Mary McLeod Bethune

Lesson Plans

Interview with Mary McLeod Bethune, ca. 1940

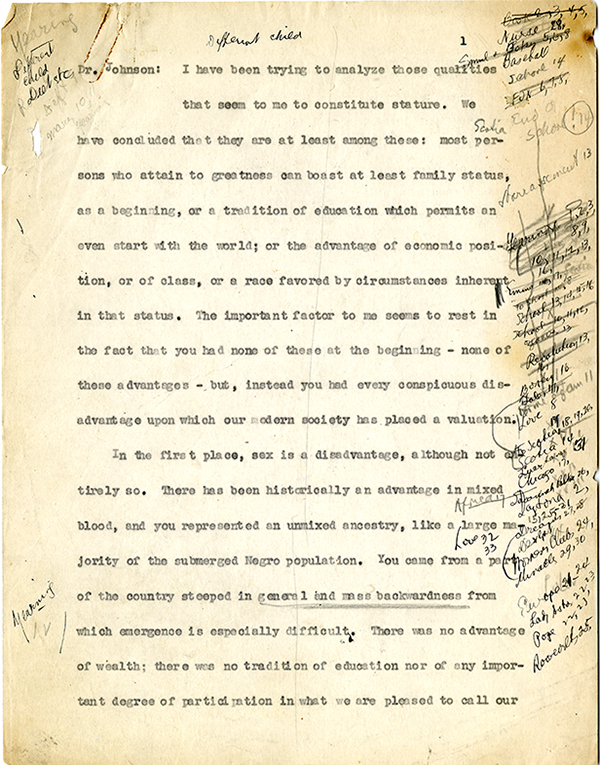

This document is a transcript of an interview apparently conducted in about 1939 or 1940 by Dr. Charles Spurgeon Johnson, an authority on race relations who chaired the Sociology Department and was later the first black president at historically black Fisk University.

Page 1

Dr. Johnson: I have been trying to analyze those qualities that seem to me to constitute stature.

We have concluded that they are at least among these: most persons who attain to greatness can boast at least family status, as a beginning, or a tradition of education which permits an even start with the world: or the advantage of economic position, or of class, or a race favored by circumstances inherent in that status.

The important factor to me seems to rest in the fact that you had none of these at the beginning – none of these advantages – but, instead you had every conspicuous disadvantage upon which our modern society has placed a valuation.

In the first place, sex is a disadvantage, although not entirely so. There has been historically an advantage in mixed blood, and you represent an unmixed ancestry, like a large majority of the submerged Negro population. You came from a part of the country steeped in general and mass backwardness from which emergence is especially difficult. There was no advantage of wealth; there was no tradition of education nor of any important degree of participation in what we are pleased to call our American civilization.

We have concluded that they are at least among these: most persons who attain to greatness can boast at least family status, as a beginning, or a tradition of education which permits an even start with the world: or the advantage of economic position, or of class, or a race favored by circumstances inherent in that status.

The important factor to me seems to rest in the fact that you had none of these at the beginning – none of these advantages – but, instead you had every conspicuous disadvantage upon which our modern society has placed a valuation.

In the first place, sex is a disadvantage, although not entirely so. There has been historically an advantage in mixed blood, and you represent an unmixed ancestry, like a large majority of the submerged Negro population. You came from a part of the country steeped in general and mass backwardness from which emergence is especially difficult. There was no advantage of wealth; there was no tradition of education nor of any important degree of participation in what we are pleased to call our American civilization.

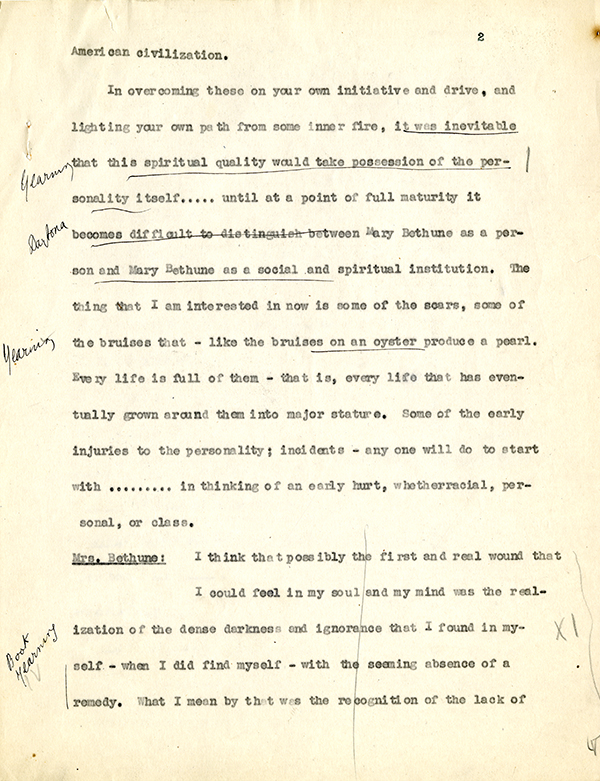

Page 2

In overcoming these on your own initiative and drive, and lighting your own path from some inner fire, it was inevitable that this spiritual quality would take possession of the personality itself….. until at a point of full maturity it becomes difficult to distinguish between Mary Bethune as a person and Mary Bethune as a social and spiritual institution.

The thing that I am interested in now is some of the scars, some of the bruises that – like the bruises on an oyster produce a pearl.

Every life is full of them – that is, every life that has eventually grown around them into major stature. Some of the early injuries to the personality: incidents – any one will do to start with………in thinking of an early hurt, whether racial, personal, or class.

Mrs. Bethune: I think that possibly the first and real wound that I could feel in my soul and my mind was the realization of the dense darkness and ignorance that I found in myself – when I did find myself – with the seeming absence of a remedy. What I mean by that was the recognition of the lack of opportunity.

The thing that I am interested in now is some of the scars, some of the bruises that – like the bruises on an oyster produce a pearl.

Every life is full of them – that is, every life that has eventually grown around them into major stature. Some of the early injuries to the personality: incidents – any one will do to start with………in thinking of an early hurt, whether racial, personal, or class.

Mrs. Bethune: I think that possibly the first and real wound that I could feel in my soul and my mind was the realization of the dense darkness and ignorance that I found in myself – when I did find myself – with the seeming absence of a remedy. What I mean by that was the recognition of the lack of opportunity.

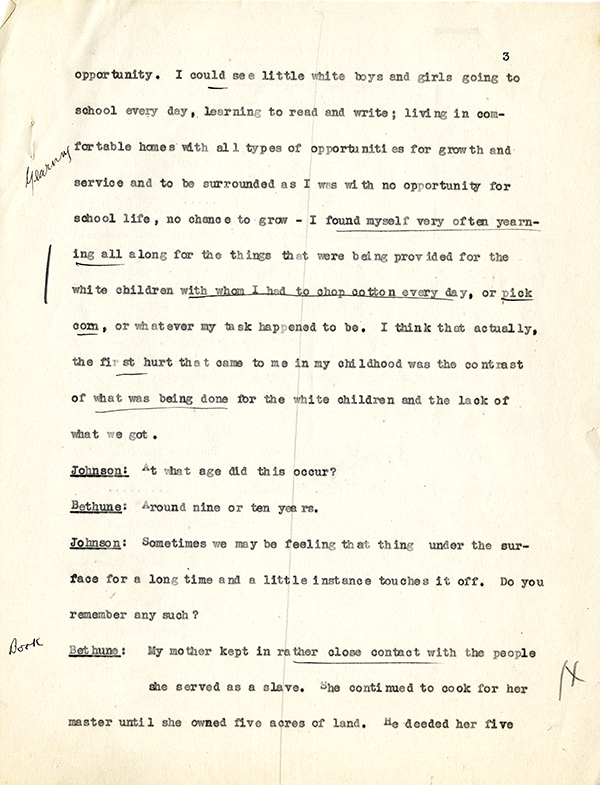

Page 3

I could see little white boys and girls going to school every day, learning to read and write; living in comfortable homes with all types of opportunities for growth and service and to be surrounded as I was with no opportunity for school life, no chance to grow – I found myself very often yearning all along for the things that were being provided for the white children with whom I had to chop cotton every day, or pick corn, or whatever my task happened to be.

I think that actually, the first hurt that came to me in my childhood was the contrast of what was being done for the white children and the lack of what we got.

Johnson: At what age did this occur?

Bethune: Around nine or ten years.

Johnson: Sometimes we may be feeling that thing under the surface for a long time and a little instance touches it off. Do you remember any such?

Bethune: My mother kept in rather close contact with the people she served as a slave. She continued to cook for her master until she owned five acres of land. He deeded her five acres. The cabin, my father and brothers built. It was the cabin in which I was born.

I think that actually, the first hurt that came to me in my childhood was the contrast of what was being done for the white children and the lack of what we got.

Johnson: At what age did this occur?

Bethune: Around nine or ten years.

Johnson: Sometimes we may be feeling that thing under the surface for a long time and a little instance touches it off. Do you remember any such?

Bethune: My mother kept in rather close contact with the people she served as a slave. She continued to cook for her master until she owned five acres of land. He deeded her five acres. The cabin, my father and brothers built. It was the cabin in which I was born.

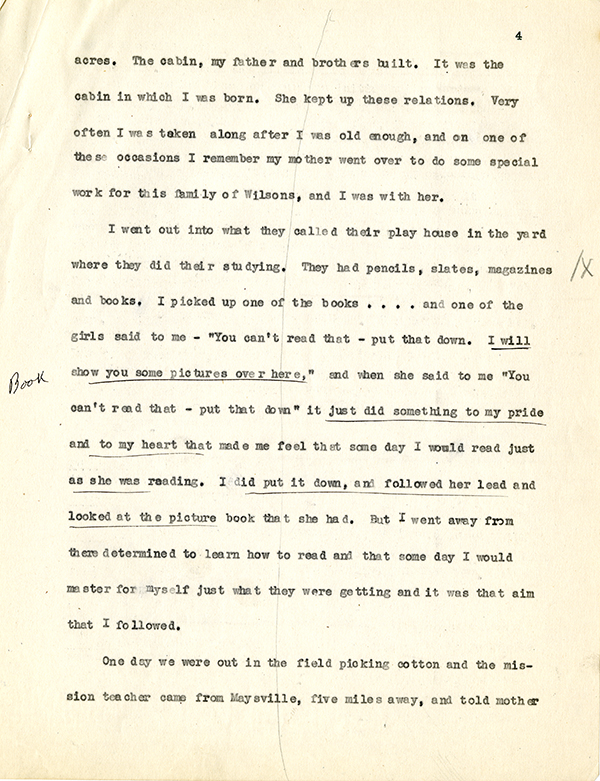

Page 4

She kept up these relations. Very often I was taken along after I was old enough, and on one of these occasions I remember my mother went over to do some special work for this family of Wilsons, and I was with her. I went out into what they called their play house in the yard where they did their studying. They had pencils, slates, magazines and books.

I picked up one of the books . . . . and one of the girls said to me – “You can’t read that – put that down. I will show you some pictures over here,” and when she said to me “You can’t read that– put that down” it just did something to my pride and to my heart that made me feel that some day I would read just as she was reading.

I did put it down, and followed her lead and looked at the picture book that she had. But I went away from there determined to learn how to read and that some day I would master for myself just what they were getting and it was that aim that I followed.

One day we were out in the field picking cotton and the mission teacher came from Maysville, five miles away, and told mother and father that the Presbyterian church had established a mission where the Negro children could go and that the children would be allowed to go. I was among the first of the young ones to enroll, and …. so it seemed to me.

I picked up one of the books . . . . and one of the girls said to me – “You can’t read that – put that down. I will show you some pictures over here,” and when she said to me “You can’t read that– put that down” it just did something to my pride and to my heart that made me feel that some day I would read just as she was reading.

I did put it down, and followed her lead and looked at the picture book that she had. But I went away from there determined to learn how to read and that some day I would master for myself just what they were getting and it was that aim that I followed.

One day we were out in the field picking cotton and the mission teacher came from Maysville, five miles away, and told mother and father that the Presbyterian church had established a mission where the Negro children could go and that the children would be allowed to go. I was among the first of the young ones to enroll, and …. so it seemed to me.

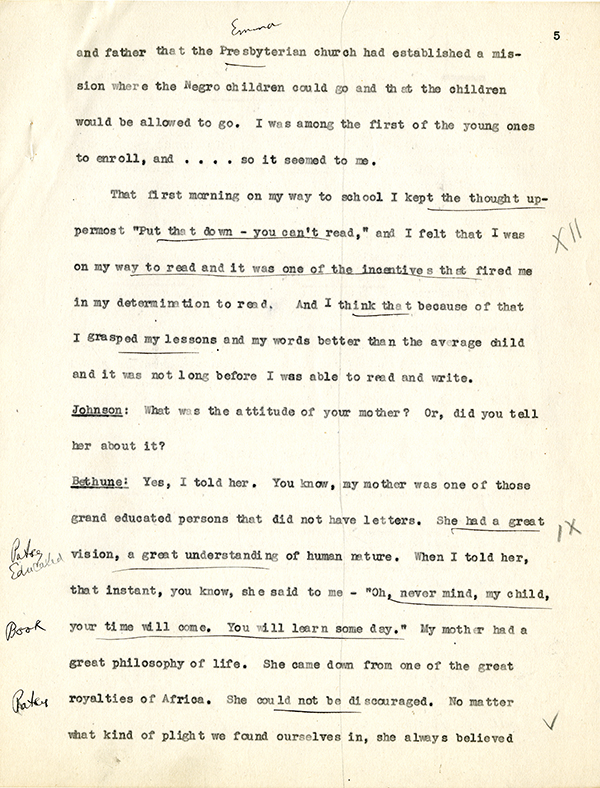

Page 5

That first morning on my way to school I kept the thought uppermost “Put that down – you can’t read,” and I felt that I was on my way to read and it was one of the incentives that fired me in my determination to read. And I think that because of that I grasped my lessons and my words better than the average child and it was not long before I was able to read and write.

Johnson: What was the attitude of your mother? Or, did you tell her about it?

Bethune: Yes, I told her. You know, my mother was one of those grand educated persons that did not have letters. She had a great vision, a great understanding of human nature. When I told her, that instant, you know, she said to me – “Oh, never mind, my child, your time will come. You will learn some day.”

My mother had a great philosophy of life. She came down from one of the great royalties of Africa. She could not be discouraged. No matter what kind of plight we found ourselves in, she always believed there was, through prayer and work, a way out. And it was one of the greatest things she stimulated life with….that determination that there was a way out if we put forth effort ourselves.

Johnson: What was the attitude of your mother? Or, did you tell her about it?

Bethune: Yes, I told her. You know, my mother was one of those grand educated persons that did not have letters. She had a great vision, a great understanding of human nature. When I told her, that instant, you know, she said to me – “Oh, never mind, my child, your time will come. You will learn some day.”

My mother had a great philosophy of life. She came down from one of the great royalties of Africa. She could not be discouraged. No matter what kind of plight we found ourselves in, she always believed there was, through prayer and work, a way out. And it was one of the greatest things she stimulated life with….that determination that there was a way out if we put forth effort ourselves.

Page 6

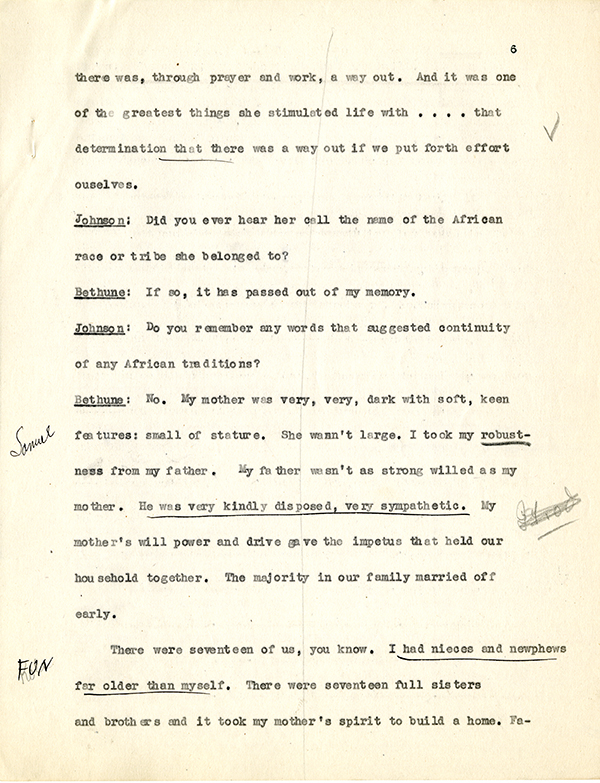

Johnson: Did you ever hear her call the name of the African race of tribe she belonged to?

Bethune: If so, it has passed out of my memory.

Johnson: Do you remember any words that suggested continuity of any African tradition?

Bethune: No. My mother was very, very, dark with soft, keen features: small of stature. She wasn’t large. I took my robustness from my father. My father wasn’t as strong willed as my mother. He was very kindly disposed, very sympathetic. My mother’s will power and drive gave the impetus that held our household together. The majority in our family married off early.

There were seventeen of us, you know. I had nieces and nephews far older than myself. There were seventeen full sisters and brothers and it took my mother’s spirit to build a home.

Father and my brothers got the logs that built the cabin, the cabin where I was born – I was born in our own home cabin, and on our own soil.

Bethune: If so, it has passed out of my memory.

Johnson: Do you remember any words that suggested continuity of any African tradition?

Bethune: No. My mother was very, very, dark with soft, keen features: small of stature. She wasn’t large. I took my robustness from my father. My father wasn’t as strong willed as my mother. He was very kindly disposed, very sympathetic. My mother’s will power and drive gave the impetus that held our household together. The majority in our family married off early.

There were seventeen of us, you know. I had nieces and nephews far older than myself. There were seventeen full sisters and brothers and it took my mother’s spirit to build a home.

Father and my brothers got the logs that built the cabin, the cabin where I was born – I was born in our own home cabin, and on our own soil.

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program