Mary McLeod Bethune

Lesson Plans

Excerpt from Early Draft of Biography

These three pages are excerpted from an early draft of a biography of Mary McLeod Bethune that Daniel Williams wrote but never published.

-20-

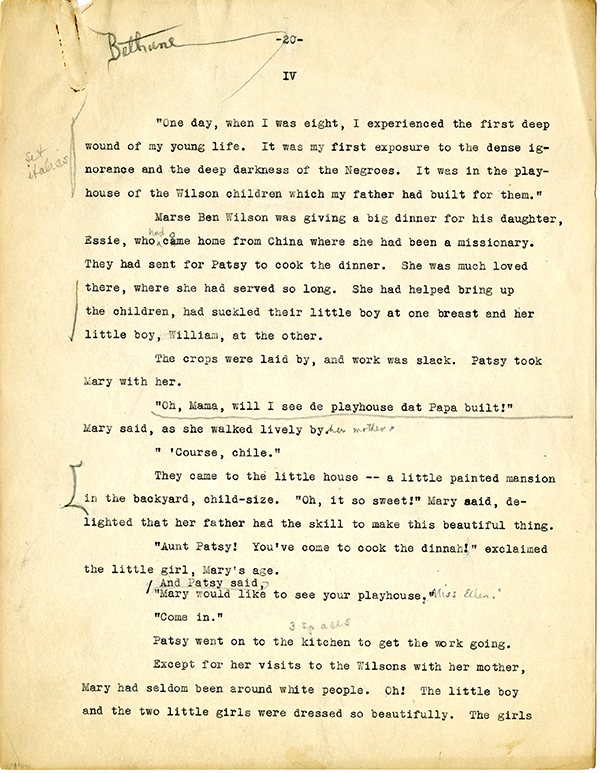

IV

“One day, when I was eight, I experienced the first deep wound of my young life. It was my first exposure to the dense ignorance and the deep darkness of the Negroes. It was in the playhouse of the Wilson children which my father had built for them.”

Marse Ben Wilson was giving a big dinner for his daughter, Essie, who had come home from China where she had been a missionary. They had sent for Patsy to cook the dinner. She was much loved there, where she had served so long. She had helped to bring up the children, had suckled their little boy at one breast and her little boy, William, at the other.

The crops were laid by, and work was slack. Patsy took Mary with her.

“Oh, Mama, will I see de playhouse dat Papa built!” Mary said, as she walked lively by her mother.

“’Course, chile.”

They came to the little house - a little painted mansion in the backyard, child-size. “Oh, it so sweet!” Mary said, delighted that her father had the skill to make this beautiful thing.

“Aunt Patsy! You’ve come to cook the dinnah!” exclaimed the little girl, Mary’s age.

And Patsy said, “Mary would like to see your playhouse, Miss Ellen.”

“Come in.”

Patsy went on to the kitchen to get the work going. Except for her visits to the Wilsons with her mother, Mary had seldom been around white people. Oh! The little boy and the two girls were dressed so beautifully. The girls

IV

“One day, when I was eight, I experienced the first deep wound of my young life. It was my first exposure to the dense ignorance and the deep darkness of the Negroes. It was in the playhouse of the Wilson children which my father had built for them.”

Marse Ben Wilson was giving a big dinner for his daughter, Essie, who had come home from China where she had been a missionary. They had sent for Patsy to cook the dinner. She was much loved there, where she had served so long. She had helped to bring up the children, had suckled their little boy at one breast and her little boy, William, at the other.

The crops were laid by, and work was slack. Patsy took Mary with her.

“Oh, Mama, will I see de playhouse dat Papa built!” Mary said, as she walked lively by her mother.

“’Course, chile.”

They came to the little house - a little painted mansion in the backyard, child-size. “Oh, it so sweet!” Mary said, delighted that her father had the skill to make this beautiful thing.

“Aunt Patsy! You’ve come to cook the dinnah!” exclaimed the little girl, Mary’s age.

And Patsy said, “Mary would like to see your playhouse, Miss Ellen.”

“Come in.”

Patsy went on to the kitchen to get the work going. Except for her visits to the Wilsons with her mother, Mary had seldom been around white people. Oh! The little boy and the two girls were dressed so beautifully. The girls

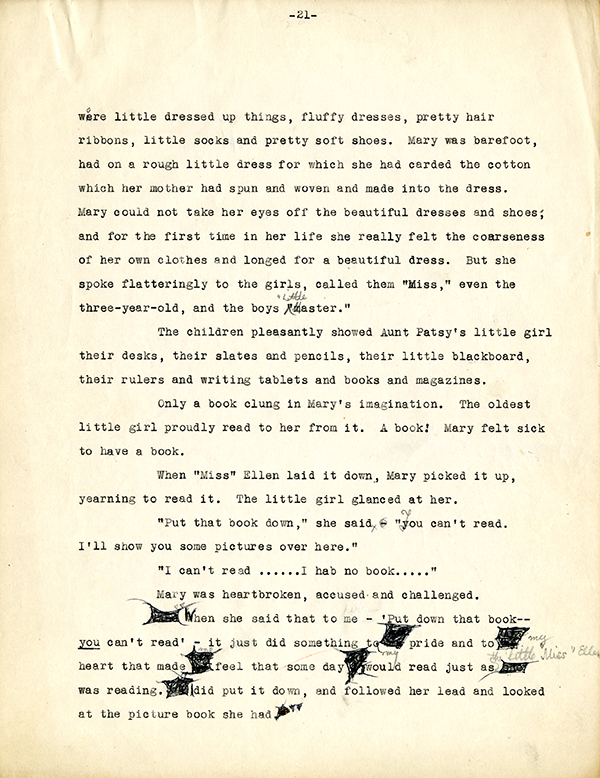

-21-

were little dressed up things, fluffy dresses, pretty hair ribbons, little socks and pretty soft shoes. Mary was barefoot, had on a rough little dress for which she had carded the cotton which her mother had spun and woven and made into the dress. Mary could not take her eyes off the beautiful dresses and shoes; and for the first time in her life she really felt the coarseness of her own clothes and longed for a beautiful dress. But she spoke flatteringly to the girls, called them “Miss,” even the three-year-old, and the boys “Little Master.”

The children pleasantly showed Aunt Patsy’s little girl their desks, their slates and pencils, their little blackboard, their rulers and writing tablets and books and magazines.

Only a book clung in Mary’s imagination. The oldest little girl proudly read to her from it. A book! Mary felt sick to have a book.

When “Miss” Ellen laid it down, Mary picked it up, yearning to read it. The little girl glanced at her.

“Put that book down,” she said. “You can’t read. I’ll show you some pictures over here.”

“I can’t read… I hab no book…”

Mary was heartbroken, accused and challenged.

“When she said that to me - ‘Put down that book - you can’t read” - it just did something to my pride and to my heart that made me feel that some day I would read just as the little Miss Ellen was reading. I did put it down, and followed her lead and looked at the picture book she had.”

were little dressed up things, fluffy dresses, pretty hair ribbons, little socks and pretty soft shoes. Mary was barefoot, had on a rough little dress for which she had carded the cotton which her mother had spun and woven and made into the dress. Mary could not take her eyes off the beautiful dresses and shoes; and for the first time in her life she really felt the coarseness of her own clothes and longed for a beautiful dress. But she spoke flatteringly to the girls, called them “Miss,” even the three-year-old, and the boys “Little Master.”

The children pleasantly showed Aunt Patsy’s little girl their desks, their slates and pencils, their little blackboard, their rulers and writing tablets and books and magazines.

Only a book clung in Mary’s imagination. The oldest little girl proudly read to her from it. A book! Mary felt sick to have a book.

When “Miss” Ellen laid it down, Mary picked it up, yearning to read it. The little girl glanced at her.

“Put that book down,” she said. “You can’t read. I’ll show you some pictures over here.”

“I can’t read… I hab no book…”

Mary was heartbroken, accused and challenged.

“When she said that to me - ‘Put down that book - you can’t read” - it just did something to my pride and to my heart that made me feel that some day I would read just as the little Miss Ellen was reading. I did put it down, and followed her lead and looked at the picture book she had.”

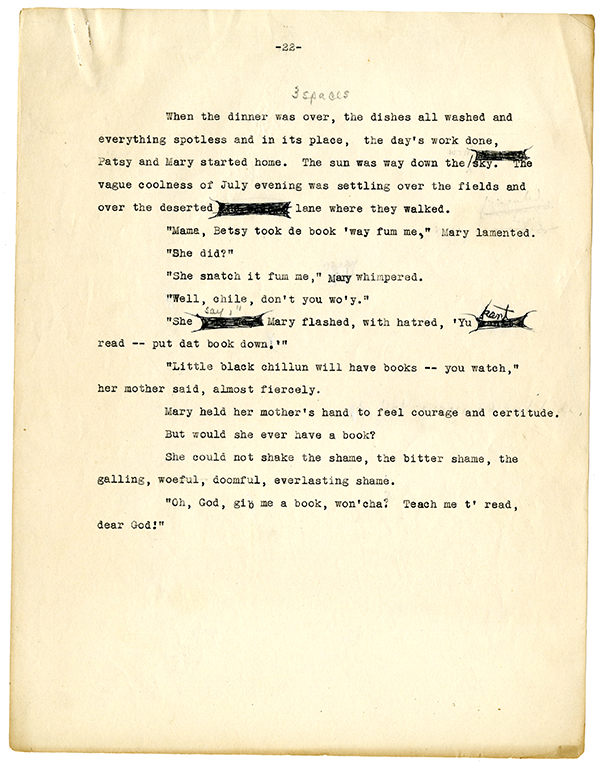

-22-

When dinner was over, the dishes all washed and everything spotless and in its place, the day’s work done, Patsy and Mary started home. The sun was way down the sky. The vague coolness of July evening was settling over the fields and over the deserted land where they walked.

“Mama, Betsy took de book ‘way fum me,” Mary lamented.

“She did?”

“She snatch it fum me,” Mary whimpered.

“Well, chile, don’t you wo’y.”

“She say,” Mary flashed, with hatred, ‘Yu can’t read - put dat book down.’”

“Little black chillun will have books - you watch,” her mother said, almost fiercely.

Mary held her mother’s hand to feel courage and certitude.

But would she ever have a book?

She could not shake the shame, the bitter shame, the galling, woeful, doomful, everlasting shame.

“Oh, God, gib me a book, won’cha? Teach me t’ read, de God!”

When dinner was over, the dishes all washed and everything spotless and in its place, the day’s work done, Patsy and Mary started home. The sun was way down the sky. The vague coolness of July evening was settling over the fields and over the deserted land where they walked.

“Mama, Betsy took de book ‘way fum me,” Mary lamented.

“She did?”

“She snatch it fum me,” Mary whimpered.

“Well, chile, don’t you wo’y.”

“She say,” Mary flashed, with hatred, ‘Yu can’t read - put dat book down.’”

“Little black chillun will have books - you watch,” her mother said, almost fiercely.

Mary held her mother’s hand to feel courage and certitude.

But would she ever have a book?

She could not shake the shame, the bitter shame, the galling, woeful, doomful, everlasting shame.

“Oh, God, gib me a book, won’cha? Teach me t’ read, de God!”

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program