In 1693, King Charles II of Spain granted the escaped slaves living in Florida their freedom as long as they converted to Catholicism and joined the militia.

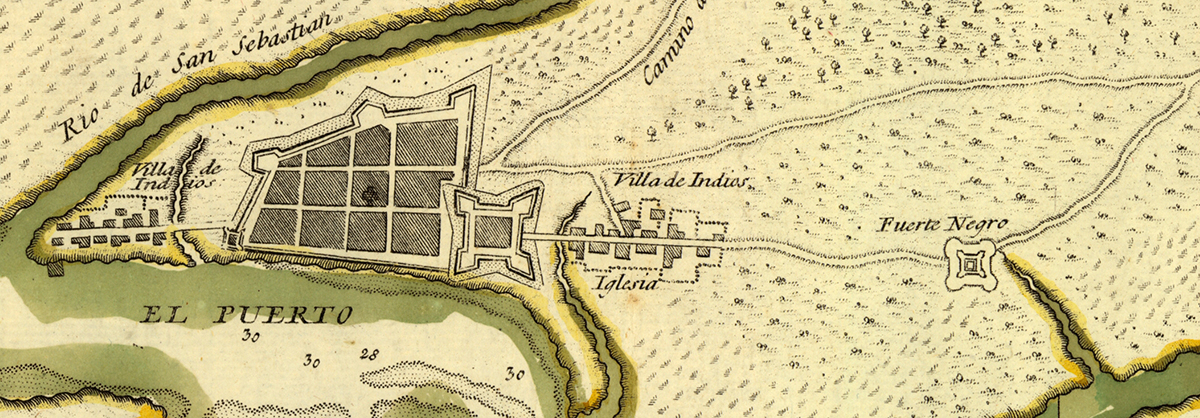

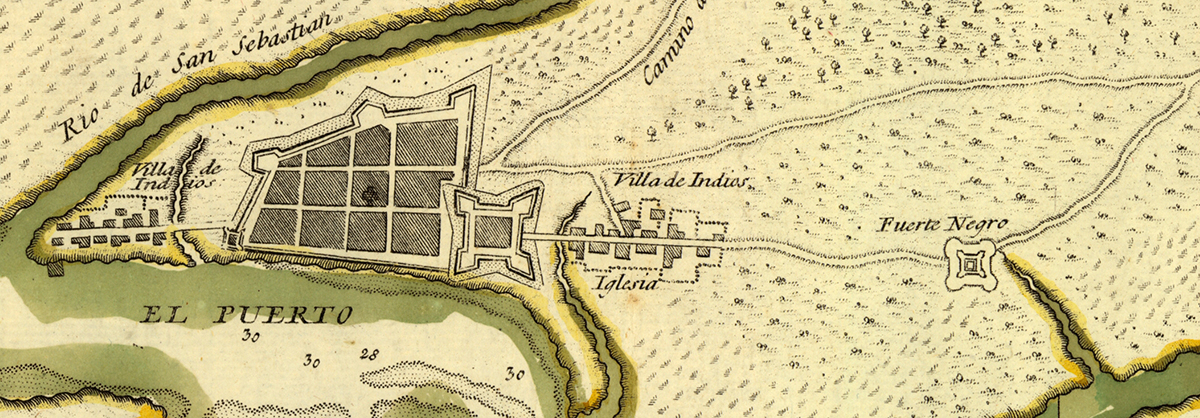

1783 map depicting St. Augustine and Fort Mose (Fuerte Negro) as they appeared in 1740.

In 1821, Spain and the United States signed the Adams-Onis Treaty, which transferred Florida to the U.S. The treaty guaranteed United States citizenship to the Spanish individuals who stayed in Florida. However, the laws and practices of the United States were very dangerous for free blacks. Many of the free black Spanish inhabitants chose to go to Cuba or the Bahamas rather than risk being re-enslaved.

Once Florida became a United States territory, settlers from Georgia, Alabama and the Carolinas began migrating into the area. Many of the newcomers brought slaves with them, along with the rules and customs that governed slavery in other states. Florida’s territorial legislature began passing its own laws concerning slavery in 1824. By the time the Civil War broke out, very few free blacks were left in Florida.

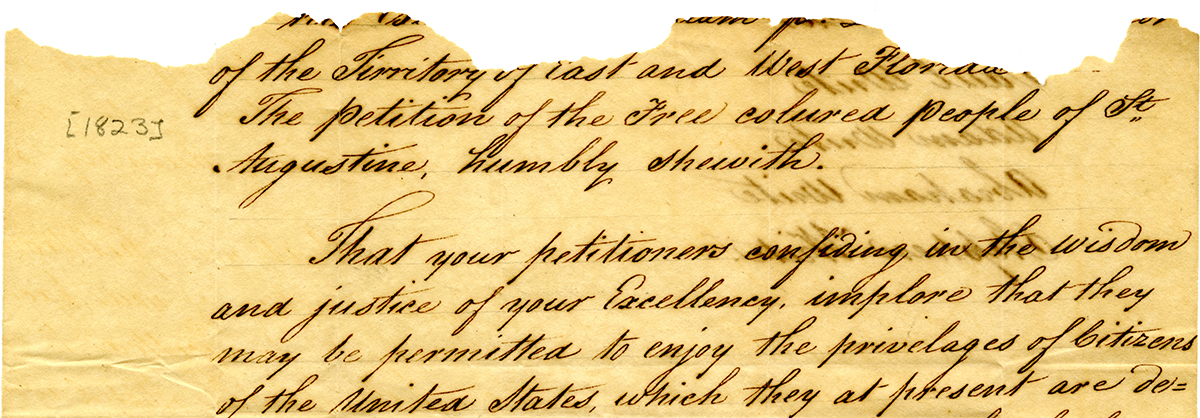

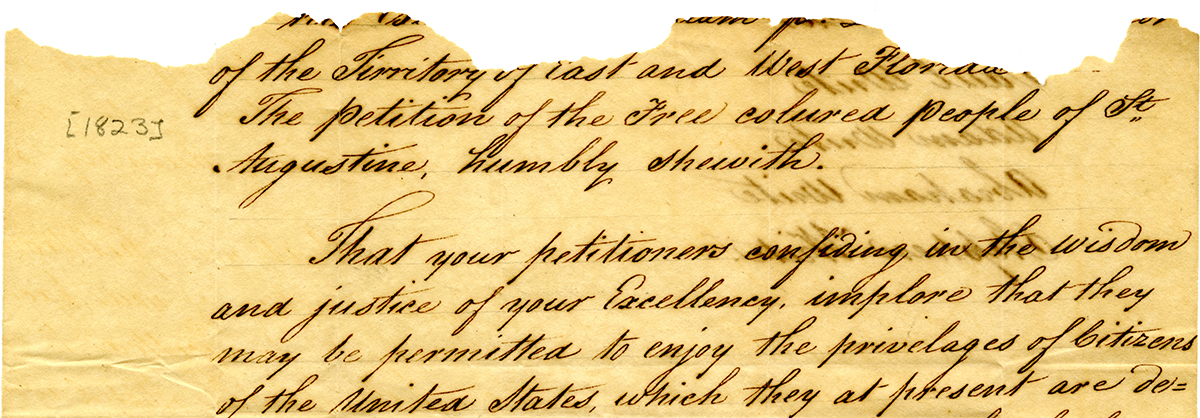

This petition was written to the Territorial Legislative Council in 1823 by the "free coloured people of St. Augustine" requesting that they be allowed to continue walking the streets and gathering together after the hour of 9:00 after they were prohibited from doing so "by the Corporation of this City."

The Union victory in the Civil War (1861-1865) ended slavery in the United States. The Union military occupied the Southern states until they complied with Congress’ requirements for readmission to the U.S. To rejoin the Union, Florida had to register all of its eligible voters, including blacks, and approve a new state constitution that acknowledged the end of slavery and the right to equal protection under the law without regard to race or color. Florida was officially readmitted to the United States on June 25, 1868.

Thousands of African-American men voted in Florida for the first time and participated in the state’s political system. Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs became Florida’s first black secretary of state in 1868. Josiah Thomas Walls became Florida’s first black congressman, taking office in 1871.

In the early years of Reconstruction, Florida’s state and local governments were controlled by the Republicans, the same party that had acted in Congress to force the Confederate states to write new state constitutions acknowledging the end of slavery. Backed by African-Americans and supportive whites, the Republicans attempted to ensure political and social equality for freedmen.

An 1873 law declared that no Florida citizen could be denied “full and equal enjoyment” of any theater, inn, railroad or place of amusement. Over time, however, voter intimidation and accusations of corruption eroded the Republicans’ base of support.

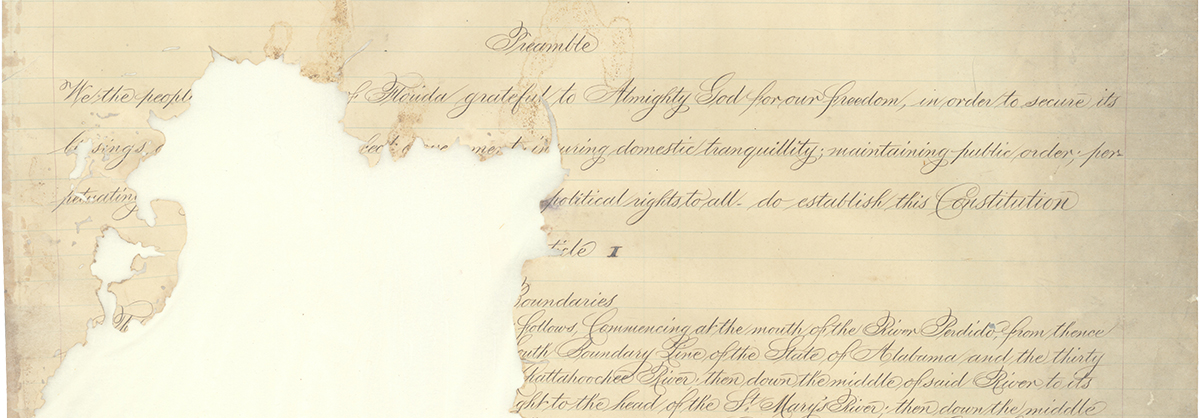

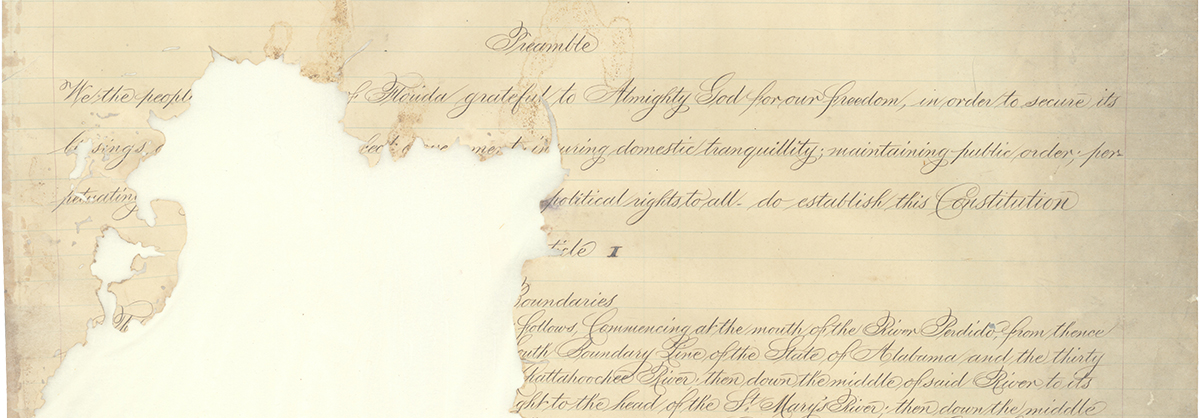

The Reconstruction constitution returned civilian control of the state. It enfranchised black males and required each voter to take an oath of loyalty to the State of Florida and the United States Government.

The presidential race of 1876 was one of the most controversial in American history. Three Southern states, including Florida, were unable to declare a winner. To settle the outcome of the election, the Democrats agreed to support the presidency of the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes. In exchange, the Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South.

In Florida, the race for governor was also contested, but the Florida Supreme Court eventually decided the Democratic candidate, George Franklin Drew, was the winner. With federal troops out of the South and the Democratic party in control in Tallahassee, Reconstruction was over in Florida.

With the Republicans out of office, the rights that African-Americans obtained during Reconstruction began to erode. Florida’s 1885 constitution legitimized poll taxes as a prerequisite for voting, which disproportionately disenfranchised African-Americans and many poor whites who couldn’t afford to pay the tax.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 declared segregation legal as long as public facilities for blacks and whites were “separate but equal.”

The laws that mandated segregation of public places were known as “Jim Crow” laws. These laws kept black citizens from using the same facilities as whites. Public schools, transportation systems, beaches, restrooms and drinking fountains were segregated. Facilities for blacks were usually inferior to those for whites, if they were available at all.

Some African-American leaders contested restrictive laws in the courts and boycotted segregated businesses. Others focused on expanding social services and educational opportunities for black Floridians. Prominent African-Americans such as Mary McLeod Bethune, James Weldon Johnson and A. Philip Randolph became spokespersons for this movement.

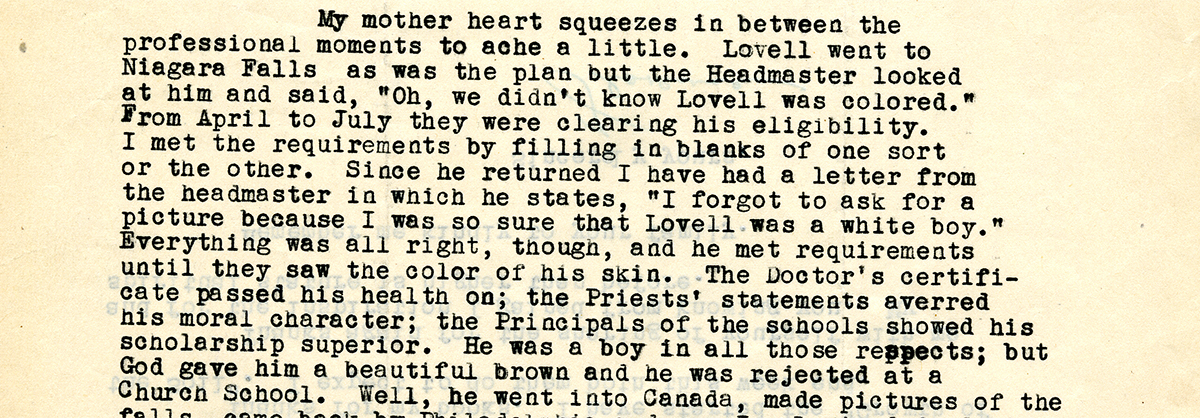

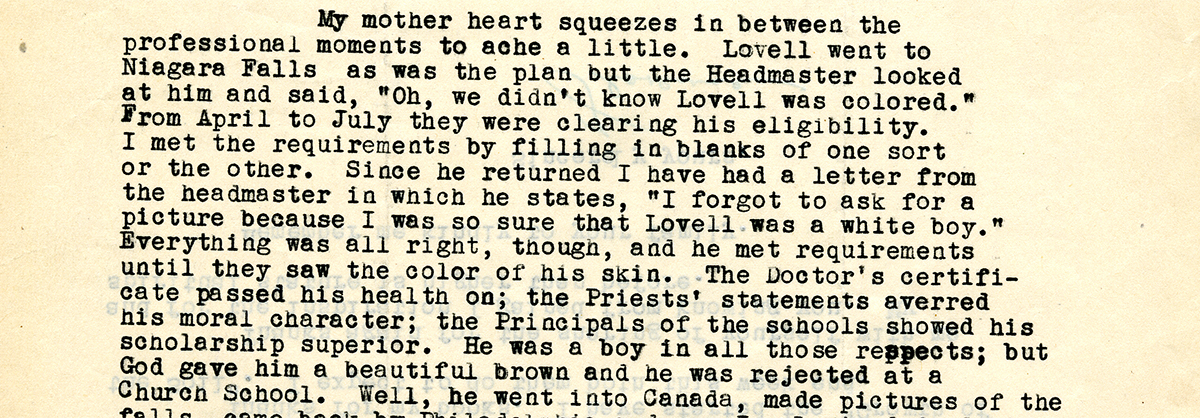

The author of the letter, Florence Lovell Roane, was a professor of English at Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona. Her son Lovell was accepted to a college preparatory school in Niagara Falls, New York. When he arrived, he was denied admittance on account of his race.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, the government called on citizens to join the fight against tyranny and oppression overseas. Many African-Americans served in the armed forces, even while the military and much of the country remained segregated.

Black leaders hoped that the sacrifices of African-American soldiers in the United States’ war against fascism and tyranny abroad would also serve to defeat racial prejudice and discrimination at home. This idea was called the “Double V Victory.”

A. Philip Randolph and Mary McLeod Bethune worked to end discrimination in the military and defense industries. In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 which prohibited racial discrimination in defense industries. After the end of World War II, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981 calling for equal treatment in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin. These were limited victories, however.

Even after President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, defense industry employers still generally hired African-Americans only for low-paying, unskilled labor. Furthermore, neither Executive Order 8802 nor Executive Order 9981 did much to combat ongoing segregation in public facilities and businesses outside the military and defense industries.

1954-1968: The Struggle to End Legal Discrimination

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously decided in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas that school segregation was unconstitutional. The effects of this ruling went far beyond just the schools. Protestors began challenging legal segregation in buses, stores, theaters, beaches and other public places.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white passenger. Her actions led to the Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama.

Five month later, two Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU) students took action in Tallahassee, Florida. Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson sat down in the “whites only” section of a city bus. When they refused to move, the bus driver called the police. In the days immediately following the arrests, students at FAMU organized a campus-wide boycott of city buses. Soon, news of the boycott spread throughout the city. Reverend C.K. Steele, pastor at the Bethel Baptist Church, led the boycott of the city-run bus system. After a seven-month standoff, the city finally ended segregation on its buses.

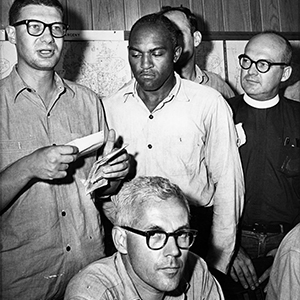

Tallahassee witnessed several sit-ins in the early 1960s at prominent businesses that maintained “whites only” lunch counters. The first sit-in in Florida’s capital city took place on February 13, 1960. On February 20, students from Florida A&M University and others from around the country held a sit-in at the Woolworth lunch counter in downtown Tallahassee. When they refused to leave, 11 were arrested and charged with “disturbing the peace by engaging in riotous conduct and assembly to the disturbance of the public tranquility.”

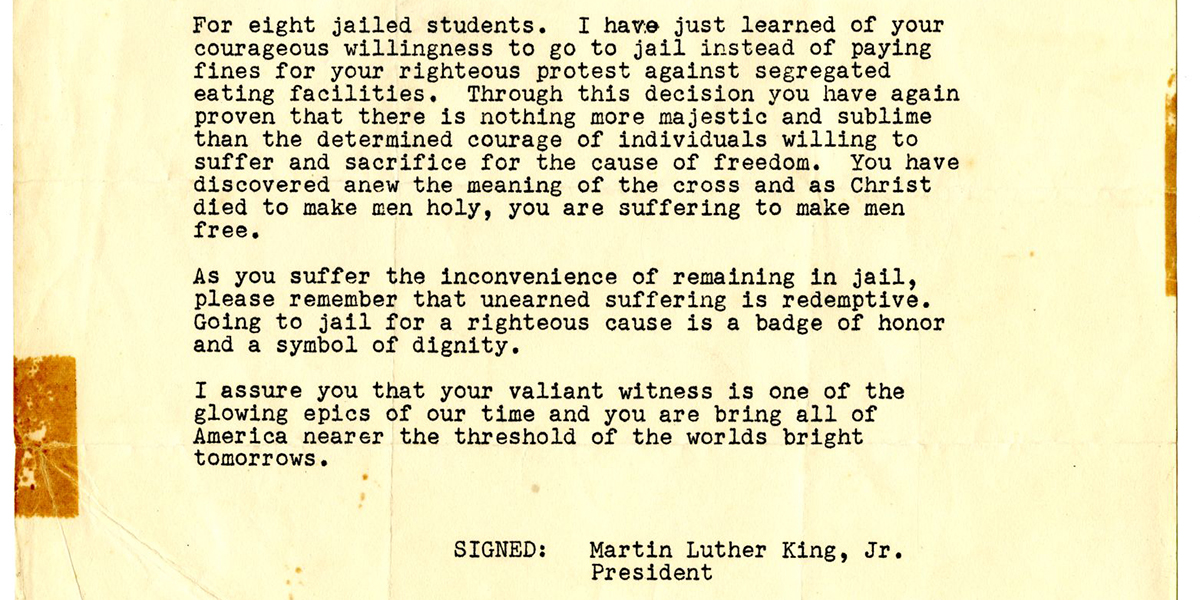

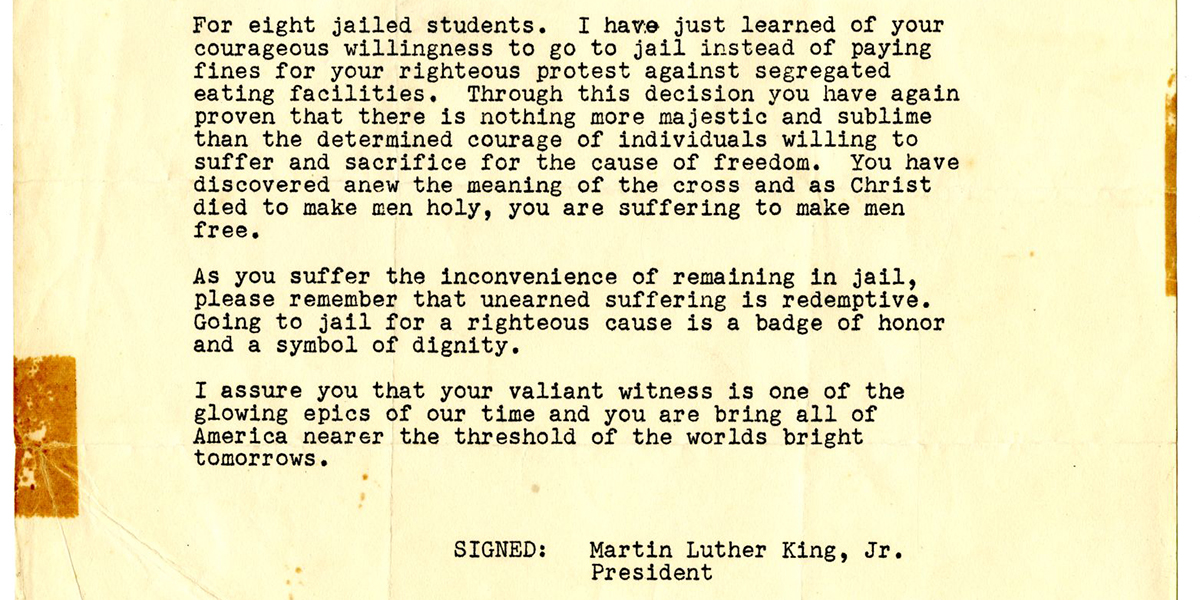

Rather than pay their fines, eight students opted for jail time, effectively launching one of the first jail-ins of the civil rights movement. Among those jailed were Patricia Stephens and her sister Priscilla. In the weeks that followed, additional demonstrations took place at the same Woolworth and also at McCrory’s department store.

While imprisoned, Patricia wrote a letter about her experience and her thoughts on civil rights, which reached leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Jackie Robinson. King wrote back to Stephens: “…you are suffering to make men free.”

Copy of a telegram from Martin Luther King Jr. to C.K. Steele, March 19, 1960.

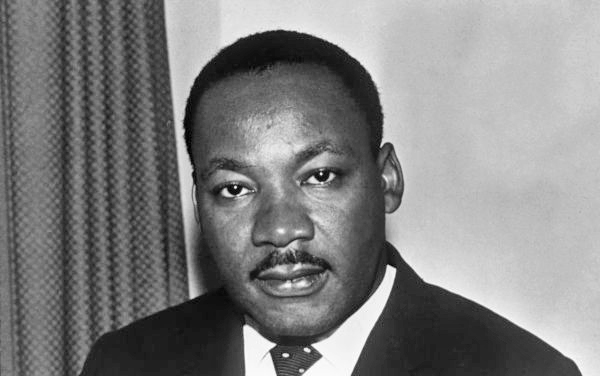

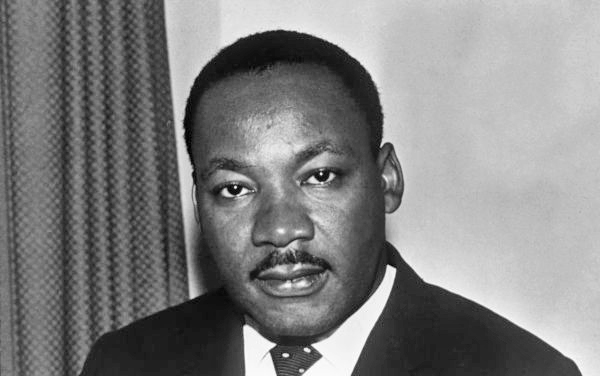

St. Augustine became a major battleground in the civil rights movement during the summer of 1964. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other prominent civil rights leaders came to lend their support.

On June 18, 1964, white and black protesters staged a wade-in at the pool of the Monson Motor Lodge. The owner of the hotel responded by pouring a jug of acid into the water near their heads. Pictures of the terrified swimmers were published in newspapers around the world.

The U.S. Congress was debating civil rights legislation at that time, and the St. Augustine situation helped influence many lawmakers to vote in favor of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law on July 2, 1964. The Act outlawed employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, required equal access to public places and employment, and enforced desegregation of schools and the right to vote.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., came to St. Augustine in 1964 to protest segregation.

In 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s voting campaign in Selma, Alabama. The marchers sought to address voter suppression tactics by local government that prevented many African-Americans from registering to vote.

During their peaceful march on March 7, 1965, protesters were brutally attacked by state troopers. This day became known as “Bloody Sunday.” In reaction to televised footage of the tragedy, public support for voting reform increased. President Johnson and Congress passed the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Act removed barriers at the state and local levels that prevented African-Americans from exercising their right to vote.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. King had travelled to Memphis to support the sanitation workers’ strike for better wages and safer working conditions.

The tragedy of King’s assassination provided added motivation to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which had been stalled in Congress. Also known as the Fair Housing Act, the bill prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental and financing of housing based on race, religion or national origin. It was signed into law on April 11, 1968.

The modern civil rights movement is often said to have begun in 1954 with the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision and ended with the death of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. However, the movement has deep roots in a much longer history of struggle and activism. Similarly, while King’s death marked a turning point in civil rights activism, it was far from being the end. Just as the struggle for civil rights began decades before the most celebrated marches, boycotts and moments of triumph, its example left an enduring legacy of aspiration and progress toward freedom for all Americans that continues to this day.

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program