Florida and the Apollo Program

We Choose to Go to the Moon

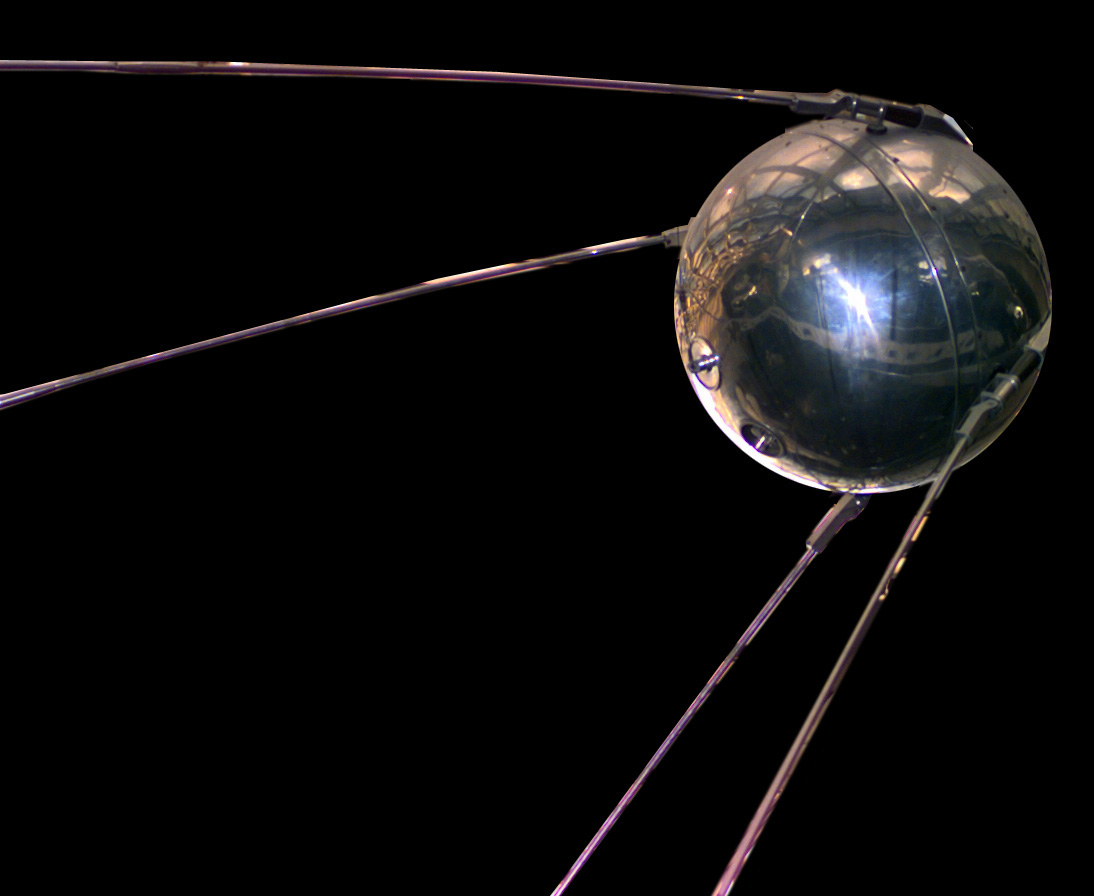

By the time NASA announced the start of the Apollo program in 1960, the Space Race was already well underway. Americans had listened to their radios with awe and anxiety in October 1957 as the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1,the first to orbit the Earth, beeped faintly. Beeping was actually all Sputnik could do, but that was enough. As far as the American public was concerned, the Soviet Union had scored a significant victory that threatened the United States’ supremacy in science, technology and the Cold War itself. It didn’t help that the Vanguard rocket intended to carry the American answer to Sputnik into space exploded on its launch pad a month later. Even if the rocket had succeeded, the would-be American satellite weighed a paltry four pounds compared with the 180-pound satellite the Soviets had launched. Something had to be done.

In the search for scapegoats after Sputnik, the American education system received a hefty share of the blame. Many people assumed that the Soviet Union could only have achieved a technological feat like Sputnik by having a superior program of math and science education that turned out more and better scientists and technicians than the United States. Journalists, politicians and scientists put American high schools and colleges under a microscope, blasting what they saw as a lack of emphasis on serious academic work, coupled with inadequate funding, especially for postgraduate learning.

Florida’s Nuclear Commission established a special committee in 1959 to investigate math and science instruction in the public schools, and came away with many of the same conclusions. “Competent authorities advise us,” they wrote, “that the science program for our junior high school grades is poorly organized, repetitive and unchallenging.” The committee named off a list of recommendations to get the state back on track for competency in the Space Race. “The truth of the matter is that we are now concerned with the possible survival of the free world,” the committee wrote. “Our educational system is very much a part of our national defense system and must be given the priorities demanded by our national defense.”

Educators tended to agree with the part about inadequate funding, but they also stressed that the American public didn’t place a high enough value on intellectual curiosity and talent. “Our measure of success is too frequently not knowledge but material wealth,” Florida’s superintendent of public education Thomas Bailey said in 1959. “The student who excels in scholarship is often shunned by his fellow students and unrecognized by his community.” Bailey and other education experts also warned that crash programs aiming to pressure-cook students into the next generation of scientists would not work. “All knowledge is interdependent,” wrote one official from the Florida Education Association. “Let’s not be part-smart.”

Educating the Space Age Generation

Eager to attack these problems, everyone from parent-teacher groups to Congress began proposing programs to beef up science and math instruction in American high schools and stimulate student interest in those subjects. In 1958, President Dwight Eisenhower signed the National Defense Education Act, which funded loans and graduate fellowships for students aiming to study science, math and foreign languages. High schools began adopting new diploma programs that emphasized these subjects. School boards spent millions building new classrooms and buying updated books to bring their programs up to date. Science and rocketry clubs flourished with added encouragement from teachers and school administrators.

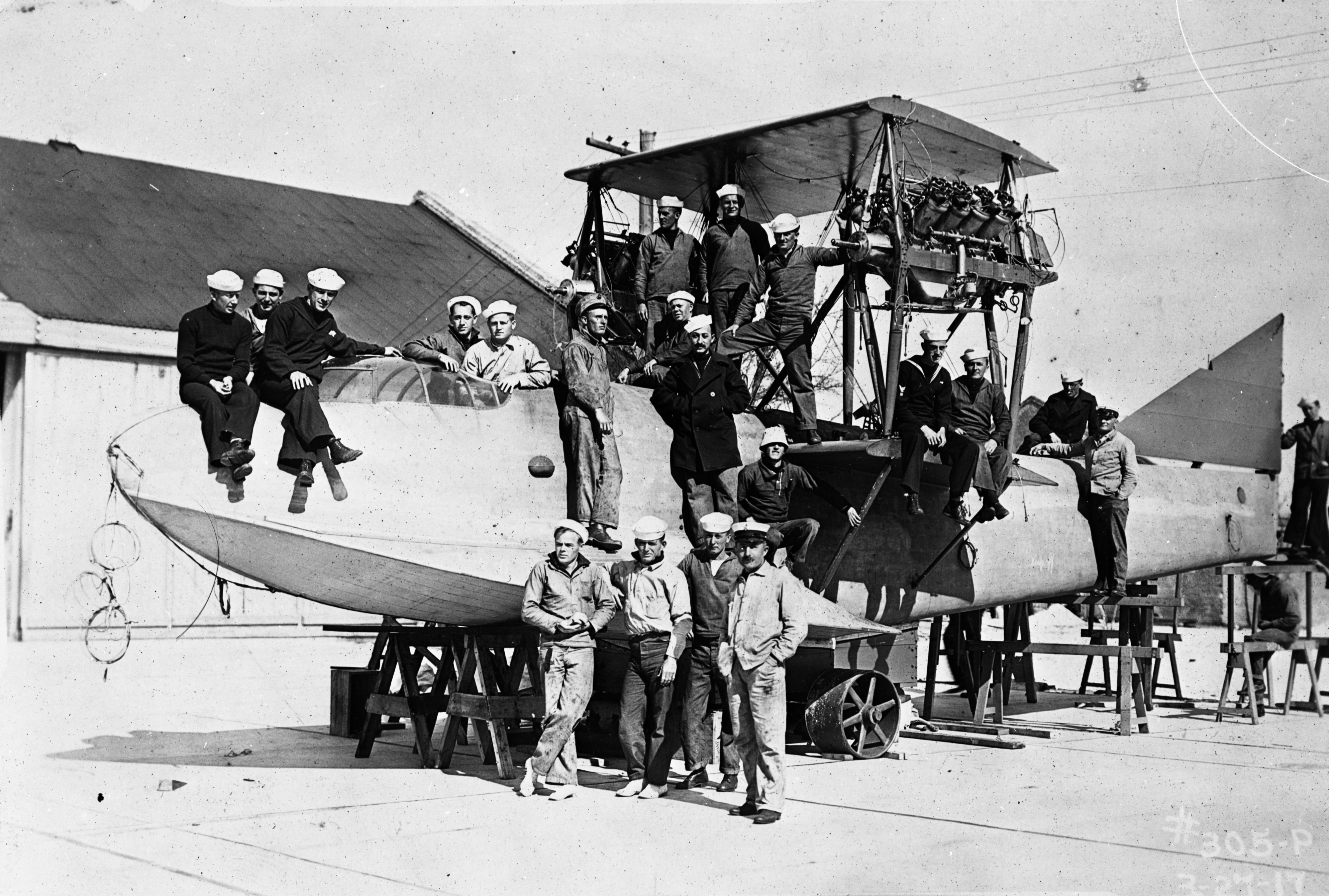

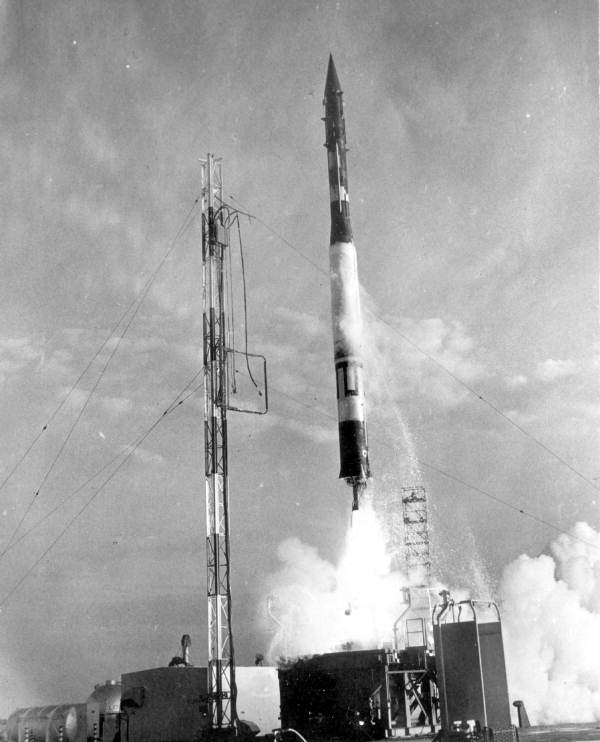

Educating the next generation of scientists and engineers was one way to respond, but in Washington the pressure was on to do something more, and quickly. The Eisenhower administration publicly downplayed the significance of the Sputnik launch but behind the scenes looked for ways to expedite the nation’s space program. On January 31, 1958, a Juno rocket lifted off from Cape Canaveral and successfully carried the satellite Explorer 1 into space. Later that year, Senate majority leader Lyndon B. Johnson shepherded the Aeronautics and Space Act through Congress, paving the way for Eisenhower to officially establish NASA on October 1. Up to this point, the military had controlled the development of American rocketry. NASA, however, would be a civilian agency, and it inherited all nonmilitary space projects and the facilities associated with them.

NASA unveiled a roadmap for its work in early 1960, a Ten Year Plan of Space Exploration. It called for spending about $12.5 billion (more than $100 billion in 2019 dollars) to develop space vehicles and launch missions into orbit and beyond. The planners estimated they would put their first astronaut into space in 1961, and send their first lunar exploration team sometime after 1970. Key to these achievements would be the development of new rocket boosters that would surpass everything the Soviets had been able to produce so far in the Space Race.

Congress approved the plan but wanted NASA to move faster. The Soviets had already struck another psychological blow by successfully sending a spacecraft past the Moon and taking the first photographs of its dark side in 1959. With the satellite firsts quickly disappearing out of reach, the U.S. focused its sights on manned space flight. The Mercury program, established in 1958 by NASA engineers at Langley Laboratory in Virginia, aimed to put a human into orbit within two years. They succeeded, but not on time and not before the Soviets had successfully launched cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into orbit aboard Vostok 1 on April 12, 1961. Losing that round of the Space Race, combined with the embarrassment stemming from the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion days later, helped nudge the new president, John F. Kennedy, toward supporting an expedited timeline for landing humans on the Moon.

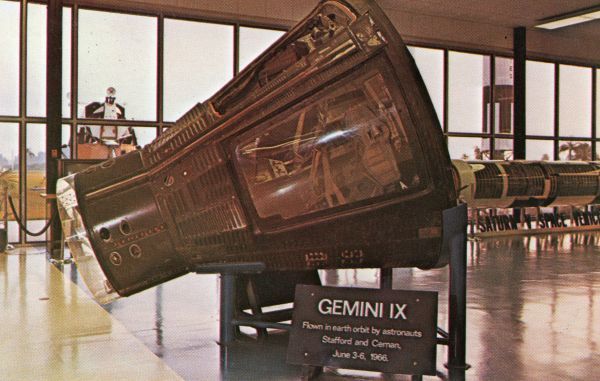

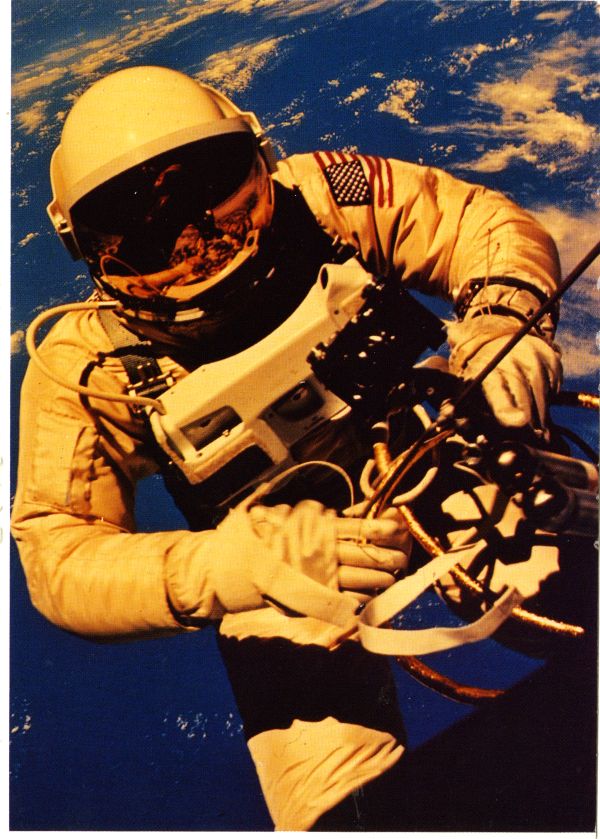

Project Apollo, which aimed to send three astronauts either into a sustained orbit around the Earth or on a trip around the moon, had already been announced back in July 1960. The Mercury and Gemini programs were stepping stones toward those objectives. President Kennedy originally hesitated on committing to the full Apollo program because of its expense, but by late spring 1961 it was becoming an increasingly attractive option for recouping some of the prestige many observers felt the United States was losing to the Soviets.

On May 25, 1961, Kennedy went before Congress and called for the U.S. to land on the Moon before the end of the decade. “Now is the time to take longer strides,” he said, “Time for a great new American enterprise—time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth.” He reiterated these ideas in a speech at Rice University the following year. “We choose to go to the Moon,” Kennedy exclaimed to enthusiastic applause. “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

Kennedy’s bold vision for America’s future in space drew little criticism in the ensuing months. The public and Congress seemed to feel the same sense of urgency that the president felt, and the funding and goodwill NASA needed to achieve its mission began to flow. Floridians, like most Americans, were dazzled by the project’s magnitude and cost, but were especially cognizant of the project’s likely benefits. In addition to reclaiming international prestige in the Space Race, Apollo would bring a major infusion of growth and capital to the Sunshine State. “As a stone dropped into a pool sends waves rippling to the edges,” wrote the editor of the Fort Myers News-Press, “so the impact of Project Apollo will be felt by all of Florida.”

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program