Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously decided that school segregation was unconstitutional. Although the court insisted schools integrage “with all deliberate speed,” the actual process of school desegregation continued into the early 1970s.

At the same time, political protests and civic engagement led to gradual changes to discriminatory laws. Florida's towns and cities slowly integrated buses, stores, theaters, beaches and other public places.

Tallahassee Democrat headline on desegregation ruling, 1954

A mother escorts her two daughters to Orchard Villa School, 1959

Jan and Irene Glover, ages nine and seven, walk with their mother, Irvena Prymus, to Orchard Villa School in Liberty City, Florida. Prymus was a Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) member.

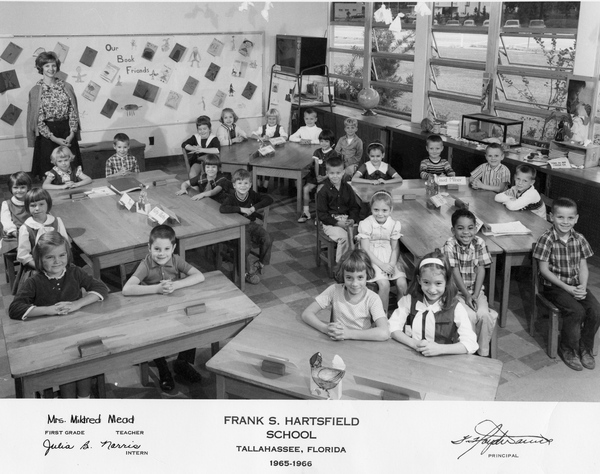

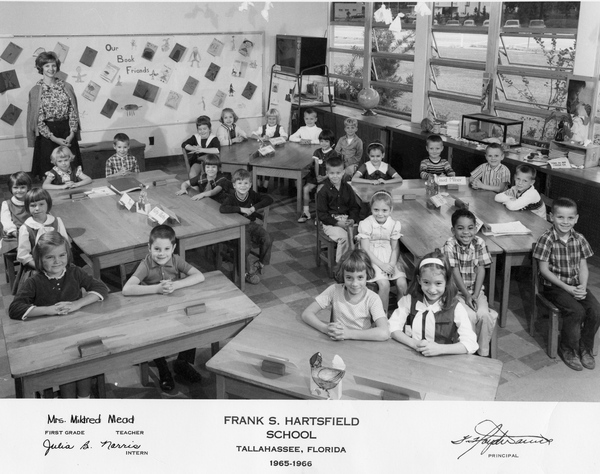

1965-1966 class portrait at Frank S. Hartsfield School

Steven Partridge was one of the first African-American students at Hartsfield Elementary School in Tallahassee.

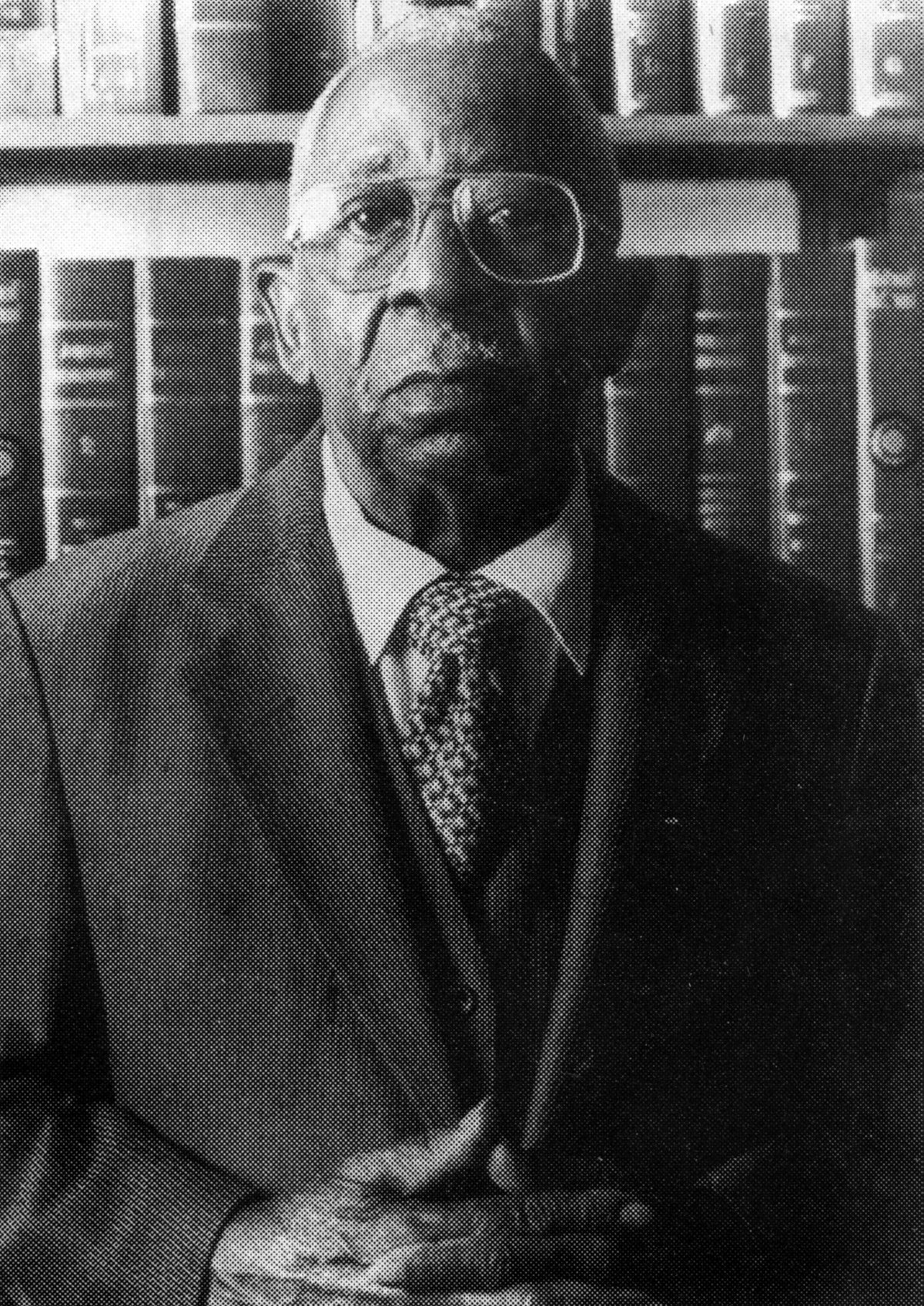

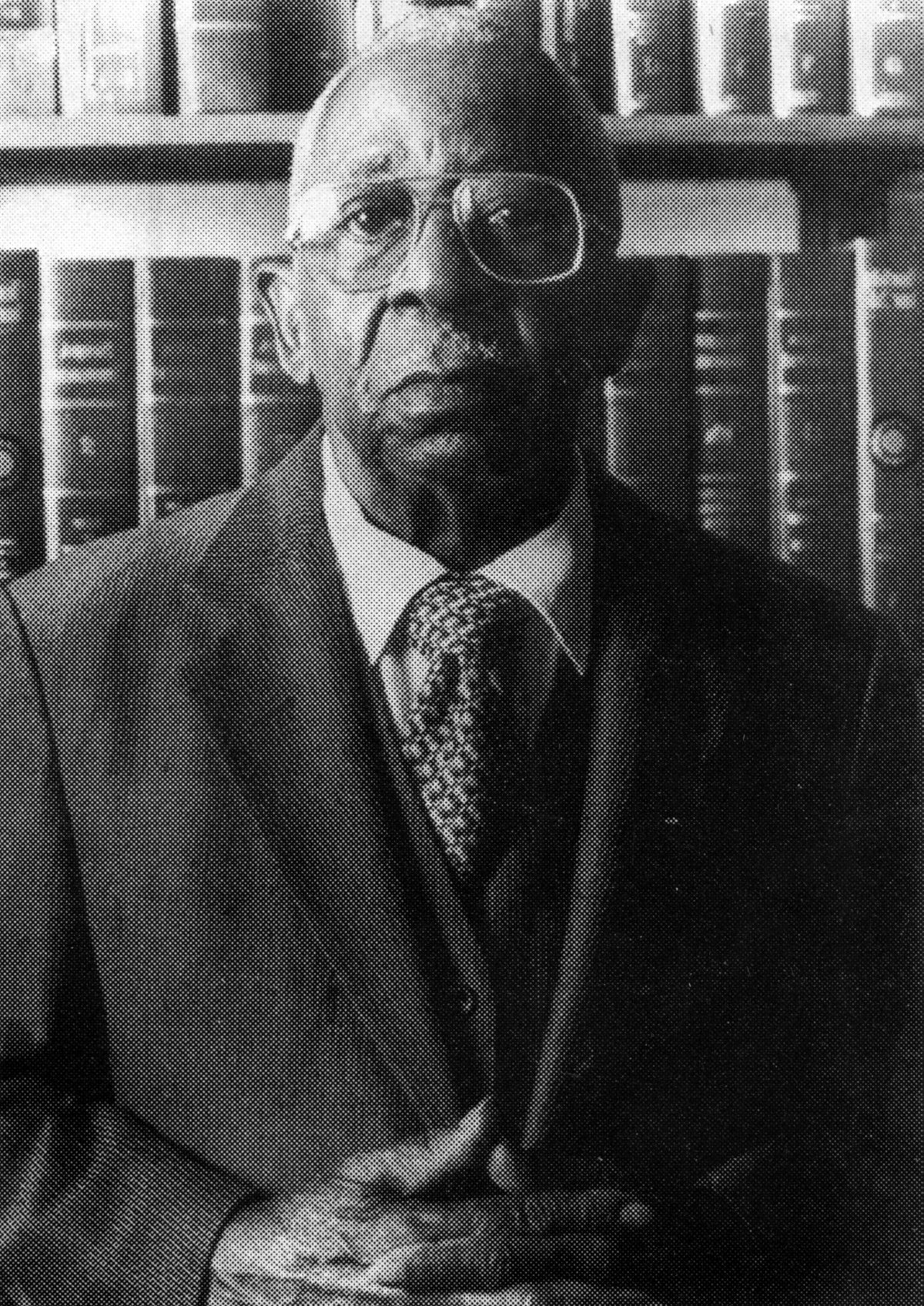

Virgil Darnell Hawkins, ca. 1975

Virgil Hawkins was a graduate of Bethune-Cookman College. In 1946, Hawkins applied for admission to the University of Florida College of Law. He was denied admission on the basis of race. Although Hawkins was never admitted to the University of Florida, his battle eventually led to the integration of Florida's graduate and professional schools.

Tallahassee Bus Boycott

African-American men and women in Tallahassee boycotted the bus system for nearly seven months after two Florida A&M University (FAMU) students were arrested for sitting beside a white woman on a segregated city bus. During the boycott, protestors carpooled to get to and from work and for other necessary transportation. Twenty-one members of the Inter-Civic Council were convicted on charges of operating an illegal transportation system for arranging the car pool without a franchise.

Reverend C.K. Steele, pastor at Bethel Baptist Church, led the boycott of the city-run bus system. The boycott lasted primarily from May to December of 1956. According to Tallahassee historians Mary Louise Ellis and William Warren Rogers, “City commissioners and protesting blacks never achieved a formal settlement, but gradually the sight of blacks riding at the front of the bus became more common, and the battle moved to another front.”

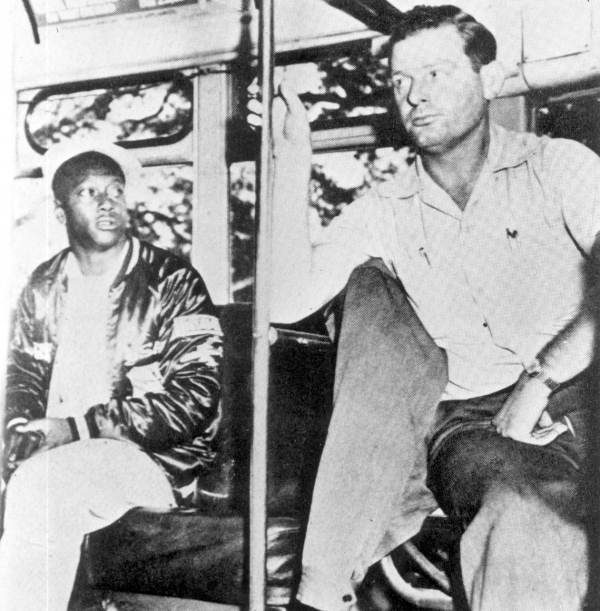

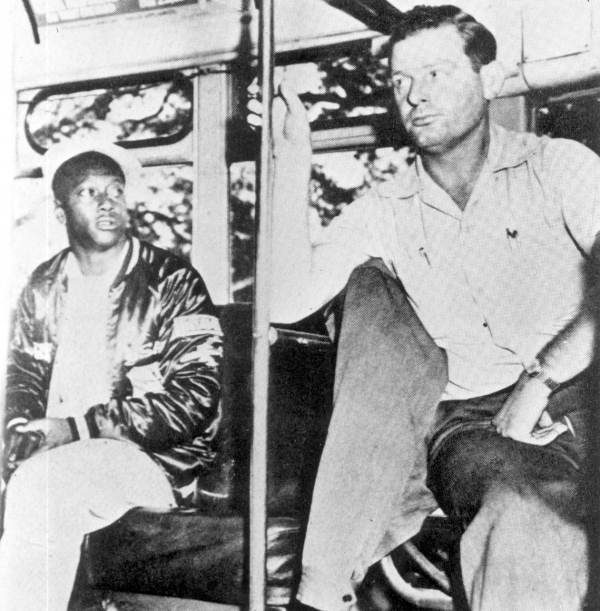

Morris Thomas defying segregated bus seating in Tallahassee, 1956

Morris Thomas refused this Tallahassee bus driver's request to move to the back of the bus, December 27, 1956. Thomas lived in Midway, Florida, but was home on leave from the Navy. He heard about a possible demonstration, but did not know it had been called off.

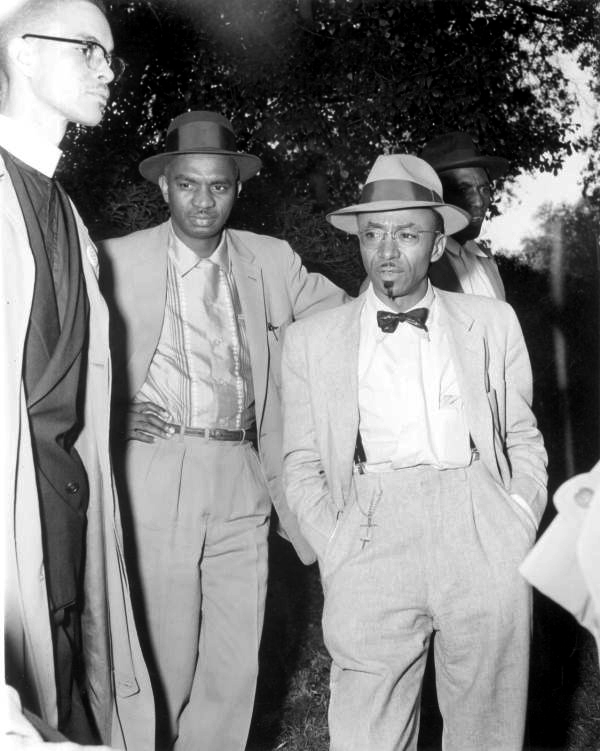

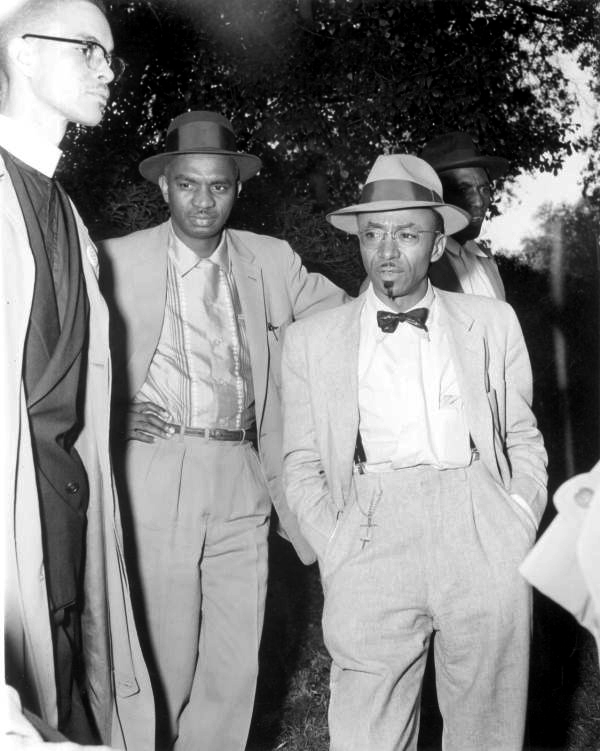

Clergy who protested segregated bus seating in Tallahassee

Reverend C. K. Steele (right) and Edwin Norwood (middle) protested segregated seating on Tallahassee city buses in December 1956, almost seven months after the boycott began.

Reverend C. K. Steele (on left) and Reverend H. McNeal Harris protesting segregated bus seating in Tallahassee

Seth Gaines and his taxi

Seth Gaines drove an independent taxi in the 1940s and 1950s. As a result of demands from civil rights activists during the 1956-57 bus boycott, he became the first African-American to drive buses on a regular route for Tallahassee City Transit.

Sit-Ins Lead to the First Jail‑In of the Civil Rights Movement

Tallahassee witnessed several sit-ins in the early 1960s at prominent businesses that maintained “whites only” lunch counters. The first sit-in in Florida’s capital city took place on February 13, 1960. On February 20, students from Florida A&M University and others from around the country held a sit-in at the Woolworth lunch counter in downtown Tallahassee. When they refused to leave, 11 were arrested and charged with “disturbing the peace by engaging in riotous conduct and assembly to the disturbance of the public tranquility.”

Rather than pay their fines, eight students opted for jail time, effectively launching the first jail-in of the civil rights movement. Among those jailed were Patricia Stephens and her sister Priscilla. In the weeks that followed, additional demonstrations took place at the same Woolworth and also at McCrory’s department store.

While imprisoned, Patricia wrote a letter about her experience and her thoughts on civil rights, which reached leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Jackie Robinson. King wrote back to Stephens: “…you are suffering to make men free.” Almost three years later, King authored his own letter from a Birmingham jail.

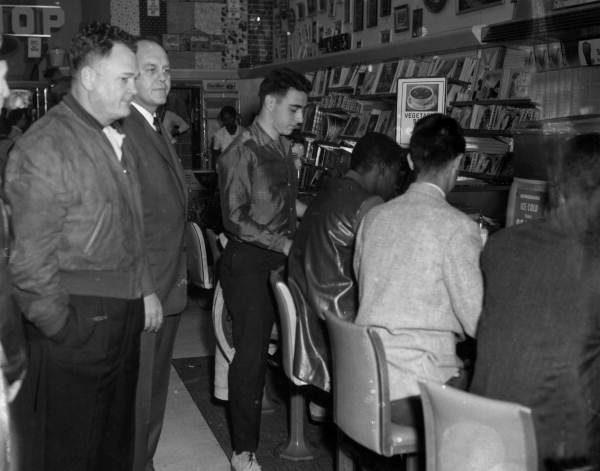

CORE members during sit-in at Woolworth's lunch counter in Tallahassee, 1960

Using tactics learned at a Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) workshop in Miami, the Stephens sisters held their first sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Tallahassee on February 13, 1960.

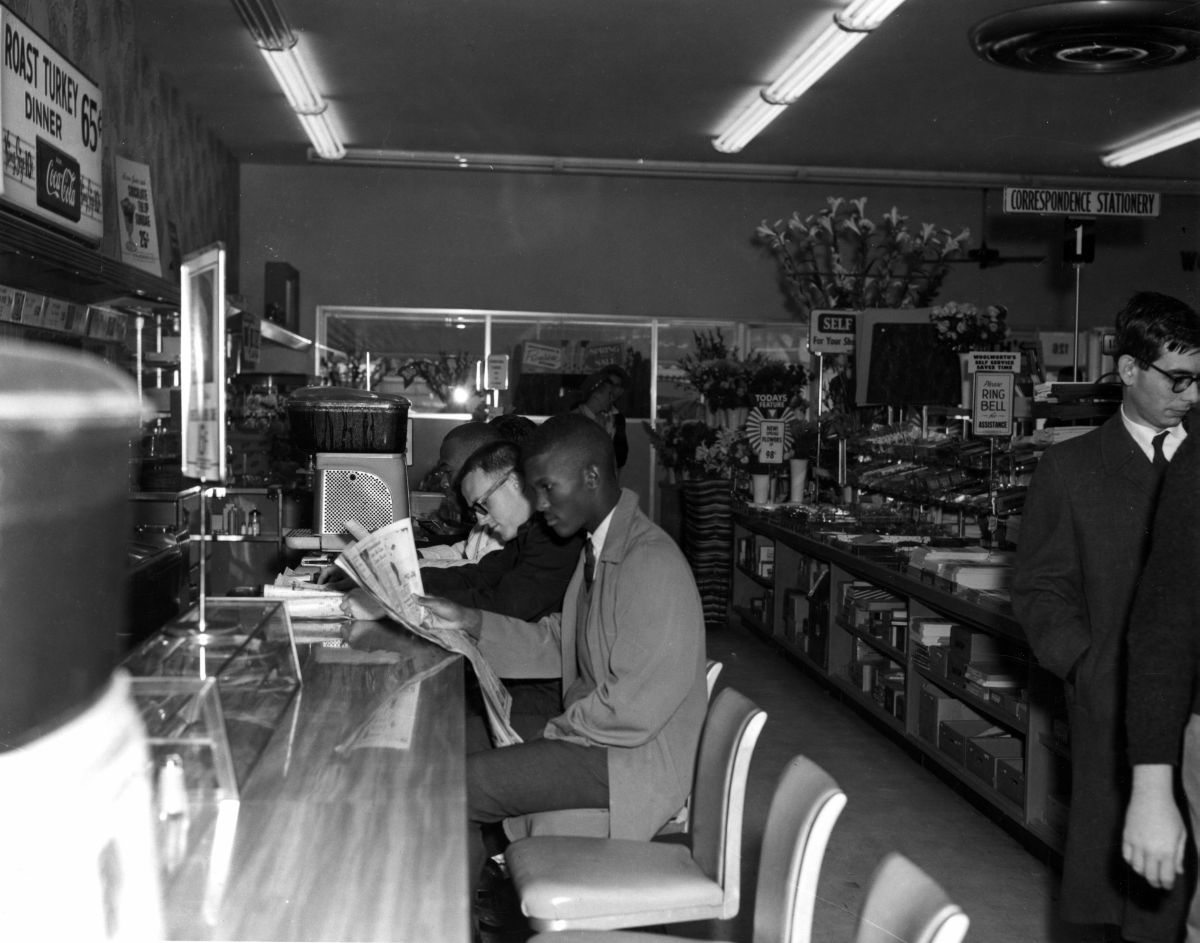

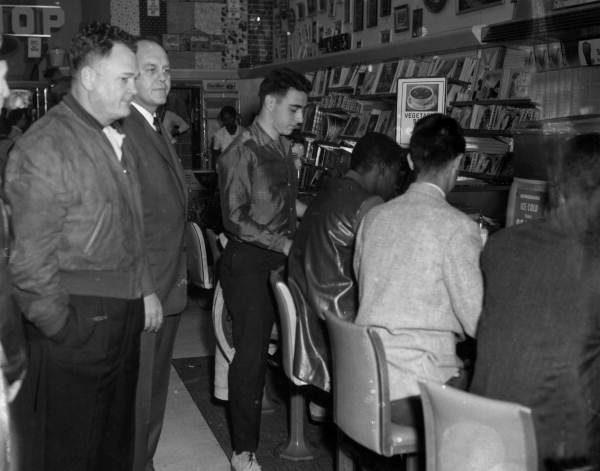

Sit-in at Woolworth's lunch counter in Tallahassee, 1960

Policeman Joe Gregory and City manager Arvah Hopkins are also pictured in this photograph taken March 13, 1960.

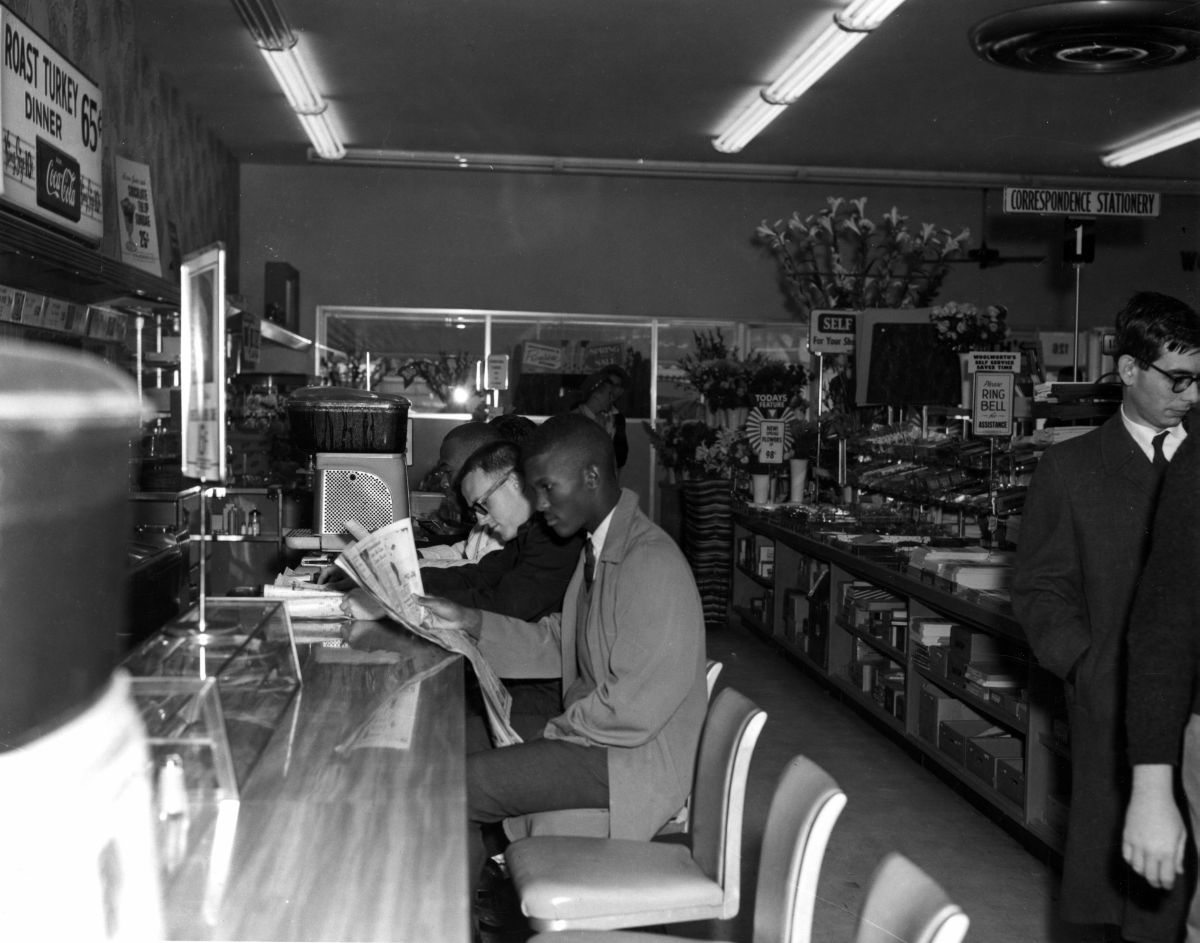

Sit-in at Woolworth's lunch counter, Tallahassee, 1960

Reporter George Thurston stands at the far right in this photograph taken March 13, 1960.

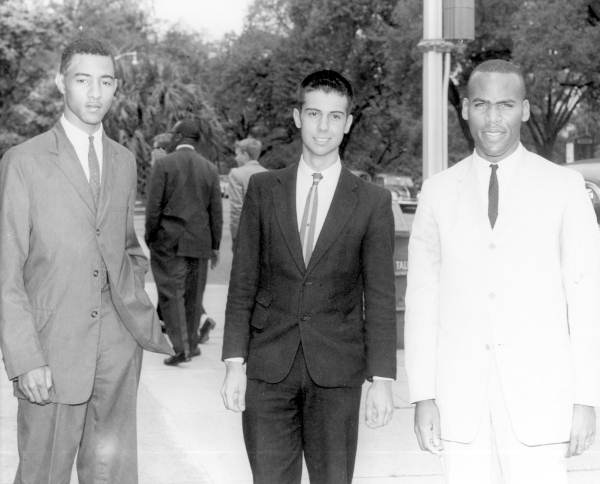

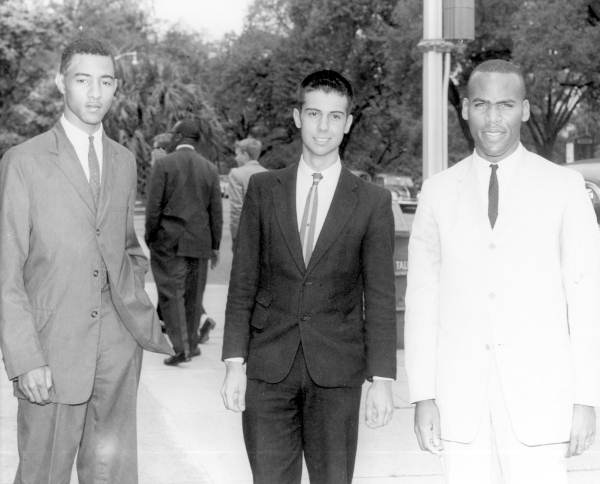

Sit-in defendants in Tallahassee, 1960

Three students tried with unlawful assembly in connection with a March 12 lunch counter sit-in demonstration outside of city hall in Tallahassee during a recess called because of a bomb threat. TFrom left to right: Vecient Moore of Florida A & M University, John J. Poland of Florida State University and Robert F. Kemp of Florida A & M University.

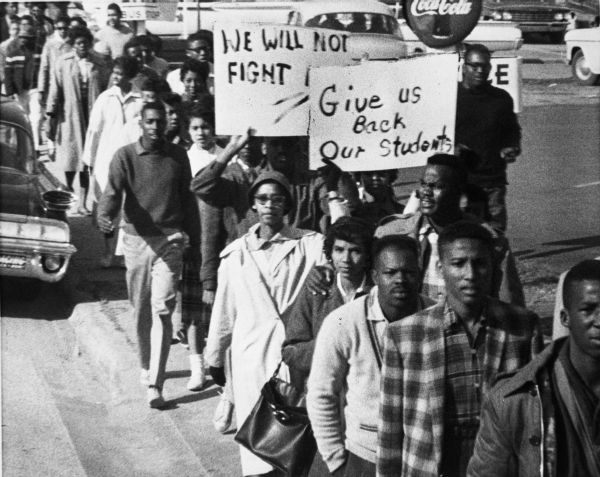

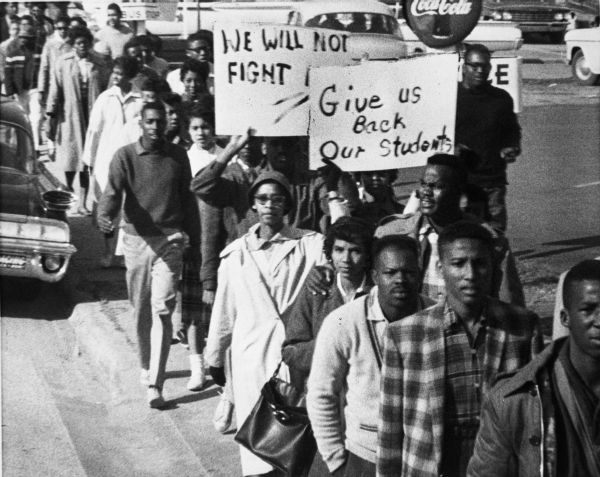

“Give Us Back Our Students”

Florida A&M University students march to protest the arrest of 23 of their classmates who took part in lunch counter demonstrations. The students carry signs reading "Give us back our students” and “We will not fight mobs.”

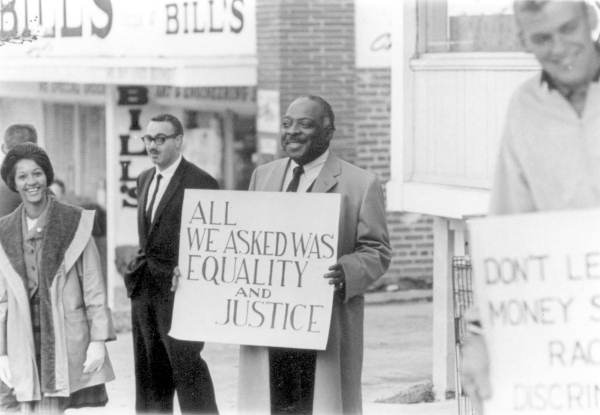

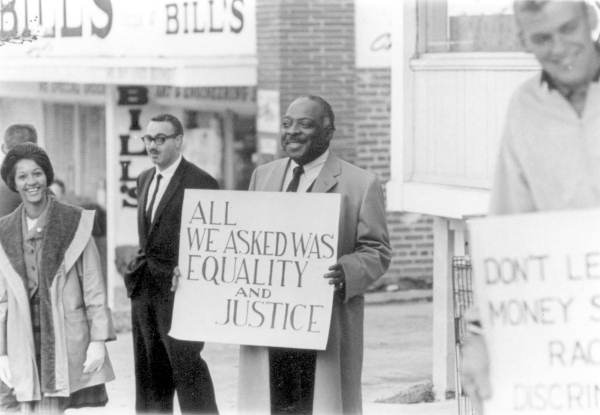

Boycott and picketing of downtown stores in Tallahassee

The boycott and picketing were done because of lack of progress in desegregating the lunch counters at Neisner's, McCrory's, F.W. Woolworth's, Walgreen's and Sears stores.

Boycott and picketing of downtown stores in Tallahassee

Civil rights demonstration in front of a segregated theater in Tallahassee, 1963

Patricia Stephens (dark glasses, black dress) and John Due (shown behind the police officers) participate in the demonstration.

Students filling circuit court room in Tallahassee, 1963

220 African-American students filled a circuit court room to face charges of contempt for demonstrating against segregated movie theaters in Tallahassee.

Musician Count Basie joining civil rights demonstrators in front of the Mecca

The Mecca was a student eatery across from the gate at Florida State University (FSU). Students picketed the Mecca in the fall 1963 as they sought its integration. Count Basie joined the picketers when he was refused service there after playing a concert at FSU in December 1963.

The Tallahassee Ten

In June 1961, Interfaith Freedom Riders challenged segregated interstate buses by traveling from Washington, D.C. to Tallahassee, Florida. After successfully completing the Freedom Ride they planned to fly home but first decided to test whether or not the group would be served in the segregated airport restaurant. After being denied service, 10 Freedom Riders, later known as the Tallahassee Ten, were arrested for unlawful assembly. They were released on bond following their conviction and sentence later that same month, which was followed by about three years of legal appeals. The 10 original riders returned to Tallahassee to serve brief jail terms in August 1964 and were released after serving four days of their 60-day sentences.

Three members of the “Tallahassee Ten” attempting to enter the Savarin Restaurant at the municipal airport, 1961

The members are from left to right: Reverend Robert J. Stone from New York City; Reverend John W. Collier of Newark, New Jersey; and Reverend Wayne Hartmire Jr. from Culver City, California.

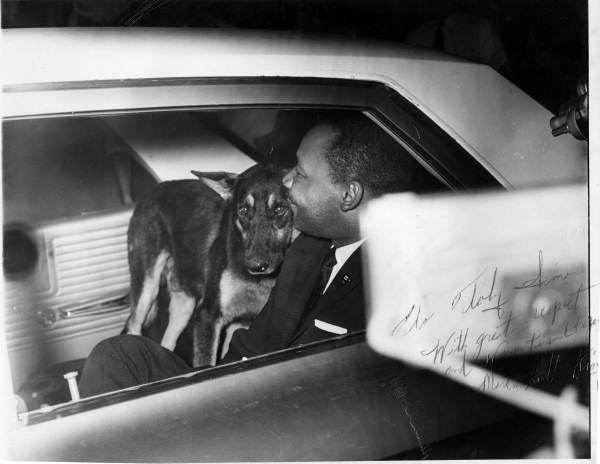

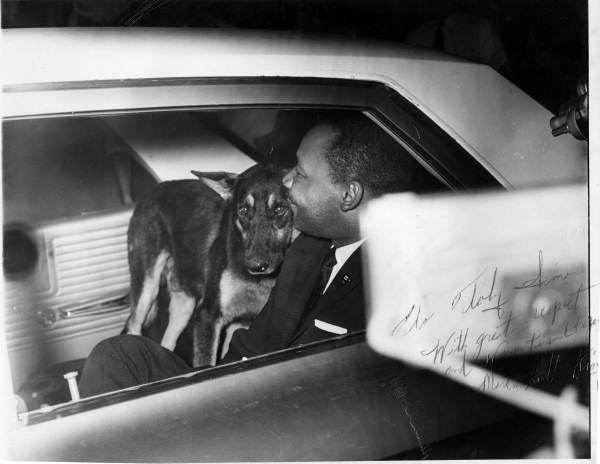

Priscilla Stephens of CORE being arrested at the Tallahassee Regional Airport, 1961

Priscilla Stephens of CORE and Reverend Petty D. McKinney from Nyack, N.Y., in the back of a Tallahassee police car, 1961

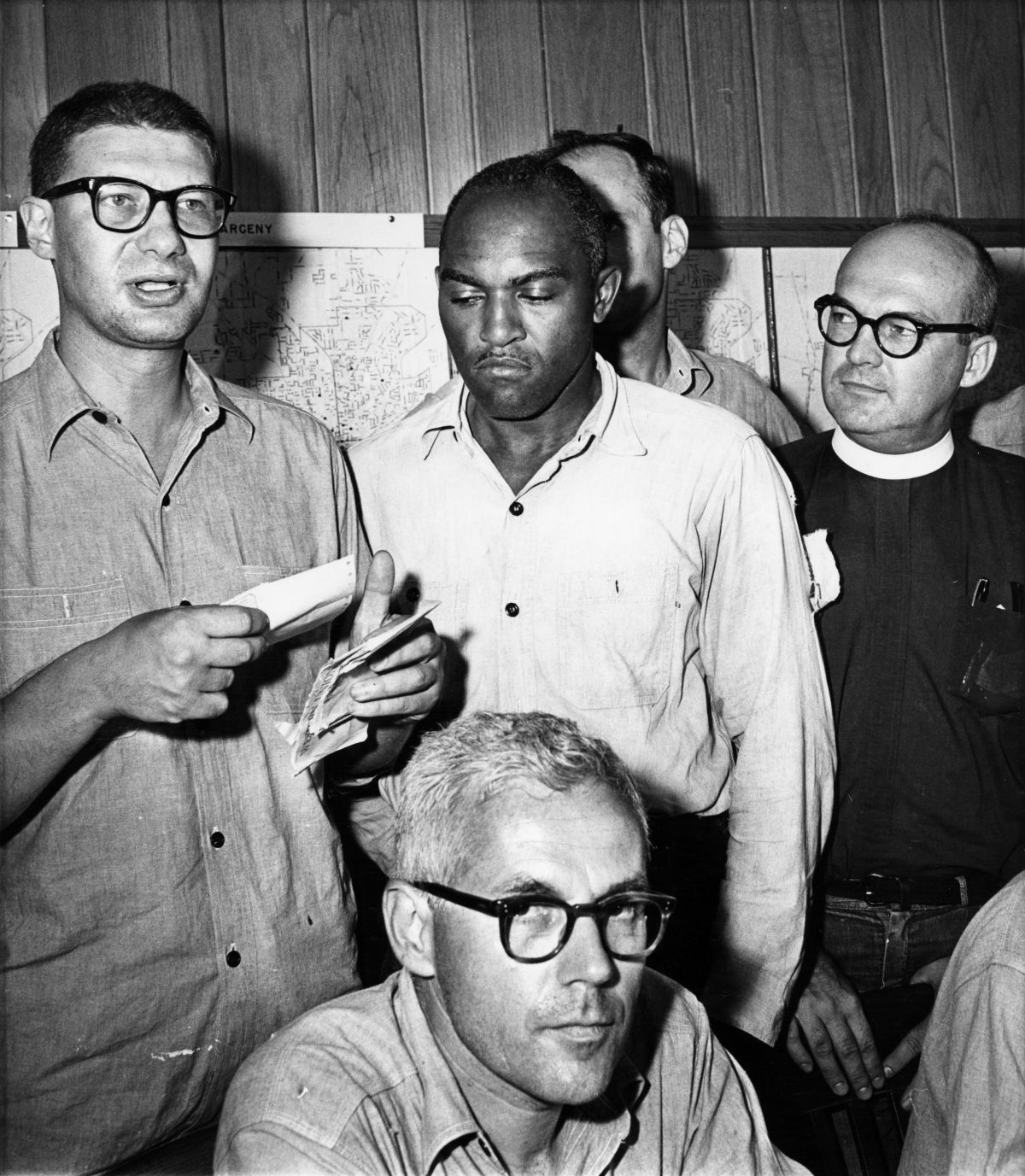

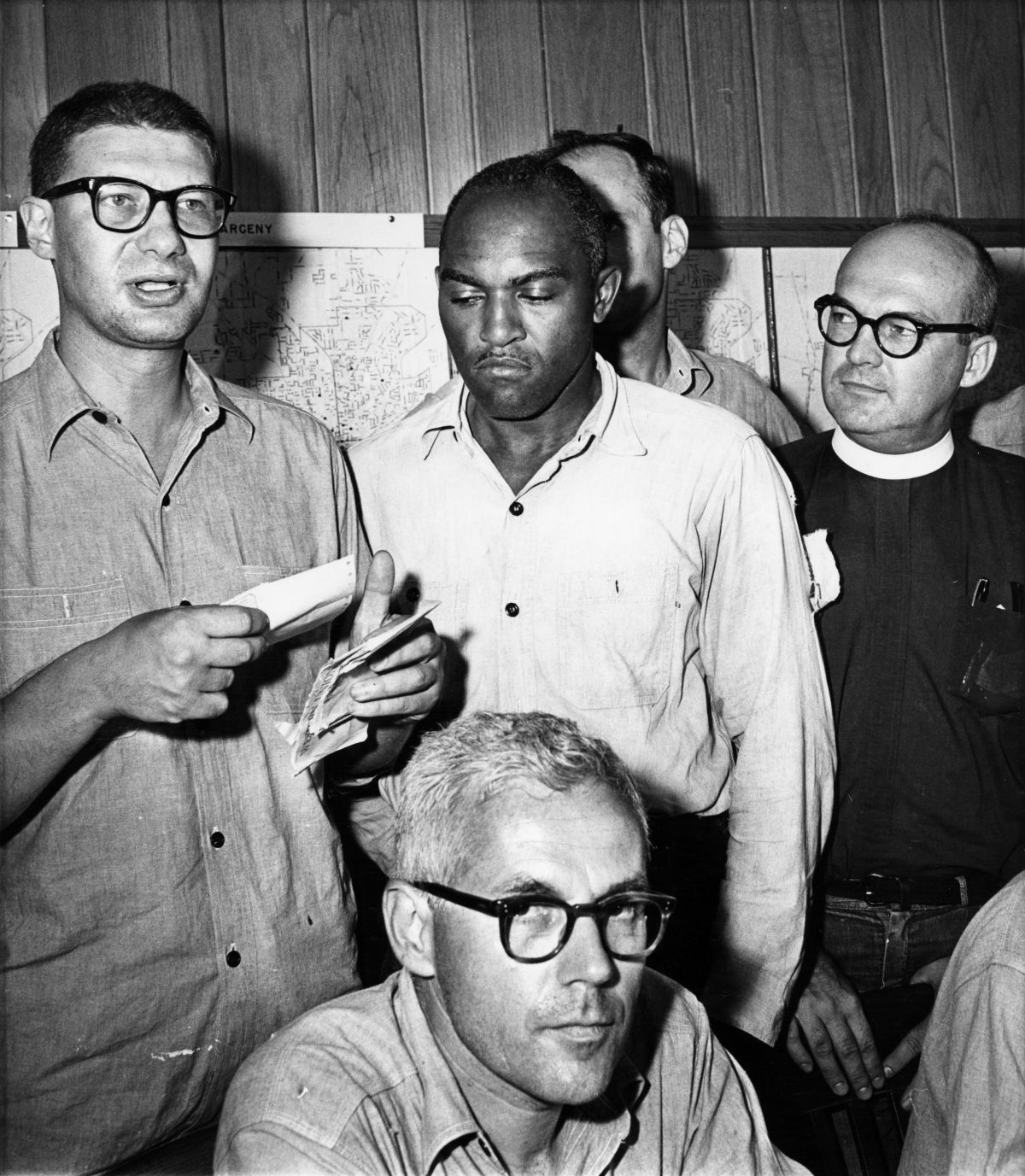

Jailed minister reads support message in Tallahassee, 1964

Rabbi Israel Dresner of Springfield, New Jersey, one of the nine jailed clergymen reads a message of support for their integration activities.

The Tallahassee Ten freed in surprise court action in Tallahassee, 1964

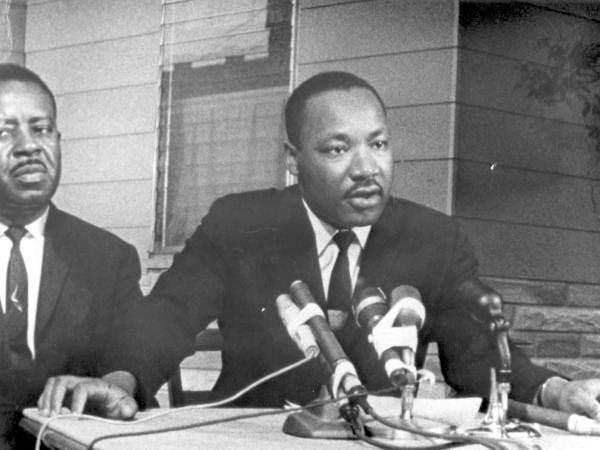

St. Augustine Civil Rights Demonstrations, 1964

The sleepy town of St. Augustine became a major battleground in the civil rights movement during the summer of 1964. Integrationists staged several nonviolent “wade-ins” at segregated hotel pools and beaches in the St. Augustine area. National civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., came to the Ancient City to support the integrationists. For his role in these demonstrations, King was called before a grand jury in St. Augustine to testify on civil rights. The nonviolent tactics of the protestors gradually led to the integration of public recreational facilities in St. Augustine.

Confrontation between integrationists and segregationists at a whites-only beach in St. Augustine, 1964

Segregationists and integrationists at a whites-only beach in St. Augustine, 1964

Segregationists trying to prevent integrationist from swimming at a whites-only beach in St. Augustine, 1964

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) members Dr. R.B. Hayling and Len Murray in St. Augustine

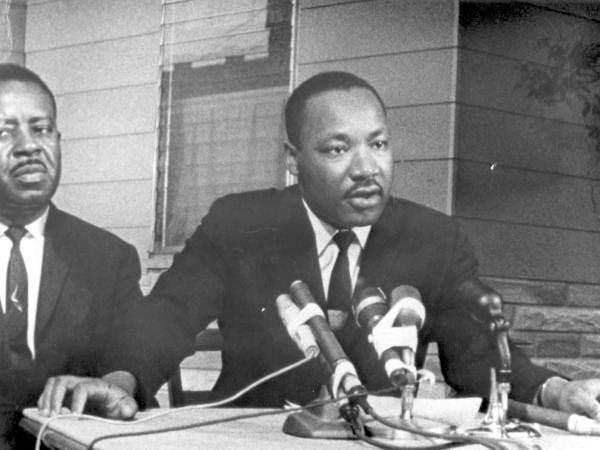

Martin Luther King Jr. being escorted away from the grand jury in St. Augustine

Ralph Abernathy and Martin Luther King Jr. in St. Augustine, 1964

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program